September 2009

Monthly Archive

Sat 26 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[11] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

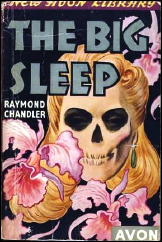

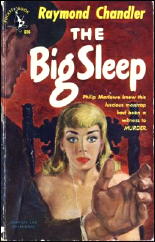

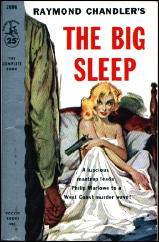

RAYMOND CHANDLER – The Big Sleep. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1939. Reprinted many times, in both hardcover and paperback, including Avon Murder Mystery Monthly #7, 1942; New Avon Library 38, 1943; Pocket 696, 1950; Pocket 2696, 4th printing, 1958.

Film: Warner Bros., 1946 (Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall; scw: William Faulkner, Leigh Brackett, Jules Furthman; dir: Howard Hawks). Also: United Artists, 1978 (Robert Mitchum, Sarah Miles; scw & dir: Michael Winner).

Speaking of Film Adaptations of Classic Mysteries, Howard Hawks used to reminisce to interviewers about the scene in a book shop in The Big Sleep (Warner Bros., 1946) to the effect of: “I said to Bogart, ‘This scene is awfully ordinary; can’t we do something to liven it up?’ and he put on a pair of glasses and started lisping and camping it up, and it was funny, so I said, ‘Great! Let’s go with that.'”

Which is a good story, except that the passage in Chandler’s novel is written just like that: glasses, obnoxious effeminacy and all. Granted, the scene in Chandler’s book isn’t as funny as the one in Hawks’ movie, but ’tis there and ’twill serve.

The Big Sleep (Knopf, 1939) was another book I read in High School, but I reread it my senior year in College, and I revisit it every ten years or so since then, always finding something fresh and readable to make me glad I came back. The plot is a mess, and the quality of Chandler’s prose is sometimes strained when it should drop like the gentle rain from heaven on the place beneath, but when it works well, there’s nothing like it, and Sleep brings a colorful cast of bit players to pulp-life with energy delightful to behold.

Again, there’s room to carp. Chandler’s handling of gay characters is hysterically unsympathetic (“… I took plenty of the punch. It was meant to be a hard one, but a pansy has no iron in his bones whatever he looks like.”) and describing an over-decorated house, Marlowe says it “…had the stealthy nastiness of a fag party.” Well how would he know?

And again, that’s just carping about a classic. The Big Sleep works on several levels, and offers some happy surprises along the way. I particularly liked the passage cataloguing the detritus of a shabby office building where Marlowe notes, “against a scribbled wall a pouch of ringed rubber had fallen and not been disturbed.”

Nowadays of course, a writer would just say “used condom” and be done with it, but Chandler’s coy self-censorship offers the kind of unique charm that seems lately to have gone the way of all flesh.

Damn. Two references to Shakespeare and one to Samuel Butler in a single review of The Big Sleep; that’s gotta set some record for pretentiousness.

Sat 26 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

THREE REVIEWS BY FRANCIS M. NEVINS, JR:

DOUGLAS CLARK – Deadly Pattern. Cassell, UK, hardcover, 1970; Stein & Day, US, hc, 1970.

In this plodding and drearily written quasi-procedural, the slightly snobbish Detective Chief Inspector George Masters and his three Scotland Yard subordinates are dispatched to a tiny English coastal town to investigate the almost simultaneous disappearances of five drab middle-class women.

When four of them are found buried by the seashore, Masters and company crawl into action, taking 169 pages to uncover a psychotic killer who should be apparent to every reader by page 30. A few deft touches of character and description don’t save this mediocre tale.

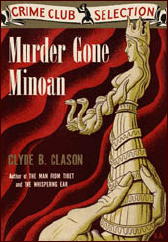

CLYDE B. CLASON – Murder Gone Minoan. Doubleday Crime Club, 1939. Hardcover reprint: Sun Dial Press, 1940. Rue Morgue Press; trade paperback, 2003. UK title: Clue to the Labyrinth, Heinemann, hc, 1939.

This one takes place on a private island off the California coast, owned by a Greek-American department store tycoon with a passion for the ancient Cretan civilization — an ideal setting for an investigation by Theocritus Lucius Westborough, professor of classics and amateur of crime.

When a priceless Minoan religious image disappears from the tycoon’s Knossos-like palace, Westborough is asked to take the case and soon encounters a mess of amorous intrigues and two murders apparently committed by a worshipper of the snake goddess of Crete.

The unusual setting justifies Clason’s abundance of classical allusions, and the sections of the story he tells in transcript and document form are neatly handled, but the plot turns out to be a routine matter of professional criminality and Westborough’s solution is hopelessly unfair to the reader. A morass of needless adjectives and circumlocutions for “he said” clutter up the ersatz-classical style beyond endurance.

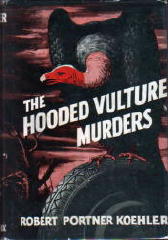

ROBERT PORTNER KOEHLER – The Hooded Vulture Murders. Phoenix Press, hardcover 1947.

Our heroes are two hapless California private eyes who stumble upon the murder of a blackmailing journalist while driving through southern Mexico on the uncompleted Pan American Highway.

Naturally the bumbling native officials welcome with open arms the intrusion of two brilliant Anglo sleuths into the case, although the readers may wish the boys had stayed home.

Koehler paints local color vividly, but his novel is ineptly plotted, woefully written, pathetically characterized, laughably clued, and all in all a pretty lame excuse for a detective story.

– These three reviews appeared earlier together in the

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 3, No. 3, May-June 1979.

Editorial Comment: An earlier review of the Clason book can be found here on this blog, a mere 200 posts ago.

Fri 25 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

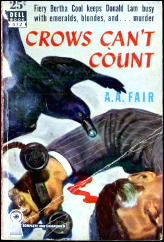

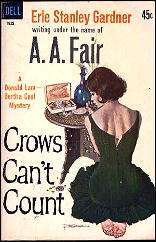

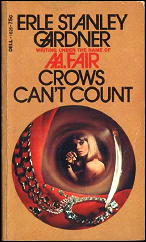

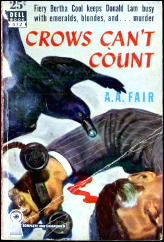

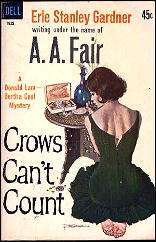

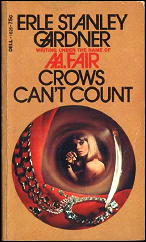

ERLE STANLEY GARDNER writing as A. A. FAIR – Crows Can’t Count.

William Morrow, hardcover, 1946. Paperback reprints include: Dell 472, mapback edition, 1950; Dell D373, McGinnis cover art, September 1960; Dell 1625, September 1972 (all shown).

Not one of the better books in the series of cases solved by the well-known amusing pair of private eye detective partners, Donald Lam and Bertha Cool, I wish I didn’t have to say. Bertha Cool is the humorous one, although she doesn’t intend to be, but in terms of figuring out who a killer is, she’s shrewd enough when it comes to money, but otherwise she’s not the brighter one of the pair.

No, that’s Donald Lam, who tells all of the stories, but he tells them so close to the vest that if a reader ever tried to figure out what he’s thinking and why, it would be like climbing a wet noodle fastened to a sky hook on the other end – the imaginary kind — and greased all the way up with the finest grade of cooking oil.

This one has something to do with emeralds, and a trust fund with two trustees and two beneficiaries, one male and one female, the latter of whom is very good looking and calls one of the trustees Uncle Harry but kisses him as though he weren’t a relative, which he isn’t, I don’t think. Donald Lam also gets in the way of the lady’s kisses too, so it isn’t as if she were playing favorites.

There is also something to do with a crow, and as crows tend to do, this one is attracted to bright shiny objects. This particular one, as the title also suggests, is not very good at math. But crows do what they do, and what they do makes sense, even to non-crows.

But I could not, while reading this book, figure out why the characters in it did such incomprehensible things, not including Donald Lam as one the characters, but since his reaction to such strange behavior was so minimal, I shrugged my shoulders (figuratively) and said that the author, Mr. Gardner, must have had a bad few weeks when he was working this one up.

Turns out, ha-ha on me, that the incomprehensible behavior (as far as I was concerned) was what tipped Donald Lam as to (eventually) what kind of scheme was going on. Here’s where Lam not having a Watson comes in. Bertha’s as much in the dark as to what was going on as I was, but at least I didn’t stand there sputtering and saying “Fry me for an oyster.”

I think in detective stories there should be some discussion going on between the would-be solvers of the mystery, to consider this possibility and then that, bringing up red herrings and false trails to make the tale more complicated with an wide array of suspects, means, and motives — and puzzling over them. Lam talks to no one in this book, and by the time he headed off to Columbia, the South American country, I’d given up on figuring out the case on my own as a lost cause.

That Bertha also ends up in Columbia is where a lot of the humor I mentioned above comes in. It’s hot, she doesn’t speak Spanish, and she’s been sold a bill of goods that would have been totally unnecessary if Lam had told what little he knew or guessed or had a hunch as to what was going on.

The case is essentially solved when on page 188 a giovernment offical for the country of Columbia named Ramon Jurado snaps his fingers, which he follows up on page 196 when he sends Lam a telegram consisting of a name and address, to which Lam goes and proceeds to the apartment of one of the players in the story to tell her exactly what had happened and when. That it takes 10 pages of small print to tell her tells you something about how complicated this story was, and it’s still not over – there is something like 15 more pages of explanation to go – but how on earth Lam did know all of this?

Other than what I’ve said so far, I have no idea.

Fri 25 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY GEOFF BRADLEY:

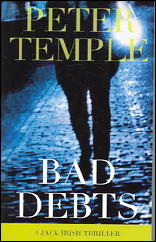

PETER TEMPLE – Bad Debts. Collins, Australia, pb, 1996. MacAdam/Cage, US, hc, 2005. Quercus, UK, pb, 2007.

I read this author’s 2005 novel, The Broken Shore, which I enjoyed, even though I thought it had a few flaws and it probably wouldn’t have been my choice for an award. (I don’t know what would have been as I don’t read many newly published books.)

[The Broken Shore was awarded the Duncan Lawrie Dagger (formerly the CWA Gold Dagger for Fiction) for 2007. Temple, born in South Africa, is the first Australian to win the award.]

Temple previously wrote a four book series about a Melbourne private eye named Jack Irish, and this is the first in that series. Jack, who is the narrator, comes with many of the usual troubles.

He had been a lawyer with a successful practice, but after a client had killed his (Irish’s) wife in revenge, Irish had become a drunk before straightening out a little. Now he does a little minor legal work but mainly works as an investigator for his old legal partner.

Here he is approached by an old client who is out from jail, having been convicted on a hit-and-run death while he was drunk. Before Irish can follow up, the man is dead, shot in a police ambush. Irish has to re-investigate the case from ten years before when he had been going through the motions after his wife’s death. The investigation leads to a conspiracy on a governmental stage and soon he is the target of ruthless killers.

On the whole, this was a readable book, though it dragged a little in places; and the plot twisted and turned, though in not wholly unexpected ways. I’m not sure I would classify this as absolutely top-notch but it was not bad. If the second book in the series falls into my hands, I might well give it a try.

PETER TEMPLE – Bibliography:

Bad Debts (1996). [Jack Irish]

An Iron Rose (1998)

Shooting Star (1999)

Black Tide (1999). [Jack Irish]

Dead Point (2000). [Jack Irish]

In the Evil Day (2002) aka Identity Theory.

White Dog (2003). [Jack Irish]

The Broken Shore (2006).

Truth (2008). [Book 2 in “The Broken Shore” series.]

Fri 25 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

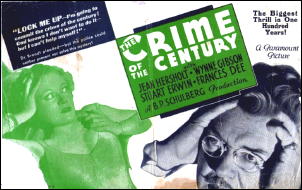

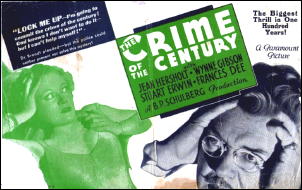

THE CRIME OF THE CENTURY. Paramount, 1933; Jean Hersholt, Wynne Gibson, Stuart Erwin, Frances Dee, Gordon Westcott, Robert Elliott, David Landau, William Janney. Screenplay adapted by Florence Ryerson from the play The Grootman Case by Walter Maria Espe Director: William Beaudine. Shown at Cinevent 41, Columbus OH, May 2009.

Jean Hersholt, a well-known “alienist,” comes to the police to beg them to arrest him. If they don’t, he is going to kill a man, one of his patients who works for a bank and whom he’s ordered while under hypnosis to bring him 100,000 dollars.

(This would appear to contradict what I have always understood about hypnosis, which is that subjects won’t obey orders that are against their basic nature. But I suppose that the doctor knows his patient better than I do.)

The cast of characters consists of an adulterous wife, a nosy reporter, two very incidental servants, a missing son, and the wife’s lover who seems to be almost everybody’s choice for the killer.

This is not one of those legendary Paramount pictures that turn out to be long unseen gems, but a stagey, hokey melodrama that not even some good actors can save. Not a bomb, but a bottom-of-the-bill filler.

Fri 25 Sep 2009

MAN IN THE VAULT. RKO Radio Pictures, 1956. William Campbell, Karen Sharpe, Anita Ekberg, Berry Kroger, Paul Fix, James Seay, Mike Mazurki, Robert Keys, Nancy Duke, Gonzalez Gonzalez, Vivianne Lloyd. Screenplay by Burt Kennedy, based on the novel The Lock and the Key by Frank Gruber. Director: Andrew V. McLaglen.

I’m willing to bet that if you recognize more than two or three of the actors and actresses in this 1950s style crime movie, you’re somebody who looks up somebody on IMBD at least once a day. Casual movie viewers will know only one, and she’s barely in the movie, so if that’s why you might ever pick out this movie to see on DVD, say, you’re going to be out of luck.

The star is William Campbell, and I’ll see if I can’t find a good photo of him. He plays a apprentice locksmith named Tony Dancer in the movie, and he’s hired by a gangster to help pull off a job for him. But getting back to Campbell, I learned a new word today:

Quiff: “Popularized mostly by 50s rockabillys, a quiff is basically a forelock that is longer than the rest of one’s hair on top, and is usually combed upwards (and back), or to the side, or made to hang over the forehead. Depending on the wearers hair type a spot of gel or grease may be in order. Very stylish & manly. If done properly.”

Campbell also looks something like Tony Curtis, and he’s had something like 80 appearances in movies and TV, the last one in 1996, and I don’t believe I’ve ever noticed him in any one of them. Whether that’s my fault or the movies he’s been in, you’d have to go to IMDB and look him up.

The movie’s in black and white, and I’ve never seen it before. All of these years I thought this was one of those grand caper movies, in which a gang of crooks works out a precisely laid out plan to rob a bank. Not so. All Tony Dancer has to do is get inside the room where the safety deposit boxes are, make a key to get into one of the boxes, return and remove the contents.

A little sweat on the brow, hoping the bank teller at the door doesn’t turn around, and there’s nothing to it. Problem is, Tony Dancer isn’t really crooked, but on the other hand he’s fallen for one of the girls (Karen Sharpe) he meets at a party thrown by the gangster (Berry Kroger), and all kind of complications ensue.

Being filmed in various parts of 1950s Los Angeles is a plus, but bad pacing and a story line that moves in fits and starts are not. It’s a good example of what it is, though, a 1950s crime film – one not particularly noirish in theme, but filmed with the same amount of money in the till to begin with – that I somehow found both appealing and entertaining.

Thu 24 Sep 2009

A COMIC BOOK REVIEW BY DAVID L. VINEYARD:

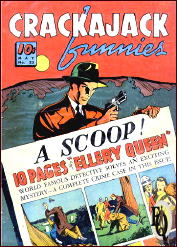

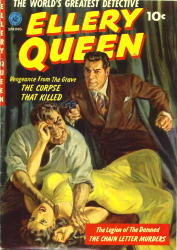

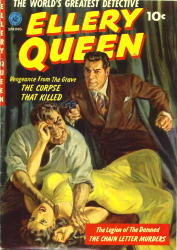

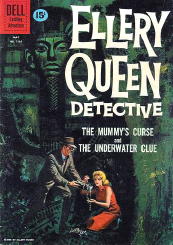

ELLERY QUEEN #1. Ziff-Davis, Spring 1952.

Crime more than mystery and detection has been a staple of comic books from the beginning. Two-fisted gumshoes and tough cops have always outnumbered the more intellectual types, but a few did manage to sneak in both in comic strip reprints and original material.

Among that small company who had multiple titles of their own over the years from multiple publishers are Sherlock Holmes, Charlie Chan, and Ellery Queen.

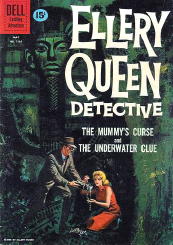

Ellery Queen may seem an odd choice for the comics, but having succeeded in every other media, there he was in Crackajack #23 (May 1940) from Dell Comics, running through issue #42 (December 1941) alongside Frank Thomas’s costumed hero, the Owl, and reprints of Tarzan, Red Ryder, Wash Tubbs, and Dan Dunn.

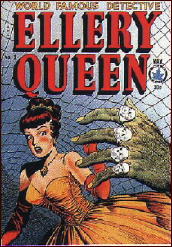

Ellery next appeared in four issues of his own title from Superior in 1949 with art from EC horror comic staple Jack Kamen and L.B. Cole, then in 1952 Ellery returned in two issues from Ziff-Davis.

In 1961 Ellery was back at Dell in Four Color Comics with art by Mike Sekowsky, a journeyman artist who also helmed Peter Gunn’s only comic book appearance and was the first artists on DC’s Justice League of America, as well as working on Wonder Woman and many other iconic characters.

But here we are concerned with the Ziff-Davis issues from 1952. Ziff-Davis aimed its titles at older kids and adults and as a result has an eclectic run of titles from staples like science fiction, horror, and westerns to oddities like Sky Pilot about a missionary in the far North, Crime Clinic about a prison psychiatrist, and Captain Fleet about the captain of a freighter. Ellery would seem a perfect fit.

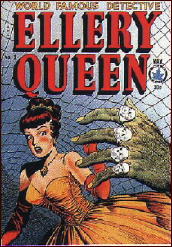

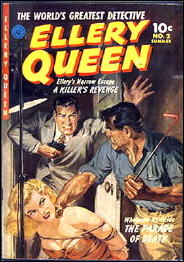

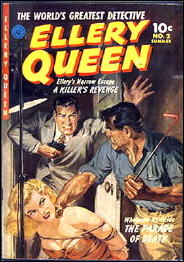

Ziff-Davis was also set apart by its garish painted covers, often by pulp and later men’s magazine favorite Norman Saunders. Both issues of Ellery Queen sport Saunders’ covers with a muscular Ellery behaving more like Mike Hammer than Ellery Queen.

Issue #2 even has a beautiful blonde being threatened by a brute with a red hot poker. Luckily the stories inside are a bit more subdued.

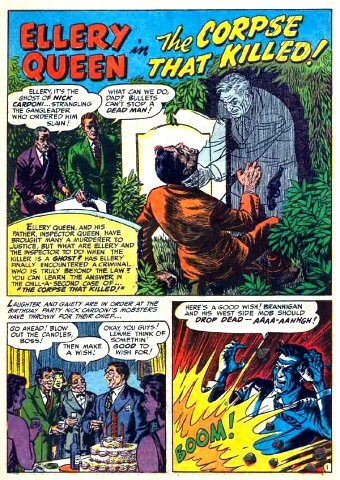

Ellery Queen #1 for some reason has Ellery looking like actor William Gargan, who replaced Ralph Bellamy in the Columbia movie series. (In issue #2, again for no reason, he looks like Bellamy, though both are by the same artist.) The book features Ellery in two stories; the first a disposable crime tale “The Corpse That Killed” that Ellery ‘solves’ by simply trailing some hoods to a cemetery. (See below.)

The second is more ambitious, and actually features some detective work on Ellery’s part in a fairly interesting mystery, “The Chain Letter Murders.”

The story opens as an elderly woman walks into an office, pulls out a gun, and kills a man. She flees, but falls in front of a bus and before she dies is overheard to say: It’s better this way.”

Inspector Queen is still baffled when Ellery shows up, and they have hardly begun to sort that one out when the new boxing champ is murdered in his shower after double crossing a gambling ring. Ellery follows damp footprints to the room of a man in the iron lung — who confesses he killed the boxer, his last statement before silence: “It’s better this way.”

But this time they find a letter in the killer’s apartment and a list of names. Ellery tracks down the next man on the list and prevents his murder, but again the would be killer only says: “It’s better this way.”

Hiding the fact he and his father intervened in time to save the next man on the list, Ellery persuades the potential victim’s wife to pretend to be grieving, and he and his Dad wait for the inevitable suspect to show up.

They follow the man to the remote Temple of Hope, home of the Mighty Eye cult and watch as the man pays an unseen figure and leaves. Now Ellery has it figured out, and pretends to attempt and fail at suicide to draw out the cult leader. It seems the man was using the cult to front a clever murder racket.

Taking advantage of people he knew were suicidal but lacked the courage to die, he enlisted them in “the Legion of the Damned,” telling them they would receive a list of others like them wanting to die, and when they killed that person they would move up on the list, their own death a little closer. Then he contracted out to people who wanted someone dead and put their name on the list for money. Send out a chain letter, and the deed was as good as done.

Alas, I don’t know who the writer and artist were, but the art is good and the story a bit closer to an actual mystery than we had any reason to hope for. There’s no challenge to the reader (there is in at least one of the Dell Four Color comics), but there is a fairly baffling mystery, and to be fair, it’s a pretty good idea — for a comic book mystery.

Okay, it wouldn’t hold up in print, but for a comic book of that period it isn’t bad, and I’ve seen and heard more preposterous plots on radio and television dramas and more than a few movies. For a comic book, it’s about as close to the real Ellery Queen as we could hope.

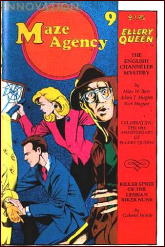

Except that we did get the real Ellery Queen once. The Maze Agency (Comico, 1989) was a comic book about a pair of private eyes, and in issue #9 the creators, long time Queen fans, got permission to have Ellery help them out in a mystery.

It’s a nice little coda to Ellery’s on-again off-again comic book career. It certainly beats Charlie Chan’s final bow in The Amazing Chan and the Chan Clan.

Anyone interested can download the two Ziff-Davis Ellery Queen’s for free at goldenagecomics.co.uk where they will also direct you to free downloads of comic book readers (cbr and cbz) that are easy to install and use. There are also issues of The Saint available and much great old stuff from the early comics that is in public domain.

Thu 24 Sep 2009

REVIEWED BY BOB SCHNEIDER:

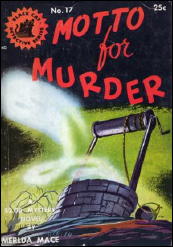

MERLDA MACE – Motto for Murder. Messner, hardcover, 1943. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition, November 1943. Digest paperback: Crestwood / Black Cat Detective #17, 1945 (abridged).

Motto for Murder was one of a trio of murder mysteries written by Merlda Mace during the 1940’s. The detective she deploys in this story is Timothy J. O’Neil better known as Tip to his friends. He is a 26 year old “special investigator” for Barnes and Gleason, a New York City investment firm.

How he got this job is one of the big mysteries of this book since he readily admits that he is not much of an investigator and his performance during the story bears this out.

This is, in essence, a country house mystery. The house is an isolated mansion located in the mountains of northern New York State near Lake Placid. The controlling and quite unpleasant matriarch of a wealthy family has gathered her extended family to tell them that she has screwed them out of their inheritances. A snowstorm descends on the region and several murders occur during a long Christmas weekend.

This seems to me like a combination of a mediocre Mignon G. Eberhart mystery and a bad Ellery Queen mystery. The author can put words and sentences and paragraphs together in a coherent manner but the book, on the whole, is a disappointment.

The physical and character clues are not first rate, and the author employs a HIBK technique that serves no valid storytelling purpose. Since the characters insisted on wandering around in the dark, leaving their bedrooms unlocked at night and napping in vulnerable spots, the killer did not have too much trouble carrying out the murders. The “mottos” from the title of the story refer to fortune-cookie type candies wrapped in little papers containing sayings which play a small part in the solution.

Merlda Mace was a pseudonym of Madeleine McCoy. Apparently “Tip” O’Neil is not a series character, but according to Al Hubin’s Revised Crime Fiction IV, Mace’s other two mysteries utilize a female sleuth called Christine Anderson (the ‘blonde’ in Blondes Don’t Cry).

Bibliographic data: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV]

MACE, MERLDA. Pseudonym of Madeleine McCoy, 1910?-1990?

Headlong for Murder (n.) Messner 1943 [Christine Anderson; Connecticut]

Motto for Murder (n.) Messner 1943 [New York]

Blondes Don’t Cry (n.) Messner 1945 [Christine Anderson; Washington, D.C.]

Wed 23 Sep 2009

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[13] Comments

Reviewed by MIKE GROST:

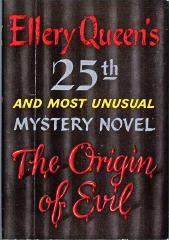

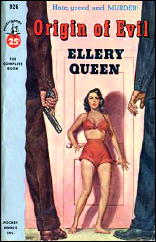

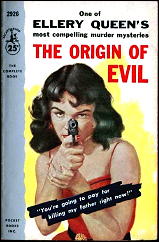

ELLERY QUEEN – The Origin of Evil. Little Brown, hardcover, 1951. Reprinted many times. Paperback editions include: Pocket 926, 1953; Pocket 2926, 3rd printing, 1956 (both shown). Signet, 1972; Perennial, 1992.

Years after his first two Hollywood books, Ellery Queen returned to Hollywood for a third novel, The Origin of Evil (1951). Once again, like The Devil to Pay, it deals with businessmen in L.A., not the movie industry. The central conceit of the story, “the household under siege from an avenger from the past”, is right out of the Sherlock Holmes tales.

Mystery

The Origin of Evil has an abundance of mystery plot. There are many separate mystery puzzle ideas:

● A core plot recalling Ten Days’ Wonder in its basic structure, about a common pattern in a series of events (solved in Chapter 14).

● A separate clue to the killer (solved in Chapter 15).

● Secrets of various characters: that of Delia (set forth in Chapter 1, solved in Chapter 9), that of Crowe Macgowan (set forth in Chapters 4 and 5, solved in Chapter 16).

● A puzzle about the past of the victims (start of Chapter 9, solved in Chapter 14). Its set-up (Chapter 9) is an example of the intensive police investigations into characters’ backgrounds that run through EQ. This look into the past of the business partners recalls a similar search into the past of the business associates (Chapter 5) in The Egyptian Cross Mystery. The solution reverses plot ideas found in “The Needle’s Eye”.

Early on, there is a nice if small example of an EQ specialty: an Impossible Disappearance (Chapter 4). It is solved right away. The disappearance plot is of a different, and perhaps simpler, structure, than those in many other EQ works. Instead, it shares a broad resemblance to another impossible crime involving footprints, the radio play “The Adventure of the Haunted Cave” (1939). Both tales have different puzzles and solutions, though.

This multitude of mystery is good. However, many of the individual ideas are fairly simple. They are solid, but not at the peak of EQ’s ingenuity. The Origin of Evil is somewhere in the middle rank of Ellery Queen’s achievement: a decent book, but not a classic. Still, it is a pleasure to read a book focused so strongly on mystery and detection.

The Finishing Stroke (1958) will also be an EQ novel with a major mystery in the Ten Days’ Wonder “find the pattern in a series” mode, and an “impossible disappearance of a person” subplot. The impossible disappearance will play a larger role in The Finishing Stroke than in The Origin of Evil, however.

Some of the characters turn amateur detective in the middle of the book, recalling the amateur sleuths who assist Ellery in Cat of Many Tails. These sections involve some decent detective work, tracking down the origins of objects used in the attacks on the house (Chapters 6,8).

Themes

The book expresses pessimism over the arms race, and describes Yugoslavia and Iran and Korea as possible places where war could break out: 50 years later this seems frighteningly prophetic. The Origin of Evil shows the start of the Korean War on the US home-front, just as Calamity Town did for the beginning of World War II. One suspects that EQ chose the Los Angeles setting largely for these aspects of the novel.

In addition to the arms race, there are two depictions of high tech environments in The Origin of Evil.

The Origin of Evil is blunt in its depiction of sexuality, like some other later EQ novels. Mickey Spillane was dominating the best seller lists at this time, and EQ was clearly writing in tune with the zeitgeist.

The Origin of Evil, like Ten Days’ Wonder, has a younger man in love with the beautiful wife of a powerful paternal figure of a man. In The Origin of Evil, the young man in love with the wife is Ellery himself. In both novels, the romantic triangle has undertones of an Oedipal conflict.

These books, along with Cat of Many Tails, are the main products of EQ’s Freudian psychoanalytic period (1948-1951). One suspects that such Oedipal symbolism was consciously intended by the author. I confess I don’t believe in Freudian psychology at all, and don’t see the artistic value of such imagery in the novels.

Characters

I did like the young hero. His name, Crowe Macgowan, seems to be inspired by Cro-Magnon Man, suggesting he is an evolutionary throwback. Crowe Macgowan is one of the eccentric, non-conformist characters, that often make Golden Age mystery fiction so interesting. Such characters have almost disappeared from most contemporary English-language crime novels, which instead glorify conformity.

Alfred Wallace is also an unusual character, who seems odder and odder as the novel progresses, and we learn more of his back-story.

The suspect Mr. Collier wanders through The Origin of Evil, making recurring appearances, and sometimes philosophizing about life. A similar recurring philosopher character is the young black man in The Tragedy of Errors.

Wed 23 Sep 2009

I don’t know why, but sometimes the last (and the shortest step) in a project takes the most amount of time before it finally gets done.

Case in point. I’ve been working on the Lending Library Mystery website for quite a while, and only over the weekend have I managed to get the last publisher’s page done.

This is the website that Bill Pronzini and I have been doing in conjunction with Bill Deeck’s reference book Murder at 3 Cents a Day, which is a complete list of all of the publishers whose mysteries were published almost solely for the lending library market in the late 30s through the 1940s, with blurbs and descriptions of all their offerings.

The best known of these may be Phoenix Press, but there were several others, including Hillman-Curl, Dodge Publishing Co., Gateway Books and more. Over the past year or more, Bill and I have been uploading cover images to the LLM website for almost all of the mystery and detective fiction put out by each of these small publishers.

The last two to have been completed are Mystery House, about which some information about the man who founded the company has been added, and Arcadia House, the last publisher to be included and for which cover images are now available.

Besides Bill, whose collection has been the source of all the cover images, thanks go also to Victor Berch, a tireless researcher into WorldCat and other arcane sources of publisher information.

Follow the links and feel free to browse around!

NOTE: The two covers shown are both Arcadia House titles.

« Previous Page — Next Page »