August 2010

Monthly Archive

Fri 6 Aug 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

BILL PRONZINI – The Hidden. Walker & Co., hardcover, November 2010. (Available for pre-order online.)

No one currently writing orchestrates the elements of the suspense novel with half the finesse of Bill Pronzini. If that were all — and it would be enough — he would be our best suspense novelist, but he also gets inside of the head of the characters in his novels and gets them into our heads, all done with simple elegance, and without the sturm und drang of many lesser writers.

We don’t just identify with his characters, we experience with them. We get to know them; innocents, and not so innocents, madmen, lovers, and killers, all drawn simply with a few deft strokes that none the less present fully developed characters — people we recognize and know, and sometimes are.

Jay and Shelby Macklin are a young couple in crisis, emotional and financial crisis. Jay is emotionally remote and withdrawn (“All his life he had been a closed book, not just to her and others, but to himself too.”), Shelby is hurt and has fought for their marriage about as long as she is willing to (“Twelve years of marriage to him had sucked the youth out of her.”).

The two of them are taking a Christmas vacation at a friend’s vacation home on the rugged Northern California coast.

Their timing could be better. Since midsummer the coast has been haunted by the so called Coast Line Killer, a murderer whose motives are obscure and who seems to strike randomly. For a number of reasons this holiday is a less than wise choice for the troubled couple, not the least Shelby’s nyctaphobia, her fear of the dark:

… she’d never quite lost her fear of the dark.

She had it as far back as she could remember. Not of ordinary darkness, the light-tinged kind where you had some limited vision of objects or shapes. Of blackness so complete you couldn’t see anything at all, the kind a blind person must feel …

Pronzini has already introduced us to the killer, and his motive, to protect the rugged coastline from any and all intruders, so we know ahead of time what sets him off, and wait breathlessly for the young couple to cross his deadly path. And even here Pronzini rings in changes and surprises that both fill our expectations and take us in new directions.

His killer is no monster, no sex-obsessed cartoonish serial killer leaving a trail of extravagant sado-masochistic crimes behind him, but instead a quiet man become reluctant and rather tired avenger of the vulnerable coast. It is because his crimes seem so mundane and so reasoned that he is frightening.

He is the stuff of headlines, not nightmares. He is frightening for being familiar, for being someone we might know, might see in our daily lives, might not notice until it is too late:

Clouds shifted away from the moon, and the wind and the slow-breaking waves lit up with a kind of iridescent white glow. A long yellow white streak appeared on the ocean’s surface, extending out over some of the offshore rocks where the gulls nested, giving their limed surface a patch-painted look. He paused to take in the view. Nice night. He liked nights like this, quiet, peaceful, empty, as if he had the sea and the scalloped shoreline all to himself.

As has happened in past Pronzini novels the setting, the Northern California coast where Pronzini lives, is also a character in the novel as is the weather, in this case a brutal winter storm.

And with those elements set in motion he then begins to add the twists and refinements. Not far from where Jay and Shelby are staying two other couples are also vacationing in a sort of domestic hell that makes the Macklin’s problems look simple.

Human nature, the weather, too great passion and passion dying, a madman, human weakness, and human fears — these are the ingredients Pronzini stirs into his mix, having already warned us with his choice of epigraphs from Georges Bataille and Friedrich Nietzsche as well as his title that it is not the obvious dangers that should concern us, but those things we hide from others and from ourselves.

Theme, plot, setting, and character are one, a grand design, and a unity, not merely disparate entities thrown together.

The monsters are not in the outer dark, but the inner dark we create within ourselves. Shelby has more to fear from that inner dark than anything lurking on the outside, even the Coast Line Killer:

The night seemed alive with shrieks, whistles, fluttery moans.

His Coast Line Killer is, much like the great storm that spawns the breathless climax of the novel, only a force that brings those hidden things to the surface. Not all the violence, nor all the crime in the novel arises from the disturbed man’s actions though like the storm his presence and his actions bring things to a head. There are other currents and other crimes that will test Jay and Shelby to their limits, and in Jay’s case an enemy more implacable and deadly than any serial killer, and begin the process of healing — or end their lives.

There are no easy answers in Pronzini’s novels, whether suspense or his tales of his private detective Nameless. Heroism can come down to putting one foot in front of another because you have to, to showing simple courage in face of madness, to overcoming a phobia, a childhood trauma, ourselves, to discovering how much you love another, and to just doing the right thing. Survival can hang on those small things as well. Sometimes heroism and love comes down to saving each other:

He was just a man who’d finally stepped up, finally proved to himself — and, if he was lucky, to her — that he wasn’t a failure or loser after all.

The Hidden is a fairly short novel in these days of bloated best sellers, tightly written and tightly plotted, but never mechanical or obvious. It is strongly cinematic, but the pleasures, as always with Pronzini, are in the writing and not merely his visual sense.

His characters are recognizable people, not merely pawns to the suspense element. There is always a sense that they exist beyond the confines of the novel, that they are people and not merely characters.

You will reach the end of the book emotionally drained and with nerves on edge, but like the master that he is, Pronzini manages to let you off the hook without ever quite letting you forget just how tight the pinch was.

It is not a book you will close and walk away from. Things linger, not just the frights, but also those moments of recognition when he cuts close enough to the bone for most of us to recognize ourselves and the hidden within us.

Bill Pronzini doesn’t need much introduction here. He is a six time Edgar nominee, three time winner of the Shamus award, winner of the Grand Master award from the Mystery Writers of America, creator of the Nameless series of hard boiled mysteries, anthologist, genre historian and critic, western novelist, and has collaborated with numerous writers including Barry Malzberg and wife mystery novelist Marcia Muller.

But to put this book in perspective, it would be a major book and a fine suspense novel from any writer. It is perhaps the best tribute we can pay to a writer as accomplished as Bill Pronzini to simply say that if he had no history as a writer and had written nothing else, this book would mark him as one of the finest voices in the suspense field today.

Such consistent quality may sometimes lead us to take a writer for granted. We should not. A new book by Bill Pronzini should be a reason for celebration. This one certainly is.

Thu 5 Aug 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[4] Comments

A REVIEW BY RAY O’LEARY:

DERMOT MORRAH – The Mummy Case Mystery. Paperback reprint: Perennial Library, 1988. Hardcover editions: Harper & Brothers, US, 1933; Faber & Faber, UK, as The Mummy Case, 1933. Also published in the US under the British title: Garland, hardcover, 1976.

It’s the end of term at Beaufort College, Oxford, and Professor Benchley, the Egyptologist, has acquired a mummy from his arch-rival Professor Bonoff, a Russian with whom he has been carrying on an academic feud. The feud has apparently ended with Professor Benchley conceding defeat, but he has plans to sell the mummy for twice as much as he paid for it.

However, he turns down the offer of a wealthy American collector whom he had invited to lunch that afternoon. That night, while the Commemoration Ball is going on, a fire breaks out in Benchley’s rooms and, when it’s put out, the remains of one man are found.

A verdict of accidental death is brought in by the coroner’s jury but two of the younger Professors Sargent (law) and Considine (the Assyriologist) have their doubts — there should have been two burnt bodies found: Benchley’s and that of the mummy. So the two begin to investigate.

This is an entertaining light-hearted example of the Golden Age detective story, with some pleasant humorous touches thrown in. I read this when it first was issued in paperback, although I probably figured it out then as I did now because it uses a variation of a plot situation I’ve encountered in several whodunits and for which I have a rule that, if I stated it, would be giving away the solution.

Bibliographic Note: This is the author’s only mystery novel. It is included in Victor Berch’s checklist of Harper’s Sealed Mystery Series.

Also note that Mike Grost comments on this novel on his Classic Mystery and Detection website. Check it out here.

Thu 5 Aug 2010

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

E. LOUISE CUSHING – Murder Without Regret. Arcadia House, hardcover, 1954.

During a party after the reading of a will, one of the guests presumably commits suicide. Barbara Hillier finds the corpse and aids Inspector MacKay of the Montreal police in the investigation of an undoubted murder later.

Striving as always to say something good about any novel, I can report that this one has very large type and a great deal of space between the lines. Thus, it’s only about a 30-minute waste of time.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 11, No. 2, Spring 1989.

Bibliographic Data: [Taken from the Revised Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin.]

CUSHING, E. LOUISE. Pseudonym of Mabel Louise Dawson. Inspector Richard MacKay appears in all four books below.

Murder’s No Picnic (n.) Arcadia House, 1953.

Murder Without Regret (n.) Arcadia House, 1954.

Blood on My Rug (n.) Arcadia House, 1956.

The Unexpected Corpse (n.) Arcadia House, 1957.

Thu 5 Aug 2010

LEA WAIT – Shadows at the Fair. Pocket, paperback reprint; 1st printing, July 2003. Hardcover edition: Scribner, July 2002.

Since Lea Wait herself is a long-time antique dealer, one specializing in prints, it comes as little surprise that Maggie Summer, her detective heroine in this, the first in a series, is one also. An antique dealer, that is, specializing in prints.

And that’s the part of the story that’s the most fun to read, even though most of Maggie’s discussion of her stock in trade and other shop talk with her customers is quite irrelevant to the mystery — the death of another dealer who’d set up at same Rensselaer Antique Show as Maggie.

In fact, both customers and dealers are beautifully portrayed in all of their foibles and eccentricities, of which (from my own personal experience) customers and dealers have many. To put it mildly. Also right on in terms of characterization is Ben, the mildly retarded nephew assisting one of Maggie’s friends, who’s also set up at the show.

Which brings me to the part I didn’t care for so very much. Ben is accused of the murder — which allows the show to go on, with (as the police say) the killer caught. A fatal flaw for many a cozy: there’s far too much laughing and joking and kidding around when murder’s been done — with poor Ben sitting there alone in the lockup.

I was also ready to add another source of dissatisfaction, that of predictability, but I have to tell you that while the first two-thirds of the murder investigation falls into that particular category, I did not see the ending coming. My socks are still on, but it opened my eyes a little wider.

And so. With all of the pluses and minuses added in, subtracted off and weighed up against each other, the bottom line? An average sort of mystery, but with a nudge or two in the right direction, one that could have been improved upon immensely. There’s promise here, but apart from the antique dealer background, the rest is fairly uneven, at best.

— July 2003

The Maggie Summers “Antique Print Mysteries” series —

Shadows At the Fair (2002)

Shadows On the Coast of Maine (2003)

Shadows On the Ivy (2004)

Shadows At the Spring Show (2005)

Wed 4 Aug 2010

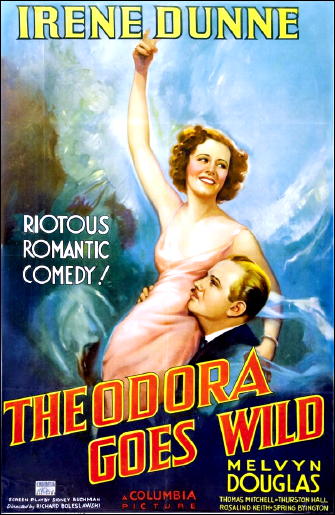

THEODORA GOES WILD. Columbia Pictures, 1936. Irene Dunne, Melvyn Douglas, Thomas Mitchell, Thurston Hall, Elisabeth Risdon, Margaret McWade, Spring Byington. Director: Richard Boleslawski.

Humor is a funny thing. This is the lead-off movie in a boxed set of Screwball Comedies (Volume Two), and not only did I never laugh, but there are elements in this film that I actively disliked, which seldom happens. (I do screen the movies I choose to watch ahead of time.)

Well, OK, maybe I did smile once or twice.

The theme here is small-town holier-than-thou gossips and self-selected morality leaders – the small town being Lynnfield, somewhere in New England, where the local literary society is up in arms with the publisher of the local newspaper (Thomas Mitchell), who’s started to serialize the latest racy romance novel that’s sweeping the country.

Little do the members of the local literary society know that the author, Caroline Adams, is one of their own: Theodora Lynn, who lives with her two aunts in Lynnfield (and yes, the town is named after their family), and who teaches Sunday school classes and plays the organ at church.

In constant fear of her secret identity being revealed, Theodora (who of course is played by Irene Dunne) goes to New York to meet her publisher (Thurston Hall) to make him keep his promise to stay absolutely mum.

The comedy potential is there, all right, as I’m sure you can see, but the man she meets, the artist who designed the risqué cover of her book, Michael Grant (Melvyn Douglas), is such an ill-mannered oaf, an utter boor if not an outright cad, it is impossible to understand what she sees in him.

Of course she reacts to his constant taunts by going on an all-out nightclub drinking spree with him, even to the extent of ending up in his apartment to wrap up the evening. (Nothing much happens, but I imagine in 1936, the entire audience was holding their breath.)

Fleeing back to Lynnville the next morning, Theodora is tracked down by her not-so-secret admirer, who manages to make himself even more dislikable, if that’s possible, but of course in the movies, anything’s possible, isn’t it?

When the tables turn on Michael Grant, though, and do they ever, that’s when the training wheels come off, and Theodore lives up to the title of the movie – does she go wild? yes! – and it’s Michael Grant who faces …

I won’t tell you what he faces, but it was nice to see him in the predicament he finds himself in. Nice, but not particularly funny.

If you were to ask me, which I guess you are, since you’ve read this far, I liked Irene Dunne’s character a lot more when she was playing the innocent Theodora (although a Theodorea with a secret) a lot more than I did the wild Theodora, with a vast array of designer dresses and hairdos that do not especially flatter her.

Rather than wild, she looked to me more like a small child playing dress-up, but what had to pass for wild on the screen in the mid-1930s was a lot more innocent than what you can see on your TV screen today.

Irene Dunne was nominated for an Oscar in the role, and from all accounts, I’m in the minority in my opinion of this movie, and I thought you should know that too.

Wed 4 Aug 2010

A REVIEW BY CURT J. EVANS:

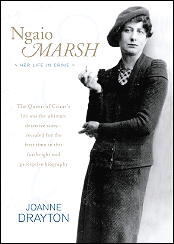

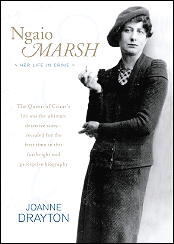

JOANNA DRAYTON – Ngaio Marsh: Her Life in Crime. HarperCollins, Australia, hardcover, January 2008; softcover, 2009.

The first biography of Ngaio Marsh following Margaret Lewis’s Ngaio Marsh: A Life (1991, reprinted by Poison Pen Press, 1998), is this book by Joanna Drayton. Published by HarperCollins of New Zealand, it is evidently unavailable for direct purchase in the United States, providing, perhaps, further evidence that big publishers are losing interest in marketing Golden Age British authors in the their greatest potential market (Christie and Sayers excepted).

In Britain, Harper recently has reprinted Marsh’s ouevre in three-volume, 800-plus page ominbuses; yet in the U.S. no new edition has been seen, I believe, since the late 1990s, about a dozen years ago. This is a shame, because I notice from Amazon.com reviews that Marsh seems to be more positively received in the U.S. than in Britain; and in New Zealand, Marsh’s home turf, she has been, according to Joanne Drayton, largely forgotten as a writer. (Rather amazingly, considering that she must be, one would think, the country’s best-selling native author.)

Perhaps this explains why it has been hard to find reviews for Drayton’s book, which was published two years ago. When one compares the publicity in Britain given to the 2008 biography of Agatha Christie (the first substantive new one in nearly twenty-five years), Laura Thompson’s Agatha Christie: An English Mystery, with the paucity of that afforded Ngaio Marsh: Her Life in Crime, the contrast is striking. It’s too bad, because Ngaio Marsh unquestionably is one of the most significant writers of classical mysteries associated with Britain’s Golden Age of detective fiction.

Yet, while I would have liked for Drayton’s book (and resultingly Ngaio Marsh) to have received more attention than it did, I have mixed feelings about how much it has added to the prior work on Marsh by Margaret Lewis.

First, a comment on physical aspects of the two books. HarperCollins designed an excellent, striking jacket, attractive endpapers and chapter headings and even provided a built-in book marker in the manner of Library of America, all of which is quite nice to see (though, as is often the case today, the paper is too thin and the print too light and indistinct, especially in contrast with the Poison Pen Press edition of Lewis’s book).

However, I was rather amazed to see that the Drayton book, though it has notes and a select bibliography, is lacking an index! I find that quite irritating.

Going on — finally — to the subject matter, I find the Drayton book superior to the Lewis in some ways, inferior in others. On the negative side, Drayton’s book seemed less informative on Ngaio’s youth and her parents, especially her father, than Lewis’s. I felt I learned more about Marsh’s home influences and family background from Lewis.

Drayton gives much more information about Marsh’s life in the theater, but then Lewis writes a great deal about this as well. (I admit these sections of both books I skimmed over.)

On the other hand, Drayton’s discussions of Marsh’s detective novels are superior to those by Lewis. This was an area I felt Lewis rather skimped, given the importance of this work. (Let’s be honest: would two biographies of Ngaio Marsh have been published had Marsh not been a very successful mystery author.)

Nonetheless I was not fully satisfied with Drayton’s discussion of the books. She never really integrates themes throughout Marsh’s work, so the whole thing comes off as interesting in spots, but piecemeal (the discussions of the later books from the last fifteen years of Marsh’s life are less thorough as well — or are the books just less interesting?). Drayton provides a better Golden Age context for Marsh’s writing, yet it’s really just the four “Crime Queens” yet again.

The sole focus on the Crime Queens is somewhat ahistorical in my view. For most of the Golden Age, there were two reigning Crime Queens: Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers.

Allingham didn’t really fully emerge in her resplendent royal robes until the trio of Flowers for the Judge (1936), Dancers in Mourning (1937) and The Fashion in Shrouds (1938), I would say.

And Marsh was not well recognized until after her trio of Artists in Crime (1938), Death in a White Tie (1938) and Overture to Death (1939).

Even then, Marsh was only picked up by a big U.S. publisher, Little, Brown and Company (publishers of J. J. Connington), after Overture to Death was published; and it was Little, Brown who secured Marsh’s crown safely on her head with Surfeit of Lampreys (1940/41), still today generally considered her best book.

So while Allingham and Marsh were Crime Queens, their reigns commenced during the waning of the Golden Age. (Arguably, they had something to do with that waning, at least if by “Golden Age” we mean a period when the puzzle was considered the keystone of the detective novel — it’s clear many readers read Marsh and Allingham more as novels of manners than as pure detective novels.)

We also get the usual W. H. Auden stuff about how “normality was always restored” in Golden Age detective novels, etc. Well, that’s not true, but, hey, hopefully I’ll get my whack at this in print with the “Humdrum” books and the follow-up, more general survey I’m working on now.

Despite my carping, I’ll emphasize again that the discussion of Marsh’s detective fiction is more interesting in Drayton than in Lewis (though make sure you read Doug Greene’s introduction to Alleyn and Others: The Collected Short Works of Ngaio Marsh as well!).

Sometimes Drayton is a little ingenuous. She makes much of the “Marsh Million Murders” (this is a chapter title in her book), when, in 1950, I believe it was, Penguin reprinted ten Marsh titles in 100,000 printing runs. (Lewis noted this as well, but did not make such a fuss about it.)

Drayton references Howard Haycraft in Murder for Pleasure from nearly a decade earlier about how the average detective novel sold only 1500-2000 copies (because most were read through libraries, not purchased).

But Drayton is comparing apples and oranges to some extent here. Clearly, the Marsh Penguin deal is impressive, but Drayton needed to look at post-war paperback sales of other authors for a really accurate comparison. This was the time of the great paperback revolution and other authors, like, say, Spillane, Chandler and Stout were blowing them out in paperback too, surely.

I smiled a bit when Drayton wrote that Marsh’s output of ten novels in seven years was “extraordinary.” Well, it’s certainly not slacking, but it’s not extraordinary by genre standards of the time, as a look at the output of, say, Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Freeman Wills Crofts or John Street makes clear.

I was reminded of an old SCTV skit where Olivia Newton John gets booked on a talk show with some porn stars and when they find out she’s made nine films or what have you in her whole career, they scoff, telling her they make nine films in a month!

To be fair, however, Lewis had some odd moments too, like when she writes that The Nursing Home Murder is Marsh’s most popular book — can this really be right? there is no citation of this claim — and when she states that that in the U.S. after WW2 Marsh was “much preferred” to Agatha Christie, because people there no longer wanted to read about Hercule Poirot.

However, Drayton’s book is a biography, not a literary study, so presumably some people will be most interested in this book for what it tells us about Marsh’s personal life. The big story here is Drayton speculates about Marsh, having been a lesbian, something the previous biographer eschewed doing.

Marsh “was fiercely protective of her private life,” the jacket flap tells us, “No one knows better how to cover tracks and remove incriminating evidence than a crime fiction writer.” I find the “A-ha! we caught her out!” tone of this comment rather distasteful. To incriminate means to accuse someone of a wrongful act — surely HarperCollins did not mean to take the position that lesbianism is “wrongful.”

Be that as it may, Drayton writes more in depth about a life-long female friend of Marsh’s, Sylvia Fox, than did Lewis, who only mentioned Fox sporadically. Drayton says she left the matter of whether Fox and Marsh had a lesbian relationship for readers to decide, though I think it’s pretty clear from her book that she implies that they did.

The two women apparently took several trips together. Fox in 1963, when both women were in their late sixties, moved to a cottage that neighbored Marsh’s and a path was cut though a hedge so that they could conveniently visit each other.

When Marsh was nearing death she destroyed a lot of papers (that “incriminating” evidence?). When Fox died a decade after Marsh, her headstone was placed beside Marsh’s. “They were the closest of friends, companions and neighbours in life and will be for eternity,” Drayton concludes. (This is even the concluding line of the book.)

I had always wondered myself whether Marsh might have been a lesbian. I suppose Drayton’s book moves the ball somewhat in that direction; yet Marsh “always” denied she was a lesbian, according to Drayton and it’s certainly possible that the two women may merely have been close friends. Who knows?

The larger problem with Drayton’s book as a biography is that it never really gets us any closer to the personality of the woman than Lewis’s. (Indeed, Lewis may have been a bit better here.) Marsh was a very guarded person and thus a tough nut to crack in a biography.

Lesbianism does not seem to have been a theme of Marsh’s books, even implicitly. (There is a lesbian character in Singing in the Shrouds, whom, oddly, Drayton does not discuss.)

Gay men appear in her books, invariably, as I recall, as stereotypical “queen” types — amusing up to a point, but hardly different from conventional portrayals. In contrast with Mary Fitt, who definitely was a lesbian, and Gladys Mitchell, who has been said to have been one, I do not really get that “feel” from Marsh’s books.

Thus, while the matter of Marsh’s sexuality probably at this late date will never be resolved, I’m not sure how relevant it is to her analyses of her work anyway.

So, should you buy this book? If you have the Lewis already, I’d say it’s a judgment call. On the whole, I would say Drayton’s is the more interesting work, but the Lewis has some points in its favor as well. Meanwhile, there’s still room for a really definitive critical study of the woman’s book on crime, which to me are even more interesting than her “life in crime.”

Tue 3 Aug 2010

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE NIGHT HORSEMEN. Fox Film Corporation, 1921. Tom Mix, Mae Hopkins, Joseph Bennett, Sid Jordan, Bert Sprotte, Cap Anderson. Based on the novel The Night Horseman, by Max Brand (Putnam, 1920). Director: Lynn Reynolds. Shown at Cinecon 27, Hollywood CA, September 1993.

Tom Mix plays Whistlin’ Dan Barry in this filming of a Max Brand novel, a somewhat bizarre tale of a cowpoke who follows the flight of the geese and whose eyes turn yellow when he’s angry.

His code would keep him away from the dying rancher who raised him and drive him to kill the rancher’s son whom he seems to love like a brother. Dan crosses the meanest man in the county by killing his brother, and their battle, along with Dan’s reconciliation with the rancher’s son and the gal who loves him, made for an exciting, satisfying wind-up.

Tue 3 Aug 2010

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

SUSANNE ALLEYN – A Treasury of Regrets. St.Martin’s Press, hardcover, April 2007.

Genre: Historical mystery. Leading character: Aristide Ravel; 4th in series; 2nd published (see below). Setting: France, 1797.

First Sentence: Since the twenty-fourth of Frimaire, Aristide Ravel had dreamed at least a dozen times of the guillotine.

It begins with the poisoning death of Martin Dupont, the controlling head of a large household. A servant girl, Jeannette Moineau, is arrested. A member of the house, Laurence, asks the police for help as she does not believe the girl is guilty.

Police investigator Aristide Ravel agrees to work with her, also discovering there is another link between them from the past. As others die, Ravel continues to search for motive believing if he finds the motive, he’ll find the killer.

Ms. Alleyn does know how to bring post-Revolution Paris alive. Best of all, we come to know the period from the characters; their memories, the awkwardness in speech tying to confirm to the new forms of address, the new calendar and the challenges living day-to-day. It is enough past the Revolution that there is not the high level of fear, but recent enough that you sense people’s uncertainty.

Aristide is a complex and interesting character, but although his back story was provided, he never really came to life. In spite of the personal connection between him and Laurence, I sensed no chemistry or emotional connection. Even at the end, rather than being left with a sense of curiosity, I found I didn’t particularly need to know what happens. For the other characters, perhaps because there were so many of them, none of them were well developed.

The story has a very powerful opening. Fascinating information is provided on the different figures involved in the Revolution, and the impact on the monetary structure. The plot, however, was very slow until about half-way through. As we progressed, I felt there was a rather too convenient twist and huge leaps in logic made to bring us to the proper conclusions.

In spite of the positive elements, and there were some, I did not find this book as engrossing as the previous books in the series. Had this been the first book I’d read of this series, I might not read another.

Fortunately, I have read the other two books published so far, and I loved them. I have great hopes that the next book will restore my faith in this author.

Rating: Okay.

The Aristide Ravel series:

1. Game of Patience (2006) [Book Three; 1796]

2. A Treasury of Regrets (2007) [Book Four; 1797]

3. The Cavalier of the Apocalypse (2009) [Book One; 1786]

4. Palace of Justice (2010) [Book Two; 1793]

Tue 3 Aug 2010

Con Report: PULPFEST 2010

by Walker Martin

I’m just recently back from one of the most enjoyable four days in my life as a collector. It’s true. I only got four hours of sleep each night and I ate and drank beer to excess, but I hung out with the greatest group of collectors and happily wallowed in a sea of pulps, books, vintage paperbacks, and original pulp art paintings.

Since I was going to leave for the convention on Thursday, I started to pack up on Wednesday the pulps that I was going to sell at my table. As I sorted through the hundreds of issues I came to the horrifying realization that I simply could not bear to part with any of them, so I put them back on the shelves and decided to just sell canceled checks from the Popular Publications and Munsey files and a box of DVDs. As usual the checks sold well.

The last few years I’ve driven out to the pulp conventions with Steve Kennedy, a NYC art dealer who is a not an early riser. Thursday morning at 5:00 am, I began the usual ordeal of getting Steve out of bed and into the car so that we could be on the road by 6:00.

Nine hours and 500 miles later we arrived at the Columbus, Ohio Ramada. Though it was only 3:00 pm, pulp collectors were already showing up and several rang my room to see when we could all get together. Within a couple hours, several of us were chowing down the hotel restaurant food.

I’ve heard several complaints about the hotel food and the lack of restaurants within walking distance. Frankly, I don’t care if the food or restaurants are good, bad, or indifferent. I’m there for the books, pulps, and artwork.

Most mornings I ate breakfast in the hotel with such crazy collectors and longtime friends as Scott Hartshorne, Nick Certo, Dave Scroggs, Ed Hulse, and Digges La Touche. The one breakfast that we ate at the Waffle House, I made the interesting discovery that Lollipops, The Gentlemen’s Club was next door. Some of us were going to visit to see if any of the girls were pulp collectors, but there was a Shriners convention also at the hotel and these guys were real party animals without the distraction of books and pulps. Maybe next year…

The hotel was a real bargain and despite the lack of nearby restaurants, I’ve never seen room rates so low for a hotel which also provided a large dealer’s room, hospitality suite, and meeting rooms. In fact the lack of restaurants is not really a problem at all because the hotel has a nice 15 person shuttle van that will take you and pick you up from any place in town.

The Hospitality room was excellent, full of beer, soda, and snacks. Also full of knowledgeable collectors talking about pulps into the early morning hours. I would like to thank the great guys who are responsible for stocking the beer. I’m very thirsty after a long day of breathing in pulp chips and talking about the joys of collecting to just about anyone who would stand still.

The dealer’s room this year was far larger than last year’s room with a lot of space between dealers. The attendance was even better that last year’s 350, reaching at least the 390 mark. This attendance of almost 400 is more than any that the old Pulpcons ever had.

I would place this year’s show as one of the very best I’ve ever attended, and I’ve been to almost all since the first one in 1972. I rank the 2010 PulpFest with the first Pulpcon in 1972 and the 1981 Cherry Hill event, where I scored over 10 pulp cover paintings for an average price of $200 to $400 each.

So many great collectors were there that I cannot mention them all. But I will mention two who have excellent blogs and websites that often mention pulps and paperbacks: Laurie Powers of Laurie’s Wild West and of course Steve Lewis of Mystery*File. Besides the PulpMags Yahoo group, these are the only two websites I make a point of visiting every day.

The evening panels were the best I’ve ever attended, though the Windy City Adventure panel was also outstanding. Friday night we had a panel on The Pulp Western with Guest of Honor William Nolan, Mike Nevins, Don Hutchinson, Laurie Powers, and Ed Hulse.

This type of panel never happened before because of the constant emphasis on such subjects as the hero pulps. Westerns once were extremely popular and were outsold only by the love pulps, so we need more discussions concerning the western pulps.

Also on Friday we heard William Nolan’s speech, Stephen Haffner on Leigh Brackett, and Tony Tollin on his favorite subject, The Shadow. During the day, I couldn’t drag myself away from the joys of the dealer’s room but I’ve been told that Mike Nevins gave an interesting talk concerning his new book, Cornucopia of Crime.

I managed to get an advance copy signed by Mike and can report it is a major publication, collecting many of his essays on mystery authors that he has written over the years.

As good as Friday was, Saturday was even better, with the business meeting, Munsey Award presentation, Black Mask panel, and the auction.

The Munsey Award was properly awarded to Mike Chomko but I didn’t hear presenter Tom Roberts mention why Mike was getting the award. Not only has he been one of the major members of the PulpFest committee (the others are Jack Cullers, Barry Traylor, and Ed Hulse), but he used to publish one of the very best of the pulp fanzines, Purple Prose.

It was a major disappointment when Mike had to suspend the magazine due to his medical studies and I tried to talk him out of it to no avail. Hopefully he will find the time to revive this great magazine. In addition he is the major dealer of pulp related books, selling just about every pulp reprint that’s available. We haven’t had such a dealer since the great old days of Robert Weinberg Books. Congratulations Mike.

The Black Mask panel ranks as one of the very best panels, right up there with the great Adventure panel at Windy City. During an hour Bill Nolan, Ed Hulse, John Wooley, and I managed to discuss every major period of the magazine and many of the writers and editors

Bill Nolan talked about the Joe Shaw years of 1926-1936 when the very best in hard boiled fiction was published; Ed Hulse covered an over view of the magazine and discussed the Fanny Ellsworth years of 1937-1940; I talked about the Ken White years in the forties and John Wooley discussed the post war period.

We also covered just about every major writer such as Hammett, Chandler, Carroll John Daly, Horace McCoy, Fred Nebel, Raoul Whitfield, Erle Stanley Gardner, Paul Cain, Merle Constiner, D. L. Champion, Robert Reeves, and Dale Clark, Butler, Norbert Davis, among others.

Perhaps many of the readers of this report will only recognize such famous names as Hammett, Chandler, Gardner, but believe me these other writers have been unjustly forgotten and some rank right up there with our favorite SF, western, adventure and mystery writers. I say “some” because we did have some critical things to say about Carroll John Daly and Horace McCoy.

The auction was very well attended and 142 lots went up for bids. Collectors managed to obtain such pulps as The Shadow, Golden Book, Frontier Stories, Western Story, Argosy, Popular, Thrilling Wonder, Adventure, Nick Carter, Pete Rice, Fantastic Adventures, Air War, Startling Stories, Captain Zero, Super Detective, Black Mask, Dime Detective, Detective Story, Flynn’s, Double Detective, Thrilling Adventures, Dime Mystery, G-8, Detective Tales, and many others.

The most interesting item was Walter Gibson’s typewriter, or at least one of them, with a letter of authenticity.

I obtained my usual pile of wants and interesting objects. I’m working on a complete set of Western Story, and I’m somewhere around the 1200 issue mark, so it’s getting very difficult to find the early issues I still need, but I found one from 1922.

I showed the issue to Laurie Powers and other collectors, and they must of thought I was crazy to be so happy about one issue of Western Story, but that’s the excitement you feel as you near the completion of a lifelong project.

Another find that impressed everyone was a 1940’s issue of Love Book. Normally you would think such a find to be of very little interest but over 30 years ago I obtained a love pulp cover painting showing a pretty girl typist smiling.

I’ve hunted decades for the magazine to go with the painting and had just about given up, thinking that I’d never locate the issue among the thousands of love pulps that were published. But at this convention while digging through rows of love pulps, I found not only the issue but a second one as well.

I proudly showed it to my pulp collecting pals who over the years had become bored with my constant whining about finding the love magazine to go with the painting. They will now be pleased to hear that now I will shut up about the subject.

I also obtained an original cover painting from Detective Fiction Weekly and an interesting piece of artwork showing the Yellow Peril danger of World War II.

John Locke’s Off Trail publications just put out an excellent two volume collection of Ghost Story fiction. It also contains a history of the magazine and original research on the writers. This is a must buy because the original magazines are so rare.

I bought several of Tom Roberts Black Dog Book reprints. I especially am looking forward to reading the first volume of the best of Adventure magazine, edited by Doug Ellis. Also the first three or four of the Talbot Mundy library are out.

We are living in the Golden Age of pulp reprints and I saw plenty of tables packed with reprints by Black Dog Books, John Locke’s Off Trails, Altus Books, Age of Aces, Girosal, Stephen Haffner’s books, and others.

The new issue of Blood n Thunder made its debut and it’s a stunner, perhaps the best issue yet, 100 pages long, containing a long article by Tom Krabacher about Gordon Young, an unjustly forgotten writer. The issue is a celebration of Adventure‘s 100th birthday and also contains pieces by Ed Hulse on the Lady Fulvia series, a serial based on a W.C. Tuttle novel, and an article by Adventure editor Arthur Sullivant Hoffman on writing for the pulps.

There is also a long section titled, “The Campfire: Sumer 2010 Edition.” Reading this section will point you toward some of the best fiction published in Adventure. It’s sort of a “My Favorite Issue” discussion by such collectors as Doug Ellis, Tom Krabacher, Dave Scroggs, Brian Taves, Ralph Grasso, Digges La Touche, Ed Hulse, and myself.

Many years ago Doug Ellis published one of the great magazines about the pulps, Pulp Vault. I had hoped that the new issue would finally be available at PulpFest but Doug gave me the sad news that it was delayed.

When this issue is finally published it will be the greatest issue of a magazine ever published about the pulps. I understand it will be over 200 pages with an unpublished Virgil Finlay cover and full of interesting articles such as Mike Ashley’s article on Blue Book, over 15,000 words long. Reader and Collectors, this will be an issue worth waiting for!

I know I’ve left a lot out and perhaps other attendees can contribute comments or correct any mistakes. I would like to thank the committee members for all their hard work on this convention. I’m referring to Mike Chomko, Jack Cullers and his family, Barry Traylor, and Ed Hulse.

Also thanks to Chris Kalb for his work, John Gunnison for his voice in the auction room, Tony Davis and others involved with The Pulpster, and the collectors who stocked the Hospitality suite.

Fellow readers and collectors, this is not a convention to be missed. Start making plans for next year because we have to support this event with our attendance. If it wasn’t for these people, by now we would mourning the death of the summer convention, because the old Pulpcon was on its last legs.

Tue 3 Aug 2010

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

MICHAEL ATKINSON – Hemingway Cutthroat. St. Martin’s, hardcover, July 2010.

The only thing that was any good was what you made up, what you imagined.

At about the same time Jose Robles Pazos was murdered, Ernest Hemingway was drunk on sangria. He would soon become a hunted man, and of course it was the sangria’s fault.

Ernest Hemingway, fresh to Spanish shores to write about and participate in the Spanish Civil War is …

… in Spain for only three days and looking for old-fashioned trouble, (he) had lost all his pocket money because he never quite fathomed the game (Mus), which smelled like poker but kept involving bridge like partnerships …

A good start for Michael Atkinson’s second darkly humorous mystery (following Hemingway Deadlights, 2009) to feature a somewhat bemused Papa Hemingway as reluctant sleuth.

Though Hemingway (and especially that famous lost suitcase and missing novel of his) has featured in mystery and suspense novels before (notably by Bill Granger and Dan Simmons), Atkinson has taken a unique turn eschewing any attempt to recreate the Hemingway style or voice while managing to suggest it whenever he puts us in Hemingway’s mind, and taking a decidedly cock-eyed look at the author’s famous machismo without parodying or laughing at it.

After being skinned in a game of Mus and participating in a bullfight in a Madrid basement Hemingway finds himself trying to uncover who murdered Pazos, a bureaucrat in the Popular Front and an old pal of Papa’s from the First World War, and accompanied by his friend and literary rival John Dos Passos. [FOOTNOTE]

Murder novels set in wartime settings can be tricky things, and amid the Spanish Civil War — a rehearsal for the Second World War with the Nazis on the Royalist side and Stalin and much of the West on the Republican side — the fate of one man amid so much slaughter is a tough sell, but Atkinson manages to bring it off both thanks to his cranky sense of humor and a convincing, if offbeat, portrait of Hemingway as a boozing, brawling, but loyal friend who won’t let go short of uncovering the killers and the motive behind the death of Pazos.

And there are plenty of suspects on both sides. Spain in the Civil War was a treacherous place. Aside from the war the Republican side was haunted by Soviet purges designed to cover up their general incompetence against the Nazi blitzkrieg, and the hot blooded and violent nature of the people themselves.

Atkinson uses this as the basis of a good deal of grim humor and populates the novel with a collection of colorful types who complicate Hemingway’s investigation, including Dr. Florapedes Crespo, his friend Pazos mistress:

The damned woman had his tongue in knots. She was beautiful and smart and also possessed Robles air of unwavering rectitude. She was intimidating goddammit. Jesus, didn’t these people do anything wrong? Well, yes, they did — they had infidelities. That at least.

Hemingway may seem an unlikely sleuth, but he was a fan of both Dashiell Hammett (he wrote To Have and To Have Not largely as his ‘answer’ to what he perceived as the false idea that the tough guy was uniquely suited to survival that he thought was Hammett’s theme), and Raymond Chandler, and a champion of Georges Simenon and Maigret from his years in Paris where Gertrude Stein introduced him to the joys of the Maigret novels.

He may not be a particularly cerebral sleuth, but as a two-fisted investigator with trench coat and booze in hand he is well suited to the rough and tumble investigation style of Atkinson’s humorous and suspenseful novels, and his years as a crime reporter in Kansas City add a certain reality to the conceit of Hemingway as detective.

Hemingway soon puts the pieces together and finds himself both hunter and hunted as he puts together the story of Pazos death at risk to life limb and the few illusions he has left until an effecting, ironic, and surprisingly powerful conclusion:

I should be sickened or shocked, thought Hemingway. Demoralized, or haunted by images of suffering, of modern men doing this to each other, with tools, that you can read about in Dante.

But he wasn’t, and he wasn’t satisfied or anything like it either. He was merely caught by the sentence he’d been writing, which was about killings and bad memories, and he could hear the heart pulse of it better in his head now, better than before. Hemingway went back to it, pencil to paper, quickly because he didn’t want it to escape. When it rolled further, by its own steam, he smiled. Where he was in that sentence, it was vicious and dark, but it was better than where he was. It was safe, it had balance, and it was his.

It is one of the few times Atkinson apes the Hemingway voice to any extent, and he gets it right and at the right time, and in the right place, and for the right reason.

I’ll look for Atkinson’s first novel and keep an eye out for later books that may emerge, whether they feature Papa Hemingway as sleuth or not. Atkinson has a good ear for dark humor and even a touch of slapstick, and in this relatively short and suspenseful book has produced a good evocation not only of Hemingway, but of the dark and terrible price of a modern yet ancient land in wartime.

[FOOTNOTE] The novel makes a good deal of the debate between Hemingway and Dos Passos on the subject of experience versus imagination in a work of fiction, and while it is true Hemingway set out to experience the things he would write about, he also wrote in the Nick Adams story, “On Writing” (also quoted above):

“Everything he’d ever written that was any good, he’d made up. None of it ever happened. Other things happened. Better things maybe. That was what the family couldn’t understand. They thought it was all experience.”

« Previous Page — Next Page »