February 2014

Monthly Archive

Tue 11 Feb 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

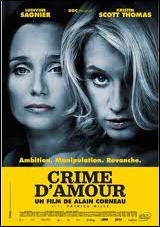

EUNICE MAYS BOYD – Murder Wears Mukluks. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1945. Dell #259, paperback, mapback edition, no date [1948].

Last summer, when I purged my collection preparing to remodel my room, I thought long and hard about one book, the Dell mapback edition of Murder Wears Mukluks, by Eunice Mays Boyd, author of Murder Breaks Trail, Doom in the Midnight Sun, etc. Should I pitch it or keep it?

It didn’t seem likely I’d ever read this thing, but in some way my library seemed richer, warmer, more diverse and enjoyable just because there was a book there somewhere called Murder Wears Mukluks. Does anyone know what I mean?

Anyway, I compromised by putting Mukluks on my to-be-read shelf and a few weeks ago I actually started on it, only to give up fifty-some pages inwards. There was plenty going on: jealousy, murder, bitter feuds and even a ghostly apparition, but the characters never seemed to be anything more than figures in a puzzle, their whole existence in these pages defined by their relationship to the murder.

As such, it got rather hard to take much interest in them, and I gave it up as a bad job with two hundred unread pages to go.

Which leaves me once again with the same problem I had last summer: keep it or pitch it? I’d sold off much much better books than this, but there’s just something about going through my shelves and discovering Murder Wears Mukluks that appeals mightily to my heart.

Any thoughts?

Editorial Comment: My own review of this book was posted on this blog a couple of years ago. Check it out here.

Mon 10 Feb 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

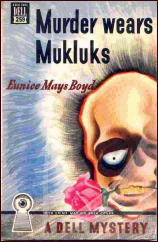

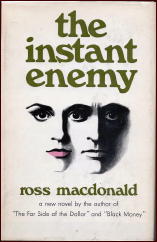

ROSS MACDONALD – The Instant Enemy. Alfred A. Knopf, hardcover, 1968. Reprinted many times.

In many ways The Instant Enemy is typical of Macdonald’s entire output, in that the emphasis is on story and plot, and the personality of the detective, one Lew Archer, hardly ever enters into it.

Archer, in other words, is an observer, and we never get much of an insight into what makes him tick. One exception I noted was on page 112 (in the Warner paperback edition I read), where the possibility of getting paid $100,000 jars Archer into the unexpected realization that maybe he might even retire.

That’s probably a million dollars in today’s money, and he feels pretty good about the idea. The moments lasts for only a page, though, and then it’s back to the case on hand. It starts out simply enough — he’s hired to bring back a runaway daughter who’s gone off with a psycho boy friend with a sawed-off shotgun.

Things are never that simple in a Ross Macdonald book, however, and soon all sorts of entanglements with the past begin to emerge, like pulling a root out of a sewer pipe and finding you’re dragging the whole tree out with it. If trees had Oedipus fixations, I think the analogy would be complete. (See page 146.)

Although Instant Enemy is much like all of Macdonald’s other books, and the ending is absolutely terrific, I don’t think this is one of his better ones. (Those of you you’ve read them all recently, please feel free to contradict me on this.) I think it may be the pacing. It’s relentless; it doesn’t give up for a minute; and if you’re so minded, it could become downright monotonous.

Archer is on the go from the beginning of the book to the end. When he’s tired for a moment, he pulls over to a motel and sleeps for a couple of hours, and then he’s on the road again. I think a good many readers are going to feel the need to pull over themselves, right about the three-quarters mark.

If I’m right about this, and maybe I’m not, second-rate Macdonald is still number-one goods, but in this particular case, the really prime stiff is all at the end. People who prefer the light frothy sort of mystery simply aren’t going to get there.

— Reprinted from Mystery*File 37, no date given, slightly revised.

Sat 8 Feb 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

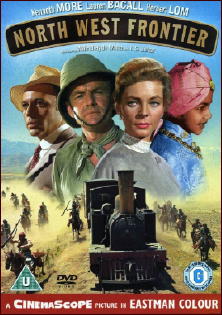

NORTH WEST FRONTIER. The Rank Organisation, UK, 1959. US title: Flame Over India. Kenneth More, Lauren Bacall, Herbert Lom, Wilfrid Hyde-White, I. S. Johar, Ian Hunter. Directed by J. Lee Thompson.

Set your movie on a train and you already have my attention. Make one of the classic action films of all time with a first rate cast and superb tension from an expert at directing action and suspense (Cape Fear, The Guns of Navarone) *, and you have a first rate film shot in gorgeous color and on location.

Kenneth More is a British officer in command of a small troop of Sikhs in an isolated kingdom on India’s rugged outlaw ridden northwest frontier. A rebellion has broken out against the local Maharajah, and the British consul (Ian Hunter) wants More to get a group of Europeans trapped in the palace out safely — and along with them, the Maharajah’s young son and his American tutor (Lauren Bacall).

Among the European’s are a Dutch journalist with Indian blood (Lom), a garrulous older man (Hyde-White), a gun runner, and a redoubtable older Englishwoman. Their only means of escape an aging train engine, her Indian driver (I. S. Johar), one coal car, a flat car, and a passenger car.

Film goers used to today’s frenetically paced films will find the fact this one bothers to stop to develop character, build an intriguing relationship between professional soldier More and doubting American Bacall, and establish the other characters as well, a bit slow, but even they will be impressed by the action sequences beginning with the breakout from the surrounded palace in the train and including running gun fights, a perilously damaged bridge across a precipitous gorge, and a final full out assault by hordes of tribesmen on horseback while a traitor in their midst pins the passengers and soldiers down with a .50 caliber machine gun he has taken over.

More and Bacall have real spark together, Lom provides both menace and depth, and Hyde White is his usual charming self, but the real surprise of the film is Johar, who takes what could be a stereotyped local and gives him both real courage, strength, determination, and character. Both he, and through him the aging train engine he loves, become compelling characters in the film.

He takes what could be an embarrassing and potentially racist stereotype and gives him dignity and humanity.

The film isn’t an old fashioned paean to the Raj though, in the Gunga Din or Lives of the Bengal Lancers tradition. It asks questions, and while it is unstinting in its admiration for More’s professional soldier, it, and Bacall’s character, bring up the question of what right he or the British Empire has there. And More is no superman, but a tough wry professional, limited perhaps in his devotion to his duty, but also human, canny, good humored, and courageous.

This is a stunningly photographed film with an intelligent script and a real sense of the time and the place.

One scene in particular in a crowded engine room while a rickety and dangerously open donkey engine runs the pumps to water the train’s engine while Lom is left alone with the prince is splendidly shot and guaranteed to get you on the edge of your seat.

Within the confines of an action packed thriller it takes on questions of race, fanaticism, duty, freedom, and individual courage without ever faltering in the line of suspense and action or brushing the questions it asks off with simple answers.

In relation to what has been happening in the Middle East in recent years it may be as pertinent as ever.

Granted, despite the best efforts of all concerned there isn’t a lot of doubt who the villain proves to be, but that said, he is given both dignity and depth. You may be pulling for him to fail and cheering for the heroes to escape, but you can’t ignore his points or his own plight. All the major characters are presented as real humans rising or failing to rise in a crisis, not as mere plot points.

And the film manages to end on a nice note of irony — a recognition that an era was coming to an end and a new world being born. It’s the perfect coda to a first class adventure film and a fine study of people caught in desperate circumstances and showing grace under pressure.

* Sadly Thompson did not live up to his early films and ended up hacking out some tired and unimpressive Charles Bronson films late in his career.

Sat 8 Feb 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

A. FIELDING – The Cautley Conundrum. Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, January 1934. Published in the US as The Cautley Mystery: Kinsey, hardcover, 1934.

A later appearance of Chief Inspector Pointer, and in comparison to the breakneck pace of the previous book [The Net Around Joan Ingilby], just reviewed, this one, some readers may feel, is downright soporific. Well, not I, even though most of the 250 plus pages take place within walking distance of Bunch Cottage, where Jack Cautley, one of the four Cautley cousins makes his home, even though it is Major Howard Cautley to whom it actually belongs.

And among the four, it is the Major who has the money, and it is he who on page 40 is found dead, lying across a stile after having gone shooting, his gun lying beside his body. It is at first assumed to have been a dreadful accident, but at the same time, a valuable necklace, a family heirloom, is discovered to have gone missing. The local police in the guise of Superintendent Wanklyn, at the Woodhaven police station, do not believe strongly in coincidence (nor does the faithful reader) and eventually Pointer is called in from Scotland Yard.

Accordingly, in mind-expanding fashion, there follows a story full of questions, evasive answers, long-shot inquiries, other deaths, puzzling tales, and a plethora of clever observations. The characters are extremely well-defined as well – there is no mistaking one for another, even though there many, many of them, and all of them have their own desires and motivations. It’s not a book for most modern readers, though. It’s too stationary. It moves, and yet on the surface, it doesn’t. There’s no flair there, you might say.

Or you might not. I enjoyed it, but largely as an intellectual endeavor only. I truthfully have to admit that I enjoyed the earlier adventure more, as rough and unruly as it was. If I’d read this one first, I confess, I probably wouldn’t have read the one I did read first.

Thu 6 Feb 2014

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

MICHAEL O’HALLORAN. Republic Pictures, 1937. Wynne Gibson, Warren Hull, Jackie Moran, Charlene Wyatt, Sidney Blackmer, Hope Manning, G. P. Huntley Jr. Based on a novel by Gene Stratton Porter. Director: Karl Brown. Shown at Cinefest 26, Syracuse NY, March 2006.

One of the great film reference books is Jack Mathis’s Valley of the Cliffhangers, a fascinating detailed history of the Republic serials, and during his research for additional volumes on the studio,he was allowed to have prints made from studio negatives of some rare titles. Three of these ware shown during the weekend.

Unfortunately, this film, in which Wynne Gibson, an irresponsible party girl, attempts to present herself as a fit parent in a custody struggle with Sidney Blackmer, her dull respectable husband, continues the Cinefest tradition of scheduling a dog to initiate the screenings.

The plot is mainly an excuse to showcase what my fellow attendee Jim Goodrich referred to as the “unquestionable” talents of a popular young child actor, Jackie Moran, whose invalid sister becomes the do-good project that Gibson takes on to improve her image.

About twenty minutes of the film don’t survive (except for the soundtrack) and that was something of a blessing. It didn’t, however, deprive us of an especially saccharine (and inept) imitation of Shirley Temple by a child actress who does a walk-on.

Wed 5 Feb 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

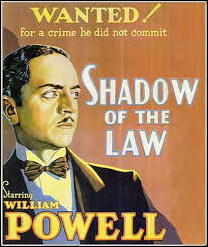

SHADOW OF THE LAW. Paramount Pictures, 1930. William Powell, Marion Shilling, Natalie Moorhead, Regis Toomey, Paul Hurst, George Irving, Frederick Burt. Screenwriter John Farrow, based on the novel The Quarry by John A. Moroso (Little, Brown, 1913). Director: Louis Gasnier.

Back in 1922 a man named Robert Elliott Burns was sentenced to hard labor on a Georgia chain gang for his part in an armed robbery that netted him and two other men less than six dollars. Probably only Steve and Walter are old enough to remember, but Burns escaped from the chain gang and made a new life for himself under another name, eventually becoming a prominent businessman in Chicago and something of a celebrity when his wife (who had been blackmailing him) betrayed him to the law after getting a cash settlement from him in exchange for a divorce.

Burns could have fought extradition but agreed to return to Georgia when corrections officials there promised him quick release after some nominal service. Instead, they reneged on their promise and he was returned to the chain gang for “extra attention†from the guards, with no release in sight. Eventually Burns escaped again and wrote I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang (Vanguard, 1932), which finally secured his freedom.

Burns is best remembered for the movie made from his book, but his personal story seems to have been much on the mind of John Farrow, screenwriter of the film Shadow of the Law, which appeared a full two years before I Am a Fugitive hit the bookstands and movie screens.

The story in Shadow of the Law is slightly changed, but the essential elements are there: William Powell stars as a decent if amorous gentleman who gets in a scrape over a lady (perennial vamp Natalie Moorhead) and ends up accidentally killing a man—whereupon Ms. Moorhead, fearing scandal or worse, promptly decamps, leaving Powell with no witness to clear him of a murder charge that sends him to prison.

A few years later, Powell is a hardened-enough convict to pal up with a thief (well played by Paul Hurst) and exploit the warden’s trust in him to break out of jail. When we next see him, he has become a highly-placed executive, respected by the workers in his factory and engaged to the owner’s daughter — but determined to find Moorhead and clear his name.

He does eventually find her, or rather Hurst does, but she proves smarter than Hurst thought and more avaricious than Powell suspected, leading to some plot twists both melodramatic and highly entertaining.

In fact, the writing and direction (by Louis Gasnier) in Shadow keeps the story right on its edge, offering some juicy plot twists and a couple of suspenseful moments, one of which – as I realized what Powell was going to do to himself and watched him calmly set about it — I swear made my skin crawl. Director Gasnier is not well known as an auteur (unless you count Reefer Madness) but his work here shows a stylishness and pace perfectly suited to the subject.

Mon 3 Feb 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[5] Comments

A. FIELDING – The Net Around Joan Ingilby. Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1928. Alfred A. Knopf, US, hardcover, 1928.

According to a huge amount of research done by John Herrington, [FOOTNOTE] A. Fielding was in reality Dorothy Feilding, who between 1924 and 1938 was the author of 24 detective novels, an absolute terrific pace, with one last book appearing in 1944.

Her primary character is Chief Inspector Pointer, who did not appear in all of them, and who, on the basis of the two books read so far, does not always appear in the ones he does until a certain distance into the story. He’s from Scotland Yard, and the local police do not always see fit to call in them in right away. (I am hedging here, trying not to tell you more than you should know, and as soon as I tell you that, I know that that’s telling you too much in and of itself.)

But all digressions aside, let me tell you about this one, which is a doozie and a half, as my mother (or was it my grandmother) used to say. In Chapter One, there’s no detective story or mystery thriller in sight. On board ship, where such chance meetings often take place, just before landing, journalist Martin Blair meets the fairy princess of his dreams, briefly but most magically, yet with no likelihood of ever seeing her again.

Chapter Two. After fashioning a successful career for himself, Blair comes across a strange but apparently accidental death, that of a woman who took refuge in a shed near a outdoor charcoal burning facility and was later found asphyxiated by the fumes. Investigating further on his own, Blair comes to the conclusion that foul play was involved, and he writes the story up for his newspaper, complete with an all-but-accusation of the guilty party, Miss Joan Ingilby, the missing governess of the dead woman’s child.

Well, I suppose you know what comes next. Joan Ingilby and his fairy princess are one and the same, and while Blair desperately tries to take back his accusation, his recital of the facts is all too convincing, and Joan must go into hiding while Blair tries to make amends and catch the real killer.

There may be a “first†involved here. Can you think of any other story in which an accused murderer comes back into the story disguised as her older sister in order to help in the investigation?

Here’s a description of Joan’s first encounter with Chief Inspector Pointer, taken from page 137:

Her eyes softly shining, she shook hands with the newcomer; he looked much younger than she had expected, and more distinguished too. As his fingers closed around hers, there flowed through her a sense of his power. A man dangerous to a criminal, was her first thought; a difficult man to deceive. She had a definite impression of a fine, clear, cold intellect, a great personal dignity, and of unusual force of character – force that showed in his quiet manner, in the clean, firm lines of the lean face and figure. In a certain stillness about him that meant vast reserves of strength, physical and mental.

She tingled with excitement. Would he suspect her? Would he help her? This brown-faced man with the pleasant but very enigmatic grey eyes.

Pointer will need all the strength that is suggested in this passage. The trail leads to France, and to Marseilles in particular, to a den of iniquity there never seen in the likes of Innes, Christie or Carr. Kidnappings, last minute escapes, recaptures, underground passages and more – unlike anything I have read in more normal fiction in many a day. (Maybe I’ve been reading the wrong stuff. This was great.)

Not so great, though, were the many lapses in story-telling continuity. In the early going, characters appear only as they are needed, even though they had to have been on the scene all along. One truly remarkable feat of physical genius occurs around page 42. Joan is in Blair’s apartment, coming to plead her case to him after the story he wrote. When a policeman comes to the door, Joan ducks into Blair’s bedroom, unready to give herself up. Fearful of the maid’s impending arrival, Blair tries to distract Police-Inspector Armstrong, to no avail. Two pages later, there is a knock on his outer door. It is Joan, disguised as her sister, ready to confront the law, heavy on her trail. But how? It is never explained.

There are parts of this tale, however, which concern matters mysterical and are equally amazing, and once explained, may very well take your breath away. It did mine, and for more reasons than one – one being pure audacity, and another – well, you’ll have to read this one for yourself.

Do I have room for another quote? I think so. From pages 84 and 85, where Pointer is telling Blair something about his philosophy of solving criminal cases:

“You know, you’re like the writers of these detective stories some people read – I can’t stand the drivel in ’em myself – who want you to suspect everyone near and far. The writers can’t help themselves, I see that, or how could they fill their books; but it’s not true to life! In a real case,†the Inspector went one confidentially, “of course, you look up everybody’s time-table and keep an eye on ’em – but there are some people you’re certain aren’t criminals. You’ve known ’em for years. You can leave ’em on one side – in your own mind. And there are others – well, you know they’re crooked at a glance, and you concentrate on them.â€

FOOTNOTE: Most of this research was done after this review was written, and this current first paragraph replaces several earlier ones dealing with what was known about A. Fielding in 2004. Check out this earlier post on this blog, and this review on Curt Evans’ blog, in the course of which he discusses the life of the author in much detail.

Sat 1 Feb 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

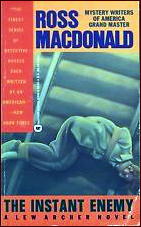

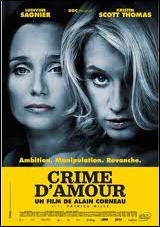

LOVE CRIME. French; original title: Crime d’amour, 2010. Ludvine Siegneur, Kristin Scott Thomas, Patrick Mille, Guillame Marquet. Directed by Alain Corneau, also co-screenwriter with Natalie Carter.

Love Crime may seem like a leisurely suspense film at the beginning, and granted it takes its time to establish the two main characters, but once it kicks into gear it is a fascinating character study with enough twists and turns to keep any fan of suspense films happy.

Kristin Scott Thomas has a showy role as Christine, a ruthless bisexual female executive who becomes mentor to the rather mousy Isabelle (Ludvine Siegneur). The sexual tension between them is obvious, and Siegneur, while shy, is not all that reluctant to be seduced. It becomes obvious this won’t end well early on.

Siegneur seems to slowly blossom under Thomas’s guidance, until things go south when Thomas sends Siegneur to Cairo on an important business trip. Siegneur seduces Thomas’s lover (Phillipe Mille), and pulls off a triumphant business coup that is certain to insure her quick movement up the corporate ladder.

Then Thomas takes all the credit for Siegneur’s coup.

A relentless no holds barred competition begins between the two women, played out in the boardroom and the bedroom. Blackmail, humiliation, and extortion all play a role in the game between them until Siegneur finds herself publicly humiliated by Thomas and firmly under her thumb again.

Aided unwittingly by her Iago, her assistant Daniel (Marquet in a perfectly under played performance), Siegneur begins a ruthless plan of revenge, but it seems more mad than anything else. Humiliated, she spins out of control into uppers and downers and what becomes increasingly obviously a plan to murder Thomas and doing her best to frame herself.

When she does murder Thomas, she even draws the first three letters of her name in Thomas’s blood. She is arrested and the police all too easily follow her self-incriminating trail. Still heavily drugged, Siegneur confesses. The film seems to be over, having driven itself into a wall.

I can’t say much more about the plot without giving too much away, but all is carefully unraveled as Siegneur’s true/false trail by turns leads the police in unsuspected directions. One by one as each pawn falls and each part of Siegneur’s plan is revealed, this worm-turns tale slowly reveals just how much the viewer as well as everyone else has been played by Siegneur from the beginning. She gives new definition to the term passive-aggressive.

Love Crime is handsomely shot in beautiful color and on sleek modern sets, and moves at such a deliberate pace you may not recognize this is the model of classic film noir, with two femme fatale’s in a cat and mouse game that mid-film turns into a Simenon psychological suspense story with enough twists for Agatha Christie.

It won’t be until the very last scene and the very last moment you realize how well you have been played, and how important that deliberation was to the final outcome of this clever film. Despite the two female leads don’t mistake this for a “woman’s” picture on Joan Crawford lines. This film is as hard and unsentimental a film as you will ever see.

The cast is uniformly good, but it is Siegneur and Thomas who carry the film and without either character ever becoming a really sympathetic character. Both have obvious personality problems and possibly borderline personality disorders. At one point in the film you will be convinced Siegneur is mentally unbalanced, a sociopath with an unhealthy obsession with Thomas. It’s not until the end you even begin to suspect the truth.

If you stay with this film you will find at the end you enjoyed it much more than you thought, and may even want to watch it again, to see if you can catch the places you were played, mislead, and bamboozled by the intelligent script. This film has the courage to ask you to stick with it, and rewards that effort with a final moment that will leave you frostbitten.

Love Crime was remade by Brian de Palma as Passion in 2012 with Rachel McAdams and Noomi Rapace. Despite that cast and a co-script by the screenwriter Natalie Carter, skip it and see the original, Corneau’s last film and a worthy one.

« Previous Page