October 2011

Monthly Archive

Wed 12 Oct 2011

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

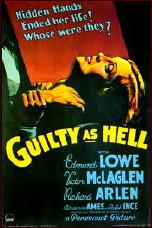

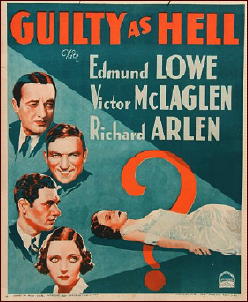

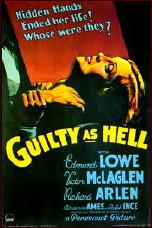

GUILTY AS HELL. Paramount, 1932. Edmund Lowe, Victor McLaglen, Richard Arlen, Adrienne Ames, Henry Stephenson, Elizabeth Patterson. Screenplay by Arthur Kober and Frank Partos, based on the play Riddle Me This by Daniel N. Rubin; photography by Karl Struss. Director: Erie C. Kenton. Shown at Cinevent 40, Columbus OH, May 2008.

Perennial battling comrades in What Price Glory and its several sequels, Lowe and McLaglen are once again costarred, with Lowe as as a McLaglen-baiting, brash reporter, undercutting police Lt. McLaglen’s murder investigation in an attempt to prove that Richard Arlen did not kill his mistress, wife of a prominent physician played by the cultivated, unflappable Henry Stephenson.

Richard Arlen is the convicted murderer and Adrienne Ames his sister who believes in his innocence. We see the murder and the framing set-up at the beginning of the film, so there’s no mystery for the audience to solve. Just the pleasure of watching an intricate cat-and-mouse game, with the murderer one step ahead of his pursuers until the final, tense confrontation.

A fine little crime drama, with the two stars lighting up the screen, with strong contributions by the supporting players, with the possible exception of Richard Arlen, whose lethargic performance Jim Goodrich attributed to miscasting.

Tue 11 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

General[11] Comments

This blog passed a plateau yesterday that had never been reached before, not even close. Tuesday was the first day that over 1000 visitors checked in, 1005 in all. The previous high was somewhere just over 800, so you can see what an achievement this was.

A good chunk of the traffic came to read Michael Shonk’s recent article about the 1959-60 season of the Philip Marlowe TV show, but congratulations and thanks go to all of the contributors to this blog. It couldn’t have been done without you!

Tue 11 Oct 2011

The 1980 Mystery*File AUTHORS’ RATING POLL, A to B.

I am reprinting this from Fatal Kiss #13 (May 1980), the same issue in which I reported the results of the first annual Top Ten Tec Poll.

The poll consisted of my listing ten authors whose last names began with either the letter A or B, then requesting respondees to rate them on a scale from 1 to 10. If you were not familiar with an author, then one of three categories were to have applied:

A = I never intend to read this author

B = I’d like to read this author but I haven’t yet

C = I’ve never heard of this author [or no vote]

There were 42 responses, including my own, from mystery readers scattered all over the world. Here are the results:

Author // Numerical Responses // Average // A — B — C

Eric Ambler 35 6.83 2 — 3 — 2

Nicholas Blake 26 6.65 3 — 7 — 6

Margery Allingham 32 6.00 2 — 6 — 2

Lawrence Block 23 5.89 1 — 11 — 7

Earl Derr Biggers 30 5.67 6 — 3 — 3

Charlotte Armstrong 28 5.29 5 — 6 — 3

Edgar Box 22 5.28 4 — 11 — 5

George Bagby 24 4.44 6 — 9 — 3

Edward S. Aarons 23 4.23 11 — 5 — 3

Carter Brown 24 3.79 10 — 5 — 3

One small surprise was the healthy showing of Lawrence Block, obviously not familiar to many people in 1980, but those who’d read him liked what they’d seen. [In 1980, Block had written a sizable list of paperback originals, the first three Matt Scudder books, and the first two “Burglar†novels.]

As I said at the time, I expected Ambler and Blake to do well, and they did. Aarons and Carter Brown did not do well with female voters, while Allingham and Charlotte Armstrong did not do as well with most male readers. And yes, I knew that Edgar Box was really Gore Vidal.

Since response was so high, I thought at the time that it was worth doing again. I’ll list the authors I suggested for the next poll, all of whose last names began with “C.” I don’t know if I have the issue in which the results were tabulated, or even if they ever were. I’ll have to do some searching in the garage where most of my back issues are stored.

If you’d care to record your opinions on the following authors, either in the Comments or by emailing me directly, feel free to do so:

Victor Canning, John Dickson Carr, M. E. Chaber, Raymond Chandler, Leslie Charteris, G. K. Chesterton, Agatha Christie, Manning Coles, James Hadley Chase, Tucker Coe, George Harmon Coxe, Frances Crane, John Creasey, Edmund Crispin, Freeman Wills Croft, Ursula Curtiss.

Tue 11 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

WICKED GOOD

A Review by Curt J. Evans.

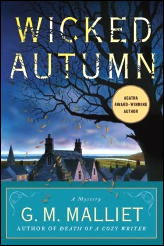

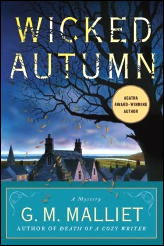

G. M. MALLIET – Wicked Autumn. St. Martin’s/Minotaur Books, hardcover, September 2011.

“Exton Forcett had remained immune from the corrupting influence of feminism. Even the Women’s Institute under the able guidance of Mrs. Laverock had confined itself to domestic matters and remained aloof from local politics. It knitted comforts, it baked meat pies for farmworkers, it made jams of curious and hitherto unknown consistency. None of its members had ever aspired to a seat on the parish council.”

— Miles Burton,

Murder M. D. (1943)

Who doesn’t love a good English village murder (or a “cozy” as these tales often are termed today)? G. M. Malliet, who in 2008 won the Agatha for best first novel for her Death of a Cozy Writer, has triumphantly updated this classic subgenre of English mystery with her fourth novel (the start of a new series), Wicked Autumn. Malliet’s satirical wit is magnificent and her cluing masterly.

Though in writing Wicked Autumn, Malliet no doubt was inspired by Agatha Christie’s grandmother of village mysteries, The Murder at the Vicarage (1930) — I was also much reminded of, from closer to the present day, Ngaio Marsh’s Grave Mistake (1978) and Robert Barnard’s A Little Local Murder (1976) and The Disposal of the Living (1985) — I have quoted above from a lesser known though first-rate English village mystery by Miles Burton (a pseudonym of Cecil John Charles Street), because I wanted to highlight one of the most delightful aspects of Malliet’s novel, her portrayal of the Women’s Institute of her village, Nether Monkslip (the book is dedicated to the National Federation of Women’s Institutes).

The machinations within this group — whose overbearing president, Wanda Batton-Smyth, is murdered in the course of the tale—make highly amusing reading. One of the great pleasures, surely, in the English village mystery is the frequently wicked satire (somewhat belying the reputation of these tales as “cozies” that one finds in it. The Miles Burton passage above, for example, is delivered very much with its author’s tongue in his cheek.

Christie’s brilliant satire in The Murder in the Vicarage — a novel one contemporary reviewer compared to Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford (1851) — is much underappreciated today, but clearly Malliet has learned much from the Great Lady. Malliet’s wickedly barbed writing is an abiding delight throughout Wicked Autumn:

“Wrapped in a fluffy white mohair dress of her own design…her hair clipped short around protuberant ears, she resembled a Chihuahua puppy abandoned in a snowdrift.”

“[The figurine] was made of plaster of Paris and amateurishly painted, the shepherdess’s hectic expression suggesting a facelift operation gone wrong, the receipt of a telegram containing bad news, or the irretrievable loss of her flock.”

“The rest of the room was of a Laura Ashleyish theme of prints and patterns of coordinating colors and contrasting patterns, a style so irredeemably British as to be impossible to eradicate from the Jungian collective design unconscious.”

“A typical man of his generation, Lily’s uncle had taken one look at her knobby-kneed, wiry-haired self, aged twelve, and privately predicted she would never marry unless a female-targeting plague killed off every other woman on the planet.”

The women of the village are similarly memorable, especially Wanda Batton-Smythe, a classic murderee. Wanda is so deliciously obnoxious and objectionable we ironically miss her when she’s gone. She’s a brilliant updating of the village battle-axe matron. Other classic types given updates and new life by Malliet are:

â— Awena Owen, the “New Age” mystic (yes, they had these in the Golden Age mystery too, under different names)

â— Suzanna Winship, the village vamp

â— Mrs. Hooser, the something less than smoothly competent housekeeper

â— Agnes Pitchford, the nosy and keen-minded octogenarian retired schoolmistress (I surely won’t be the only person reminded of Miss Marple and Miss Silver)

â— Major Batton-Smythe, Wanda’s husband (almost straight out of the pages of a Christie)

â— Frank Cuthbert, futile local author (self-published)

Though it is a cliché to say it, a book as delightfully written as Wicked Autumn would be an enjoyable read even without its murder and solution; yet I am pleased to report that Malliet handles this aspect of her tale quite deftly as well. The clues, which are of the textual sort favored by Christie, are close to the level of the great Golden Age Crime Queen herself.

There also ultimately is some poignancy in Malliet’s handling of the Batton-Smyth family (Malliet’s passage on the cruel difference for many couples between the glittering fantasy of retirement and its drab reality is acute) — proof, if it be needed, that the cozy can offer emotional depth as well as surface charm.

Indeed, the solution to the murder in Wicked Autumn is rather un-cozy when one thinks about it. Wicked Autumn definitely illustrates W. H. Auden’s view that the murderer in the English village mystery must be cast out in order to restore the village to its state of grace. In this respect, the novel is more aesthetically pure than some of its Golden Age forebears, where murder occasionally is allowed to pass unpunished.

The detective in the tale is an amateur rather improbably brought in, in classic fashion, to help the police with the investigation: Max Tudor, the local Anglican minister. Max, it seems, used to be MI5. His back story is threaded through the tale. Undoubtedly many readers will find this material of greater interest than I did. (I am of the old school and do not expect my detectives to have interesting back stories.)

I did enjoy Malliet’s thoughts on the present-day status of the Anglican church, however: “Especially in an age when it was felt the church was circling the drains, some people clung to whatever looked certain and solid, making them less able to handle ambiguity and apparent contradiction.”

Naturally, Max is handsome, charming, straight and a bachelor; and Malliet cannily opens several romantic possibilities for him in his first novel. No doubt many Malliet fans (of whom there should be increasing numbers after this novel) will enjoy following how Max’s love life develops. For my part, as long as Malliet keeps writing mysteries this amusing, insightful and clever, I will abide even fairly heavy doses of love interest!

Final Note: I should add that in Wicked Autumn Minotaur Books has produced an extraordinarily attractive book. There is a stunning endpaper map, an apt falling leaf motif running though the pages, and attractive and clear type. In an age where publishing quality often seems increasingly slipshod, Minotaur Books is to be praised along with the author.

Mon 10 Oct 2011

REVIEW AND HISTORY:

The 1959-60 PHILIP MARLOWE TV Series

by Michael Shonk

PHILIP MARLOWE. ABC-TV. 1959-1960. Tuesday 9:30-10pm(E). Goodson-Todman Production with California National Productions. Created by Raymond Chandler.

“Murder Is a Grave Affair.” March 8, 1960. Written and produced by Gene Wang. Directed by Paul Stewart. Cast: Philip Carey as Philip Marlowe, William Schallert as Police Lieutenant Manny Harris, Gene Nelson as Larry, Jack Weston as Artie, Betsy Jones-Moreland as Marian, Maxine Cooper as Janet. Episode available on DVD: TV GUIDE Presents Master Crime Solvers.

A young woman in love with Larry, a married movie director, confronts his wife. The wife, Marian tells the girl she won’t stop Larry if he wants a divorce, and then celebrates with her lover. Larry is not happy. The girl means nothing to him, just one of a “hundred.” She threatens to go to the papers. Larry also has to deal with the reaction from his secretary and lover, Janet. But he’s a guy and these things happen.

The girl turns up dead due to an unvented gas heater. Her friend Artie, who loved her, finds the body. Both he and the girl’s father believe Larry killed her, and Dad hires Philip Marlowe. Marlowe uses the typical TV PI’s method for solving crimes. The suspects are cleared one by one until only one remains who, in a burst of illogic, no hard evidence, and the closing credits fast approaching, confesses.

Philip Carey could have made a great Marlowe, but the way the character dressed and lived, the fake scar on his cheek, his attitude towards the cops, all of it left Carey playing a character unlike the one Raymond Chandler created.

Among the few positives, Betsy Jones-Moreland as the wife played the part with an odd amused indifference that was a fresh choice for that type of role. The script featured a brilliant twist that would surprise viewers today.

On the negative side, the theme music is a forgettable jazz tune with a slight Bossa nova beat, as you can hear from this YouTube clip of the opening credits. There were no noirish elements, even the Day for Night scenes at the graveyard lacked any style or visual substance.

Take the Philip Marlowe name away and this was just a good TV mystery typical of the time.

Now, a look at the creation of the series. It began July 1957 when a deal was signed between Raymond Chandler and Goodson-Todman Productions to produce a TV series based on the character Philip Marlowe.

According to Billboard, July 22, 1957 issue, Chandler would be the series story editor. At this point the pilot was to be filmed in August 1957, Goodson-Todman producing with Screen Gems. Casting had not yet happened nor had the episode length been decided, though the hour-long format was favored. The plan was to sell it to a network for September 1957 (Billboard, July 29, 1957).

Broadcasting (February 10, 1958) reported the pilot done but not yet sold.

At one point, Screen Gems dropped out (if it had ever been involved). Broadcasting (December 15, 1958) reported a signed contract between Goodson-Todman and NBC to produce thirty nine episodes “for showing on NBC-TV starting either in April or the fall.”

This is probably when California National Productions got involved. According to Broadcasting (February 2, 1959), “CNP operates under two sales units. NBC Television Films, which syndicates largely first-run properties, and Victory Program Sales, which handles re-run series.”

March 26, 1959, Raymond Chandler dies. Was he still involved with the show? I doubt it.

For some reason the series appeared on ABC not NBC and lasted only (reportedly) twenty six episodes before it was dropped.

Broadcasting (September 28, 1959) had a review of the first episode. Scroll down and click on 9/28/59 issue and scroll to pages 48 and 50.

No title for the episode is given and it lists a different producer (William Froug). It gives the air date as September 29, 1959 instead of the currently believed October 6.

Based on the review, Marlowe is hired in that first episode by a reformed gangster to keep his daughter from running away with a young man. The young man and Marlowe fight. Marlowe wins. A gangster with a grudge against Marlowe’s client helps the kid to take on Marlowe again. Marlowe wins but during the fight the bad guy kidnaps the girl. Marlowe chases. Marlowe and bad guy fight. Marlowe wins and bad guy is killed.

Time magazine did a cover story “These Gunns For Hire” (October 26, 1959) about the TV detectives of the 1959-60 season. I highly recommend you read the entire article, which you can easily find online.

According to the article the 1959-60 season had sixty-two series (network and syndicated) featuring “some variation of Cops & Robbers.”

Also from the article, “Carey has long been an admirer of Chandler’s books, is openly proud of the fact that Chandler told him he would make a great Marlowe. What Chandler (who died in March) would think of the rest of the TV show is not quite so certain.”

Philip Marlowe is less for the Chandler fan and more for those who enjoy watching even the average TV PI of the late 1950s.

TIP OF THE HAT: To RJ of TV Obscurities for helping me find another online source, the Broadcasting magazine archives.

Mon 10 Oct 2011

PAUL KEMPRECOS – Neptune’s Eye. Bantam, paperback original, September 1991.

This is a long book, over 300 pages of small print, and so even at a $4.50 cover price, you’re getting your money’s worth. It’s also a private eye novel, and while I like PI novels almost more than any other kind of detective story, I think that 300 pages of small print is too long. While PI stories might not need to be short, they do need to be snappy, and after 300 pages I found that this one had long since lost its snap.

It is the second adventure for Aristotle “Soc” Socarides, the first being Cool Blue Tomb, published a few months before, also by Bantam. It begins as a missing daughter caper, but quickly heads off in several directions: first, as a murder mystery; then as an industrial espionage story involving a notorious arms dealer and a large Cape Cod scientific community; as a World War II Nazi novel; and as a deep-sea diving adventure.

While all this is going on, Socarides must also locate his sister, who has run away from home. In a certain sense, I disapprove of this trend. Hercule Poirot never had to work on a case for his mother. Sam Spade never had to work on a case for his mother. Perry Mason never had to work on a case for his mother. (The list goes on.)

Or in other words, everything is in here except for the stopper for the kitchen sink. Socarides is also a wise mouth when it comes to cops who have an attitude toward PI’s who have wise mouths and seem to barge in on murder cases where they’re not wanted. I’ve read this before, and so have you.

There are also times in the tale when Socarides’ actions are also very dumb, and that he is alive to tell the story when it’s over came as quite a surprise to me. The murder mystery has been solved at a point when there are still fifty pages to go, which are then used to clear up all the other loose ends. Neatly enough, I should add, but by that time I’m afraid I just didn’t care enough.

Rating: C.

— This review was intended to appear in

Mystery*File 35. It was first published in

Deadly Pleasures, Vol. 1, No. 3, Fall 1993 (somewhat revised).

The Aristotle “Soc” Socarides series —

1. Cool Blue Tomb (1991) [Shamus Award for Best First PI Novel]

2. Neptune’s Eye (1991)

3. Death in Deep Water (1992)

4. Feeding Frenzy (1993)

5. Bluefin Blues (1997)

Since 1999 Paul Kemprecos has been the co-author of several novels in Clive Cussler’s “NUMA Files” series. At least the first two books of his own series are hard to find, and in nice condition have become rather pricey (in the $20 to $30 range).

Sun 9 Oct 2011

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

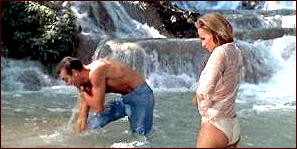

DR. NO. United Artists, 1962. Sean Connery, James Bond, Ursula Andress, Joseph Wiseman, Jack Lord, Bernard Lee, Anthony Dawson, Zena Marshall, John Kitzmuller, Eunice Gayson, Lois Maxwell. Director: Terence Young.

What can I say? This was one of those movies that hit me at an impressionable age and gave me the notion that it might be fun to Fight Crime for a living. Watching it now, in the Wisdom of my advancing years, I tried to figure out just how it got so dated; I mean, here’s the Hero, running around in a button-down suit, with a dumb hat like my Uncle Wayne used to wear, cracking corny jokes and slicking his hair down with Vitalis.

Then I realized just how long it has been since I was Young and Impressionable.

Let me try to put it in Historical Context: The Movies learned to talk somewhere around 1930. This film was made in 1962, some 32 years later. How much time has elapsed since the making of Dr. No and the writing of this piece?

I tell you, it’s enough to make a man think.

It may be, then, that in not so many more years, Dr. No will seem as charmingly energetic as The Westland Case and The Mystery of the Hooded Horsemen. It certainly has a lot going for it, what with fights, car crashes, bad back-projection and the improbably-cantilevered Ursula Andress in her screen debut.

Maybe so.

Sun 9 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

FRED DICKENSON – Kill ’Em with Kindness. Bell Publishing, hardcover, 1950. Hardcover reprint: Unicorn Mystery Book Club, July 1950. Bestseller B131, digest paperback, no date.

Although you couldn’t fault Ronald Tompkins’s physical preference in females, you could definitely criticize his judgment in regard to brides. Six was the number he had reached, with the marriages lasting from 16 hours to six weeks.

As he is preparing for No. 7, he is planning to hire Mack McGann, former FBI man and now private eye, because he fears for his life.’ While McGann is elsewhere in Tompkins’s house interviewing an inebriated disc jockey who had just brought Tompkins a personal warning, Tompkins is shot dead in his study.

Dickenson’s only mystery breaks no new ground, indeed doesn’t disturb any of the old ground. The murderer is patent, the characters not all that interesting, and McGann’s FBI training apparently wasn’t up to that outfit’s best. However, the dialogue and McGann’s sense of humor save it from being just a time waster.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 12, No. 4, Fall 1990.

Sun 9 Oct 2011

From the introduction:

“Davis Dresser (1904-1977) was an American writer best known for the Michael Shayne mystery series, written under the pseudonym of Brett Halliday. […]

“Besides writing the Michael Shayne series, Dresser was also prolific as a western writer [including many of the “Powder Valley†series as Peter Field] and had cut his teeth writing ‘love novels’ for the lending library publishers of the 1930s. […]

“[This] is an attempt to draw together, in one place, all of Davis Dresser’s books and pseudonyms, in as many editions as possible, and to explicate the attributions of the more obscure pseudonyms.”

Check it out here:

http://www.philsp.com/homeville/KRJ/Davis_Dresser_Bibliography.pdf

Sat 8 Oct 2011

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

REBECCA JENKINS – Death of a Radical. Quercus, UK, softcover, 2010.

Genre: Historical Mystery. Leading character: Frederick Raif Jarrett; 2nd in series. Setting: England, 1813.

First Sentence: Ancient walls rose up against an indigo sky.

It’s 1812 and the beginning of the industrial revolution but not everyone is embracing technology. Luddites and radicals fear these advances will be the end of independent craftspeople.

In the town of Woolbridge, the Easter fair threatens to erupt in violence. One of the local judges brings in the military as a precaution. Jarrett, agent to the Duke of Penrith, must look to his young, visiting cousin, balance the attentions of two lovely ladies, and find out who murdered a man found laid out neatly in his bed.

As soon as I began reading Death of a Radical, I was immediately reminded of the reasons why I enjoyed the first book, The Duke’s Agent (1997).

I value an author’s ability to create a sense of place through written pictures: “This was land pared down to its primitive bones. …an enchanted land that might flick them off into oblivion with a shiver of its crust.†Now there’s an image that can’t help but stay with you.

Jenkins brings the place, people, and story to dimensional life for the reader. This is enhanced by the excellent dialogue. The speech is reflective of the period but not labored. The exchanges between the cousins, Raif and Charles, have the natural banter of those who are close. The young cousin, Favian, whom the older cousins refer to as “Grub,†is convincing in idolization of his older cousins while stretching his newly-found independence.

There are quite a lot of characters in the story, some of whom were more fully developed than others and I occasionally had trouble remembering who was who. I often do wish more publishers would allow for a cast of characters.

What I did particularly appreciate was that through a tragic story and bits of conversation, we learn much more of Raif’s background and history. Raif and Charles are characters in whom I’ve become invested and about whom I definitely want to know more.

One element I found interesting was that, to me, the book has a feel of being very much a “man’s†book, similar to the Patrick O’Brian books. This is not, at all, a criticism. The principal characters are all very much male, even with the female characters adding a romantic/sexual element. The series has a definite swashbuckler feel to it, even though it’s on land. It may be due to the period in which it’s set or the strength of the male characters, but I very much liked it.

The story has a very good plot with good twists, diversions and side threads. There is an excellent buildup of tension and a terrible release from it. The end was at points

both poignant and highly satisfying with the door being left open for more to come.

I do sincerely hope so although I also hope it’s not another 13 years before we see Jarrett again. Please get writing, Ms. Jenkins, your readers are waiting.

Rating: Very Good.

« Previous Page — Next Page »