August 2010

Monthly Archive

Sat 28 Aug 2010

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

JO BANNISTER – A Bleeding of Innocents. Frank Shapiro & Liz Graham #1. St. Martin’s Press, US, hardcover, 1993. Macmillan, UK, hc, 1993. Worldwide Library, paperback, 1997.

Jo Bannister has written other mysteries, and won an EQMM prize, but this is the first of her work that I’ve read. It’s also the first in a new series.

The police force in Castlemere, England is in disarray. A Detective Inspector has been killed and a Detective Sergeant injured in what may have been a hit and run; or may, as the Sergeant believes, been a deliberate murder engineered by a local racketeer.

Chief Inspector Shapiro brings in an old colleague, DI Liz Graham, to temporarily replace the slain DI, and she is greeted by the shotgun murder of a retirement home nurse. At the same time, she must try to work with the injured Sergeant, a difficult person who had a close relationship with his slain boss, and who is determined to pin the death on the racketeer he suspects.

I have a predilection for British police stories, and I’m happy to say that this is a pretty good one. It isn’t of John Harvey or Reginald Hill caliber, but it’s competently done and well written. The third person narrative is straightforward, and shifts among the three police officers.

Characterization is not really in depth, but sharp enough that Graham and the Sergeant are brought to life decently, though Shapiro was less well developed. The plot was the weakest link, but tolerable.

I did think that the book ran on a bit at the end after the real denouement, with perhaps a little too much talk, but that’s a minor cavil. On limited exposure, I think Bannister fits comfortably in the middle of the pack with which she’s chosen to run.

— Reprinted from Ah, Sweet Mysteries #10, November 1993.

The Shapiro & Graham “Castlemere” series —

1. A Bleeding of Innocents (1993)

2. Sins of the Heart (1994) aka Charisma (US)

3. Burning Desires (1995) aka A Taste for Burning (US)

4. No Birds Sing (1996)

5. Broken Lines (1998)

6. The Hireling’s Tale (1999)

7. Changelings (2000)

Jo Bannister has also written four books in her Dr Clio Rees (Marsh) and Harry Marsh series; two books with Mickey Flynn; two in a series about columnist Primrose “Rosie†Holland; and nine books featuring Brodie Farrell, a woman who “finds things for a living.” She’s also written nine standalone novels, not all of which are crime related.

Fri 27 Aug 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

ELSIE N. WRIGHT – Strange Murders at Greystones. International Fiction Library, US, hardcover, 1931.

As Holmes has warned us, it is unwise to theorize without facts. Nevertheless, I am tempted to speculate that someone, either an enemy or a practical joker, told Wright she should write a book.

That same someone may also have suggested to International Fiction Library that it should publish a book regardless of merit. Unfortunately, the twain met.

Of course, it’s possible the typesetter had a hand in the confusion. The many typos, particularly the missing and misplaced quotation marks, provide some confirmation of this hypothesis.

Perhaps the typesetter forgot to include a few of the manuscript pages, thus leading to at least this reader’s confusion.

Anyhow, Thatcher Graham, master of Greystokes and an absolute rotter, is found dead in his library with the back of his head bashed in. Apparently, let me hasten to say; this, as well as other alleged facts presented by the author, is not definite.

Inspector Kelley comes to investigate. Kelley, the author tells us, is a keen and intelligent detective who has worked his way up the ranks. As portrayed, however, he is an utter buffoon who solves most of his cases by beating confessions out of suspected crooks and browbeating witnesses.

His working principle is that anyone with an alibi is probably guilty — why else have need for an alibi? — and anyone without an alibi is patently guilty.

Arresting the fiancé of Graham’s daughter is the only wise move Kelley makes. Dumb as he is, he almost had to do it. But then Sergeant Brock, who has been left in the house for no particular reason except the author’s need, is killed, somehow, by a creature with “piercing green eyes.”

The police are called again, they arrive, they search the grounds, they depart. What about Brock’s death? Oh, it’s mentioned a few pages later that the police are upset about Brock’s being killed, but that’s it.

Our hero, Jack Pelton, whom Kelley still suspects even after Brock’s death, gets out of jail. Arriving at Greystones, he and his fiancee, Polly, go out to search the grounds. Polly says that the police already have done so. Jack says they didn’t know what they were looking for but he does. What is it? Neither he nor the author says; indeed, no search is made of the grounds.

Jack does find a bloody dagger — by sitting on it. This weapon is important to two people, both of whom crave it. Why? After burning incense and checking chicken entrails, I must conclude that it is the only sharp instrument on the estate. There’s no other apparent reason for wanting it.

Approaching the dog kennels during their non-search of the grounds, Jack and Polly spot the green-eyed creature entering the kennels. When they go in, the creature has disappeared and there are bloodstains, which leads Polly to conclude, on no other evidence, that a dog has been killed.

Inspector Kelley comes wandering by, and they all go in to lunch, without a word being said about the creature or the dog.

A new cook is hired. Why? Apparently the author felt she needed alleged comic relief, so she introduces a black who talks about the “debbil” and “hants” and has hysterics. What happened to the other cook? Probably only the typesetter knows.

Searching subterranean tunnels with Polly, our hero notices that she is shaking badly. Bravely — oh, he’s brave but not bright — he gives her a revolver and walks in front of her. Later he fires that same revolver that she had not given back.

Inspector Kelley had provided the revolver, apparently carrying two for those occasions when he might need to give one away. The next time he comes, however, and two guns are needed, he has only one.

Kelley is also cheap, for the pistol contains but a single bullet. Our hero had examined it earlier and had no complaints, but if he’d had more than one bullet the novel might have ended too soon — that is, for the author’s and publisher’s purpose.

He discovers the single bullet when he wisely is “trying the revolver to see if it had jammed.” Later Kelley’s revolver, most unusually, does jam.

Wright is unstinting in her use of verbal and plot cliches. The word horror appears at least 50 times, she being unable to convey the real or imagined item. There are numerous “blood curdling” laughs, an idiot who utters “gutteral” — is the author or the typesetter toying with us here? — cries, trapdoors, a butler who acts strangely, a dotty housekeeper with a secret, concealed passages, and a genuine, unadulterated mad scientist with a 20-year grudge.

This is Wright’s first and only mystery. Wisely she wrote no more. What could she have done for an encore?

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 2, Spring 1989.

Fri 27 Aug 2010

ANN PARKER – Silver Lies. Poisoned Pen Press, hardcover, September 2003; trade paperback, April 2006.

A first novel, and for a mystery, it’s a long one, some 420 pages, but for a work of historical fiction, the page count might be about right. It’s 1879, and Leadville is a booming small metropolis in Colorado, the inhabitants of which are afflicted with “ever-present cold, lingering homesickness, and the pangs of silver fever.”

Inez Stannert is one of the few women in the town, co-owner of a flourishing saloon, and since the town marshal seems to be totally uninterested, she’s also the only person willing to investigate the possible murder of the town’s assayer, who’s been found trampled to death on the frigid muck of a nearby street.

Adding to Inez’ concerns is her husband, who’s been missing for several months, but the new minister in town seems more than willing to help her forget. The legendary Bat Masterton also makes an appearance, but it’s little more than a cameo, as Inez and the Reverend J.B. Sands end up doing all of the heavy lifting.

As a mystery, it’s adequate. It works better as a historical novel — life in this rough-and-tumble corner of the world is brought to life quite effectively in two quite opposite and surprising ways: the scenic wonder of 19th century Colorado and the wretched environment it had to have been for anyone actually trying to live there.

The story in Silver Lies is less effective as far as the romantic elements are concerned, falling prey to some fairly stand-by cliches, and much of the author’s work is undone, paradoxically, by some better-than-average characterization that has to be retrofitted, and abruptly so, to make the rather lurid conclusion work.

Acceptable, and maybe more so, depending on where your interests lie, but if there’s a paperback forthcoming, you might choose to put it off till then.

— August 2003

Note: This review has been revised slightly since it first appeared in Historical Novels Review.

The Inez Stannert “Silver Rush Mystery” series —

1. Silver Lies (2003)

2. Iron Ties (2006)

3. Leaden Skies (2009)

Fri 27 Aug 2010

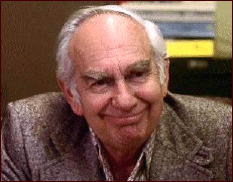

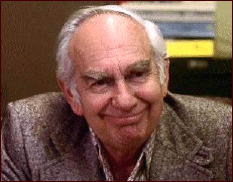

A TV Review by MIKE TOONEY:

“Who Killed Who?” An episode of Dragnet 1970 (Season 4, Episode 15). First air date: 29 January 1970. Jack Webb (Sergeant Joe Friday), Harry Morgan (Officer Bill Gannon), Jim B. Smith (Captain Brown), Herb Vigran (Paul Woods), Marshall Reed (Sergeant Hughes), Don Ross (Sergeant Doherty), Chuck Bowman (Jerry), Marco Lopez (Pedro Martinez, uncredited). Writer: Michael Donovan. Creator, producer, director: Jack Webb.

Joe Friday and Bill Gannon are called downtown to a run-down three-story flophouse to investigate a multiple shooting. Before they can begin their investigation, one of the victims on a stretcher leaves Friday with a baffling dying clue — “oft one,” he says — but neither Friday, Gannon, nor Captain Brown can figure it out — not at first, anyway. The lack of any eyewitnesses further complicates the case.

Methodically investigating the crime scene, Friday and Gannon note two dead bodies lying on the floor in front of a TV set that, like the victims, has also been shot once.

Other clues include a number of expended 9-millimeter shells (later shown to be from a German-made Luger); a torn piece of red cloth with a shirt button clutched in one of the victim’s hands; and blood smears along the banister leading to the second floor, but which curiously end halfway up — with nary a sign of the perpetrator.

Three dead, and very little evidence of how it went down. Later the significance of an apparently unrelated phone call to the police just before the massacre would become clear —but it’s only when Friday and Gannon discover a FOURTH body that the full story of the progress of this crime can finally be told.

This show is just like one of those “Five Minute Mysteries” come to life. With its unusual emphasis on forensic evidence, this Dragnet episode could serve as a model for bloated crime scene investigation shows like CSI: Miami in how to compress an engrossing story into half the length. The only other Dragnet I can recall that put such emphasis on the forensics was “Homicide: Cigarette Butt.”

One of the reporters Friday has to keep in check for the sake of his investigation is played by Herb Vigran (1910-86), who had over 300 appearances in movies and TV, usually playing annoying smart alecks, sometimes for laughs but often for hisses.

The prime suspect in this case was played by Marco Lopez (b. 1935), who is primarily remembered for his regular role in another Jack Webb production, Emergency! (1972-78), playing a fire fighter cleverly named Marco Lopez. If memory serves, in “Who Killed Who?” he has no dialogue.

You can see “Who Killed Who?” on Hulu here, and “Homicide: Cigarette Butt” here.

Editorial Comment: Herb Vigran, whose face you see in the image above — did you recognize him? — was in seven episodes of this later Dragnet series, almost his longest-running gig. Most of the characters he played in his over appearances in movies and TV did not have names. The parts he played were often identified only as Salesman, Policeman, Judge, Fireman, Delivery Man, Waiter, Baggage Man, and So On. Most of his roles were speaking parts, however, and whenever you saw or heard him, you recognized him immediately.

Thu 26 Aug 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[13] Comments

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

MIGNON G. EBERHART – The Pattern. Doubleday Doran & Co., hardcover, 1937. Bestseller Mystery B55, digest-sized paperback, 1944. Also reprinted as Pattern of Murder, Popular Library #167, paperback, 1948. (Later Popular Library editions reverted to the original title.)

In Mignon Eberhart’s The Pattern, a nasty wife who will not consent to a divorce is murdered at a lake resort outside Chicago, making life very difficult for our hero and heroine, the now widower and the sweet young thing he should have married.

The Pattern is one of my favorite Eberhart’s, in part because the author dials down the emotional anxiety meter a bit, allowing the reader to just enjoy the story and think about whodunit.

The lake setting is a little different for Eberhart (no ancestral mansions) and is well conveyed. Also there is more perspective on other characters, not just that of a constantly fretting heroine getting beaten down by the police and by her reliably bitchy women “friends.”

As in the slightly earlier Fair Warning (1936) and Danger in the Dark (1937), Eberhart makes some attempt to provide both clues and an actual demonstration of a deductive process on the part of the detective (Jacob Wait, who makes his next-to-last of three appearances here). There is also some nice shuddery creepiness concerning poisonous spiders that have an unsettling propensity to get into cabins.

A good job by a consummate genre professional.

Editorial Comment: Also by Mignon G. Eberhart and previously reviewed by Curt on this blog: The Glass Slipper.

Thu 26 Aug 2010

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

KATE ELLIS – The Merchant’s House. Piatkus, UK, hardcover, 1998. St. Martin’s, US, hardcover, 1999.

Genre: Police procedural. Leading character: Sgt. Wesley Peterson; 1st in series. Setting: England.

First Sentence: The child flung his tricycle aside and toddled, laughing, toward the basking cat.

A university graduate in archeology and the first black police officer in Tradmouth, DS Wesley Peterson begins his first day at work with a murder. The body of a young woman has been found off a cliff path, the damage to her face rendering her unrecognizable.

Wesley’s university friend, Neill, is heading a team of archeologists on the site of a 17th century merchant’s house in town when the skeleton of a child is found. A fellow officer is dealing with the mother of a missing toddler who is adamant her son is still alive in spite of a lack of clues.

Can a clue from the past solve a crime in the present?

To find a book which is a skillful combination of archeology and police procedure is definitely in my “happy-reader” zone. Ms. Ellis does just that and much more. Although the locations are fictional, I was ready to pack my back and go. Those who are familiar would know the differences, but for those who don’t, the locations are visual and real.

Not only is there a nice introduction to Wesley, but to all the book’s major characters. One thing particularly refreshing is that the police officers all like one another and work as a team. There is an odd man out, but you don’t feel he’ll be there long. It’s not just the primary characters Ms. Ellis brings to life, but the secondary characters as well. I never had to question who a character was or why there were there.

It can be a tricky business, bringing together four plot lines, but it works. The information from the 17th century is provided in diary excerpts as chapter headings, while fascinating, does not intrude on the present-day investigations.

The dig at the merchant’s house plays to Wesley’s background and as an escape from issues at home. The kidnapping is largely the responsibility of another team, and the murdered girl is Wesley’s primary investigation. Yet Ms. Ellis cleverly designates Wesley as the hub which brings together the various spokes of the wheel in a way I didn’t predict until it was revealed.

The Merchant’s House is a very good police procedural in which the plot unfolds not by flash, but bit-by-bit, following the clues. It is filled with great characters, dialogue, humour, and a plot that kept me reading. Happily there are many more books ahead in this series.

Rating: Very Good.

The Wesley Peterson series —

1. The Merchant’s House (1998)

2. The Armada Boy (1999)

3. An Unhallowed Grave (1999)

4. The Funeral Boat (2000)

5. The Bone Garden (2001)

6. A Painted Doom (2002)

7. The Skeleton Room (2003)

8. The Plague Maiden (2004)

9. A Cursed Inheritance (2005)

10. The Marriage Hearse (2006)

11. The Shining Skull (2007)

12. The Blood Pit (2008)

13. A Perfect Death (2009)

14. The Flesh Tailor (2010)

15. The Jackal Man (2011)

Editorial Comment: LJ, your last sentence seems to be rather an understatement!

Wed 25 Aug 2010

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

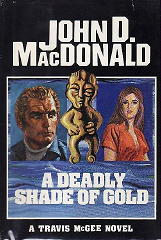

JOHN D. MacDONALD – A Deadly Shade of Gold. Gold Medal d1499, paperback original, 1965. UK edition: Robert Hale, hardcover, 1967. First US hardcover edition: J. B. Lippincott, 1974. Reprinted many times.

“Drink to me my friend. Drink to this poisonous bag of meat named McGee. And drink to little broken blondes, a dead black dog, a knife in the back of a woman, and a knife in the throat of a friend. Drink to a burned foot, and death at sea, and stinking prisons and obscene gold idols. Drink to loveless love, stolen money, and a power of attorney,

mi amigo. Drink to lust and crime and terror, the three unholy ultimate’s, and drink to all the problems that have no solution is this world, and at best a dubious one in the next.”

The fifth of the Travis McGee series, and the first labeled a double novel ( or what would become the standard length for entries in the series), A Deadly Shade of Gold is probably the most interesting book in the McGee canon historically for undermining virtually everything critics, fans, and attackers tend to say (and repeat endlessly) about John D. MacDonald and McGee.

“Perhaps you are an angel of death … the branch that breaks, the tire that skids, the stone that falls. Perhaps it is not wise to be near you.”

In this book McGee not only doesn’t save a woman with redemptive sex, he doesn’t save one at all, suffers guilt over taking advantage of an emotionally vulnerable woman ( “Much of lust is a process of self delusion … back in my own bed I said surly things to jackass McGee about taking rude advantage of the vulnerable, about being a restless greedy animal …”), flat out turns down one such woman’s offer (or Meyer’s on her behalf), is rescued by an attractive woman who initially doesn’t want to have sex with him, watches their relationship deteriorate, and goes home sadder but wiser.

If this is what some critics call the swinging sixties lifestyle as Hefner and Playboy defined it I must have missed a few issues or misread them. In addition he kills a sunbunny ( “… genus playmate californicus …” who is trying to kill him “Hero McGee wins the shootout. He’s death on sunbunnies.”).

This isn’t as unusual as it seems. Critics of Mickey Spillane, Ian Fleming, and even Ernest Hemingway all tended to write a good deal of nonsense about their work based on a superficial and often unsympathetic reading. If it were only critics who made these incomplete statements it would be bad enough, but fans don’t seem to have read the books either in many cases.

McGee here views himself with as jaundiced an eye as any contemporary bachelor in the post feminists world and judges himself more harshly than any critic could ( “We are all guilty. Also, we are all innocent, every one.”). If there is anything here paternalistic, it’s McGee’s constant worry that he will do more harm than good to the women in the case — and all the innocents, and even some of the guilty, who tend to get smashed along the way.

MacDonald doesn’t think women are equal to men — if anything he thinks they are superior ( “I got the hell away from her before I had more awareness than I could comfortably handle.”)

One fan-site that calls MacDonald’s books “classy trash” says more about the fan than MacDonald. Judith Krantz was classy trash. John D. MacDonald was a major American voice working within the boundaries of popular fiction.

Classy trash seldom bears re-reading, MacDonald’s work begs it. Ian Fleming was classy trash, and glad to be that, but MacDonald had higher aspirations and achieved them even within the confines of a series character like McGee. Calling his work classy trash because it appeared in paperback originals is singularly narrow.

Hemingway wrote for Esquire, Fitzgerald the Saturday Evening Post, and Nabokov for Playboy — Mackinlay Kantor, Stephen Becker, Robert Wilder, and Vivian Connell all wrote paperback originals (and all for Gold Medal) — you can’t always judge a writer by his milieu.

A Deadly Shade of Gold opens with the death of McGee’s old friend Sam Taggart, who has just returned to Florida looking to reconnect with Nora Gardino ( “… a lean dark vital woman …”), an attractive local boutique owner he walked away from when he went to Mexico.

With Taggart’s brutal murder McGee finds himself drawn into a case that involves some ancient gold figures Sam has found. The trail leads him to an auction house in New York where he sleeps with a young woman ( “With a brassy forlorn confidence …”) to get information and feels exploited and exploiter for it ( “The physical act, when undertaken for any for any motive but love, and need, is a fragmenting experience.”).

This leads him with Nora to a small (fictional) Mexican fishing village ( “For all the years the generations of them, in the dust and mud and sea smell, had lived and worked and died in this coastal pocket …”) where he is drawn into the illegal trade in antiquities run by a ruthless American, and the schemes of some violent Cuban exile groups.

McGee makes some forays against the American behind the racket ( “… a dull, self-important, rich, silly, sick little man.”), meets a whore who loved Taggart and who is quite human, real and lacking a heart of gold, emotionally smashes an aging playgirl to find out what he needs, feels guilt about exploiting Nora’s grief sexually and gets Nora killed (or blames himself for it), returns to Los Angeles, meets the fabulous Connie ( “I have a very rational approach to my needs and desires.”), who agrees to help him but wants nothing to do with him as a sex partner ( “It would take us too long to find out who was winning, and in the process I might lose.”) because they would fight for control of the situation, avenges Sam, scores a nice profit, damn near gets killed, is rescued by Connie ( “I do not think she expected anything for herself …”), has a brief affair with her that is redemptive for neither of them, and ends up fleeing back to Florida before all that is left are bitter memories ( “There is one thing Senor McGee that is the exact opposite of death.”).

All that remains of McGee is an ironic Knighthood, a spavined steed, second class armor, a dubious lance, a bent broadsword, and the chance, now and again, to lift into a galumphing charge at capital E Evil, brave battle oaths marred by an occasional hysterical giggle.

Remind me again about the jovial boat bum who saves all the damsels with his charm and sexual charisma and patented sexual healing while living the Playboy lifestyle:

“The guilty have all been punished?”

“Yes, along with the innocent.”

Are we reading the same books?.

And always there are the little moments many of us read MacDonald for, snippets from here and there:

A Southern pusgut who fancied himself a liberal.

She could have stood there forever, Lot’s wife.

… the challenging promise of great feminine warmth.

A smear of blood has a metallic smell. It smells like freshly sheared copper,

“She is disaster prone, compelled by a bruised heart.”

At sea level the heat was moist, full of the smell of garbage and flowers and a faint salty flavor of the sea.

It is a bedroom gun, with a brash bark like an anxious puppy.

From the shadowy corner came the sound of the bride’s febrile chuckle, and soon he walked out, obsessed with the legality of it all, the permissive access, and all the fishermen at the bar turned slow heads to appraise the departing ripeness of her, and seemed to sigh.

Anxiety makes dreams all to vivid.

She was not pretty. She was merely strong, savage, confident …. and muy guapa .

She was not legend. She did not have a heart of gold, or a heart of ice.

… the deep, ancient, rhythmic affirmations of the flesh.

The ones with no give, the ones with the clear little porcelain hearts shatter.

“His name is Lagarto. Lizard. Hammer-headed thing with a mean eye.”

… the slightest touch would ease her out of that jump suit like a squeezed grape.

These are just a few at random, simply page flipping. This too is another reason to read MacDonald, and why he is not simply classy trash, and why attention should be paid, and the memory of his best work should be accurate and clear, and not the mere repetition of what we have read elsewhere and been told and accepted without testing and knowing for ourselves.

He, and we, deserve better.

John D. MacDonald was the only writer to ever win the National Book Award in the mystery category (for The Green Ripper) it is time we recall who he was, what he did, and admit his achievements go beyond just entertaining us. He wrote a portrait of a place and time and world as real and as accurate as has ever been written, and it is our loss if we forget that or lessen it because he is not as politically correct as some would like.

Much of what he had to say about the American character and American society is as true and accurate today as it was when it was written, and while we should admit his flaws and that he was a man of his world and time, it is past time to discard our own prejudices and honestly evaluate his remarkable contribution.

He was a remarkable writer for his time, or any time. We are only cheating ourselves if we throw him out because we changed while failing to recognize that in many ways the world he showed us has not.

Wed 25 Aug 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller:

JOHN D. MacDONALD – The Green Ripper. J. B. Lippincott, 1979. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback, June 1980. Reprinted many times since.

This relatively recent entry is one of the worst in the Travis McGee series. It is bloody and violent, involving a strange paramilitary cult and all the attendant cliches, and McGee’s personal vendetta against the cult seems to rob him of his more human qualities.

In a prior novel (The Empty Copper Sea, 1978), McGee fell in love with a woman named Gretel Howard. She lived with him aboard the Flush for a while, but recently has moved out to be closer to her job at Bonnie Brae, a “combination fat farm, tennis club, and real estate development.”

The relationship is still as warm as ever, though, and when Gretel dies suddenly of a mysterious and debilitating illness, Travis is devastated. Not so devastated, however, that he doesn’t wander sideways into inquiring about the strange events that occurred at Bonnie Brae right before Gretel’s death and determining that her death was somehow murder.

The rather thin story line leads McGee from Fort Lauderdale to Ukiah, California, looking for a man known as Brother Titus who heads an organization called the Church of the Apocrypha. Posing as a man looking for his daughter, Travis locates an encampment, formerly a religious commune but now as closely guarded as a top,secret military base. He is imprisoned, then recruited, and the events that transpire are too brutal and depressing to reiterate.

If there is anything positive about the resolution of this novel, it is that McGee eventually recovers; unfortunately, it is a recovery that fails to recognize that vengeance seldom leaves any real satisfaction in the soul of the avenger.

Other, much better, titles in the McGee series are The Deep Blue Goodbye (1964), The Quick Red Fox (1964), A Deadly Shade of Gold (1965), The Girl in the Plain Brown Wrapper (1969), and Dress Her in Indigo (1969), and The Lonely Silver Rain (1985).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 24 Aug 2010

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

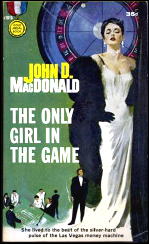

JOHN D. MacDONALD – The Only Girl in the Game. Gold Medal s1015, paperback original; 1st printing, July 1960. First hardcover edition: Robert Hale, UK, 1962. Reprinted many times.

If there was justice in the world, writers would rise each morning and bow three times in the direction of John D. MacDonald’s grave. If that seems a bit extreme, read this description of a typical night in a Las Vegas casino, better still “listen” to it, its cadences and its rhythms:

Casino play was exceptionally heavy. All tables were in operation, and the customers stood two and three deep around the craps and roulette. The murmuring crowd noises blended with the chanting of the casino staff, the continuous roar of the slots, the music from the Afrique Bar and the Little Room, and the muffled burst of applause from the Safari Room where the dinner show was coming to an end. As he worked his way through the throng, Hugh was once again aware at how truly joyless these casino crowds really were.

When play was this heavy there was a special electric tension in the air, but there was something dingy about it. There was laughter, but no mirth. This was the raw sweaty edge where luck and money meet in organized torment. Money is equal to survival. So it is as mirthless as some barbaric arena where slaves are matched against beasts. People in casinos ignore each other. It is a place where each man is intensely and desperately alone, but you can still play Casino games, even online by using this comparison of top 10 online casino here.

There is a tendency to discuss MacDonald’s work as if he was yet another suspense novelist, and while he wrote some fine suspense novels, I have always thought of him as first and foremost a novelist. His concerns are those of the mainstream of American literature, and while few writers had his skill or ability at creating suspense, what sets him apart from almost every other writer in the field in that novelist’s eye.

His special skill was not only in creating suspense and character but illuminating the darker byways of the everyday world of business and life. His plots and characters intersect at the place where the day to day world of business breaks down and lines are crossed morally and criminally. No one ever took a more jaundiced or more clear eyed view of the morality — and lack of it — of the average American business enterprise, whether it be a Florida real estate deal gone bad, a con game out of control, or the operation of Vegas casinos.

Vegas and its casinos are the perfect milieu for both MacDonald’s savage moral eye and his very human and sometimes morally fragile characters. Hugh Darren, the hero of this novel, is the assistant manager at the Cameroon’s hotel, one of the big casinos. He is ideally suited to his job, a person with a sharp mind, people skills, and a clear eyed view of the world.

The Cameroon was once the worst run hotel on the strip. Hugh changed all that. But this is a city and a world where success isn’t measured just by results. Sometimes it is measured by whose knife is in your back or at your throat.

Hugh has just run afoul of Max Haines, who runs the casino side of the operation who “knows a lot about how things run around here.” He knows things about their boss Al Marta too, and about secrets the manager of the hotel might not know — or care to know.

Hugh wants to run the hotel at a profit. Max is old school and believes the hotel should lose money to better support the casino, the real source of money. And making sure the margins for the casino stay where they always have been is a job Max does, and boss Al Marta turns his head from, at any cost.

As might be expected, there are two notable examples of MacDonald women in this one. First is Betty Dawson, “a tall brunette with unusually dark blue eyes, and a loveliness of face that was reminiscent of Liz Taylor.” Betty is a singer (“I’ve got no voice and I can’t play much piano …”) who works in one of the hotels rooms and has recently fallen hard for Hugh, the kind of stand up guy she never had in her life before: “We just didn’t have this kind of thing in stock when you first started to trade with us, Betty,” is how she sees it:

Don’t ever love me, Hugh. Just let me love you. I’m ready for hurt. I’m braced for it. You are worth too much to ever fall in love with what I have become.

Betty also acts as a hostess at the hotel. It’s not exactly prostitution — she doesn’t have to sleep with customers — but she does have to lead them on. She knows who and what she is, she doesn’t yet know what it will cost her beyond what it has already cost, her self respect, and something of her heart and her soul.

But for the time being Betty is the happiest she has been in a long long time, and anyone who has ever read John D. MacDonald should know that excess joy is never a good sign.

Sex is one of MacDonald’s great themes, not only the healing power of good sex, but the destructive dangers of the other kind. He sees it both as a blessing and a curse, a redemption and a damnation. His heroes tend to redeem the women in their lives both with sex and with compassion, but it is never cut and dried.

Too much has been made over the redemptive aspect of sex in MacDonald’s books, and not enough perhaps of the awful toll it sometimes takes. Contrary to what some critics like to suggest, a good man is not always enough to save a MacDonald heroine, and even in the McGee books there is a stubborn refusal to allow easy answers.

His heroes are often catalysts in the life of the women in his books, but MacDonald seldom suggests that is enough. It is only one part of healing, one part of life, not everything.

Some critics would do better to actually read MacDonald, rather than simply repeat what they have read about him.

The other MacDonald woman is Vicky Shannard, “… in her thirtieth year, a cuddly dumpling, a pwetty widdle pigeon, a blonde, pink and white, cushiony little cupcake …” who parlayed a history of stripping and living as a professional guest to marriage to Temple Shannard a moneyed older man from New Providence, a golden tongued promoter who operates in the Bahamas and is now in Vegas. But lately their marriage is drifting apart and coming to the Cameroon isn’t going to help.

Vicky is a type MacDonald is never particularly kind to, but he does draw them as they are with due prejudice, but also with an honest eye. She isn’t a monster and Tempe isn’t a victim. They are just people who can’t overcome who and what they are.

At heart John D. MacDonald has the pure American streak of the Calvinist about him. He is attracted to and repelled by the glamour of money and power. Glitter, sin, and easy money bring out the savage in him even as he cannot ignore them or stay away.

All of these people might not create quite so much drama anywhere else, but as Hugh explains to Vicky in a statement that might be the theme of the novel:

“Vicky, dear, when you give people the maximum opportunity to make damn fools of themselves, sexually, financially, and alcoholically, in an environment that makes movie sets look like low-cost housing all sorts of things can happen.”

Finally there is Homer Gallowell of Fort Worth, Texas, a figure that appears in many MacDonald novels in many forms. Homer is a canny old coot, a player and an operator, the sane voice of a man who “had the hard bitten look of a man who had spent the first half of his life sleeping on the ground.”

Gallowell is the kind of individualist who MacDonald always champions over the corporate mind of any business enterprise, smart, tough, straight, and sentimental about only two things — good men and women and good booze.

He’s a fairly common figure in business related novels of the fifties and sixties, the last of a breed before buttondown minds accompanied button-down collars, before the bottom line became the moral standard.

Homer has come to Vegas and the Cameroon to beat the house at its own game.

Homer is an old friend of Betty Dawson too, which is why Max Haines thinks she may be able to play him, because Homer is the one thing Vegas fears more than card counters and con-men — an intelligent gambler with enough money to give them a run for their money, to play their odds, and to win. Max had used Betty for this kind of thing before:

“Now that wasn’t so bad was it?”

“It was as easy as cutting your own throat, Max.”

To give him full credit, MacDonald makes the operations and philosophy of a casino and the machinations of Homer, Max, Al Marta, and Tempe Shannard as suspenseful as any spy novel or bank heist. No one wrote as compellingly about the high pressure world of money and power.

As the strands of the novel tighten into a single skein, the center falls apart as it so often does in MacDonald’s novels. The sham that is Tempe and Vicky’s marriage begins to shatter, Betty’s past begins to catch up with her, and Hugh Darren’s basic morality and honesty is about to come in conflict with Vegas version of the bottom line.

It seemed to Hugh as he sat there that this was a very bad place on the face of the earth, that it was unwise to bring to this place any decent impulse or emotion, because there was a curiously corrosive agent adrift in this bright desert air. Here, attuned to the constant clinking of the silver dollars in forty thousand pockets, honesty became watchful opportunism, friendship became a pry bar, love turned to licence, and legitimate sentiment drowned in a pink sea of sentimentality.

It would not be a good thing to stay in such a place too long, because you might lose the ability to react to any other human being save on the level of estimating how to use them, or how they were going to use you. The impossibility of any more savory relationship was perfectly symbolized by the pink-and-white-and-blue neon crosses shining above the quaint gabled roofs of the twenty-four-hour-a-day marriage chapels.

We are all familiar with MacDonald’s use of color- coded themes, but someone should write a paper on his use of the color pink. He seems to embody all the sins and flaws of the American Dream in the color pink.

The crisis comes when Betty Dawson, her own morality awakened by being asked to play Homer, defies and crosses Max Haines, and through her Hugh Darren faces his own moral and ethical crisis. But when Max and Al push Hugh too far and hit him too hard, he reacts in the true manner of a MacDonald hero and with a little help from Homer …

“What is the one thing in the world most important to these fellers? What do they love the best.”

“Money.”

“And what’s the greatest weapon in the world?”

“Money.”

Hugh and Homer bring down Max Haines and his pals, but at a cost they would neither of them have cared to pay. Some heroines can’t be saved and some dragons are never really slain.

The cabs are bringing the marks in from McCarran Field to fill up the twelve thousand bedrooms. At all the places the gaudy roster of the strip — El Rancho, Sahara, Mozambique, Stardust, Riviera, the D.I. Sands, Flamingo, Tropicana, Dunes, Cameroon, the T-Bird, Hacienda, New Frontier — the pit bosses are watching all the money machines.

Smoke, shadows, colors, sweat, music, the bare shoulders of lovely women, the posturings of the notorious — and that unending, indescribable, chattering roar of tension and money, I shall never see it again, but I will always know it is going on, without pause or mercy, all the days and nights of my life.

The names have changed, the strip is bigger and gaudier than ever, more a playground and fantasy than ever, but MacDonald’s savage critique remains as true and as well observed as before. No one ever looked harder, longer, or more honestly at the phony sentiment, cruel lies, and emotional paucity of big money and big business.

Whether in the standalone novels or the Travis McGee books, whether writing about crime or business that deteriorates into crime, his great theme was an anger and even grief over the soul-numbing results of wounded people in a society with too few second chances.

MacDonald, in the true tradition of the American novel, and not just the hard-boiled school, still echoes Twain’s Huck Finn at the end of his adventures. “I been there before.” That echoes across American literature, that sense of loss and frustration, that realization that life indeed goes on, and we have all “been there before” and will be there again.

Tue 24 Aug 2010

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini:

JOHN D. MacDONALD – The Good Old Stuff: 13 Early Stories. Harper & Row, hardcover, 1982. Fawcett Gold Medal, paperback, 1983.

MacDonald, like so many other writers, learned his craft in the pulps. Between 1946 and 1952, he sold hundreds of crime stories to such magazines as Black Mask, Dime Detective, Detective Tales, New Detective, Mystery Book, and Doc Savage (as well as other short fiction to science fiction, fantasy, sports, and western pulps).

A few of these criminous tales have been reprinted here and there over the years, but the greater percentage languished in (mostly undeserved) obscurity until 1981 , when Martin Greenberg, Francis M. Nevins, and Walter and Jean Shine — MacDonald aficionados all — persuaded John D. to collect the best of them.

They chose thirty stories; on rereading those thirty, MacDonald considered all but three worthy of reprinting. (Minor changes were made to update certain references for the sake of clarity; otherwise he allowed them to stand as first published.)

But the final total of twenty-seven was deemed too many for a single book; the result is two volumes — The Good Old Stuff and its companion, More Good Old Stuff (Knopf, 1984).

The thirteen stories in this first volume demonstrate MacDonald’s considerable range within the mystery! detective format, as well as his narrative talent and power. Among them are such gems as “The Simplest Poison” (whodunit); “Death Writes the Answer” (biter-bit); “Noose for a Tigress” (pure suspense); “Death on the Pin” (character study — and the world’s first and only crime story about bowling); and the novelette “Murder for Money,” whose protagonist, Darrigan, is a prototype of Travis McGee.

No fan of MacDonald’s work should miss either this batch or the fourteen equally excellent and diverse stories in More Good Old Stuff.

Until these volumes, MacDonald’s collected short fiction was restricted almost entirely to selections from such slick magazines as Cosmopolitan, Collier’s, and Playboy — fifteen stories in End of the Tiger (1966) and seven in Seven (1971).

His only previously collected pulp story was the title piece in the 1956 gathering of two novellas, Border Town Girl. Another two-story collection (both from the pulps), this one unauthorized, appeared in 1983 under the title Two.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

« Previous Page — Next Page »