July 2009

Monthly Archive

Mon 20 Jul 2009

Overnight, Tuesday, July 21 to Wednesday, July 22 —

8:00 PM Footsteps in the Fog (1955)

An ambitious housemaid learns her employer murdered his wife. Cast: Stewart Granger, Jean Simmons, Bill Travers. Dir: Arthur Lubin. C-90 mins, TV-G, Letterbox Format

9:45 PM Secret Partner, The (1961)

A shipping tycoon with a record becomes a suspect when money goes missing from the company vault. Cast: Stewart Granger, Bernard Lee, Haya Harareet. Dir: Basil Dearden. BW-91 mins, TV-PG, Letterbox Format

11:30 PM Light Touch, The (1952)

An art thief tries to double cross his gangster boss. Cast: Stewart Granger, George Sanders, Pier Angeli. Dir: Richard Brooks. BW-93 mins, TV-G, CC

1:15 AM Whole Truth, The (1958)

A woman tries to prove her cheating husband didn’t murder his mistress. Cast: Stewart Granger, Donna Reed, George Sanders. Dir: Dan Cohen, John Guillerman. BW-84 mins, TV-PG

2:45 AM Secret Invasion, The (1964)

Five criminals win early pardons to infiltrate a Nazi outpost. Cast: Stewart Granger, Raf Vallone, Mickey Rooney. Dir: Roger Corman. C-95 mins, TV-PG, Letterbox Format

All day Wednesday, July 22 —

11:15 AM Saint In New York, The (1938)

The Saint goes undercover to get the goods on New York’s mob kingpins. Cast: Louis Hayward, Kay Sutton, Jonathan Hale. Dir: Ben Holmes. BW-72 mins, TV-G

12:30 PM Saint Strikes Back, The (1939)

The Saint helps a young beauty take vengeance on the mobsters who ruined her father. Cast: George Sanders, Wendy Barrie, Barry Fitzgerald. Dir: John Farrow. BW-64 mins, TV-G

1:45 PM Saint In London, The (1939)

The Saint’s investigation of a counterfeiting ring uncovers a nest of spies. Cast: George Sanders, David Burns, Sally Gray. Dir: John Paddy Carstairs. BW-72 mins, TV-G, CC

3:00 PM Saint’s Double Trouble, The (1940)

Reformed jewel thief Simon Templer lands in hot water when a look-alike smuggles stolen goods out of Egypt. Cast: George Sanders, Jonathan Hale, Bela Lugosi. Dir: Jack Hively. BW-67 mins, TV-G, CC

4:15 PM Saint Takes Over, The (1940)

Reformed jewel thief Simon Templar tries to help a police inspector who’s been framed on bribery charges. Cast: George Sanders, Jonathan Hale, Wendy Barrie. Dir: Jack Hively. BW-70 mins, TV-G, CC

5:30 PM Saint In Palm Springs, The (1941)

Reformed jewel thief Simon Templar’s efforts to deliver a fortune in rare stamps are complicated by murder. Cast: George Sanders, Wendy Barrie, Jonathan Hale. Dir: Jack Hively. BW-66 mins, TV-G

6:45 PM Saint Meets The Tiger, The (1943)

The Saint infiltrates a small English village run by smugglers. Cast: Hugh Sinclair, Jean Gillie, Clifford Evans. Dir: Paul L. Stein. BW-69 mins, TV-G

[UPDATE] 07-22-09. The best laid plans and all that. Our cable, Internet and phone service all took short vacations this evening and early morning. The cable came back after only a 15 minute recess, but it still means there’s going to be a big, unfillable hole in The Light Touch. I haven’t seen any of these Stewart Granger films, so the loss of any of them qualifies as at least a minor catastrophe. Hopefully it’s going to be only the one.

As for later today, I must have seen all but one or two of the Saint movies, and I probably have permanent copies of them all, but I’ll record them anyway, just in case I don’t.

Mon 20 Jul 2009

A MOVIE REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

THE MAN FROM GALVESTON. Warner Brothers, 1963. Jeffrey Hunter, Preston Foster, James Coburn, Joanna Moore, Edward Andrews, Kevin Hagen, Ed Nelson, Karl Swenson. Screenplay: Dean Riesner, Michael S. Zagor. Director: William Conrad.

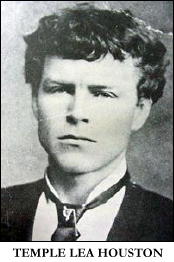

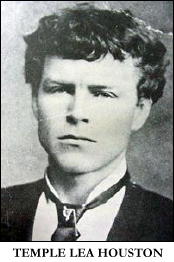

The Man From Galveston features one of the most famous figures of the old west that no one has ever heard of, Temple Houston, the last born son of legendary statesman and adventurer Sam Houston.

Although the character played in the film is called Timothy Higgins, this was the pilot for the television series Temple Houston, and released theatrically because it proved too good for television.

In the film Higgins (Jeffrey Hunter) is a colorful circuit riding lawyer who takes the case of “soiled woman,” Rita Dillard (Joanna Moore) on trial for her life for murder and as much on trial for her lifestyle as the crime.

Higgins has to not only defend his client, but also solve the murder and change the mind of a jury who would as soon hang her for her life choices as her crimes.

Preston Foster is the judge, and Grace Lee Whitney a madam (more or less, this was originally made for television).

The film is a well done short mystery (57 minutes, intended for a ninety minute television slot) loosely based on one of the real life Temple Houston’s most famous cases in which he delivered the “soiled dove defense”, still considered by many legal authorities to be the perfect closing argument. (You can follow the Wikipedia link for Temple Lea Houston to “the soiled dove defense” and read it for yourself.)

Coburn distinguishes himself in the film, and Hunter is surprisingly relaxed and comfortable playing the flamboyant Higgins (Houston), a man who is part Perry Mason and part Paladin from Have Gun Will Travel (this was not television’s first western lawyer — Peter Breck played a gunslinging lawyer in Black Saddle). The mystery is both fair and fairly revealed.

But it is the Temple Houston connection that is the true lure here. The son of the famed Texas patriot and governor of Tennessee and Texas, Houston was as famous for his fast gun as his legal expertise. (In his most famous gun duel he killed one of the brothers of outlaw and later actor and producer Al Jennings.)

He was known both for his flamboyant manner of dress (inherited from his father who died when he was only three) and his quick wit: “Your honor, the prosecutor is the only man I know who can strut while he is sitting down.”

In one of his most famous cases he was appointed by a judge to defend a man accused as a horse thief. Told to give his best legal advice, Houston was set in a room alone with his client. When the law returned the window was open and the defendant was gone. “I gave him my best legal advice,” Houston is said to have claimed.

The real Temple Houston died fairly young at age forty five. His biography, Temple Houston, Lawyer With a Gun, is by Glenn Shirley.

But Houston is best remembered by a name other than his own. Edna Ferber’s novel of the opening of Oklahoma, Cimarron features as its hero a flamboyant gunfighter, newspaper editor, lawyer, and adventurer Yancy Cravatt, based on Temple Houston.

The part was played by Richard Dix in the Oscar winning first film of Cimarron and by Glenn Ford in the remake. Both films feature the famed “soiled dove” case as a dramatic high point.

Incidentally, the twelve man jury found Houston’s client innocent of all charges, and when he died the largest selection of flowers at his grave were sent by her.

The short-lived television series that followed this pilot never really jelled and could not make up its mind if it was a mystery, trial series, or comedy. It regularly teamed Hunter with Jack Elam and lasted only one season.

But The Man From Galveston shows what might have been, a sort of frontier Perry Mason crossed with standard gun-fighting tale. Certainly Houston was colorful and unusual enough to have carried such a series, and even here in the guise of Timothy Higgins his personality shows through.

Note: Some information in this article is taken from the Wikipedia entry on Temple Houston and the Glenn Shirley biography.

Editorial Comment: From the photos of each that I was able to add to David’s review, I’d say that Jeffrey Hunter was a very good choice for portraying the real Temple Houston.

Sun 19 Jul 2009

LORD EDGWARE DIES. TV movie/episode of Agatha Christie: Poirot (ITV, A&E).. First shown in the UK on 19 February 2000 [Season 7, Episode 2]. David Suchet (Poirot), Hugh Fraser (Captain Hastings), Philip Jackson (Inspector Japp), Pauline Moran (Miss Lemon), with Helen Grace, John Castle, Fiona Allen, Dominic Guard, Deborah Cornelius, Hannah Yelland, Tim Steed. Based on the novel by Agatha Christie (US title: Thirteen at Dinner). Dramatization: Anthony Horowitz; director: Brian Farnham.

In the comments that follow Geoff Bradley’s review of Toward Zero, David Vineyard and others, including myself, have been discussing the viability of movie and TV adaptations, as compared to the original books upon which they’re based.

Which of course brought to mind (mine, that is) my disappointment in the preceding entry in this series of Hercule Poirot dramatizations, that being The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, which I reviewed here quite some time ago.

Regarding the latter, allow me to quote my slightly younger self: “I certainly did not recognize the shootout in the chemical factory between the killer on one side at the end, and Poirot and Inspector Japp (Philip Jackson) on the other. Good grief. What were they thinking?”

With Lord Edgware Dies, however, they writer, producer and director get another chance to do it right, and except for one or two details, as far as I could tell, they did. I’ve read all of the comments on IMBD, and they all agree. This was an almost perfect reproduction of the book.

In which the wife of Lord Edgware hires Poirot to intercede on her behalf in terms of his agreeing to grant her a divorce. Even though the good man (who is not, otherwise why are there so many possible suspects?) says he’s willing, he’s found dead later the same evening.

The primary suspect is Poirot’s client, played most wonderfully by Helen Grace — she’s supposed to be a woman who attracts men to her like that other Helen, the one from Troy — and she does.

The problem is, she has an alibi, an unshakable one, such as being at a dinner party set for thirteen at exactly the same time the murder takes place. And what’s more, a well-dressed look-alike is seen entering the dead man’s home just before he died.

She’s been framed, and it’s up to Poirot, with a little help from Hastings and Japp, not to mention his long-time secretary, Miss Lemon to sort through the evidence, which insists on piling up, and picking the correct killer out of the long list of possibilities.

Beautifully, beautifully done. Not perfectly done, though. There are some flaws in the story line that won’t come to mind immediately, but they may later. I knew who the killer was early on, but I confess I had my doubts when so many creatively manufactured red herrings did their best to tempt me off the trail.

Books and books, and movies are movies, and the existence of one does not negate the existence of the other. And sometimes the twain do meet. What this filmed episode of Lord Edgeware does do is to show that it can be done with fidelity to the original, that liberties do not have to be taken, and that the end result can also be as delightful and entertaining as the original.

As for Roger Ackroyd, if you’ve read the book, you know what the problems are in terms of converting it to cinematic form. It wouldn’t be easy. But the gunfight in a chemical plant? No way.

Sun 19 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

IT’S ABOUT CRIME

by Marvin Lachman

PATRICK QUENTIN – A Puzzle for Fools.

Simon & Schuster, US, hardcover, 1936. Victor Gollancz, UK, hc, 1936. Paperback reprints include: Pocket #83, 1940, with several later printings; Dell D192, Great Mystery Library #4, 1957; Ballantine F461, 1963; Avon PN238, 1969, with at least one later printing. Trade paperback: Penguin Classic Crime, 1986.

During the nineteen-thirties many movie comedies had the hero and heroine meet “cute.” Example: Claudette Colbert and Gary Cooper meeting in a haberdashery; he only wants pajama bottoms, and she only wants pajama tops. They agree to buy a single pair.

Patrick Quentin’s A Puzzle for Fools is in that tradition, as Peter Duluth, an alcoholic theatrical producer, and Iris Pattison, a young woman suffering from melancholia, met at an exclusive mental sanatorium. This book has seldom been out of print since it was first published more than fifty years ago.

The Duluth books were to get better as time went on. This book, the first which Hugh C. Wheeler and Richard Wilson Webb wrote as Patrick Quentin, is lively and readable but shows some of the earmarks of inexperience (Wheeler was only twenty-four at the time) and hasty writing; the team was very prolific in the years before World War II.

Duluth’s fears as he goes through alcohol withdrawal while trying to solve a murder are not well conveyed. Instead, we have him saying things like, “Those were some of the most harrowing moments of my life,” but the authors do not make the readers feel it.

Too often the authors rely on Had-I-But-Known writing to get across that there are sinister events to come. For example: “Of course, I had no idea then of the fantastic and horrible things which were soon to happen in Doctor Lenz’s sanatorium. I had no means of telling just how significant these minor and seemingly pointless disturbances were.”

And, later, “Maybe I could have prevented a lot of tragedy if I had gone to the authorities there and then.” (Quentin comes close to setting a world’s record for the amount of information withheld from the police in this book.)

The pace is very quick, and Duluth’s light, self-deprecating tone makes him an enjoyable narrator. Don’t expect the kind of sophistication to be found in the British puzzles of the nineteen-thirties, though Wheeler and Webb were born in England.

No American writer has quite achieved what is to be found in Allingham, Innes, Blake, Sayers, et al. There must be an invisible barrier on the western shore of the Atlantic.

Incidentally, if the name Hugh Wheeler sounds familiar, it should. After he stopped writing mysteries in 1965 he became a major playwright, best known for his collaborations with Stephen Sondheim on such works as A Little Night Music, Pacific Overtures, and Sweeney Todd.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 2, March/April 1987.

Editorial Comment: This is the second of two mysteries taking place in psychiatric institutions that Marv referred to in his recent review of A Mind to Murder, by P. D. James. Although the book was in print in 1987, it no longer seems to be, some 22 years later.

Coming Soon: Another review of this book by Newell Dunlap and Marcia Muller, taken from 1001 Midnights; then my review of Puzzle for Players, the second book in the series.

Also relevant: Kevin Killian’s review of The Crippled Muse (1951), by Hugh Wheeler; and two of my previously posted reviews. First, Death My Darling Daughters, by Jonathan Stagge; then Return to the Scene, by Q. Patrick.

Sun 19 Jul 2009

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

AGATHA CHRISTIE’S MARPLE: TOWARD ZERO. ITV. Series 3, Episode 3. First telecast in the UK on 03 August 2008. Geraldine McEwan, Julian Sands, Paul Nicholls, Greg Wise, Saffron Burrows, Julie Graham, Tom Baker, Eileen Atkins. Based on the novel by Agatha Christie. Director: David Grindley (uncredited).

Agatha Christie’s Marple which is what it was called in the listings, returned with the penultimate outing for Geraldine McEwen in the eponymous role. It was an adaptation of Towards Zero, a Christie novel in which Miss Marple plays no part.

Here she was interjected into the otherwise fairly faithful plot (if my faltering memory of reading it some twenty odd years ago plus the vague plot descriptions in a couple of reference books can be relied upon), involving a gathering of people at the home of Lady Tressilian — played by Eileen Atkins in a fairly star-studded cast which included Tom Baker (former Dr Who and Sherlock Holmes), Saffron Burrows (of Boston Legal) and Alan Davies (Jonathan Creek).

I have been critical of previous outings in this series but I enjoyed this one. The post-WWII settings were superb, and I thought McEwen kept the knowing grins down to at least a reasonable proportion. There was an amusing gaffe when a scene showing the protagonist Neville Strange (Greg Wise), a tennis player, at Wimbledon (incidentally his opponent was played by Greg Rusedski), had the scores shown on an electronic scoreboard.

Sat 18 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

E. C. R. LORAC – I Could Murder Her.

Doubleday Crime Club, US, hardcover, 1951. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, April 1952. Paperback reprint: Popular Library, no date [ca. 1960]. Originally published in the UK by Collins Crime Club, 1951, as Murder of a Martinet.

Muriel Farrington is a domineering woman who, unfortunately for them, has her entire family living with her in her stately home. She tries, often successfully, to run the lives of her children, her stepchildren, her in-laws, and her husband, and she seems to be despised by all except her husband and one son.

When she is found dead one morning in her bed, the family doctor, who is old, ill, and hasn’t been very able for years, is unable to attend and bestow a certificate, which he would have done without investigation or thought.

A younger, more able and perceptive doctor has to be called in, to the shock of whoever the murderer was, and he does not find the death natural.

A hypodermic puncture in her arm leads him to believe, correctly as it turns out, that someone has injected insulin into the woman. Since she was not suffering from diabetes, death was the inevitable result.

The characterizations of those in the household are well done, particularly the one of Mrs. Pinks, the charwoman. The motives of each of the family members who may have killed Muriel Farrington are set forth clearly.

The investigator, Chief Inspector Macdonald of the C.I.D., a continuing character in many of Lorac’s novels, is not very distinct, however. He is quiet, kind, considerate, and an excellent investigator in his own way, but that’s all that is learned about him.

Perhaps Lorac had delineated Macdonald in his earlier cases. Nonetheless, she could have taken a little more effort here to acquaint new readers with him.

A fairish-play novel. The murderer was evident to me, and I don’t spot too many. The clues are psychological rather than physical.

– From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 9, No. 3, May/June 1987.

Sat 18 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[27] Comments

CAROLYN WELLS – The Wooden Indian. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, US, 1935.

A recent replacement of a hot water heater in our basement necessitated the moving of several boxes of books in order in order to make room for the old one to be dragged out and the new one brought in. This brought to the light of day (figuratively speaking) several shelves of other books that I was glad to lay my eyes on again. It had been six or seven years, at least.

I am talking several hundred books in total — being moved and/or coming to light again — and of these, I picked one to read, not realizing at the time that Bill Pronzini had beaten me to it. One of his reviews from 1001 Midnights is of this same book and was posted here on this blog back in January of this year.

This is a Fleming Stone mystery, and while Bill called him “colorless and one-dimensional,” I’d say he’s a step or two above that in both categories, but on the other hand, he’s certainly no more than that.

Dead is a man whose demise is so certain, and at the hand of another, that Bob Barnaby, a friend of Stone’s staying in the same elite area in Connecticut (near the Pequot Club Grounds, a center of the book’s activities), senses it too, and calls him in on the case long before the murder actually happens.

It seems that David Corbin, a noted stamp collector as well as that of Indian memorabilia, is rather a bully to his wife, in public, at least, and his wife is also one of those beauties who suffers in silence while attracting other men to her like, well, moths to a flame.

The murder weapon is an arrow, fired from the bow of, well, guess what, a wooden Indian in full regalia in the dead man’s study. There is limited access to the room, but I do not believe that the mystery could really be called one of the locked room variety.

I’d expected the story to be stodgy and formal, but I was in error in that regard. The banter is generally witty, although of the upper crust type– no dark and dirty streets here — and the tale is heavy on dialogue, so much so that one must stop every once in a while and trace the paragraph back to rediscover who it is that’s talking.

This is also one of those books in which all of the suspects are gathered together in one room for a final confrontation, whether it’s necessary or not. Stone claims not to have known who the killer was until the very last moment, but an even less than astute reader should know from the questions he’s been asking who it is that he suspects long before then.

As a detective story, then, The Wooden Indian lands solidly in the “mediocre” category. Enjoyable enough, but distinctly below par. Bill concludes his comments about Carolyn Wells’ detective stories in general by saying, “… the casual reader looking for entertaining, well-written, believable mysteries would do well to look elsewhere.”

While I’m far from discouraged enough to say I’ll never read another one of her books, I’d have to say that I’m not especially encouraged to do so either — not immediately, at any rate.

Sat 18 Jul 2009

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

TWILIGHT WOMEN. Independent Film Distributors / Lippert, 1952. Originally released in the UK as Women of Twilight. René Ray, Lois Maxwell, Freda Jackson, Vida Hope, Joan Dowling, Laurence Harvey. Screenplay by Anatole de Grunwald, based on a play by Sylvia Rayman. Director: Gordon Parry.

On the Obscure Movie front, several years ago I encountered an unintentionally bizarre little item called Twilight Women, made in Great Britain back in 1952. The word “twilight” had a specific connotation in sleazy paperbacks of those days, but the Twilight Women of this film all happen to be unwed mothers.

Hard to believe now, but fifty years ago, Unwed Motherhood was a brand of shame roughly equivalent to a criminal record. In fact, the home for single-parents-to-be in Twilight Women is not unlike a prison at all, with its corrupt warden/landlady, her venal and sub-normal hench-persons, and the assorted tough gals, tramps and frightened innocents stuck in her care.

Their stories play out with surprising intelligence and compassion, however (the adaptation of Sylvia Raymond’s play being done by Anatole de Grunewald, who was rather good at it) and while the film never tries for explicit social commentary, its depiction of women made victims of society’s moral code leaves little doubt of whom we should root for.

This is, however, no message picture; it’s far too weird for that. For one thing, the print I saw had an odd blue tint to it, giving it the appearance of a Guy Madden film. For another, there’s a sort of introduction, in which the faces of the ladies morph eerily into one another.

And strangest of all is the fleeting presence of Laurence Harvey, early in his career, playing some sort of lounge lizard. The sight (and sound) of this patently-hateful actor charming the ladies and belting out love songs in an obviously-dubbed baritone must be seen to be disbelieved.

Or perhaps you shouldn’t. I still hear him sometimes, in the long dark nights of the soul…

Editorial comment: We all know who Lois Maxwell is, I’m sure. She’s one of the young mothers in Twilight Women, while René Ray, whose photo you see below, plays another, she being gangster moll Viv Bruce — the gangster being Jerry Nolan, the low-life club singer played by Laurence Harvey, whose role in the film was pointed out so perceptively by Dan. (I am not positive, but I believe it is also René Ray’s photo on the DVD cover above.)

Sat 18 Jul 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

A REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

ERIC HEATH – Murder in the Museum. Hillman-Curl Clue Club Mystery, hardcover, 1939. Mystery Novel of the Month, digest-sized paperback, unnumbered, 1940.

Readers of Bill Pronzini’s book Gun in Cheek and Son of Gun in Cheek will recall Eric Heath, author of the breathless classic, Murder of a Mystery Writer (1955), wherein the hero, Dr. Wade Anthony, propounds the “motion picture theory of crime solving.” The doctor’s secretary-assistant was one Penny Lake.

(The latter was previously reviewed here. The book was a rewrite of Heath’s own Death Takes a Dive (1938), the protagonists of which were Copey Clift and Winnie Preston. Forgive the interruption. Please continue reading.)

There is nothing quite that wonderful in Murder in The Museum, but rest assured, in all other ways it is as alternative as alternative gets. And more fun for it.

Museum also features that attractive sleuth Cornelius (Copey) Clift Jr., America’s outstanding criminologist; and his bride-to-be, Watson, and narrator of our little adventure, Winnie Preston, who conveniently is also Copey’s secretary.

As the novel opens they are driving up the coast from San Francisco to Seattle where they are to be married in the home of Copey’s wealthy mother when they stop to visit Copey’s old friend Alexander Cameron, a millionaire obsessed with Egypt, and prone to eccentricities — not the least of which being his sultry and seductive French dancer wife Sidi, but Winnie isn’t worried, “because the average man does not want to marry that sort of woman.”

And they are hardly settled in before they catch her performing a strange dance nearly nude around an Egyptian sarcophagus that belongs to her husband’s collection. You know how foreigners are.

Things start popping soon after, when their host is found murdered in the strange triangular shaped museum attached to the house — locked in with no way out in a secret room, unmarked save for a small puncture wound on his jugular vein.

“You know Winnie, I think were up against an enigma here. It looks as though our trip to Seattle is delayed …”

“We are together,” was all I said …

“Swell guy…”

And we’re off. Pretty soon Copey and Winnie uncover a crystal coffin with a perfectly preserved corpse of a beautiful Egyptian girl, and the suspects grow:

Cameron’s adult son Dennis with whom he quarreled; Seilimann, his loyal butler; the French wife; Haroud, the curator of the museum; and Mannheim, who believes Cameron cheated him out of an ornate scarab ring found on the dead man’s finger.

Captain Forquer of the police arrives and of course bows to Copey’s superior knowledge as any good policeman would… But Winnie is concerned:

“Don’t laugh at me Copey, but I think there is something connected with the supernatural tied in with this affair.”

Of course Winnie is just being silly, as Copey will prove, despite Cameron’s belief that his wife Sidi and he had been lovers in a previous life. Still, Winnie is a bit prone to melodrama for the wife to be of a criminologist.

My mind drifted to moving pictures I had seen — murder mysteries. In nearly all of them there had been some element of comedy, some lightening touch. But of course they were based on pure fiction. In this real-life situation, it seemed that every moment I had been in this house had been wrapped in an atmosphere charged with electricity, and that any moment an explosion would occur, obliterating us all.

We can only hope, but instead we get a heavy fog — other than the one Winnie seems to be in perpetually.

And you can’t really blame her when the body in the crystal coffin turns out to be Zuleyka, Cameron’s lost reincarnated love.

Of course Copey brings it all to a solution after a bit of business on a boat and a storm and a missing body, and Heath pulls off a unique twist — the most likely suspect is guilty.

Copey, borrowing a note from Philo Vance’s notebook, allows the suspect to commit suicide (“I detest executions…”) and he and Winnie are once again on their way to Seattle.

“Right,” said Copey, “And now I just want to say two words before you shut your eyes and go to sleep.”

“What are they, Copey?”

“Swell guy.”

It’s a wonder there isn’t another murder.

Editorial Comments: It is I who added that parenthetical second paragraph to David’s review above. Following the link will give you more information about Murder of a Mystery Writer than you may want to know, along with a complete bibliography for Eric Heath, the author.

For a complete gallery of the covers of the books in Hillman-Curl’s Clue Club series, you need go no further than this page from Bill Deeck’s Murder at 3 Cents a Day website.

Fri 17 Jul 2009

REVIEWED BY TED FITZGERALD:

BRENNER. TV series. CBS-TV, 1959-61-64. Ed Binns, James Broderick, with Dick O’Neill, Walter Greaza, Sydney Pollack, Gene Hackman. Executive producer: Herbert Brodkin. Various screenwriters & directors.

Brenner was one of those overlooked gems of the black-and-white TV era, a half-hour character-driven drama about two New York City cops, Roy Brenner (Edward Binns) a veteran member of The Confidential Squad (aka Internal Affairs), and his son Ernie (James Broderick), a rookie detective.

The focus was police corruption and the emotional cost of police work, themes explored at greater length and intensity by such later shows as Naked City and Police Story.

Brenner utilized a low-key approach, though, and it pays off. It doesn’t utilize the city as a character the way Naked City did, but its exteriors capture the time (1959) and place and Manhattan mood just as well.

A big help is the supporting cast of then mostly unfamiliar New York actors, including Simon Oakland, George Grizzard, Michael Strong, Frank Sutton, Frank Overton and an unbilled Gene Hackman, who pops up several times as a patrolman.

The recent DVD box set from Timeless Media features 15 of the 25 or 26 episodes produced. (See below.)

The visual quality on most of the episodes is outstanding. I’d seen a couple of episodes years ago and always hoped I’d get to see more. I was not disappointed.

NOTE: The series was first televised in 1959 (6 June to 19 September) and appeared in re-runs on CBS during the summmers of 1961, 1962, and 1964, with two new episodes appearing in 1961. In the fall of 1964 (17 May to 19 July) a summer season of several new episodes appeared. According to the The Classic TV Archive, the total number of episodes that actually aired is considered to be 25.

« Previous Page — Next Page »