July 2010

Monthly Archive

Wed 7 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

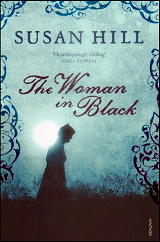

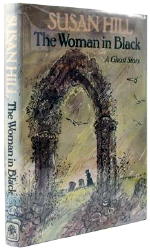

SUSAN HILL – The Woman in Black. David R Godine, hardcover,1986; trade paperback, November 1987. Originally published by Hamish Hamilton, UK, hardcover, 1983. Many later reprint editions.

It is Christmas, and solicitor Arthur Kipps’ family is clamoring for a Christmas ghost story, but he has no intention of sharing one, for the one ghost story Mr. Kipps knows is no tale for a cozy fire and a family setting …

They had chided me for being a spoilsport, tried to encourage me to tell them the one ghost story I must surely, like any other man, have it in me to tell. And they were right. Yes, I had a story, a true story, a story of haunting and evil, fear and confusion, horror and tragedy. But it was not a story to be told for casual entertainment, around the fireside on Christmas Eve.

The detective story and the ghost story as we know it both have a common ancestry in the birth of the Romantic Movement and the Gothic tale that developed as part of it, then morphed into the detective story on one hand and science fiction and fantasy on the other.

In particular, though, the ghost story has always had some appeal to many of the readers and writers of detective fiction, as if in the urge to explain away the world in terms of rational thought, there was also a desire to recapture the innocence of simple faith in the uncanny and the unnatural. That, and the ghost story often has a mystery to be solved at its heart, the mystery of why the ghost haunts in the first place.

There is a long list of psychic sleuths and no small number of writers of detective fiction who have dabbled in the supernatural including names such as Edgar Allan Poe, Joseph Le Fanu, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Dorothy L. Sayers, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Cornell Woolrich, John Dickson Carr, and many more — sometimes in standalone tales of the supernatural and in others in combination with the detective story. Even Barzun and Taylor included a section of ghost stories in their Catalogue of Crime.

And don’t forget that Sherlock Holmes, that most rational of rational thinkers, encountered a spectral hound, a vampire, and off the page, a mix of giant Sumatran rodents and worms unknown to science — and even when he and others explain away the supernatural, the faintest hint often lingers on the edge of the reader’s perception.

A handful of stories like Carr’s The Burning Court and Helen McCloy’s Through a Glass Darkly manage the neat twist of having it both ways, what Frank D. Sherry called the “Janus Solution,” both a rational solution and a supernatural one.

Susan Hill’s The Woman in Black is not only a ghost story, it appeared as a young adult novel originally, but for anyone who reads it the memory will linger. It is an exceptionally dark and powerful book. This is no Janus solution though. This is a full blown ghost story, and unrepentantly so.

Mrs. Alice Drablow of Eel Marsh House has died, and young solicitor Arthur Kipps is chosen by his employer Mr. Bentley to travel to the north of England, attend Mrs. Drablow’s funeral, and see to her estate. It’s an important assignment for Kipps and a chance for promotion so he can marry his fiancee Stella.

But rumors abound about Eel Marsh House, and as Kipps is taken in a pony cart across the dangerous marshes to visit the place he is struck by its unique appearance.

“I looked up ahead, and saw, as if rising out of the water itself, a tall, gaunt house of grey stone and with a slate roof, that now gleamed steely in the light. It stood like some lighthouse or beacon or martello tower, facing the whole, wide expanse of the marsh and estuary, the most astonishingly situated house I had ever seen or could conceivably have imagined.”

As in the modern gothic, houses are often virtually characters in many ghost stories. Here Eel Marsh House plays that role.

There he sees for the second time a mysterious and curiously malign woman in black he first spied at Mrs. Drablow’s funeral. He also experiences a terrifying experience of a woman and child killed on the marsh in a pony trap — or thinks he does, the mist is on the marsh and he can hear the tragedy, but not see it. But no such accident or missing persons are reported.

Doing a bit of detective work, he begins to piece together the story of Eel Marsh House together from the reluctant locals. No one wants to talk about Eel Marsh House, or the woman in black. Borrowing a dog for a companion from the landlord he is staying with, Kipps returns to Eel Marsh House to complete his inventory.

Gradually he learns of the tragedy that occurred at Eel Marsh House. A young woman and a child drowned in the marsh in a pony trap and their fate was tied to the death of a spinster woman who lived there, Jennet Humpfrye, who became obsessed with her sister Alice Drablow’s child and blamed her sister for the accident in which the child and a servant were killed in a pony trap on the marsh — in circumstances much like those Kipps experienced his first time alone in the mist.

Jennet Humpfrye is the woman in black, who, suffering a wasting disease, went mad in her grief for the child that was not hers — went mad and lingered on to take her revenge beyond the grave.

Again Kipps hears the crying of he dying child and the screaming woman on the marsh — and the dog hears it too, and he and the dog both almost lose their lives on the treacherous marsh as the woman in black watches them struggle and almost drown. Mr. Dailey, he landlord, arrives in time to take Kipps and the dog away, and reveal the final secrets of Eel Marsh House.

After his near death, Kipps’ health fails and he is haunted by the woman in black; his fiancee Stella comes to fetch him back to London when his fever breaks and away from Eel Marsh House and the malignant spirit of Jennet Humpfrye.

But neither she nor Eel Marsh House is finished with Kipps or us. Wherever Jennet Humpfrye has been seen there has been one “sure and certain result,” as Kipps learns from Mr. Dailey; “in some violent circumstance a child has died.” Time passes, Kipps and Stella marry, and they have a son …

The Woman in Black was highly acclaimed on publication, and is now considered a modern classic of the form. It has rightly been called a ghost story as Jane Austen might have written one. Like most such tales, it depends on an accumulation of tensions, small disturbances, and sudden shocks, and though a short novel, barely 50,000 words, it has the weight of a much longer tome.

A fully dramatized version of The Woman in Black was recently aired on BBC7 (it first aired in the 1990’s) adapted by John Strickland in four parts with John Woodvine as the older Kipps. It was adapted for television in 1989 with a teleplay by Nigel Kneale (the Quatermass serials and films) and directed by Herbert Wise.

Like the best of ghost stories, this one is simple, quiet, and builds to a moment of power and tragedy. Though it certainly has its moments of terror — Kipps lost on the marsh in a mist listening helplessly as a woman and child die in terror; a chair rocking in a closed room; the malevolent appearance of the title character; his near death on the marsh with the dog, Spider, lent him by the landlord of the inn; and his final confrontation with the woman in black — it is not about sudden frights or bloodshed.

There is no gore and no monster — only a terrible grief that leads to otherworldly revenge, and one man’s encounter with things that cannot be rationally explained — or dismissed.

I had always known in my heart that the experience would never leave me, that it was now woven into my very fibres, an inextricable part of my past … and then I prayed, a heartfelt, simple prayer for peace of mind, and for strength and steadfastness to endure while I completed a most agonising task…

They have asked for my story. I have told it. Enough.

Tue 6 Jul 2010

DEBORAH ADAMS – All the Crazy Winters. Ballantine, paperback original; 1st printing, July 1992.

This is the second in the recent series of mysteries taking place in Jesus Creek, Tennessee. Since the population of Jesus Creek is only 430 at the beginning of the book, and somewhat less than that at the end, you can only wonder (1) how long the series can last, and (2) how the number of murders per capita might compare to other metropolitan areas, such as (for example) the far more notorious New York City, a haven for killers and muggers if ever there was one.

But before going on any further, I should tell you right away that if you’re a reader fonder of hard-boiled mysteries than not, you should avoid this one with all the gusto you can gather. This one’s about libraries and librarians, and genealogy, and cute characters so lovably eccentric that Philip Marlowe and Sam Spade fans will run screaming from the room and not looking back.

It’s fairly clear that Deborah Adams has fallen in love with her characters, which is seldom a good thing to do. But no matter how you look at it, the plot really needs some help. It is so frail that Nancy Drew would have solved it in a minute, even on a bad day. With the wind blowing against her.

Or in other words, if you like whimsical people and even lighter-weight plots, you may find this series a good investment. Do read page 75 again, however, and tell me how two grown people (male and female) groping and tussling with each other at the victim’s funeral could in any way brighten your day.

— September 1993 (mildly revised).

[UPDATE] 07-06-10. Obviously I did not find much to recommend in this one, and I have not read another in Deborah Adams’ series of “Jesus Creek” mysteries. As I recall, however, while there is a recurring ensemble cast, the leading protagonist changes from book to book. Positive blurbs by Sharyn McCrumb and Joan Hess on the covers show that my opinion was not universal.

The Jesus Creek series —

1. All the Great Pretenders (1991)

2. All the Crazy Winters (1992)

3. All the Dark Disguises (1993)

4. All the Hungry Mothers (1994)

5. All the Deadly Beloved (1995)

6. All the Blood Relations (1996)

7. All the Dirty Cowards (2000)

Tue 6 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

REVIEWED BY TINA KARELSON:

JAMES W. HUSTON – Balance of Power. Wm Morrow, hardcover, May 1998. Reprint paperback: Avon, April 1999. Deluxe (tall) paperback: Harper, May 2009.

For the record, this is not the kind of book I normally read, but it was my local book club’s February book, so I manned up and dived in. To make an overly long story short, an American merchant vessel is seized by pirates pretending to be terrorists. They kill everybody.

The Speaker of the House invokes an obscure clause of the Constitution to circumvent the President’s preferred course of action.

No point. No character development. Or so it seemed. Imagine my surprise when the woman in the group who used to work in military intelligence enthusiastically presented the binder of research she’d put together to accompany the discussion.

Evidently, if a military-political thriller filled with the names and model numbers of boats and helicopters and amphibious craft is something you enjoy, this is an excellent, accurate example of the subgenre.

Tue 6 Jul 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini:

JOSIAH E. GREENE – Madmen Die Alone. Wm Morrow & Co., hardcover, 1938.

Joseph Parisi, a homicidal inmate at the Exeter Hospital insane asylum, turns up missing one night. Circumstances are such that it is unlikely he managed to escape on his own; and it appears the only person who could have freed him is brilliant research psychiatrist Dr. Hubert Sylvester.

But then Sylvester is found on the premises, brutally stabbed to death. Captain Louis Prescott of the local police is called in to investigate, and finds himself confronted with a maze of conflicting relationships among the hospital’s employees, not to mention attitudes and behavior that make him wonder if perhaps some of the keepers aren’t just as insane as their charges.

A second murder, of a shady Italian restaurant owner named Luigi Toscarello, intensifies the hunt for Parisi; it also implicates Parisi’s family, thereby opening up a whole new can of worms for Prescott to sift through. Did Parisi kill both Sylvester and Toscarello? Did someone else kill both of them? Or are there two murderers, one at the asylum and one outside it, each with different motives?

Despite some first-novel flaws — viewpoint lapses, too many exclamation points — and a bunch of ethnic stereotypes, Madmen Die Alone is a solid novel of detection, with a well-depicted background, interesting insights into psychiatry circa 1938, and a neatly clued solution. Fans of fair-play deductive puzzles should enjoy it.

Greene published one other mystery — The Laughing Loon (1939), set in the Minnesota lake country — before abandoning the genre to write mainstream novels.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 5 Jul 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

HARRIETTE R. CAMPBELL – Crime in Crystal. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1946. No UK edition.

As Simon Brade sits in the study of the Rev. Christopher Tyrell Dawes preparing to ask him about his new client, Lady Vanessa Lorrister, a seemingly crazed man rushes in and confesses to having strangled Lady Vanessa.

The vicar doesn’t believe him, but it turns out that Lady Vanessa was definitely strangled. That didn’t kill her, however. Someone had come along a bit later and beaten her to death with a poker.

The vicar contends that Lady Vanessa was loved by all — in more ways than one, it turns out. But her husband, a possible future prime minister, didn’t care for her, nor did his secretary who had ambitions for him. It is also possible that Lady Vanessa was the head of a black market in clothing during the war and was prepared to tell all, thus jeopardizing others.

If it weren’t for his income from detecting allowing him to purchase precious jade and porcelain, Brade wouldn’t detect at all. Furthermore, he is at a loss without his fellow sleuth, Inspector Ivy of Scotland Yard.

Ivy determines the facts. Brade then “sees” connections, working with his “bricks.” As Ivy explains it:

“They’re Chinese toys — little ivory cubes. Mr. Brede writes things on them. There’s one for Time and Opportunity, marked with initials on as many sides as there are suspects — see? One for Motive,” — he counted them off on his fingers — “one for Evidence, one for what he calls Blurs on the picture — that means ‘objections to the case’ against the suspect — one for the General Picture, and one for Conclusions. That’s six.

“Well, he jiggles them about and studies them and goes to sleep over them, and somehow or other — the Lord only knows how, begging your pardon, sir — he gets the right answer.”

Brade, at least in this novel, isn’t all that interesting. The other characters, however, particularly the Reverend Dawes, who accompanies Brade in his sleuthing, make up for his blandness.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 10, No. 2, Spring 1988.

Bio-Bibliography: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

CAMPBELL, HARRIETTE R(ussell). 1883-1950. Born in New York, the daughter of the state’s attorney-general; married a Scotsman and settled in London. SB = Simon Brade.

The String Glove Mystery (n.) Knopf 1936 [SB]

The Porcelain Fish Mystery (n.) Knopf 1937 [SB]

The Moor Fires Mystery (n.) Harper 1939 [SB]

Three Names for Murder (n.) Harper 1940 [SB]

Murder Set to Music (n.) Harper 1941 [SB]

Magic Makes Murder (n.) Harper 1943 [SB]

Crime in Crystal (n.) Harper 1946 [SB]

Three Lost Ladies (n.) Heinemann-UK 1949

Mon 5 Jul 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

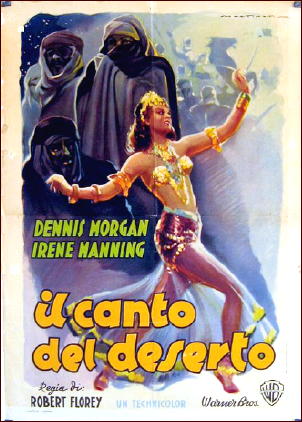

THE DESERT SONG. Warner Brothers, 1943. Dennis Morgan, Irene Manning, Bruce Cabot, Lynne Overman, Gene Lockhart, Faye Emerson, Jack La Rue. Screenwriter: Robert Buckner, based on the play co-written by Oscar Hammerstein II. Director: Robert Florey. Shown at Cinecon 27, Hollywood CA, September 1993.

After the success of Casablanca earlier that year, this vintage operetta was updated, setting the nomadic Berber Riffs of northern Morocco against the dastardly Nazis and shot in eye-popping technicolor.

Florey is noted for his stylish films and this was a restored beauty. Both Jim Goodrich and I gasped at the stunning overhead angled shot of a belly-dancer as she fell back onto the floor and spread her multi-colored skirt to fill the screen.

It’s also a film for fans of Bruce Cabot, with a world-weary but effective one-note performance by Gene Lockhart as a Riff cabaret owner. Fine singing of a lovely score by Dennis Morgan and Irene Manning.

Editorial Comments: This film, as I understand it, has never been shown on television. Complications over the copyright of one of the songs perhaps, and it sounds reasonable, given the amount of money involved, or is it just the principle? The movie had been made once before, in 1929, which was barely into the sound era, but at least parts of it were in Technicolor, believe it or not. It starred John Boles and Carlotta King in the two leading roles.

And it was filmed once again, in 1953, this time with Kathryn Grayson and Gordon MacRae. This is, of course, the version that most people have seen. (But not me. In 1953 you couldn’t drag me to a movie like this. Based on an operetta? Are you kidding?)

Mon 5 Jul 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller:

STEPHEN GREENLEAF – Death Bed. Dial Press, hardcover, October 1980. Paperback reprints: Ballantine, May 1982; Bantam, December 1991.

Stephen Greenleaf has received a great deal of critical acclaim for his novels featuring John Marshall Tanner, former lawyer turned private eye.

Tanner’s territory is the San Francisco Bay Area, where his cases take him into the homes of the rich and powerful, as well as into the lowest dives in the city; the author draws heavily on his knowledge of politics, business, and local events to flesh out Tanner’s investigations.

Greenleaf has been hailed as the successor to the Raymond Chandler/Ross Macdonald tradition, and it is easy to see why. Like Philip Marlowe and Lew Archer, Tanner is less a fully developed character than an observer. Hints are thrown out about his past and private life, but they are not elaborated upon, and frankly the reader doesn’t care.

Greenleaf makes extensive use of simile, as Macdonald did, but with far less success; often he seems to be stretching a point, reaching for a likeness that simply doesn’t come off. He is a successor to the tradition of the hard-boiled private eye developed by these writers in the sense that he is an imitator, and his work makes one wonder why we need further imitations.

Death Bed begins with a scene reminiscent of Philip Marlowe’s meeting with Colonel Stem wood in The Big Sleep. Maximilian Kottle, dying millionaire, wishes to hire Tanner to find his estranged son, Karl.

Kottle waxes philosophical about life and death — perhaps too much so for a man in such pain and close to death — and Tanner agrees to find his son for him. Karl’s mother, flamboyant romance novelist Shelley Withers, can give few clues to her son’s whereabouts, but through solid detective work — one of the strong points of this series — Tanner traces Karl, and is getting close when Belinda Kottle, beautiful young wife of Maximilian, calls to say Karl has contacted his father and is coming to see him.

Shortly afterward, Maximilian dies, and Tanner considers the case closed. He is then free to undertake a search for missing investigative reporter Mark Covington, but soon discovers the Kottle case is not only still open, but also linked to the journalist’s disappearance.

There are a few surprising twists here, but the case builds to a rather predictable conclusion, and the primary villain (there are many, of various sorts) is introduced so late in the narrative that the solution comes a little out of left field. Chandler and Macdonald simply did it better.

Other novels featuring John Marshall Tanner are Grave Error (1979), State’s Evidence (1982), and Fatal Obsession (1983).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Sun 4 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

STEPHEN GREENLEAF – Southern Cross. Wm Morrow & Co, hardcover, November 1993. Paperback reprint: Bantam, February 1995. John Marshall Tanner #9

After being disappointed by Valin and Lyons this year, and finding Jerry Healy’s mediocre for him, Greenleaf was my last PI hope for 1993. *Sigh.*

Tanner returns to the Midwest for a reunion of his college graduating class, looking for answers to questions he’s not even sure how to ask. He meets old friends there, and an old lover, and one of the friends asks for his help.

A civil rights worker in the 60s, the friend is being threatened by a group of racists. He doesn’t know who they are or why they’ve targeted him, but he does take them seriously, and wants Tanner to find out these things and make them go away.

Still looking for his own answers, Tanner accepts, and [heading for Charleston SC] wanders into a magnolia-scented world that he doesn’t know. As you might expect, everybody has secrets, and as usual few of them are happy ones.

Greenleaf is different from most PI writers in that he deals with what people do to one another, not only on the small, personal scale, but in terms of larger societal issues as well. He is a social and political liberal, and this attitude infuses his books.

Here, of course, he has much to say about bigotry and race, and what it’s done to us all. As always, Tanner is as much a man of thought and meditation as of action; another defining characteristic of Greenleaf’s books is that they tend to be much more philosophical than those of other PI writers.

Cross is a detective story and a mystery of sorts, but there is little violence. Greenleaf’s writing is as powerful as ever, but the story itself didn’t hold together for me. Tanner makes too many connections with too little evidence, and the motivations of the eventually unmasked villain were simply not believable.

Too many words were spent on Tanner’s angst and Greenleaf’s thoughts on racism, and not enough establishing the connections between the characters that might have rationalized the story.

I didn’t dislike the book — I like Greenleaf’s writing too well — but it disappointed me considerably.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #10, November 1993.

Previously reviewed on this blog:

Beyond Blame (by Steve Lewis)

For a long overview of Greenleaf’s books by Ed Lynskey, and an interview he and I did with the author several years ago, may I recommend that you go here on the main Mystery*File website. You’ll find a complete bibliography there as well.

Sun 4 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

HULBERT FOOTNER – Sinfully Rich. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1940. Reprinted as a Philadelphia Inquirer “Gold Seal Novel”: August 3, 1941. Hardcover reprint: Books Inc., 1944. British edition: Collins Crime Club, hc, 1940.

Hulbert Footner was a Canadian-American writer who, nearing the age of forty, began publishing mystery tales about the time World War One ended.

He soon made a good name for himself in the field, particularly with his tales of an early female detective, Madame Rosika Storey. (Madame Storey is who he is remembered for today, when he is remembered.)

Many of his novels and stories are more accurately characterized as thrillers; and even his tales of putative detection seem more “mystery” than detection, with the author not paying scrupulous attention to the fair play concept (allowing the reader the chance to solve the mystery for him/herself through deciphering clues fairly provided by the author).

Still, Footner’s works often have “zip” and are entertaining enough, just not necessarily mentally over-rigorous. A good example of his style is one of his later works, Sinfully Rich (1940).

In Sinfully Rich, a sixty-seven year old millionaire’s widow who has been living it up in New York City smart society after the death of her tightfisted husband is found dead after a big night, all her jewels missing.

The police and medical examiners think she died naturally and then was robbed, but ace journalist Mike Speedon (who is to inherit a modest sum of $100,000 dollars from the “old dame”) shows the experts what for (journalists — what don’t they know?). He proves the millionairess was murdered (disappointingly so, as the putatively amazing murder method is taken lock, stock and barrel from Dorothy L. Sayers and Unnatural Death, published a dozen years earlier).

In the classical British manner there is are two wills, a missing nephew, a dubious lawyer, a scheming gigolo and household full of suspicious employees and servants (personal secretary, personal maid, first housemaid, butler and “second man”).

What more could a mystery fan ask for? Well, a more clever plot, perhaps, but maybe that is being uncharitable on my part. There were many, many mystery novels published in those days, and one cannot reasonably expect sheer brilliance from all of them.

What is most enjoyable about the book is the interactions of the characters up to the resolution of the mystery. Footner casts a wryly amused glance over the foibles of the wealthy, who have, seemingly, a great deal of time and money to burn.

Footner treats his readers to glimpses of the high life, US version, but he also encourages them to mock what they see, through the focal character of the cynical, clever, manly reporter, such a classic figure in American film and literature from this period. If it’s rather like a watered-down Dashiell Hammett highball (The Thinner Man, say), at least it goes down smoothly, with no unpleasant aftertaste.

There is investigation, but no really satisfying ratiocinative process. (I was rather reminded in this respect of the British novelist J. S. Fletcher, whose mystery novels probably were more popular during the Golden Age in the United States than they were in his native Britain.)

Because there really isn’t fair play, Footner is able to maintain until the end of the novel suspense concerning the question “Whodunit?”; yet some of the fun, for me anyway, is lost.

If, as Robert Frost opined, free verse is like playing tennis without a net, so is a mystery that does not practice fair play. You can still enjoy it, but you feel a bit cheated! Still, I’ve read far worse mysteries from the period than Sinfully Rich. (See my Carolyn Wells reviews!)

Editorial Comment: A list of the “Gold Seal” novels published in the Sunday Philadelphia Inquirer (mid-1930s to late 1940s) can be found online here. Many of them were mysteries; others appear to be straight romances.

Sun 4 Jul 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

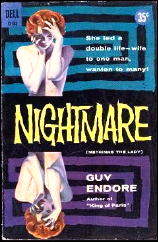

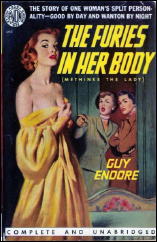

GUY ENDORE – Nightmare. Dell D183. 1956. Originally published as Methinks the Lady, Duell Sloan & Pearce, hardcover, 1945. Also reprinted as The Furies in Her Body, Avon #323, pb, 1951.

Film: 20th Century-Fox, 1949, as Whirlpool, with Gene Tierney, Richard Conte, José Ferrer, Charles Bickford; director: Otto Preminger.

I bought Nightmare (Dell, 1956) at a used book store back when I was Fifteen or so, thinking I was buying a Sex Book — well, look at the cover, can you blame me? — and I read it, thinking I was reading a sex book.

So you can imagine my surprise when I got to the end and discovered it was actually a Mystery and perhaps a pretty clever one.

The Narrator tells the story talking to herself (literally, as she narrates first-person, she keeps interrupting to ask questions and argue with herself) starting with the day she became a compulsive thief, flashing back to relate how she married a prominent psychologist who believes her to be the one woman completely free of neuroses, then moving on to tell how she beat a shoplifting rap by seducing a cop, was troubled by recurring dreams of prostitution — described with some relish by the author, so you can’t blame a kid for thinking this is a Sex Book — and finally how she killed a woman (in a cat-fight of pornographic proportions) was tried for murder, found guilty, and then … and then …

And then Endore suddenly reveals that there was a Murder Mystery going on here all along, in a surprise wrap-up that really dazzled the adolescent I was back in those days. When I re-read it last month, the ending seemed a bit strained, but nicely handled, and still enjoyable.

Endore’s prose could be charitably described as Soupy, his frequent ramblings pointless, and his concentration on Sex Sex Sex as … well, as lurid and sexy. There’s also a 1940s pop-psychology infusing the book that gets pretty trite sometimes, but I have to admire a talent that could conceal a killer so neatly. Nothing like it since Lolita … which was also a Sex Book.

Previously reviewed on this blog:

Detour at Night (by Bill Deeck)

« Previous Page — Next Page »