April 2014

Monthly Archive

Sat 19 Apr 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

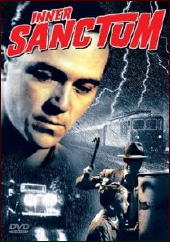

INNER SANCTUM. Film Classics, 1948. Charles Russell, Mary Beth Hughes, Dale Belding, Billy House, Fritz Leiber, Nana Bryant, Lee Patrick, Roscoe Ates. Director: Lew Landers.

I placed the DVD in the player, turned off the lights, grabbed some popcorn, and sat down to watch the Lew Landers-directed Inner Sanctum on an atypically cold spring New England night.

While it is certainly not one of the best-known films noir, Inner Sanctum has many of the genre’s elements: black & white cinematography with ample shadows, a murder, jealousy and betrayal, a woman (or two) scorned, a man at his breaking point, and a suspenseful plot with a clever, twist ending.

We begin with grainy footage of a train. On board sits a mysterious white-haired gentleman — an apparent clairvoyant psychic with a notable disdain for watches — who tells the woman seated next to him a cautionary tale about a woman who refused to heed a warning not to detrain.

The man, we learn, is named Dr. Valonius, although he is not a medical doctor. Portrayed by Fritz Leiber, Sr., father of the accomplished fantasy-science fiction author of the same name, Dr. Valonius overall remains dispassionately calm when telling Eve Miller (Marie Kembar) the story of a headstrong woman who after, disregarding a warning, got off a train when she shouldn’t have and got killed.

The heart of Dr. Valonius’s story, and of the film’s narrative, is about the dark psychological journey of her murderer. But with Inner Sanctum running at a mere 62 minutes in length, we never learn all that much Harold Dunlap (Charles Russell), except that he seems to be willing, for most of the movie at least, to do just about anything to not get caught.

As it turns out, however, Dunlap wasn’t totally alone on the train platform when he murders the woman. There was a witness to his chilling act. Sitting there, just watching trains, was a young boy, Mike Bennett (Dale Belding). While not a witness to the crime itself, Mike encounters Dunlap after the deed is done and notices blood on Dunlap’s suit jacket. It’s dark out, though, so maybe the kid isn’t seeing everything all that well.

The story follows the film’s anti-hero, Dunlap, as he maneuvers his way both physically and psychologically through the small Pacific Northwest town where he finds himself. Problem is, the town is experiencing extreme flooding and Dunlap can’t get out. He’s trapped.

After hitching a ride from a jocular overweight man named McFee (Billy House), Dunlap ends up staying at a boarding house. It’s filled with archetypical characters right out of central casting. Among them, a single mother who desperately wants a husband, a San Francisco beauty with a hidden past and a thing for dangerous men (Jean Maxwell portrayed by Mary Beth Hughes, best known for her role in the 1943 western, The Ox-Bow Incident), a drunk who likes his beer, and a precocious young boy—the same kid a blood-encrusted Dunlap encountered at the train station.

Dunlap’s relationships with Maxwell and with young Mike Bennett make up the central part of the film. Although he’s not guilt-ridden, he still has to make some choices to make. Is he going to run away with Maxwell or not? Is his secret worth killing over, even if it means killing Mike?

The film touches upon some quasi-philosophical questions, such as what does it mean for a good man to go bad, but hardly considers them in any meaningful depth. In many ways, there is very little redeemable about Dunlap. He’s definitely noir, rather than a shade of grey.

Part of this may have to do with Russell, who was less known as a film actor and better known as a radio actor, notably in CBS’s Yours Truly, Johnny Dollar. He portrays Dunlap as a paranoid, angry man. Indeed, in some spine chilling moments, he really does look crazed. But there’s not much range of emotion. Russell’s acts like angry and embittered man throughout the course of the film, making his performance, in a way, boring.

Dialogue in the film ranges from hackneyed to comedic and everything in between. The first time Dunlap tells Maxwell, “You’re very pretty when you’re lips aren’t moving†it’s both dark and comedic. The second time he says it, it’s laughable (and not in a good way).

But there are some absolute gems as well, such as when Dr. Valonius tells the woman on the train why he doesn’t wear watches: “I have no need for such contrivances†and “I once had a difference of opinion with a watchmaker. I’ve boycotted timepieces ever since.†Such brilliant weirdness!

Inner Sanctum is in no way a big budget film or a must see. It’s sort of like a parlor trick. It’s fun and you kind of want to know how the director pulls it off. But the acting isn’t particularly memorable and, apart from the train, the settings are generally forgettable.

But then, there’s Dr. Valonius. Even though he’s in the movie for less than five minutes in total, Leiber definitely steals the show. And even though most films noir don’t deal with supernatural themes, there’s something about an old psychic on a train that’s about as noir as noir can get.

Fri 18 Apr 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

BILL GULICK – Bend of the Snake. Houghton Mifflin, hardcover, 1950. Paperback reprints: Bantam #906, 1951; Paperback Library, 1968.

BEND OF THE RIVER. Universal, 1952. James Stewart, Julia Adams, Arthur Kennedy, Rock Hudson, Jay C. Flippen, Chubby Johnson, Stepin Fetchit, Harry Morgan Jack Lambert, Royal Dano, Frances Bavier. Screenplay by Borden Chase. Directed by Anthony Mann.

Bill Gulick’s first novel, Bend of the Snake, doesn’t seem like anything special to me, but it got snatched up immediately by the movies, and then discarded — of which more later.

Bend rides out slowly at first, with Scott Burton summoned to help out an old friend in a foundering business deal. Seems his buddy Emerson Cole is trying to break up a local monopoly in the Oregon territory and needs Burton’s help — understandable since Burton is that stock figure of Western Fiction: an honest man who can’t be beaten with guns or fists.

Gulick never tells us just what the bond is that makes Burton so willing to come to Cole’s assistance, but it quickly becomes apparent that Cole has neither the spine nor the ethics of his good buddy, character traits which lead the story into murder and a fairly well-handled investigation when a bookish youngster turns amateur sleuth.

For the most part though, this is pretty standard stuff, with Burton breaking the local robber baron by getting a load of goods to market past his hired guns, then beating down further attempts at ambush, arson and general mayhem.

Gulick creates an effective cast of salt-of-the-earth settlers and a crusty riverboat captain to give the tale a fine, spirited background, but plot-wise this is no different than a hundred others.

This was filmed, sort of, as Bend of the River, and when it came out Gulick ran an ad complaining that the only things they used from his book were the first three words of the title. Whereupon screenwriter Borden Chase observed wryly that he should have waited to see if the movie was a hit before distancing himself from it.

In fact, Bend of the River (the second teaming of director Anthony Mann and star Jimmy Stewart) was a big hit, and deservedly so. It is in fact, probably the most enjoyable of Mann’s westerns and the most satisfying of Stewart’s.

Just to be strictly accurate, I should note that Borden Chase did incorporate a few elements from Gulick’s book besides the first three words of the title: Emerson Cole is still a shifty character (though considerably more ballsy as played by Arthur Kennedy) and there’s still a helpful steamboat captain and something about getting a wagon load of goods past considerable obstacles, but the rest is pure Borden Chase, and it’s a theme he’d return to again: a man of principle (Jimmy Stewart, natch, the character re-named Glyn Mclyntock) allied with a helpful but not entirely trustworthy partner (Arthur Kennedy in a role he’d also return to again) involved in a deadly undertaking that is part thrill-a-minute adventure and part spiritual odyssey as Stewart/Mclyntock seeks to redeem himself from his past.

Mann seemed particularly attuned to this sort of thing and he evokes it here with speed and energy but without the angst that intensifies his later films: The Naked Spur (’53) and Man of the West (’58) may be more profound, but Bend of the River is more fun, as Stewart and Kennedy brave marauding Indians, crooked speculators, hired guns and mutinous miners (Morgan, Lambert and Dano at their best/worst) on their way to a confrontation that seems all the more satisfying because we know it’s coming.

I should also add that Universal had Chase write in a part for a rising young newcomer on the lot, Rock Hudson, who can be glimpsed in the Mann/Stewart Winchester ’73 (1950). Chase wrote him in but then apparently had no idea what to do with him as Hudson drops out of the action at a crucial moment and only reappears when it seems safe to do so.

Thu 17 Apr 2014

A Movie Review by MIKE TOONEY:

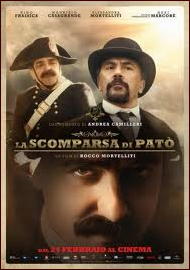

THE VANISHING OF PATÒ. Produced by 13 Dicembre, Emme, S.Ti.C., Rai Cinema, plus others. Premiered in Italy, 2010, as La scomparsa di Patò. Lead parts: Nino Frassica (Marshal Paolo Giummaro), Maurizio Casagrande (Delegato Ernesto Bellavia), Alessandra Mortelliti (Signora Elisabetta Mangiafico in Patò), Neri Marcorè (Antonio Patò), Alessia Cardella (Rachele Infantino). Writers: Andrea Camilleri (novel, screenplay), Rocco Mortelliti and Maurizio Nichetti (screenplay). Director: Rocco Mortelliti. In Italian with English subtitles (MHz broadcast).

It’s Easter Week, 1890, in the small Sicilian town of Vigata, and the place is abuzz with activity. The annual Mortorio passion play is well underway when one of the principal actors portraying Judas simply vanishes without a trace during the performance. The last anyone sees of him is when he falls through a trapdoor.

But this Judas is a pillar of the community — a mid-level bank manager named Antonio Patò, known to everyone for his devotion to work, church, and family.

Immediately a search is instituted headed by a big-city policeman (Delegato Ernesto Bellavia), but he’s having no luck whatsoever until a provincial policeman (Marshal Paolo Giummaro) gets involved.

As these two cops, completely different from one another, pursue their investigation they must find answers to such questions as: Why would a man who has been suffering from a rare African sleeping sickness suddenly, almost miraculously, get well practically overnight? Why would it take a man seven hours to make a forty-five minute trip? Who stole several articles of clothing backstage at the Mortorio, and later a pair of shoes from the steps of a church? Who was the man dressed as a farmer who bought a ticket with smooth, uncalloused hands?

Why would the corpse of a local “businessman” be found neatly laid out on a wall with his severed hands lying on his chest? Why would it become necessary for the two detectives to find themselves in a graveyard at midnight looking for just the right dead man to suit their purposes?

And perhaps most importantly, why won’t anyone — not the missing man’s wife, not the higher ups in the bureaucracy, NO ONE — believe our detective duo’s solution to this case? After all, it ingeniously explains every anomalous detail, overlooking nothing.

The answer to that last question is, of course, the essence of the story, the underlying satirical social commentary which the producers are aiming for.

While the movie isn’t really original — borrowing heavily from the buddy-cop theme seen in countless films, for instance — it’s the style more than the substance that kicks it up above the ordinary. Some reviewers fault the movie for the extended explanation sequence (over fifteen minutes) at the end, complaining that it’s too long. On the contrary, the big reveal here is perfectly logical and beautifully executed, with past and present seamlessly overlapping each other.

Novelist and screen writer Andrea Camelleri is best known for creating Inspector Montalbano, the subject of a long-running Italian TV series.

Viewers might recognize Nino Frassica from another series in which he also plays a marshal, Don Matteo.

Tue 15 Apr 2014

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

THE RETURN OF JIMMY VALENTINE. Republic, 1936. Re-released for TV as Prison Shadows. Roger Pryor, Charlotte Henry, Robert Warwick, James Burtis, Edgar Kennedy, J. Carroll Naish, Lois Wilson, Wade Boteler, Gayne Whitman. Director: Lewis D. Collins. Shown at Cinefest 26, Syracuse NY, March 2006.

This was one of those fast-moving programmers that play a lot better than many of the “A” films of the time. It immediately caught my interest with the on-screen re-creation of a Jimmy Valentine radio program that quickly becomes a newspaper sponsored “Find Jimmy Valentine” contest.

Naish is the leader of a gang looking for Valentine to help pull off a bank heist, while Burtis and Kennedy provide some comic relief. Charlotte Henry was a mature Alice in a 1933 version of Carroll’s classic; here, she’s an attractive leading lady, continuing a modestly successful ten-year film career.

Robert Warwick, a dependable, leading actor, is the legendary cracksman. He also played Jimmy in the silent Alias Jimmy Valentine, a film released in 1915 and directed by Maurice Tourneur

Mon 14 Apr 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

AGATHA CHRISTIE – The Man in the Brown Suit. Dodd Mead, US, hardcover, 1924. First published by John Lane/The Bodley Head, UK, hardcover, 1924. Reprinted many times since, in both hardcover and soft. First serialised in the London Evening News under the title Anne the Adventurous, 29 November 1923 to 28 January 1924 (50 installments). TV Movie: CBS, 1988, with Stephanie Zimbalist (Anne Beddingfeld), Rue McClanahan, Tony Randall, Edward Woodward (Sir Eustace Pedler), Ken Howard (Gordon Race).

While I am tempted to say that this is something of a departure by Christie, that would merely demonstrate my ignorance, as this is one of her earlier works.

Here she has written a thriller featuring an intelligent, on all but a few occasions, young lady who is seeking adventure. When Anne Beddingfield observes a supposed accidental death at a tube station and suspicious behavior by an alleged doctor, she connects this with a murder the same day. Soon she is spending her meager inheritance for a berth on the Kilmorden Castle, en route to South Africa, in pursuit of the alleged murderer, the Man in the Brown Suit.

Developments are revealed through the viewpoints of Beddingfield and Sir Eustace Pedler, M.P., both drolly and sillily, if there is such a word. Good fun and, incidentally, a forerunner to…

But you don’t want to know that, do you? I had that knowledge when I started the novel, and it didn’t spoil the pleasure. Other people may be less complaisant.

— From

The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Sun 13 Apr 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

DOROTHY M. JOHNSON – The Hanging Tree and Other Stories. University of Nebraska Press, softcover, 1995, with ten stories. Ballantine 274K, paperback original, 1957, with seven stories. Several later Ballantine printings.

The Hanging Tree is a collection of ten tales by Dorothy M. Johnson written from 1942-57 and some of the best western fiction I’ve ever read. Johnson could pack movement, character and setting into a very few words without sounding packed, and she knew how to develop a tale with a feel for its implications as well as its actions.

The result is ten memorable vignettes of which “The Hanging Tree” — a great story by itself — is perhaps the least. I got a lot of pleasure from “Lost Sister,” a cryptic tale of a “rescued” captive, and “The Last Boast,” in which a condemned cowboy looks back on the best-and-worst thing he ever did, and there’s some laugh-out-loud prose in “I Woke Up Wicked.”

In all, a book to treasure and a writer to seek out again.

Editorial Comment: For more on the author of this collection, Dorothy M. Johnson, her Wikipedia entry is a good place to start.

Sat 12 Apr 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

“NIGHTMARE AT 20,000 FEET.” Episode 123 of The Twilight Zone (CBS TV). Original air date: October 11, 1963. Starring William Shatner. Written by Richard Matheson. Directed by Richard Donner.

Much has undoubtedly been written about “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” an iconic Twilight Zone episode. The show, however, is well worth revisiting, particularly in light of writer Richard Matheson’s passing last year and of director Richard Donner’s recent announcement that he hopes to film a sequel to his 1985 cult classic, The Goonies.

This 25-minute black & white episode is not merely a vivid small screen representation of psychological torment. It also serves as an excellent reference point for those seeking to connect seemingly disparate elements of twentieth-century science fiction, horror, and popular culture, from airplanes to zombies.

The plot of “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” based on a 1961 Richard Matheson short story of the same name, unfolds as follows. A salesman named Robert Wilson, portrayed with great dramatic effect by a youthful William Shatner in his pre-Star Trek days, spots a bizarre creature — a gremlin — tampering an aircraft’s engine while the plane is in flight.

It’s a Twilight Zone episode, so of course there’s a twist. Months earlier, Wilson had experienced a “nervous breakdown†while on an airplane. Now, he is back on a plane for the first time since his stay in a sanitarium. Accompanying him is his wife, played by Christine White. But who is going to believe a man who has suffered from mental illness, especially when he’s the only one who sees the gremlin (Nick Cravat in furry suit that now looks more silly than scary) out on the wing, attempting to tamper with the plane?

Gremlins, of course, have not been the most prominent of monsters in twentieth-century popular culture. Unlike vampires and demons, which have a long pedigree, the notion of creatures called gremlins likely originated in the 1920s as the figment of British pilots’ collective imaginations. They were prone to mechanical mischief and blamed for tampering with aircraft.

The best-known literary work about these modernist monsters is Roald Dahl’s children’s book, The Gremlins (1943). Dahl, of course, would go on to write numerous children’s books, screenplays, and short stories.

Gremlins, of course, had their moment in the sun (pun intended), in the 1984 film, Gremlins. Written by Chris Columbus and directed by Joe Dante, with Steven Spielberg as the film’s executive producer, Gremlins went on to become an American cult classic.

In the Twilight Zone episode, the character of Wilson mentions gremlins during the flight and alludes to their role in tinkering with aircraft “during the War.†But the gremlin in “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is, in many ways, peripheral to the episode. It’s a human story, one that remains compelling to this day. It touches on the deep-seated human fear of being, or feeling, completely alone in the midst of chaos.

Sure, Wilson is with his wife, the pilot, and other passengers. But no one believes him. That’s when, of course, he decides to take matters on his own hands. Without giving away how the story ends, I’ll just mention that there’s an easily accessible gun on the airplane and the emergency window gets opened. Matheson’s story is still incredibly fresh. Optimists take note: there’s a redemptive aspect for Shatner’s character at the very end.

This leads me to the March/April 2014 issue of Famous Monsters, which includes an extensive tribute to the episode’s writer, Richard Matheson. In a compelling passage, Richard Christian Matheson, the author’s son, wrote as follows:

“My father could almost see to the core of others in a blink, undistracted by their presented selves. With a sleuth’s calm, he listened, and asked polite questions, until they wandered into the light, often relieved to finally be seen. That genuine curiosity didn’t judge, his empathy for human drama boundless. As a writer, his respect for mazes of human psyche deepened his characters, made them real.” (Page 7)

Although Richard Christian Matheson doesn’t specifically allude to any particular characters, I can see how this characterization of Matheson’s thinking could apply to the aforementioned Robert Wilson. Indeed, one can hardly watch Shatner’s performance without feeling for his character.

In conclusion, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is more than just a singular episode in the Twilight Zone corpus. It is a cultural artifact in its own right. Aside from Rod Sterling, a legend all his own, the three main men involved in this particular episode’s creation — Shatner, Donner, and Matheson — collectively went on to create a vast body of work that includes some of the best late twentieth-century works in science fiction and popular culture.

And even though the episode is over fifty years old and the gremlin looks a bit goofy, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is an extremely well-written story and an episode worth watching again, if you haven’t done so recently.

Reference: Famous Monsters #272, March/April 2014.

Thu 10 Apr 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

JUST OFF BROADWAY. 20th Century Fox, 1942. Lloyd Nolan, Marjorie Weaver, Phil Silvers, Janis Carter, Richard Derr, Joan Valerie, Don Costello. Screenplay by Arnaud d’Usseau, based on the character created by Brett Halliday and an idea by Jo Eisinger; photography by Lucien Andriot. Director: Herbert J. Leeds.

Lillian Hubbard (Janis Carter) is on trial for the murder of her fiancee Harley Forsythe, and despite defense attorney John Logan (Richard Derr) it doesn’t look good for her. Luckily for her newswoman Judy Taylor (Marjorie Weaver) and news photog Sam Higgins (Phil Silvers) are looking for a story, and private detective Michael Shayne (Lloyd Nolan) is on the jury.

It all opens with a bang, a witness, the English butler of a neighbor of Lillian Hubbard who can support her alibi, is murdered in the courtroom by a bearded man with a throwing knife. In the confusion Shayne hides the weapon under the prosecutor’s table. Merely being sequestered isn’t going to stop him from solving a case his own way — especially after he slips his sneezing roommate sleeping pills.

Though not based on a Brett Halliday novel, that high-handed way with clues is a trademark of Michael Shayne, who never met a piece of evidence he couldn’t improve, suborn, or otherwise play fast and loose with.

When Shayne goes to retrieve the knife he finds Judy spotted him hiding it and they are teamed in the investigation. They’ve been through this before. Shayne once proposed to her — just to get her out of his hair in another case.

The only thing he hasn’t figured out is how he is going to get paid.

Among the suspects are a leggy nightclub singer Rita Darling (Joan Valerie), the owner of the club where she works George Dolphin (Don Costello), and Count Telmachio, a professional knife thrower — not to mention the defense attorney who has long been in love with Lillian Hubbard.

Judy: Why are you always taking advantage of me?

Shayne: ’Cause you make it so easy.

Shayne gets knocked out searching the knife-thrower’s dressing room, then Judy and he follow the phony count where they find him murdered too.

Shayne: I was stickin’ my nose into something that don’t concern me and almost got it cut off.

Historically the Shayne films helped establish many of the tropes of the Hollywood private eye as much as any film or film series, and if only the first one was actually based on a Halliday novel, the others were taken from books by Clayton Rawson, Fred Nebel, Richard Burke, and Raymond Chandler’s The High Window (and a better version than John Brahm’s The Brasher Doubloon).

So far one collection of Shayne films has been issued by Fox on DVD containing Michael Shayne, Private Detective; Blue White and Perfect; Sleepers West (based on Fred Nebel’s Sleepers East; and The Man Who Wouldn’t Die (based on a Clayton Rawson Great Merlini novel).

As yet uncollected (and sadly unlikely to be) are Dressed to Kill (based on a Richard Burke Quinny Hite novel), Just Off Broadway, and A Time To Kill (based on Raymond Chandler’s The High Window). Dressed to Kill has shown up on at least one cable channel, but Just Off Broadway and A Time To Kill can only be found on the gray market.

Judy: John K. Smith? What does the K. stand for, Kluck?

Shayne: You know I used to be quite a dancer.

Stepping on Judy’s toe: When was that?

Shayne: Well, they changed the rules since the Charleston.

A dolphin brooch found near Telmachio’s body plays a key role in the case, especially when it turns out the jeweler (Francis Pierlot) who made it was once the father-in-law of the murdered man, whose daughter committed suicide over Forsythe’s cheating.

Meanwhile Shayne is busy ducking Sam Higgins who wants a photo of him to sell proving Shayne has snuck out on the jury giving Silvers plenty of excuses for quick patter and smart talk and Shayne a chance for some quick footwork.

Sheriff: Were you out of this room tonight?

Shayne: Who do ya think I am, Superman?

Shayne manages to outwit Silvers, but he still has to solve the case.

This is the least of the Shayne series, which isn’t that much of a knock. It’s rapidly paced and written and if the mystery isn’t exactly a headscratcher, it’s still fun to watch Nolan’s Shayne playing his usual games with the law and even getting a shot at playing Perry Mason when he acts as friend of the court from the jury box and questions the suspects before solving the case.

Richard Derr is best known for his role in George Pal’s film of the Philip Wylie-Edwin Balmer novel When Worlds Collide and also appeared in the Charlie Chan film Castle in the Desert. (Someone will have to confirm this, but I believe he was actually related to Charlie Chan author Earl Derr Biggers.) Late in his career he played Lamont Cranston, the Shadow, in The Invisible Avenger, minus the slouch hat and cloak, but with the power of invisibility and clouding men’s minds.

Marjorie Weaver appeared in most of the Shayne films though not always in the same role. She had good rapport with Nolan and their scenes have real zip.

Shayne does catch the killer and solve the case and ends up in jail for contempt of court for ten days — until Judy talks to the judge — getting him sixty days …

Better known for his villains (serious as in The Texas Rangers or comic as in The Lemon Drop Kid) and character parts (the doctor in Peyton Place, the father in Susan Slade) and for good cops (G-Men, Somewhere in the Night, Two Smart People, The House on 92nd Street) than as a leading man, Nolan was ideally suited to play Michael Shayne, and his Brooklyn accent mixed with an Irish brogue (throughout the series he’s accompanied by a jaunty Irish tune), mobile face, and well timed double-takes make his version of Michael Shayne the definitive one on screen even if he is nowhere near as dark or tough (or smart) as Halliday’s creation.

That may be, but for many of us Nolan will always be our Michael Shayne — even if he isn’t quite Brett Halliday’s.

Note: Shayne was played by Wally Maher and Jeff Chandler on radio; Hugh Beaumont in a poverty row series following Nolan; and Richard Denning (Mr. and Mrs. North) in a short lived series Michael Shayne, Private Detective that adapted many of the Brett Halliday novels to the small screen as Perry Mason had adapted many of Erle Stanley Gardner’s books. There is supposed to be a pilot film with Mark Stevens as Shayne that is tougher minded and closer to Halliday’s creation, but I’ve never been able to confirm if it was ever aired. Though without Shayne, the Robert Downey/Val Kilmer film Kiss Kiss Bang Bang was based on a Halliday novel and one of the episodes of the trilogy film Three Cases of Murder is based on a non-Shayne short by Halliday.

Wed 9 Apr 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

JEREMIAS GOTTHELF – The Black Spider. New York Review of Books, paperback, 2013. Translated by Susan Bernofsky. First published as in German as “Die schwarze Spinne” in 1842.

When I first spotted a new copy of Jeremias Gotthelf’s The Black Spider in the science fiction/fantasy section of my favorite Washington D.C. bookstore, I confess that I wasn’t familiar with either the author or the book.

My curiosity was piqued, so I decided to purchase the novella. I’m glad I did. I read it over the course of several days, scribbling notes to myself on the margins, and I found myself eager to learn more about the life and times of Albert Bitzius (1797-1854), the Swiss pastor and novelist who, under the pen name of Jeremias Gotthelf, wrote one incredibly vivid and didactic horror tale.

The Black Spider begins with a serene pastoral Swiss setting. A family and their friends have gathered for a child’s baptism. All seems well in the world. Then one member of the baptismal party notices something odd. There’s a black piece of wood in the old house’s window post that’s noticeably short and out of place. People are curious. What is this piece of wood doing there? As the old advertisement used to say, inquiring minds want to know.

That’s when the action really takes off. The grandfather (unlike in Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague, we never learn his proper name) uses the piece of black wood as a jumping off point to tell a haunting tale about a castle, a brutal knight named Hans von Stoffeln of Swabia, oppressed peasants, and woman named Christine of Lindau who tries to outsmart the Devil. As if that weren’t enough, there’s also a sinister quasi-sentient demonic arthropod that wreaks all sorts of havoc and mayhem.

The basics of the story are as follows. Some six hundred years ago, a cruel knight forces his peasants to relocate some beech trees in order to create a shady walk by his castle. They have no idea how they are going to complete such a physically demanding task.

Enter a strange character, a huntsman dressed in green, with a red feather in his cap, and a red beard. It’s not too long before the reader learns that this huntsman has the stench of sulfur about him. Soon after, we learn that he’s the Devil. The aforementioned Christine makes an unholy bargain with him, one that would allow the villagers to be freed from the nearly insurmountable burden of planting the trees. The deal is sealed with a kiss on the cheek. But, as with all deals with the Devil, it comes at a steep price. In this case, the Devil wants the villagers to turn over a newborn child before it is baptized.

Without giving too much of the plot away, suffice it to say that Christine’s choice isn’t the wisest one. Soon, there’s a strange black dot on her face. Sooner still, it morphs into something far more grotesque and spine chilling:

“But Christine was not lighthearted. The closer the day of the birth approached, the more terrible the burning in her cheek became, and the more the black spot swelled, stretching distinct legs out from its center and sprouting tiny little hairs; shiny points and stripes appeared on its back, the bump became a head, and from it flashed glinting, venomous glances, as if two eyes. Everyone shrieked at the sight of this venomous spider upon Christine’s face, rooted in her face, growing there, and they fled in fear and horror.†(pp. 53-54)

After that, things get even weirder. The black spider comes to life and brings death. Eventually, a woman captures the spider and plugs it in a hole. There it rests for many years. Then, in an age of impiety and frivolity, the spider gets loose again. Only this time, there’s a man named Christen who, with divine assistance, is able to “thrust the spider into the ancient hole.†(p. 102).

Here, the religious message of the work becomes increasingly apparent. Faith and honesty are good; “pride and vainglory†are bad (p. 105). And as far as the aforementioned piece of black wood, it gets incorporated into the frame of a newer house and keeps the black spider imprisoned, where it supposedly remains on the day when the grandfather tells the baptismal party this very creepy story.

Early nineteenth-century Switzerland doesn’t immediately come to mind when one thinks of either Gothic fiction or what is best described as weird fiction. Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, and H.P. Lovecraft were all twentieth-century writers and wrote their works in an increasingly secular world. Jeremias Gotthelf, by contrast, was a more devout man who wrote in an age more steeped in faith than the aforementioned purveyors of cosmic horror. His ultimate villain was the Devil, not some strange creature from beyond space and time.

But then again, there’s the bizarrely sentient black spider. If one reads the work critically, one sees that the author’s description of the spider at times reads less like something out of a fairy tale or a religious novella than it does out of an early twentieth-century pulp magazine:

“The crowd flew apart, all eyes drawn to the foot to which the hand of the screaming man was pointing. On this foot sat the spider, black and huge, glowering balefully, maliciously all around. The blood froze in their veins, the breath in their breasts, and the sight in their eyes, while the spider calmly, maliciously peered about, and then the man’s foot turned black, and in his body it felt as if fire were hissingly, furiously doing battle with water; fear burst the bonds of horror, and the crowds scattered.†(p. 72)

The Black Spider may very well be one of the first works of weird fiction ever written. For this reason, it’s well worth reading. But it’s also a good scary tale to read on an overcast day when it’s windy outside, the rain is hitting your windows, and you have some cabin fever. That’s what I did. And I loved every minute of it.

Mon 7 Apr 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

AUSTIN LEE – Miss Hogg and the Missing Sisters. Jonathan Cape, UK, hardcover, 1961. No US edition.

The elderly ladies who live next door to Alan Johnston, middle-aged author of historical novels, have written a book about the old days in Ireland and are worried about parts of it perhaps being libelous. Thus they seek Johnston’s advice. Before he can read much of the book, his neighbors disappear and the manuscript is the only item taken from his house during a burglary.

In addition, in the same neighborhood a death, possibly murder, with seemingly no connection to the disappearance or the burglary, has taken place. Johnston consults Miss Hogg, B.A., Private Investigator, and he, she, and Miss Hogg’s friend, Millie, travel to the elderly ladies’ childhood home, with both good and bad results.

This novel takes place near the end of Miss Hogg’s career as a private investigator — it is the penultimate; the final one is fittingly titled Miss Hogg’s Last Case — and contains little about her as an individual. Her first name is an aberration on her mother’s part, she says, and she prefers to be known as ‘Hogg, tout conn. ” Her given name is revealed, though not by her, as Flora, about which someone remarks, I must say that Miss Hogg did not immediately suggest to one the goddess of the spring.”

Whether Miss Hogg can be placed in the little-old-lady-detective category, I cannot say since her age is not provided. She is a former schoolteacher, but not as far as I could tell a retired one. Johnston, whose views are more elderly than he, makes for a somewhat amusing narrator.

On the other hand, Miss Hogg really doesn’t come alive, the plot is minimal, and the murderer and the motive are patent. Nonetheless, while Austin Lee’s name is not going on my list of authors to look for, should I come across another of his Miss Hogg novels serendipitously, I would not hesitate to read it.

Since Hubin’s bibliography does not mention it and there might be those who would like to know, I’ll note that Austin Lee was a clergyman.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

The Miss Flora Hogg series —

Sheep’s Clothing. Cape, 1955.

Call in Miss Hogg. Cape, 1956.

Miss Hogg and the Bronte Murders. Cape, 1956.

Miss Hogg and the Squash Club Murder. Cape, 1957.

Miss Hogg and the Dead Dean. Cape, 1958.

Miss Hogg Flies High. Cape, 1958.

Miss Hogg and the Covent Garden Murders. Cape, 1960.

Miss Hogg and the Missing Sisters. Cape, 1961.

Miss Hogg’s Last Case. Cape, 1963.

« Previous Page — Next Page »