June 2011

Monthly Archive

Sun 12 Jun 2011

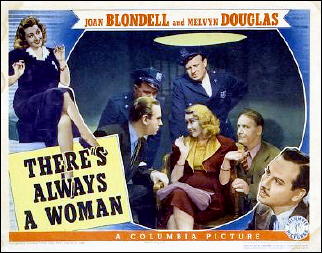

THERE’S ALWAYS A WOMAN. Columbia Pictures, 1938. Joan Blondell, Melvyn Douglas, Mary Astor, Frances Drake, Jerome Cowan, Thurston Hall, Walter Kingsford, Lester Matthews. Screenplay: Gladys Lehman, based on the short story “There’s Always a Woman” by Wilson Collison (American Magazine, Jan 1937). Director: Alexander Hall.

A disappointment. After the success of The Thin Man in 1934, there were any number of attempts by Hollywood to cash in on its success, and There’s Always a Woman was one of them.

Woman, in fact, was intended to be the first in a long series of adventures of PI Bill Reardon (Melvyn Douglas) and his daffy wife Sally (Joan Blondell), but there was only one followup and no more. (I’ll get back to that later.)

After quitting his job with the D.A.’s office, Bill Reardon starts up his own private eye agency, but business is so bad and in spite of his wife Sally’s encouragement to stick it out a while longer, he decides to stop beating the dead horse and go back to work for the D.A.

Of course, no sooner does he go out the door but a client walks in. A wealthy society lady (Mary Astor) has a task for the Reardon Agency: to find out if her husband is having an affair with his former paramour, now engaged to another man.

Sally, you will not be surprised to learn, accepts the case, and not so incidentally, the three hundred dollar retainer that goes with it. (Three hundred dollars paid for a lot of groceries in 1938.)

When the husband gets murdered, the game is on, but good. Sally is determined to solve the case on her own, while Bill on his part has all the resources of the D.A. (Thurston Hall) for whom he’s now working.

While it’s a decent enough murder mystery, many viewers may not even notice. What this movie really is is a screwball comedy all the way, with all the stops let out and the battling Reardons in fierce competition from beginning to end – if not all out war.

And here’s where we came in, and where I begin to quibble and shuffle my feet a little. To my mind, the Reardons are far too antagonistic and aggressive in their struggle to outdo the other, and when I say aggressive, I mean physically.

There are one or two times when Bill Reardon appears all but certain to rear back and give Sally a punch, and once, after a yank on Sally’s hair that’s a little too fierce, there is a glare in Joan Blondell’s eye in return that definitely does not speak of love.

It’s been quite a few years from 1938 to now, and I wonder if bringing up today’s attitudes toward spousal abuse as opposed to almost 75 years ago is a point worth mentioning. But while there are scenes in this movie that are funny – how could there not, with bright and sassy Joan Blondell in one of the two primary roles? – most of the humor seems a little too forced for me to give you the full thumbs-up for it which, given the two leading stars, I entirely expected to.

There was a second movie in the series, There’s That Woman Again, made in 1939, but while Melvyn Douglas returns, Joan Blondell did not; Virginia Bruce played Sally in the sequel. I’ve located a copy, and a look at the second installment of the series will be in order when it arrives.

Sun 12 Jun 2011

THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by MONTE HERRIDGE

#4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

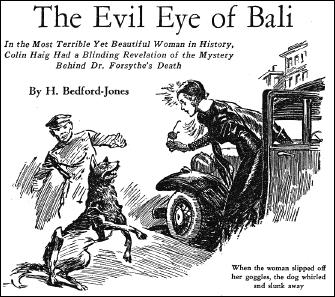

The Colin Haig stories by H. Bedford-Jones made up a short-run series of six stories published consecutively from the October 7, 1933 issue through the November 11 issue. The stories are narrated by Martin Burke, who is the assistant in charge of Colin Haig’s laboratory in Los Angeles, “unequaled in the country.â€

The series relates the adventures of Colin Haig and his assistant against a priestess of Shiva named Madame Vanderdonk. She is supposedly the possessor of an evil eye, which can kill people and animals. This power is shown in the first story in the series, “The Evil Eye of Bali,†and Colin Haig cannot get anyone to believe him when he relates this fact. However, she has criminal agents who seem to do most of the actual killing by various means.

I am missing the second story in the series, “The Desert of Death,†but “The Backward Swastika†is the third story, and involves more of the struggle against Madame Vanderdonk. Lieutenant Kelly of the missing persons detail of the local police makes an appearance at the beginning of the story, relating what they know about Madame Vanderdonk’s activities.

It appears that she is targeting wealthy financiers, stealing their money and causing their deaths. The police have counted ten victims so far, and Kelly tells of a possible eleventh victim named Johansen. Kelly relates all of this information to Burke; Haig has been gone for three days looking for a trail to follow to Madame Vanderdonk based on photographic evidence acquired in the second story.

Charles Hunter, one of Madame Vanderdonk’s murderous agents, appears for the first time in this story and uses a fake Haig letter to lure Burke into a trap, where he finds Johansen. He also meets Madame Vanderdonk, who talks to him. She attempts to manipulate him, but it doesn’t work, as Haig and Lieutenant Kelly arrive in time to rescue the two men. Madame Vanderdonk flees in her car.

In the fourth story, “Circles of Doom,†Burke receives a telephone call from a Professor Malvolio, whose real name is Van Steen. He is a professional hypnotist. Van Steen is asking for information about Madame Vanderdonk. He promises to come and see Colin Haig, but never arrives. He then calls Haig and asks him to come to see him.

Haig arrives to find Van Steen dead by means of poison and Van Steen’s daughter present. Haig and his assistant, with the aid of the police (including Lieutenant Kelly), investigate the situation and discover much information, including a good deal about one of their nemesis’s agents, Charles Hunter (first seen in the third story).

However, Hunter is dead from an accident by poisoning by the time they reach him. Another dead end for Haig, but he has an idea she has her headquarters is in the desert around Palm Springs, and plans to search for her.

The fifth story, “Footsteps of Death,†opens with Lieutenant Kelly saying he can’t help them in their fight against Madame Vanderdonk outside the city limits of Los Angeles. His superiors don’t believe in the evil eye.

Shortly thereafter, another attempt is made upon the lives of Colin Haig and Martin Burke. This impels them to immediately start the search for Madame Vanderdonk’s desert lair. After searching in the heat for quite a while, they stumble upon a dying man whose last words indicate he knows the woman for whom they are searching.

They then search outward from that spot. Martin Burke finds woman’s hideout and is captured. He undergoes another session with Madame Vanderdonk as she attempts to win him over to her cause. He soon escapes, and finds Colin Haig nearby.

Haig wants to go for help and return to attack the dwelling. Somehow, to me this sounds too simple to expect her to stay there and wait for him to return. On to the final part of the story.

In the sixth and last story in the series, “The Niche of Horror,†Colin Haig manages to get himself captured by Madame Vanderdonk. With this series, it was only a matter of time. He manages to escape the evil eye of the madame by sabotaging her base of operations and ending her reign of terror.

This quick, short series of stories did not leave much time for readers to have to wait for each installment in the ongoing story. With the series preplanned and an ending provided, I don’t see why there wasn’t a sequel to it. That is, assuming the series was well received by the readers. It had plenty of action.

The Colin Haig series by H. Bedford-Jones:

The Evil Eye of Bali October 7, 1933

The Desert of Death October 14, 1933

The Backward Swastika October 21, 1933

Circles of Doom October 28, 1933

Footsteps of Death November 4, 1933

The Niche of Horror November 11, 1933

Sat 11 Jun 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

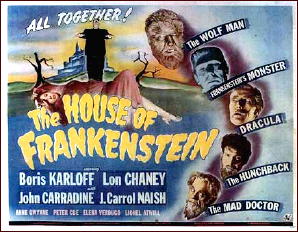

HOUSE OF FRANKENSTEIN. Universal, 1944. Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, John Carradine, J. Carrol Naish, Elena Verdugo, Glenn Strange, Anne Gwynne, Peter Coe, Lionel Atwill, George Zucco, Sig Ruman. Screenplay by Edward T. Lowe, from a story by Curt Siodmak; Jack Pierce, makeup; Hans Salter, music; George Robinson, photography. Director: Erle C. Kenton. Shown at Cinecon 44, Hollywood CA, Aug-Sept 2008.

This film is neither rare nor one of the great Universal horror films. It was scheduled for the convention appearance of Elena Verdugo, who played a gypsy girl, but is probably best remembered for her role as the office nurse on the long-running Dr. Welby TV series that starred Robert Young.

However, the opportunity to see the cast that included almost all of the major (and minor) actors in the Universal horror films in a 35mm print was something of a treat. Karloff is a doctor who wants to revive the Frankenstein monster, Chaney reprises his famous role as the Wolfman, Carradine makes an honorable stab at Dracula, and Glenn Strange plays the Monster, with J. Carrol Naish as the hunchback assistant to Karloff who has promised to transplant his brain into a young, handsome body in return for his services.

The film isn’t scary, but it’s handsomely produced, and Verdugo talked prettily about her career after the screening, although nothing particularly memorable came to light.

Sat 11 Jun 2011

WHO WAS ARTHUR MALLORY?

A 76-Year Old Pseudonym Revealed

by Victor A. Berch

In a recent exchange of e-mails with my colleague, Allen J. Hubin, he queried me about the death date of the author known simply as Arthur Mallory.

Mallory’s entry in Allen’s Crime Fiction IV appears as follows:

MALLORY, ARTHUR. 1881- ?

The House of Carson (n.) Chelsea 1927

Doctor Krook (n.) Chelsea 1929

The Fiery Serpent (n.) Chelsea 1929

Apperson’s Folly (n.) Chelsea 1930 [Dr. Kirke Montgomery; New York]

The Black Valley Murders (n.) Chelsea 1930 [Dr. Kirke Montgomery; New York]

Mysteries of Black Valley (n.) Chelsea 1930 [Dr. Kirke Montgomery; New York]

The FictionMags Index adds a little more biographical information about Mallory, specifically that he was born on a ship in the Indian Ocean, along with a list of stories he wrote for Breezy Stories and Detective Story Magazine. No more than a dozen of these are listed, but the connection of Chelsea House and Detective Story is not surprising, since the former was the hardcover imprint of Street & Smith, which also published many pulp magazines, including DSM.

However, I had no idea how much truth there was in that piece of biographical information from FictionMags, so I set out to discover what might be in the Ancestry.com genealogical database.

There were some Arthur Mallorys, but none that fit the date of birth nor the description of the author. Searching further however, the name Arthur Mallory popped up in an obituary in the New York Times as the pseudonym of Ernest M. Poate, a mystery writer of some note.

The obituary, which was dated Feb. 3, 1935, also provided the following information: Dr. Poate was born in Yokohama Japan and died in Southern Pines, North Carolina, Feb. 1, 1935, at the relatively young age of 50. He was a physician and an attorney as well as an author.

Checking out entry for Poate in CFIV, I found the following:

POATE, ERNEST M. 1884-1935.

The Trouble at Pinelands (n.) Chelsea 1922 [North Carolina]

Behind Locked Doors (n.) Chelsea 1923 [Dr. Thaddeus Bentiron; New York City, NY]

Pledged to the Dead (n.) Chelsea 1925

Doctor Bentiron: Detective (co) Chelsea 1930 [New York City, NY]

Murder on the Brain (n.) Chelsea 1930 [New York City, NY]

The first thing one notices is that Mallory and Poate had the same publisher, and digging a little further it can be discovered that the stories in the Dr. Bentiron collection were reprinted from Detective Story Magazine.

The other major match between Mallory and Poate is that both used doctors as main characters in many of their books. This had to be more than coincidence. Just as the Times obituary had stated, and in spite of the discrepancy between the two dates of birth (and the location), the two men were one and the same.

Poking around a bit more, I learned that his parents were Thomas Pratt Poate and Belle (Marsh) Poate, missionaries in Japan until the family immigrated to the US in 1892. His birth mother had died in 1896 and by 1900, his father had remarried. His World War I draft registration revealed that he was born October 10, 1884 and his full name was Ernest Marsh Poate.

Anyone wishing to dig further into the family can examine the Poate family papers housed at Cornell University Library. The basic information on Dr. Poate will appear in the next Addendum to Crime Fiction IV.

— Copyright 2011 Victor A. Berch

Thu 9 Jun 2011

WE ARE ALL SENTIMENTALISTS NOW:

Leonard Cassuto’s Hard-Boiled Sentimentality:

The Secret History of American Crime Stories

by Curt J. Evans

Over the last twenty years feminist literary scholars have leaped into the field of mystery criticism with great energy and enthusiasm; and they have had a remarkable impact on it. In Great Britain, such academic authorities as Gill Plain, Susan Rowland and Merja Makinen have written perceptive revisionist studies on British Golden Age “Crime Queens†(Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Margery Allingham and Ngaio Marsh), defending them from the traditional (usually male) criticism, dating back to Raymond Chandler and Edmund Wilson in the 1940s and prevalent through the early Marxist-influenced academic monographs of the 1970s, that their work is insipid, reactionary drivel, in contrast with the admirable, socially progressive and genre transcending American hard-boiled fiction most famously associated with Dashiell Hammett and Raymond Chandler himself.

This scholarly feminist emphasis on the Crime Queens, while important in revising earlier masculinist views of these authors, has led to the elevation of an increasingly commonplace view within academia, namely that the mystery genre in Britain during the Golden Age was essentially feminine, representing a purportedly distinct and uniquely female set of values, such as the privileging of feelings and intuitions over material detail (i.e., psychology over footprints and timetables), a preference for cerebration over fisticuffs as the way of reaching solutions to problems and an emphasis on domestic detail and the inter-connectedness of individuals. “All in all,†emphatically concludes Susan Rowland in a representative statement from a recent essay, “the golden age form is a feminized one.â€

[Susan Rowland, “The ‘Classical’ Model of the Golden Age,†in Lee Horsley and Charles A. Rzepka, eds.,

A Companion to Crime Fiction (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 122.]

Thus portrayed, “feminine†English Golden Age detective fiction starkly contrasts with the “masculine†hardboiled form that frequently has been taken to represent American detective fiction during this period (roughly 1920 to 1939) — though the critical estimation of English Golden Age detective fiction (or, to be more precise, the four women authors often portrayed as nearly entirely representing it) has been considerably raised.

However, another feminist literary scholar — this time an American, Catherine Ross Nickerson — has pointed out in an important 1998 study, The Web of Iniquity: Early Detective Fiction by American Women, that detective fiction in the United States was not actually a strictly masculine preserve, a playground for the tough guys. Rather, Nickerson has shown, an indigenous American tradition of female-authored crime fiction existed well back into the nineteenth century.

One of the writers she discusses, Mary Roberts Rinehart, was active and extremely popular in the United States all though the Golden Age (indeed, she was much more significant at this time than Raymond Chandler, who only published his first novel in 1939, at the very tail-end of the Golden Age, confining himself before that to pulp short stories).

But although Professor Nickerson helped remind her academic colleagues that women mystery writers with their own narrative style and literary concerns not only existed but were much read in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s, it remained for Professor Leonard Cassuto to do something that no other academic had yet done: perceive the American hardboiled detective novel itself as feminized.

[Academic scholars continue to mostly overlook detective novelists in both the United States and Great Britain who did not write in the hardboiled style and were not women, but that is the subject for another essay!]

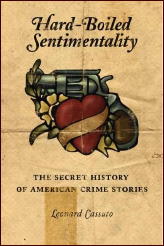

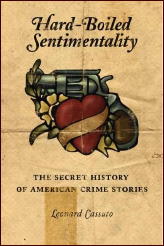

Leonard Cassuto’s Hard-Boiled Sentimentality: The Secret History of American Crime Stories (Columbia University Press, 2008) is one of the most highly praised academic crime literature monographs of the last decade. “Superb…fresh insights on every page,†declares Alan Trachtenberg of Yale University.

Not to be outdone is crime writer Julia Spencer-Fleming, who provides a blurb that is surely one to die for: “Hard-Boiled Sentimentality is a nonfiction epic that reads like the best genre fiction, tracing the bloodlines of crime fiction from Sam Spade to Hannibal Lecter. Cassuto’s scholarship is impeccable; his narrative voice magnetic. A must-read for every student of genre fiction and the go-to source for the evolutionary history of the genre.â€

Whew! Is it really as good as all that? In my view, not quite; though Cassuto makes an interesting (if not invariably persuasive) argument and his writing is comprehensible and refreshingly jargon-light, not something that can be said for many of the academic monographs in this field. Hard-Boiled Sentimentality often is quite insightful and for those interested in hardboiled fiction it should make rewarding reading.

[Despite the zealous claim that

Hard-Boiled Sentimentality reads as grippingly as the best crime novels, sentences like “this refusal to speculate aligns Spade with some of the reformist political positions of the Progressive era†do not trip off the tongue. To be fair to Cassuto, however, I cannot recall any academic monograph that reads just like a crime novel.]

Leonard Cassuto contends that rather than being “masculinist†tales of unfeeling lone tigers prowling in the asphalt jungle, hard-boiled novels in reality are closely related to women’s sentimental domestic fiction of the nineteenth century, which “celebrates the reliable and nourishing social ties that result when people extend their sympathy to others around them.â€

In Cassuto’s view, hard-boiled tales “engage with a domestic sentimentalism born of a specific historical period†and it is this “engagement with the nineteenth-century sentimental†that “shapes the history and evolution of the hard-boiled from its inception to the present day.†“Inside every crime story is a sentimental narrative that’s trying to come out,†declares Cassuto provocatively. “Sentimentalism invented the American crime novel.â€

Over the course of his study, which extends from the 1920s to the present day, Cassuto explicates the key role he sees sentimentalism as having played in the shaping of the American crime tale. Chapter One deals with the influence exercised on the hard-boiled school of crime writing by mainstream novelists Theodore Dreiser and Ernest Hemingway.

Chapter Two looks at Dashiell Hammett. Relying on his reading of The Maltese Falcon (and to a lesser extent Red Harvest and The Dain Curse), Cassuto argues that Hammett portrays “sentimentalism in ruins: a world of self-interested individuals cut loose from family ties and family obligations, who have abandoned sympathy to chase the dollar.â€

However he emphasizes that in The Maltese Falcon tough-as-nails detective Sam Spade struggles between “self-interest and sympathy†and that in The Dain Curse the Continental Op “shows genuine concern for his young charge [Gabrielle Leggett].â€

Chapter Three sees Cassuto taking on “Depression Domesticity,†primarily through James M. Cain’s Mildred Pierce and Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep and The High Window.

With its family saga of a deluded mother and her deceiving daughter, writes Cassuto, Mildred Pierce allows James M. Cain to bring “the sentimental and the hard-boiled into the same house.†It offers readers “the key to the hard-boiled engine-room.â€

Chandler’s detective Philip Marlowe, for his part, is in Cassuto’s view driven primarily by a need to put broken houses back together, restoring families to that portion of harmony still possible in 1930s America. As an author, asserts Cassuto, Chandler was “in quixotic pursuit of a family ideal that was being threatened during the Depression, when financial hardship broke many families apart.â€

Chapter Four, which takes us past World War Two and into the 1950s and the Cold War, sees Cassuto considerably expanding his analytical net, taking in a wider range of novels, including those by Chandler, Mickey Spillane, David Goodis, John D. MacDonald, William P. McGivern, Wade Miller, “John Evans†(Howard Browne), Gil Brewer and Cornell Woolrich.

“Working from the model provided by Raymond Chandler,†explains Cassuto, “postwar crimefighters become passionate and involved defenders of home and hearth.†Cold War paranoia and the desire to restore traditional gender roles after global conflagration had menaced world order combined to create the fetching but fearsome femme fatale, a creature in Cassuto’s view that is most notable for her refusal to accept what was seen as her natural role in the social order, that of domesticated wife and mother.

“A veritable army of unpredictable femmes fatales, armed and dangerous and set to destroy home and community, swarms out of the crime stories of the 1950s,†Cassuto writes colorfully. He is especially interesting here on the hard-boiled novel’s treatment of lesbians and transsexuals, who represented the ultimate in “female†transgression.

Even Cassuto’s creativity at finding sentimentality in every hard-boiled cavity he searches is stymied by those deviant and demented darlings of modern critics, Patricia Highsmith and Jim Thompson, however; and in Chapter Five, “Sentimental Perversion,†he shows how these compellingly idiosyncratic authors subversively undermined sentimentalism at every opportunity.

To be sure, sentimentality makes a considerable comeback in Chapter Six, where Cassuto looks at the work of Ross Macdonald, John D. MacDonald and (to a much lesser extent) Robert B. Parker. Anyone familiar with Ross Macdonald’s novels knows they changed over time, as Macdonald shook off the influence of Chandler (who was quite cutting in his appraisal of the younger man’s work) and allowed his own personal preoccupations to take hold of his narratives.

Making use of Tom Nolan’s fine biography of Macdonald, Cassuto is able to show how the author’s family problems meshed with the therapeutic culture of the 1960s to lead Macdonald to produce book after book on household dysfunction and the generation gap, with Macdonald’s series detective, Lew Archer, acting as a sort of family therapist (or as Cassuto writes, “a kind of walking vessel for collective guilt†and “an everyman of sympathyâ€).

For Cassuto Ross Macdonald “stands as perhaps the most sentimental of all hard-boiled novelists because he understands family ties in the same way the sentimental writers did a century before him.†Similarly, Cassuto believes the robust if offbeat home life (aboard a Fort Lauderdale houseboat called the Busted Flush) of John D. MacDonald’s detective Travis McGee firmly affiliates this author’s work with the sentimental side of life, since his detective is not office-centered like Sam Spade and Philip Marlowe.

Dealing with, respectively, female private eyes and race in the hard-boiled novel, Chapter Seven and Eight feel somewhat tacked on, but Cassuto returns in full force with a discussion of the serial killer and the crime novel in his monograph’s final chapter. Contrary to what we might think, serial killer novels also reflect sentimentalist hegemony, according to Cassuto. The serial killer should be understood as “an anti-family man,†Cassuto declares. “He is purely anti-sympathy, anti-domesticity, anti-sentimentality.†And opposing him is the increasingly sensitive and domesticated detective.

At one point in his book, Cassuto forcefully criticizes scholars’ “static and stereotyped conception of hard-boiled masculinity.†He rightly notes that this conception has arisen to a great extent from ingenuous readings of Raymond Chandler’s polemical 1946 essay, “The Simple Art of Murder,†which stridently emphasizes the tough masculinity of hard-boiled heroes by “feminizing the genteel detective story tradition.â€

To be sure, other critics before Cassuto have discerned a certain amount of hollow chest-beating bravado in Chandler’s essay. The great centenarian scholar Jacques Barzun, for example, noted forty years ago in the introduction to his and Wendell Hertig Taylor’s A Catalogue of Crime (Harper & Row, 1971) that Chandler in notable ways was himself a “sentimental [emphasis added] tale spinner†(p.11), whatever claims he made to the contrary in “The Simple Art of Murder.â€

Still, in forcefully challenging the “static and stereotyped conception of hard-boiled masculinity†with his lengthy study Cassuto deserves our praise. Nevertheless, I think that his admirable zeal to revise error sometimes pushes Cassuto to overstate his case, rendering an over-sentimentalized (or overly-feminized) interpretation of the hard-boiled crime novel.

Cassuto’s coverage of hard-boiled fiction in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s is sparser than I would have expected from an author advancing such an ambitious, overarching thesis. A number of significant tough crime writers of the period are short-shrifted (Raoul Whitfield) or ignored entirely (Jonathan Latimer).

Despite his fine discussion of Mildred Pierce, never does Cassuto convince me that James M. Cain’s admired novel truly is “the key to the hard-boiled engine room†(on the other hand, it is the work that most strongly supports his thesis). Does Mildred Pierce unlock Jonathan’s Latimer scabrously humorous The Lady in the Morgue (its repertoire includes necrophilia jokes about the lady missing from the morgue), for example?

While Cassuto provides some analysis of how James M. Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice and Double Indemnity (as well as Horace McCoy’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?) fit into his thematic structure, he largely omits consideration of the short stories of Hammett and Chandler, as well as Hammett’s novels The Glass Key and The Thin Man and Chandler’s novels Farewell, My Lovely, The Lady in the Lake and The Little Sister. (Playback is not here either, but who can really complain about that.)

These are significant omissions when one considers the small output of novels from the hard-boiled twin titans. In his entry on the novel in 1001 Midnights, Francis M. Nevins has written of The Glass Key that “its third-person narrative voice … is so objectively realistic and passionlessly impersonal that it seems to draw an impenetrable shield between character and reader.â€

Does Cassuto find sympathy in The Glass Key? In regard to Chandler, are his novels Farewell, My Lovely and The Lake in the Lake, published about the same time as The Big Sleep and The High Window, about Marlowe as a fixer of broken families? It would have been nice to see Cassuto’s thoughts on how these particular novels develop his themes.

[Bill Pronzini and Marcia Muller, eds.,

1001 Midnights: The Aficionado’s Guide to Mystery and Detective Fiction (Arbor House, 1986), 335.

In

Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, Chandler’s

The Big Sleep is discussed on a dozen pages,

The High Window on a half-dozen and

The Long Goodbye on three, while

Farewell, My Lovely is mentioned once (and this only in reference to its 1940s sales) and

The Lady in the Lake and

The Little Sister no times at all.

While doubtlessly

The High Window better illustrates Cassuto’s sentimental domesticity thesis than, say,

Farewell, My Lovely (where in my reading the strongest sentimental feelings are directed at single men),

The High Window certainly is not inherently a more “important†book in the Chandler canon than

Farewell, My Lovely. (Indeed, most critics clearly deem

Farewell, My Lovely to be markedly superior to

The High Window as a piece of literature.)

Similarly, Cassuto discusses Hammett’s

The Maltese Falcon on nearly thirty pages,

Red Harvest on seven and

The Dain Curse on six, while failing to mention the highly-praised

The Glass Key. Certainly

The Glass Key is considered a richer work than

The Dain Curse, which is almost universally regarded as Hammett’s poorest novel.]

Further, Cassuto’s attribution of causality for the way the narratives develop in the Hammett and Chandler novels he does write about sometimes is debatable. For example, Hammett’s vivid fictional world of grasping, self-interested and self-regarding individuals may owe more to the author’s engagement with Karl Marx than with Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Similarly, it seems to me that much of the thematic content in Chandler’s novels is derived from his marked resentment (personal, not ideological) of the idly wealthy and his deep sense of masculine honor. In my view, Marlowe’s sympathy in The Big Sleep is reserved for old General Sternwood, not his corrupted daughters.

Any repairing of the General’s home necessarily involves driving the insanely murderous and nymphomaniacal Carmen Sternwood from its precincts. (It is important to recall here the famous image of the stained-glass window in the Sternwood home depicting the knight battling the dragon, i.e., serpent — the serpent in the Sternwood home is Carmen, who even hisses at one point.)

As the critic Clive James has perceptively noted, “Carmen is the first in a long line of little witches that runs right through the [Chandler] novels, just as her big sister, Vivian, is the first in a long line of rich bitches who find that Marlowe is the only thing money can’t buy.â€

[Clive James, “Raymond Chandler,†in

As of this Writing: The Essential Essays, 1968-2002 (W. W. Norton, 2003), 204.]

Marlowe (who assuredly represents his creator) does not expend a lot of sentiment or sympathy either on the little witches or the rich bitches, those fallen temptresses and potential destroyers of men.

Certainly Chandler’s little witches are those les belle dames sans merci of hardboiled mystery, the femmes fatales (they appear — quite memorably — in Farewell, My Lovely and The Lady in the Lake as well, novels Cassuto does not discuss).

This fact alone leads me to question Cassuto’s assessment of the femme fatale primarily as a 1950s phenomenon. Cassuto himself admits that The Maltese Falcon offers a prominent example of the femme fatale, but the willful creature also rears her lovely head, as indicated above, numerous times in the works of Raymond Chandler, not to mention forties film noir, as well as other hard-boiled tales by the many 1940s writers not discussed by Cassuto.

Surely the explosion of the femme fatale phenomenon in this period was set off in part simply by the paperback revolution and the dramatic discovery that more explicit sexualization of women helped sell hardboiled books to male readers. In his book Hard-Boiled America, Geoffrey O’Brien perceptively highlights the impact of World War 2 in this context:

Wars in America have generally led to a relaxation of sexual censorship; for instance, the public acceptance of

Penthouse and

Hustler can probably be traced to the Vietnam War. Likewise the returning GIs of the 1940s craved stronger stuff than Betty Grable pinups…. With all the energy of an industry undergoing rapid development, the paperbacks — free of the constraints that hampered movies and radio — resolutely pushed the limits…. Encouraged by rising sales figures, [paperbacks] were no longer playing by the same rules (An illustrator whose career began in the postwar period recalls, “The word went out — get sex into it somehow.â€)

[Geoffrey O’Brien,

Hard-Boiled America (Da Capo Press, 1997) (expanded edition; originally published 1981).]

In short, sometimes hardboiled fiction surely engaged more directly with sexuality than sentimentality. (Certainly the lurid paperback covers did.) In Chandler’s case, the continual resort to the device of the femme fatale appears to have arisen more out of personal issues than national social and economic concerns (as does the distaste for homosexuals Chandler expresses though Marlowe in The Big Sleep), so once again Cassuto’s approach (e.g., traditional family rhetoric and the Cold War made them do it) seems overly mechanistic.

It should be noted that where it supports his thesis that a given hardboiled author is sentimental (Ross Macdonald in this case), Cassuto does resort in part to personal biography for answers as to why the author wrote as he did. Doing so makes his argument more persuasive (indeed, the Ross Macdonald section is one of the strongest in the book).

Sometimes Cassuto can be heavy-handed in his approach to causal factors. Could The Maltese Falcon or The Big Sleep have come into existence without Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, which observed the role self-interest played in guiding human endeavor, or his The Theory of Moral Sentiments, which analyzed sympathy?

Apparently they could not have, according to Cassuto. “Adam Smith may be considered the founding father of both sympathy and the hard-boiled attitude at the same time,†Cassuto rather breezily pronounces. “Smith published perhaps the foundational hard-boiled text, The Wealth of Nations, in 1776…. But Smith was already an expert on sympathy at the time he wrote his anatomy of capitalistic individualism; in 1759 he wrote The Theory of Moral Sentiments.â€

Such speculation led me idly to wonder how it is that Adam Smith never wrote a hardboiled crime novel. Had he done so, it inevitably would have been called, one imagines, The Invisible Hand.

[If Adam Smith is the “founding father†of sympathy, where does Jesus Christ fit into the picture?]

Despite these criticisms on my part, I think Cassuto has a valuable thesis overall. Academic analysts have tended to overly polarize male hard-boiled authors and female crime fiction writers (as well as traditional male detective novelists).

Thus I would recommend the perusal of Hard-Boiled Sentimentality by those interested in better understanding crime fiction. Yet I must also add a few more criticisms of the book that are of a different nature, stemming from Professor Cassuto’s evident lack of familiarity with the history of the mystery genre on certain points. (He is by no means alone among academic scholars in this regard.)

First, although he references Catherine Ross Nickerson’s The Web of Iniquity, rarely does Cassuto mention women crime writers before 1970 (Patricia Highsmith is the notable exception). In her review of Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, Sarah Weinman criticized Cassuto’s omission of Dorothy B. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place (1947) as “particularly startling†because “this novel seems to prove Cassuto’s thesis conclusively.â€

[Sarah Weinman, “Sentimental Tough Guys,â€

Los Angeles Times, 17 October 2008. Since in a footnote Cassuto briefly refers to the author’s handling of a serial killer in

In a Lonely Place, his failure to integrate the novel into the main body of his study clearly is deliberate, not inadvertent.]

I understand that Cassuto presumably wanted to focus on male hard-boiled writers rather than female ones, because the response to the inclusion of such a writer as Dorothy B. Hughes might well have provoked the response, “of course she wrote with sympathy, she was a woman!â€

Yet the omission of so many women writers does leave a sort of vacuum on those occasions when the author makes rather sweeping statements. When Cassuto writes that the “male heroes of most fifties crime novels … assume the protective role that women played in sentimental fiction of the previous century,†I could not help wondering what was going on in the fifties crime novels written by women. (In the works of women writers of 1950s “psychological suspense,†for example, one cannot always be sure of those “male heroes.â€)

Second, Cassuto, like most academic literary scholars, perpetuates the myth that Raymond Chandler cared nothing for plotting. In doing so he ironically relies mostly on Chandler’s “The Simple Art of Murder†essay, though elsewhere, as noted above, he chastises other scholars for unquestioningly accepting it. (He also digs up the old chestnut about Chandler not knowing who killed the chauffeur in The Big Sleep when questioned by Howard Hawks and William Faulkner, who were adapting the book to film).

Chandler “rejects the puzzle-whodunit because it’s unrealistic†and “turned away from the intricate plots of the likes of Ellery Queen and S. S. Van Dine because they’re too intellectual to activate the power of sympathy,†asserts Cassuto.

In a 2006 article in the Wall Street Journal, Cassuto is even blunter on this matter. “Raymond Chandler was the rare mystery writer who didn’t care whodunit,†Cassuto peremptorily pronounces in the first sentence of the article. Near the end of it, he asserts that “Chandler’s artistic impulse turns on his rejection of the puzzle mystery.â€

Though Cassuto is hardly alone in diminishing Chandler’s interest in the puzzle mystery (indeed, both Chandler’s biographers do it), he is wrong in doing so. Chandler read and enjoyed the traditionalist British detective novelists R. Austin Freeman and Freeman Wills Crofts (though he hated the debonair gentleman sleuths of the British Crime Queens and thought Agatha Christie was unfair to the reader), envied the plotting skill of Perry Mason creator Erle Stanley Gardner and composed, in the same decade as he wrote “The Simple Art of Murder,†a set of rules for writing mystery fiction that in many respects is as orthodox as those famously devised by Englishman Ronald Knox.

Further, for someone who purportedly “didn’t care whodunit†and rejected the puzzle mystery, Chandler perversely composed several well-plotted detective novels — praised by the orthodox critic Jacques Barzun — including Farewell, My Lovely, The High Window and The Lady in the Lake.

To be sure, The Big Sleep, his first mystery novel, does have, as scholars so often note, its share of plotting problems (I have never been too sure about that pesky chauffeur’s demise either); but that does not take away from the fact that several of his other novels are impeccably plotted. Chandler found plotting hard to do and groused about doing it, but he never rejected it and he often performed it admirably.

[Leonard Cassuto, “The Hero is Hard-Boiled,â€

Wall Street Journal, 26 August 2006. In his critical study

Raymond Chandler (Twyane, 1986), William Marling observes that Chandler’s novels after

The Big Sleep reveal the author’s “increased attention to plot.â€

He notes that Chandler “often came close to the ‘whodunit’ style of English mystery….than he cared to admit†(p. 104). For more on this subject see my forthcoming essay, “‘The Amateur Detective Just Won’t Do’: The Straight Dope on Raymond Chandler and British Detective Fiction.â€]

Third, Cassuto misunderstands the economics of book publishing in the years before the consummation of the paperback revolution. In Hard-Boiled Sentimentality, Cassuto describes The Big Sleep‘s selling of 12,500 copies as a “rocky debut.†(In his Wall Street Journal article, he earlier characterized such a sale as “meager.â€)

Riffing off this point, he concludes that the novel did not “find an audience†until 1943, when it was published in paperback and sold nearly a half-million copies. But in actuality, hardcover sales of a mystery novel title totaling to 12,500 copies was quite impressive in that era, a time when frugal people mostly borrowed mystery fiction (as opposed to “serious literatureâ€) from rental libraries.

Since presumably libraries purchased a great many of those 12,500 books sold, many thousands more than that number would have read the book in the four years that elapsed before The Big Sleep was published in paperback.

Finally, Cassuto’s references to the classical, puzzle-oriented detective novels of the Golden Age tend to be slighting and misinformed. Cassuto, who so forcefully critiques stereotype in the portrayal of hard-boiled fiction, tends himself to reach for stereotypes when using traditional detective fiction as a foil for the tough (yet tender) stuff.

“Hammett’s detective novels departed from genre tradition by presenting a story — and a set of social problems — unenclosed by a drawing room, a country estate, or any other discrete space,†writes Cassuto, relying on the well-worn but overstated notion that the narratives in traditional detective novels of the Golden Age are invariably confined within what are essentially enclosed stable spaces, usually country houses or villages.

Elsewhere, Cassuto passingly declares that hard-boiled novels “supplanted†puzzle-oriented Golden Age mysteries. While admittedly it is true that the rise of the hard-boiled school was one of the factors that helped break the puzzle’s hegemony over Golden Age crime literature, when (or even whether) hard-boiled tales “supplanted†puzzle mysteries is another question.

To state the most obvious example, the puzzle mysteries of Agatha Christie retain immense global popularity even today. Further, as stated above, the plots of many hardboiled novels in fact feature complicated puzzles. Novels like Raymond Chandler’s The Lady in the Lake or Jonathan Latimer’s The Dead Don’t Care have at their hard-boiled hearts fiendishly clever puzzle plots that would have graced even the diabolically ingenious tales of Agatha Christie and Ellery Queen.

All these matters aside, Cassuto has produced a worthwhile and interesting book. The splendid cover illustration of a steely gun and a beribboned red heart tells it all: the tough and the tender often manage to co-exist in the hardboiled novel.

Although Cassuto at times over-tenderizes the tough crime tale and I am not convinced that his engagement-with-domestic-sentimentalism thesis is the master-key that unlocks the hardboiled engine room (however much it helps reveal to us Mildred Pierce), I personally found in Hard-Boiled Sentimentality many fascinating points to engage me.

Wed 8 Jun 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

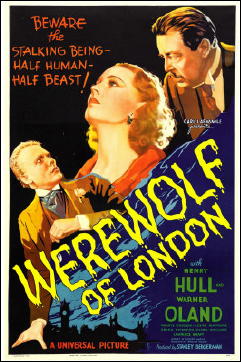

WEREWOLF OF LONDON. Universal Pictures, 1935. Henry Hull, Warner Oland, Valerie Hobson, Lester Matthews, Lawrence Grant, Spring Byington, Clark Williams. Director: Stuart Walker.

The Wolf Man, one of Universal’s strongest monsters — probably the appeal to teenage boys of a conflicted being who finds his body changing and getting hairy as his emotions run wild — only got one film to himself, The Wolf Man (1941).

For the rest of the run, he had to share the limelight with Frankenstein’s monster, Dracula and assorted mad doctors and hunchbacks, while second-string ghouls like the Creeper and Paula the Ape Woman got two or three films all to themselves and that lumbering bore Kharis got four. I guess there’s no justice for monsters.

Actually, Universal kicked off the idea in ’35 with Werewolf of London, a flawed-but-interesting effort laboring under the weight of Henry Hull’s stodgy scientist-turned-boogey-man.

Hull (to the left, on the left) was a dashing leading man on stage and played a fine string of crusty old-timers in the movies, but as a suffering monster he totally fails to grab our sympathy.

That’s rare in a monster movie, because normally the monster is the most interesting character. Here, Hull is such a constipated dullard, we want something unpleasant to befall him, and lycanthropy seems like just the thing.

Too bad, because this movie offers an interesting plot, some catchy dialogue, worthy special effects and camera work that lingers in the mind’s eye long after the silly story passes on.

Tue 7 Jun 2011

VICTOR MAXWELL (RE)REVEALED

by Terry Sanford

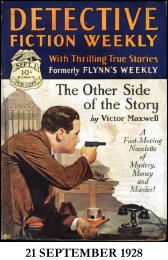

When I began collecting pulp magazines over thirty years ago, I quickly zeroed in on Detective Fiction Weekly in all its various incarnations. I bought a lot of nice copies for fifteen dollars or less and I found a good number of stories that I enjoyed.

I soon realized that I was a fan of Victor Maxwell’s Sgt. Riordan and Det. Halloran stories, a police procedural series that began in 1925. I found these stories were amazingly modern. There were no rubber hoses, beatings or hours spent in a darkened room with a bright light in the suspect’s face.

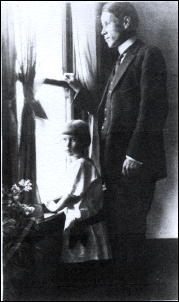

Instead there were, just as there are today, instances where the interrogator lied to the suspect trying to extract a confession. The police were very concerned about their cases holding up in court and whether a smart defense attorney would shred them. (Riordan and Halloran are the two gents pictured here to the right and below, stalwart fellows both.)

As I began to collect all the stories, I began to see that there was little information about the author. The stories appeared almost exclusively in Detective Fiction Weekly, hereinafter DFW, and that magazine did often run an “About the author” feature, but Victor Maxwell was never included. Sometime, somewhere I read that the Maxwell name was thought to be a pseudonym.

About four years ago, I wrote an article for the Mystery*File website titled “Those Detective Fiction Weekly Mugs.” It was so titled because we added artist’s renderings of the various characters featured.

I wrote this to share my enthusiasm for the hobby and one of my favorite pulps. There was no thought of a reward. A year later, Steve Lewis, our editor and chief was contacted by Don Wilde, who is the step-grandson of the man who wrote as Victor Maxwell. Mr Wilde had googled the pen name and discovered the article.

Although he never met his grandfather he had some items that might be of interest. Steve kindly put the two of us together and we had a fine time sharing information. Within a few weeks, he sent me pictures, correspondence, three unpublished stories and two unpublished novel manuscripts and more. A treasure trove for a Victor Maxwell fan!

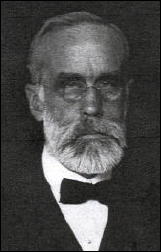

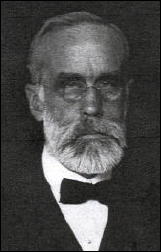

The identity of the author was never a secret. It was mentioned in almost all of his obituaries. It was simply lost over time. Victor Maxwell was a newspaper reporter named Maxwell Vietor.

Mr. Vietor was born on July 7, 1880 in New York City to Edward W. and Agnes C. (McCahey) Vietor. Edward Vietor was a medical doctor and within a few years, so was his wife. Edward was the founder of the Brooklyn Bird(watcher’s) Club, which exists today.

In January of 1882, Dr. Edward Vietor was summoned to a local residence where 10 year-old Bessie Thayer had become gravely ill after eating some candy she bought at the neighborhood candy store. Although Dr. Vietor was the third physician to see the girl that day, his was the correct diagnosis: arsenic poisoning! The girl died in his presence.

Dr. Vietor subsequently testified at a Coroner’s Inquest where it was resolved to turn the matter over to the police. There is no conclusion of the case that I’ve been able to find. Is it likely that this became a story that was mentioned from time to time in the Vietor household and fueled the imagination of young Maxwell? Perhaps.

At some point prior to 1910, the Vietors divorced. Dr. Agnes Vietor and Maxwell moved to the Boston area.

Maxwell graduated form Phillips Exeter Academy in 1898. He then attended MIT where the records show, “Maxwell Vietor ex.’02 has been granted a leave of absence for one year by the faculty, in order to take up practical railroad work with the Boston and Maine R.R.” Like many a college kid before him, Max soon realized that manual labor was not an ethnic gentleman.

According to several of his obituaries, he then returned to New York and began his newspaper career, first with the Sun and then with New York City News, a news distribution service.

Just prior to 1910, Max married Helena Haworth. The couple soon moved to Boston where Max continued as a reporter for The Boston Globe. By 1911, Max and Helena moved to the Vancouver, Washington and Portland, Oregon area.

That year Max made a haphazard attempt to keep a diary. Some of the entries deal with personal matters, but many of the pages just bore the letters, “P.P.” Finally months into the diary, those initials are spelled out: “Purple Pulp.” This was a humorous reference to his newspaper writing as he hadn’t yet begun to write for the real pulps.

Their only child, Alice was born on August 15, 1911. In 1915, tragedy struck the Vietor family. Helena’s car was discovered parked by a bridge spanning the Columbia river, but Helena was gone. The river flows into the Pacific ocean from that spot, which was used by many suicidal people over the years.

There was no trace of her after that day. Max would never remarry.

The January 20, 1916 issue of The Popular Magazine published the first Victor Maxwell short story, “The Little Girl Who Got Lost.” A second story appeared in August in that same pulp.

The family knew that Max occasionally wrote for the pulps full-time and one of those times may have been in 1917 when eight stories appeared in The Popular in an eight-month period.

Another minor mystery in Max’s life is evidenced by a letter found in his correspondence. The letter was from Ben W. Olcutt, Oregon’s governor and was dated April 5, 1920. The one-paragraph body reads:

“I am in receipt of your report of April 3rd, which I have read with much interest. In this connection and in passing I wish to say a good word for the work you have accomplished for the state in the capacity of special agent and for your highly intelligent and understandable report made in that connection.” There is no further explanation of his duties or service to Oregon.

Reporting must have lured him back as the pulp stories ended until his first appearance in DFW in 1925. That story would be the first of exactly one hundred appearances in the detective pulps, thanks, in part, to a novelette that was serialized over three successive issues of DFW.

Max had found a home there. All but seven of his detective stories were published by DFW. What prompted the inquiry is lost to the ages, but in March of 1931, Max apparently wrote the editor of DFW asking if he thought the readers might be tiring of Riordan.

At this point Max had sold them over fifty stories in a five-and-a-half years. Editor Howard V. Bloomfield wrote Max saying that he did not think anyone was tired of Riordan and strongly encouraging to either continue with the series or send in even more!

In addition to the detective stories, Max wrote three non-fiction articles for DFW. There were a smattering of other stories published in The Popular, Railroad (&) Railroad Man’s Magazine, Short Stories and Street & Smith’s Complete Magazine.

And that and reporting was his life, along with raising his daughter. About 1938, Max moved back to the Boston area where his mother resided. He would finish his newspaper career at the Worcester Telegram–The Evening Gazette.

His hearing was going and he would be completely deaf before his death. He switched from reporting to editing copy and would communicate with his fellow employees via handwritten notes. His last pulp story was in the January, 1944 issue of New Detective Magazine.

In 1950, increasingly worse back pain was plaguing Max. He went to the Mayo Clinic finally for help. Their diagnosis was inoperable cancer. From the clinic, he returned to the Pacific coast to be with his daughter. Just two weeks prior to his death, there was a heart-breaking exchange of letters between Max and his employer where he was told he was not eligible for a pension from them.

He died at a Portland hospital of a heart attack on October 4, 1950, survived by his mother and daughter.

The stories and the novels I have in manuscript form are not publishable as they are. But it is one hell of a collection and I want to thank Don Wilde for his generosity of time and spirit. And thanks to Steve Lewis for starting the ball rolling.

Note: The uppermost photo of Maxwell Vietor with his daughter Alice may have been taken in 1918. The date of the lower photograph is unknown.

Mon 6 Jun 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

GOING TO HELL IN A SAMPLES CASE:

JIM THOMPSON’S A HELL OF A WOMAN,

by Curt J. Evans

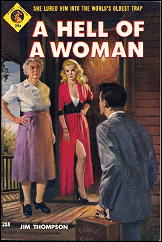

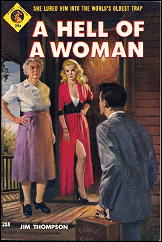

JIM THOMPSON – A Hell of a Woman. Lion #218, paperback original. Reprint editions include: Lion Library #138, pb, 1956; Black Lizard/Creative Arts #77, softcover, 1984; Vintage Books, softcover, 1990.

In a comment following Dan Stumpf’s recent review of Jim Thompson’s Savage Night, I mentioned my dislike of Thompson’s influential novel (widely acknowledged as a genre masterpiece), The Killer Inside Me. I do not deny the artistry of this narrative of a deeply disturbed mind, but the brutality and viciousness of it all was quite off-putting to tenderhearted me.

But I have persevered and finally read a second Thompson, another of his most-highly-regarded tales, A Hell of a Woman. And I am pleased to report that not only do I respect the artistry, I actually enjoyed the read this time — though the events described are nearly as lurid and depraved as those in The Killer Inside Me.

Hell chronicles the fateful collision of salesman Frank “Dolly” Dillon with the household of a really quite nasty old lady and her niece, the sexy (and really quite stacked) Mona Farrell. The tight-fisted and not overly scrupulous aunt whores her daughter out to various men, you see, so that she need not pay cash to these men for services rendered.

So if auntie wants some yard work done or hankers after a sparkly new set of flatware, say, the man who has such to offer is invited to visit Mona’s bedroom. If Mona doesn’t thereupon put out, Mona gets knocked about (auntie wields a mean cane at the age of about seventy).

Dolly is married to Joyce, a woman he has tired of, and he is attracted to Mona, who he sees as essentially virginal and innocent and sweet, even though auntie has handed her over by now to the army, navy, air force and marines, figuratively speaking.

Let’s let Dolly tell it in his own inimitable words:

“I thought what a sweet kid that Mona was, and why I couldn’t have married her instead of a goddamn bag like Joyce.”

Invited by such thoughts, murder comes to visit and makes itself at home….

The plot, which also involves Dolly’s diddling of the accounts of the business for which he works, the Pay-E-Zee Stores (in its own way as nightmarish a concern as Old Lady Farrell’s house), is pleasingly intricate and actually took some twists and turns that surprised me.

I came to realize A Hell of a Woman is less a crime story per se than a tale about the onset of criminal madness (which I think can be said about much of Thompson’s work). The progressive deterioration of Dolly’s mind, culminating in the famous split narrative conclusion, is fascinating, in its repugnant way (like the current Casey Anthony trial).

I found Dolly less monstrous than the charming gentleman whose deeds are remorselessly chronicled by Thompson in The Killer Inside Me; yet Dolly, by golly, is no day at the beach or picnic on a Sunday afternoon. If you won a “Spend a Day with Dolly” contest, you’d be thinking twice about accepting the “prize,” if you get me.

Here, for example, is Dolly as a restaurant critic:

“I sat down in a booth, and the waitress shoved a menu in front of me. There wasn’t anything on it that sounded good, and anyway, one look at her and my stomach turned flipflops… Every goddamned restaurant I go to, it’s always the same way… They’ll have some old bag on the payroll — I figure they keep her locked up in the mop closet until they see me coming. And they’ll doll her up in the dirtiest goddamned apron they can find and smear that crappy red polish all over her fingernails, and everything about her is smeary and sloppy and smelly. And she’s the dame that always waits on me.”

Dolly, one may come to realize, has women issues. In fact, though I never felt that the novel’s young women, Mona and Joyce, were as sufficiently-characterized as the men (some of the motivations seemed dubious or nebulous), this novel turns the whole noir femme fatale tradition on its pretty head, or so it seemed to me — though you would never guess this from the Vintage Crime/Black Lizard cover of the 1990 paperback edition.

And the ending is something that has to be read to be believed. Freud would have loved to have been able to analyze it, I’m sure.

The Black Lizard paperback edition also tells us that Hell is Thompson’s “homegrown version of Crime and Punishment.” I know Thompson has been called the “Dimestore Dostoevsky,” but it seems to me that he and the Russian are quite different personalities. Certainly it is difficult for me to glimpse redemption in the final hellish scene of Hell. Rather, it seems the grisly climax of the darkest nightmare.

In short: Awfully impressive, but also impressively awful.

Sun 5 Jun 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 3.1: Adventurers (Sleuths Without Portfolio)

It has always been accepted generally in television series’ creation that the central character or characters must have a franchise in which to meddle. That is, a seemingly legitimate reason to involve themselves in the lives and affairs of others.

The policeman, the journalist, the private eye, and a whole slew of other publicly accessible/available types are among the ones who have a licence to meddle in the lives of people whose paths they would not otherwise cross.

The adventurer in television Crime & Mystery is quite simply a sleuth without portfolio. These adventurers have the least reason to become involved in the affairs of others (given that, for the most part, their main activities are usually as thief, trickster, rogue-of-sorts, when they are not engaged as journalists seeking a hot story, former military types in search of peacetime thrills, or the extra-wealthy in search of “experiences”).

The adventurer-sleuth has its origins, primarily, in the novels and stories of authors such as E.W. Hornung and Maurice Leblanc, contributors to the Rogue School of crime and mystery literature.

Hornung’s gentleman-thief A.J. Raffles (whose adventures were first published in 1895) was the epitome of the charming rascal. Rather surprisingly, he did not receive a small-screen treatment until British writer-producer Philip Mackie and Yorkshire Television produced a single play, Raffles – The Amateur Cracksman, in 1975.

From this play, Mackie and Yorkshire developed the enjoyable 13-episode series Raffles (ITV, 1977) featuring a feline Anthony Valentine. There was also the 2001 BBC single drama, Gentleman Thief, starring the upper-crust Nigel Havers.

French author Leblanc created the Continental equivalent of Raffles with Arsène Lupin, another gentleman burglar. French television, of course, produced the first Lupin series for TV in the 1970s with Arsène Lupin (ORTF2, 1971; 1973-74), followed by Arsène Lupin joue et perd (A2, 1980), Le Retour d’Arsène Lupin (France 3, 1989-90) and Les Nouveaux Exploits d’Arsène Lupin (France 3, 1995-96). A fine (131-minute) feature film, Arsène Lupin, was released in France in 2004 starring Romain Duris and Kristin Scott Thomas.

What may be considered a part of this Early Adventurer-Sleuth Strain was DuMont network’s short-lived The Gallery of Mme. Liu-Tsong (1951), featuring the TV debut of Anna May Wong as the owner of a chain of prestigious art galleries, through the connection to which she conducted her mystery solving.

Both Boston Blackie (synd., 1951-53) and Mr. and Mrs. North (CBS, 1952-53; NBC, 1954) made their appearance around the same period but their rather homegrown adventures were pretty soon overshadowed by the witch-hunt obsessions of the Red Scare, the alleged Communist Menace sweeping America at that time.

It was inevitable then that Jerry and Pam North ran into a Communist cell in “Jade Dragon” (1953) and Boston Blackie tangled with foreign agents in “Black Widow” (1952) and “Crown Jewels” (1953). (And more about Blackie below.)

The Foreign Intrigue Cycle. Sheldon Reynolds’ Foreign Intrigue (synd., 1951-55), a European-based foreign correspondent adventure that sought out espionage rings in virtually every European city, and which at times evoked the noir qualities of Tourneur’s Berlin Express (RKO, 1948), was persuasive in turning similar adventure-sleuth series into rabid Commie-hunting rallies.

The opportunistic adventurer activities of Dan Duryea’s China Smith (synd., 1952; later as The New Adventures of China Smith, 1954) soon turned from solving insurance scams, murders and kidnappings to skirmishes with Red Chinese agents.

When, in the mid 1950s, the Falcon resurfaced in the shape of Charles McGraw as a syndicated TV series, Adventures of the Falcon (1954-55), the character had lost all trace of the sophisticated gentleman adventurer (of the George Sanders/Tom Conway RKO period) to become a hard-nosed U.S. Intelligence officer working on foreign assignments.

In a somewhat similar vein, the Eastern bloc adventures of anti-Communist journalist Brian Keith in Crusader (CBS, 1955-56) pulled no punches in his free-wheeling life as a writer and adventurer.

[Author’s note on the latter four paragraphs: please refer also to the earlier Part 3: Cold War Adventurers]

In what may be considered Relatives of Raffles, two particular series in the mid 1950s managed to capture the spirit of the television adventurer-sleuth:

Though removed from author Jack Boyle’s 1919 American-hardened version of Raffles, Boston Blackie (synd., 1951-53) was closer to its film interpretations (via Columbia, 1941 to 1949) with Chester Morris as the freelance crime solver than the original story (which, like Michael Arlen’s The Falcon, had only one published story as its basis). Rights holder-producer Frederic W. Ziv had tried a television version of the character as early as 1948 but it was the series starring Kent Taylor that became typical of the TV adventurers of the period.

Louis Joseph Vance’s Michael Lanyard (played by Louis Hayward on TV) as The Lone Wolf (synd., 1954-55) was another criminal-turned-adventurous rogue (previously via Columbia Pictures, 1935 to 1949) whose past as an urban outlaw (jewel thief) was put to good use as a globe-trotting crime fighter.

Perhaps one of the more interesting adventure seekers around this time was Dan Holiday, a former newspaper writer who advertised “adventure wanted” in a search for new story ideas. The character and format was developed originally for radio and starred Alan Ladd, who was heard as Holiday in the syndicated radio series Box 13 (produced by Ladd’s Mayfair Productions, 1948 to 1949).

Later, his Jaguar Productions attempted a television pilot; also starring Ladd, the half-hour “Committed” (1954) was shown as a part of General Electric Theatre (CBS, 1953-62). Why CBS Television didn’t pick up a Box 13 series with Ladd remains a mystery in itself.

The Bulldog Drummond Breed. And perhaps a final say in this overextended “footnote.” Military men in search of peacetime excitement was the basis for popular works by authors such as Sapper (H.C. McNeile), with his Hugh “Bulldog” Drummond, and for John Buchan, with Richard Hannay. Geoffrey Household’s upper class outdoor adventurers would follow later.

Sadly, television also failed to pick on a Bulldog Drummond series in the mid-1950s when Fairbanks Jr., as executive producer of the anthology Douglas Fairbanks Jr. Presents (ITV, 1956-57), produced the energetic “The Ludlow Affair” (1956; aka “Bulldog Drummond and The Ludlow Affair”). The production starred Robert Beatty as the thrill-seeking Drummond (who, in Sapper’s original work, also advertised for a “diversion” to his uneventful post-war life).

From a purely literary perspective, perhaps the lineage of the adventurer may be traced back to Rudolf Rassendyll (of The Prisoner of Zenda fame) and Sir Percy Blakeney (of The Scarlet Pimpernel)…?

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle).

Sun 5 Jun 2011

PRIME TIME SUSPECTS

by TISE VAHIMAGI

Part 3.0: Cold War Adventurers (The First Spy Cycle)

Projected rather than inspired by the post-war climate of the uneasy peace between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, the Cold War events from 1947 to 1950 (with the coming to power of Communist leader Mao Zedong in China, the arrest of Russian spies Klaus Fuchs, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, the Alger Hiss case, the start of the conflict in Korea, and the rise of Red-baiter Senator Joseph McCarthy) were instrumental in starting the first television Spy cycle.

A wholly American television genre, UK television (only BBC at the time) stayed well away from any “Red Menace” overtures.

Unlike the full headlong rush into espionage adventure during the following decade, the steady stream of spy stories during the first half of the 1950s were thinly-veiled attacks on the perceived encroachment of Communist influence into various parts of the world. The protagonists of these series were as varied as their assignments, which included government agents, military agents, roving journalists, and simply hot-blooded adventurers.

These series were often filmed as co-production ventures in Europe and Scandinavia. Among them, they featured the American correspondent hero of Foreign Intrigue (synd., 1951-55) and freelance writer of Crusader (CBS, 1955-56).

The government agents of Dangerous Assignment (synd., 1952), Doorway to Danger (NBC/ABC, 1951-53), Secret File U.S.A. (synd., 1954) and The Man Called X (synd., 1956).

The diplomat courier of Passport to Danger (synd., 1954-56) and the omnipotent, globe-trotting adventurers of The Hunter (CBS/NBC, 1952-54), China Smith (synd., 1952-54) and Biff Baker U.S.A. (CBS, 1952-53).

All engaged in dirty tricks against an even dirtier and trickier enemy.

It was all too clear that the villains represented agents of Iron Curtain countries in the west or elements of the Red Chinese threat in the east, but it was never stated or the countries named outright.

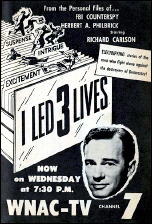

Of distinction, but no less shamelessly propagandistic in its relentless Communist infiltration hunting, was the double-agent series I Led Three Lives (synd., 1953-56). It was set in Boston for the most part but some stories took our hero Herbert Philbrick (a suitably nervous, twitchy Richard Carlson) overseas.

Apparently, the series was based on the real-life experiences of advertising executive Philbrick who, during the 1940s, acted as a volunteer undercover agent for the FBI. The modestly popular series displayed all the customary excitement associated with this type of concealed-identity drama (imminent danger of discovery, walking the shadowy path between the authorities and the enemy) while maintaining the hard and belligerent attitude found in other, more direct anti-Communist TV series.

During this period of hysterical Commie-bashing, more mainstream Secret Service exploits began to surface. Utilizing case histories (“from the files of…”) alongside original screen stories (ranging in historical scope from the First World War to contemporary times), the anthologies Pentagon U.S.A. (CBS, 1953), Top Secret (synd., 1954-55), I Spy (hosted by Raymond Massey; synd., 1955-56) and Behind Closed Doors (NBC, 1958-59) — even the frontier assignments of two Secret Service agents in the post-Civil War west, Cowboy G-Men (synd., 1952-53) — drew on stories involving political corruption, attempted kidnapping or assassination of government figures, private armies, and the general thwarting of the “enemy’s” skilled craft of deception and duplicity.

Arriving on the home screen just a year after April 1953 publication, it was inevitable that Ian Fleming’s first James Bond novel, Casino Royale, would show up during this period (as a 1954 CBS presentation of the anthology series Climax!).

However, only the bare bones of the novel’s plot were used (the high-stakes baccarat game and, unexpectedly, the infamous torture scene; although the latter was changed to an equally grisly pliers-and-toes ordeal), with the hero now a U.S. Intelligence agent (Barry Nelson as agent Jimmy Bond) and the villain (Peter Lorre’s Le Chiffre) the head of a Soviet spy ring.

The “based on the files…” fad soon became a TV genre fashion after the popularity of Jack Webb’s 1952-59 Dragnet soared. These pseudo-documentary series (such as The Line-Up, State Trooper, Highway Patrol and others) will be among my next observations.

But before that, there will be something of a footnote to this Part 3, looking at the 1950s TV adventurer sub-genre.

Note: The introduction to this series of columns by Tise Vahimagi on TV mysteries and crime shows may be found here, followed by:

Part 1: Basic Characteristics (A Swift Overview)

Part 2.0: Evolution of the TV Genre (UK)

Part 2.1: Evolution of the TV Genre (US)

« Previous Page — Next Page »