May 2014

Monthly Archive

Wed 21 May 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

OLIVER WELD BAYER – Paper Chase. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1943. No paperback edition. Film: MGM, 1945, as Dangerous Partners.

According to The Crime Club, this is a “fast-paced mystery by a new writer who offers speed, humor, and one of the cleverest plot twists ever to appear in a mystery story.” One does wonder whether a fast-paced mystery could be achieved by a writer who doesn’t offer speed, but never mind.

On the subject of humor, of which I understand little, I yield reluctantly to those who think witless people in unusual situations, particularly characters beyond their depth, provoke mirth. Finally, if there is a clever plot twist, it escaped my, by the end of the novel, numb attention. Another point is that this book was serialized in Liberty, [a magazine] not noted as I recall for its departures from the norm.

After a plane crash, a confidence couple, man and wife, adopt Albert Mercer and his collection of four wills of which he is executor and beneficiary. When Mercer goes to Cleveland, he discovers that one of the will-makers is planning to write another in which Mercer does not figure. A statue topples on the will-maker, creating suspicion in the mind of his attorney, Jeff Piper, who is trying to get into Air Force Intelligence. Which he did, and how we won the war under that handicap is beyond my comprehension.

Piper teams up with Elizabeth Neff, detective-story novelist, who has a low opinion of her own books. Together they bumble through an investigation of the confidence couple and— But maybe that’s the clever plot twist and I shouldn’t mention it.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Bibliographic Notes: Information taken from Crime Fiction IV, by Allen J. Hubin. No recurring characters.

BAYER, OLIVER WELD; pseudonym of Eleanor Rosenfeld Bayer, (1914-1981) & Leo Grossberg Bayer, (1908-2005)

Paper Chase. Doubleday 1943

No Little Enemy. Doubleday 1944

An Eye for an Eye. Doubleday 1945

Brutal Question. Doubleday 1947

The film exists. Starring are James Craig, Signe Hasso, Edmund Gwenn and Audrey Totter. Has anyone seen it?

Tue 20 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

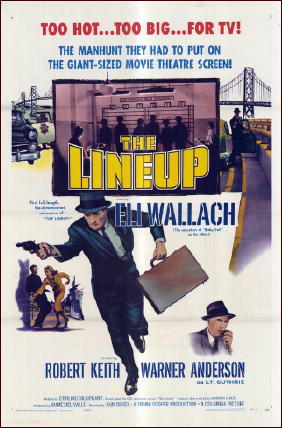

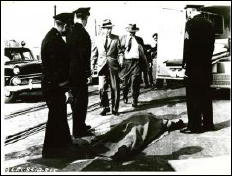

THE LINEUP. Columbia Pictures, 1958. Eli Wallach, Robert Keith, Richard Jaeckel, Mary LaRoche, William Leslie, Emile Meyer, Marshall Reed, Raymond Bailey, Vaughn Taylor, Warner Anderson. Screenplay: Stirling Silliphant. Director: Don Siegel.

The Lineup is a visually captivating thriller set in the historic buildings and on the daytime streets and roadways of San Francisco. It stars Eli Wallach (The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly), in one of his earliest big screen roles, as a Brooklyn-accented sociopathic hired gun for an international heroin smuggling operation.

Directed by Don Siegel (Dirty Harry), The Lineup is best interpreted as two distinct films wrapped together in one package. Indeed, the film, based on both a CBS radio show (1950-1953) and television show (1954-1960) of the same name, is two movies in one: a formulaic, somewhat forgettable, police procedural and a very good, albeit under-appreciated, film noir. It’s the story of a disturbingly violent, and somewhat pathetic, criminal on the margins of polite society, a man whose own unbridled rage propels him to his inevitable doom.

The film begins as a standard police procedural, opening with a fast-paced action sequence near the San Francisco docks. A porter throws a suitcase into a cab that promptly, and recklessly, speeds away, ramming into a truck and killing a police officer in the process. Lt. Ben Guthrie (Warner Anderson, reprising his role in the TV show) and his partner, Inspector Al Quine (Emile Meyer) are called on to investigate.

Neither of the characters come across as particularly devoted to the task at hand, although Anderson’s portrayal of a detective is far more engaging than is Quine’s. But the movie isn’t really about them — more on that in a minute.

The two San Francisco cops discover that the cab driver was part of a heroin smuggling operation and that an international cartel is utilizing unsuspecting passengers from East Asia to smuggle heroin into the United States. One such passenger is Philip Dressler (Raymond Bailey), a prominent member of San Francisco society employed at the architecturally impressive San Francisco Opera House. Dressler is called into the police station to witness a lineup, but he doesn’t recognize the porter who yanked his suitcase from his arms and threw it into the cab. Still, it’s not long until the porter shows up dead.

The film quickly shifts gears from a police procedural to a film noir about two hit men tasked with finding — and killing — other passengers who inadvertently smuggled heroin into the United States and to deliver the dope to a criminal known only as The Man (Vaughn Taylor), a real piece of work who only appears on the screen for a several minutes.

We first see the film’s protagonist/anti-hero, the brutal hired gun Dancer (Wallach) sitting on an airplane with his partner and mentor, the incredibly creepy Julian (Robert Keith). Dancer is reading a book of English grammar in an attempt to learn how to properly use the subjunctive tense so as to sound less like a New York gangster. This, of course, was Julian’s idea. Somewhere along the way, Julian made Dancer his pet project and clearly wants to smooth over the killer’s rough edges.

The men arrive in San Francisco and are quickly greeted by their driver, Sandy McLain (Richard Jaeckel). The three men, all losers each in their own way, successfully track down the first two carriers. It’s when they are tasked with retrieving the heroin from a woman, Dorothy Bradshaw, and her daughter Cindy that things, in classic noir fashion, all fall apart. The turning point in the film occurs when Dancer wants to kill Bradshaw and is stopped from doing so by Julian.

Wallach is simply excellent in this film. He portrays Dancer, a man born of rage and without a relationship with his father, convincingly. Watch throughout for his Dancer’s eye, and facial, expressions, particularly during his showdown with The Man in Sutro’s Museum.

Keith is equally convincing in his portrayal of Julian, a bizarre man who enjoys jotting down the last words people say before they die. In a one remarkably unsettling scene that shows characterization, Julian, upon seeing his female hostage weep, bursts out with his own self-serving pseudo-intellectual rhetoric. It’s not so much his misogyny that’s appalling; rather, it’s that he actually seems to believe his own nonsense:

“See, you cry. That’s why women have no place in society. Women are weak. Crime’s aggressive and so is the law. Ordinary people of your class—you don’t understand the criminal’s need for violence.â€

She replies (how else could she reply?): “You’re sick.â€

But as The Lineup shows us, that type of criminal sickness has real consequences. By the time the movie ends with a dramatic car chase on the unfinished Embarcadero Freeway, both Julian and Dancer, not to mention The Man, are dead, with their own character flaws playing significant roles in their not particularly tragic demises. Although the film takes place during the day rather than at night, it’s noir at its very best.

Mon 19 May 2014

THE ARMCHAIR REVIEWER

Allen J. Hubin

JOHN MALCOLM – The Wrong Impression. Scribner’s, hardcover, 1990. No US paperback edition. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1990.

The seventh of John Malcolm’s tales about Tim Simpson is The Wrong Impression, one of the more intense in this good series. Tim corrals works of art for a London bank’s investment fund, and has been instructed to track down (at affordable prices) a couple of impressionist paintings — a Monet, perhaps.

But there are bad times for Tim: his friend Inspector Nobby Roberts lies at death’s door from a shooting. The police seem at a loss, but determined that Tim will not conduct the independent investigating that he’s equally determined to do. This leads to an explosive rift in Simpson’s relationship with Sue Westerman, his live-in woman.

This part — Sue’s behavior — is not to me credible; she seems to have taken leave of her senses. But otherwise Wrong Impression is full of good stuff.

— Reprinted from The MYSTERY FANcier,

Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

The Tim Simpson series —

1. A Back Room in Somers Town (1984)

2. The Godwin Sideboard (1984)

3. The Gwen John Sculpture (1985)

4. Whistler in the Dark (1986)

5. Gothic Pursuit (1987)

6. Mortal Ruin (1988)

7. The Wrong Impression (1990)

8. Sheep, Goats and Soap (1991)

9. A Deceptive Appearance (1992)

10. The Burning Ground (1993)

11. Hung over (1994)

12. Into the Vortex (1996)

13. Simpson’s Homer (2001)

14. Circles and Squares (2003)

15. Rogues’ Gallery (2005)

Sat 17 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

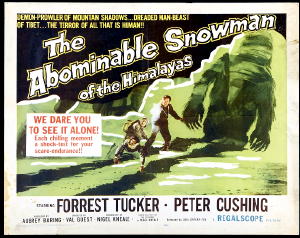

THE ABOMINABLE SNOWMAN. Hammer Films, UK, 1957. Released in the United States as The Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas. Forrest Tucker, Peter Cushing, Maureen Connell, Richard Wattis, Robert Brown, Michael Brill, Wolfe Morris, Arnold Marlé, Anthony Chinn. Screenplay: Nigel Kneale, based on his 1955 BBC teleplay entitled The Creature. Director: Val Guest.

Running just over 90 minutes, The Abominable Snowman stars Peter Cushing (Dracula, The Mummy) as an English botanist on an ill-fated Himalayan expedition to find the mythical Yeti.

The film is, in many ways, more of a psychological thriller than a traditional horror film. Both the claustrophobic isolation of the Himalayas and the tension between members of the expedition party play far more prominent roles in the narrative than do the Yeti, whom we see only briefly toward the end of the film.

The plot is relatively straightforward. John Rollison (Cushing) and his wife, Helen (Maureen Connell) are living and working in the Tibetan monastery, Rong-ruk. They are guests of the enigmatic Lama (Arnold Marlé) who seems to know a lot more than he lets on. Although Rollison isn’t in the best physical shape in the world, he insists upon joining the expedition of the loud-mouthed American guide and showman, Tom Friend (Forrest Tucker). Helen isn’t happy about the arrangement.

The party’s goal is find the Yeti. But Friend and his associates have different goals than Rollison. Friend, a conman and a fraud, wants to capture a Yeti alive and sell it to a carnival show. Rollison, more pure of heart, wants to study and learn about the Yeti.

He posits both that Yeti are intelligent, sentient creatures and that they are merely biding their time on Earth, hidden up in the Himalayan peaks, until man destroys himself. They also have quasi-hypnotic powers.

The doomed explorers do manage to find and to kill a Yeti, setting into motion a chain of events that leave Rollison the sole surviving member of the expeditionary party. The most important scene in the movie occurs in an ice cave when Rollison finally encounters live Yeti. He makes eye contact with one of them and realizes that his theory about Yeti intelligence was indeed correct.

The film, a product of the anxieties of the Atomic Age, imparts a fairly obvious message about how man’s hubris may end up being his downfall. The theme of what it means to be civilized also features prominently in the film. This is notable given the fact that the late 1950s were the beginning of the end for British imperialism.

While I would not go so far as to say that The Abominable Snowman is a particularly notable film, I found the story about how the Yeti will be man’s successors to be thought provoking. Unfortunately, the production quality now seems considerably dated.

The film’s pacing can feel a bit slow. Indeed, unlike The Mummy (also from Hammer films two years later and reviewed here earlier on this blog), which remains an absolute gem, The Abominable Snowman, while not a bad film, really doesn’t stand up to the test of time. Perhaps that is one reason why, in late 2013, Hammer Films announced that they are planning to remake this oft-neglected British cult classic.

In conclusion, The Abominable Snowman is certainly worth watching at least once, if only for the ominous Eastern-themed music, bells, and chants that provide the film with a strong fosters a sense of both wonder and of impending doom. The monastery setting, which features considerably in the movie, is also visually stunning. It’s a reminder that the film was meant to transport the viewer into a different realm of existence and human understanding.

While I probably won’t watch the 1957 version again any time soon, I’m quite looking forward to seeing how the forthcoming remake turns out. I only hope the filmmakers do make it more of a psychological thriller than a creature feature.

Fri 16 May 2014

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

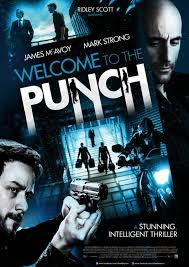

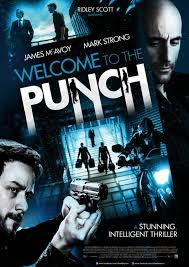

WELCOME TO THE PUNCH. IFC Films, 2013. James MacAvoy, Mark Strong , Peter Mullan, Johnny Harris, David Morrissey. Written and directed by Eran Creevy.

This Brit neo-noir bristles with violence, moral ambiguity, hard driving atmosphere, shadows, and edgy camera work, but like the best of the British crime films it is driven by character. The people are not violent cartoons, but human beings. The heroes are flawed and the villains all too human.

The film opens with hard-driven London detective Max Lewinsky (James MacAvoy) catching a high end heist. Against orders he pursues the gas-masked villains on motorbikes even though he is unarmed. That ends badly with Max knee-capped by the leader or the team, Jacob Sternwood (Mark Strong).

Years later Lewinsky is in constant pain and addicted to pain killers, but still a cop, working with his partner and lover Sarah (Andrea Risenborough) on a case involving arms smuggled into England, assigned by his friend Metropolitan Police Commander Thomas Geiger (David Morrissey). When a low level street hood, Ruan Sternwood (Elyes Gabel), is killed in relation to the case, Max knows it will bring his long-since-missing father back for revenge, and his chance to bring him down.

Sternwood shows up wanting revenge, and with the help of his old friend Roy Stewart (Peter Mullan) sets himself up with the men who killed Ruan. Soon he and Max find themselves alone against para-military killers with powerful connections and Max finds he was assigned to the case to fail.

When Dean Warns (Johnny Harris), one of the para-military killers, murders Sarah because she is onto something, Max and Sternwood find themselves allied with one goal: vengeance.

Welcome to the Punch moves quickly, and depends on strong performances with MacAvoy and Sternwood sketching in their relationship without a lot of extraneous dialogue. Nothing is spelled out in long-winded speeches, but is shown instead in their faces and actions. MacAvoy in particular brings a great deal of nuance to his wounded, angry, but honest policeman. Neither he, nor Strong are playing supermen for all their skills, and the shootouts have actual suspense because they are very human targets. The “Punch” of the title is a loading dock where the final odds against survival shootout takes place.

They do survive bullet wounds that in real life would throw them into instant shock and likely kill them, but at least they are more than the famous flesh wound of a million cowboy pictures, and you can just buy that adrenalin might get them through to the end in the real world. If you truly did one of these realistically, the film would be a one-reeler, mostly watching the hero bleed out in ten minutes or less, if shock didn’t kill him first, while he lay on the ground in a semi-conscious stupor.

These kinds of action films are no more realistic than comic book, fantasy, western, and science fiction films, and it is equally pointless to hold them to the standards of realism (or any film for that matter). This is no more the real world than a Fred Astaire musical is. At best film and literature create an illusion of reality, and you buy it or not.

The complex plot behind all the violence hardly matters, but is filled in enough to cover the action and provide a suitably large conspiracy for the two loners to confront. There is enough at stake to make the conspiracy seem plausible, yet not so much it is improbable two violent men couldn’t bring it down once they know who the key players for.

This is no cop-buddy film, not a British 48 Hours, or anything like. Max and Sternwood are drawn together by their loss, rage, and desire for revenge, but though they might respect each other, there aren’t going to be any hugs at the end of the film. There may be a brief moment when they recognize uncomfortably that they are more alike than not, but they are far from bosom buddies.

I don’t want to oversell this, you are likely better off to catch it on cable, Red Box, or Netflix it than pay through the nose to see it in a theater, but it is a well thought out and acted action film. It’s no Lock Stock and Smoking Barrel, Get Carter (the Michael Caine original), Long Friday Night, Mona Lisa, or even the belly laugh cop buddy send up Hot Fuzz, but it is fast paced, stylishly shot, and it won’t insult your intelligence.

There are no surprises, it is all predictable, but it is also marked by the good acting, script, direction, and action, all handled with nary a hitch, and you won’t come away from it with your seat numb because it ran on forever.

There is something to be said for a film that does what it sets out to with success whether it is innovative and new or not, and the cinematography by Harry Escott is sharply done.

If you watch it and like these kind of movies you will likely enjoy Welcome to the Punch quite a bit. It’s a well done gritty action film that has more brains and heart than many films like it with bigger stars, credits, and budgets.

Thu 15 May 2014

THE BACKWARD REVIEWER

William F. Deeck

JOAN COGGIN – Who Killed the Curate? Hurst & Blacken, UK, hardcover, 1944; paperback reprint, no date. Rue Morgue Press, US, softcover, 2001.

At first sight, and at second and third I would argue, Lady Lupin Lorrimer would seem an unlikely person to become the wife of a clergyman. At twenty-two she is a social butterfly, indeed possesses the brain of that creature, one moreover that was dropped on its head when it was a baby. But marry she does, to the Rev. Andrew Hastings, vicar of Glanville, somewhere on the English coast.

With no preparation, Lady Lupin is thrust into the parish’s affairs — the Mother’s Union, the Girl Guides, Foreign Missions — of which she knows little, that usually in error, and learns less. She also has to deal with the death of the parish’s curate, who may or may not have died from eating fish at the vicarage. Sort of a dimwitted Pamela North, Lady Lupin, along with her friends, becomes embroiled in the investigation.

Not a particularly good mystery, but a quite amusing novel.

— From The MYSTERY FANcier, Vol. 13, No. 2, Spring 1991.

Editorial Note: For a long informative essay on the life of Joan Coggin, check out the Rue Morgue Press page for her on their website here. In recent years Rue Morgue has published all four of the titles below, each one for the first time in the US.

The Lady Lupin Hastings series —

Who Killed the Curate? Hurst 1944.

The Mystery of Orchard House. Hurst 1947.

Why Did She Die? Hurst 1947.

Dancing with Death. Hurst 1949.

Wed 14 May 2014

REVIEWED BY WALTER ALBERT:

BRONCHO BILLY AND THE BABY. Essanay, 1915. G. M. Anderson (Broncho Billy), Berenice Sawyer, Evelyn Selby, Lee Willard. Based on a story by Peter B Kyne. Director: G. M. Anderson. Shown at Cinefest 26, Syracuse NY, March 2006.

It’s a strong sign of the popularity of the Broncho Billy series (and possibly, also, a symptom of the difficulty in getting new scripts fast enough to accommodate the rapid shooting schedules of the series) that this remake of Broncho Billy and the Sheriff’s Kid was released only two years after the original film.

Billy, an outlaw on the run, rescues a child and returns her to her mother. When the husband returns and discovers that the saviour of his child is a wanted outlaw, he’s faced with a moral crisis.

It’s difficult to explain the appeal of these simplistic little two-reelers, but they undoubtedly reside in guilelessness and sympathetic portrayal of Billy by Anderson, and in the emotional tug of the simply defined story lines.

The screening of an interview with Anderson by William Everson in 1957 showed Anderson to have a phenomenal recall of details of the early days of the film industry, if somewhat less appreciation of current films.

This was followed by Shootin’ Mad (1918), an abridged version of one of Anderson’s last Broncho Billy films, originally released as a five-reeler. The budget was larger so that the sets didn’t shudder when a door was slammed, but Billy was his dependable self, still, as the program notes put it, “a surefooted cavalier who turns into a bumbling clod when he meets a purty girl.”

Editorial Comment: The popularity of the Broncho Billy series (1910-1918) should not be underestimated. The list of films in the series on IMDb includes 144 of them, and there are quite likely many others that are missed.

Tue 13 May 2014

Posted by Steve under

Reviews1 Comment

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

C. S. HARRIS – What Remains of Heaven. New American Library, hardcover, November 2009; trade paperback, August 2010. Signet-Obsidian, paperback, August 2011.

If all you know of Regency England are rakes and ladies, duels and male vanity, Jane Austin and Georgette Heyer, then you may be surprised by this fairly dark mystery by C. S. Harris, a historian with an eye for the telling detail. There are no faughs or deuced clevers and no Scarlet Pimperneling, and our handsome hero is balanced by the attractive but annoyingly independent Miss Hero Jarvis who has a taste for women’s sufferance a good eighty years too early for Regency society. She isn’t the fainting type, and he’s a Regency rake with an annoying conscience.

A former soldier, Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount of Devlin (a viscount is a cousin of royalty) was introduced along with Hero in What Angels Fear and this is their fifth outing. Here the controversial reformer the Bishop of London is found in a crypt murdered by the body of an unknown victim of of a murder decades earlier.

St. Cyr is in no hurry to take up a case — his last one estranged him from his father for a year, and they are only now mending fences — but his aunt, the Duchess of Clairborne, shows up at his Brooks Street rooms with the Archbishop of Canterbury in tow wanting him to investigate, as his aunt snidely informs him: “Because your good at it, of course.â€

So St. Cyr is stuck joining forces with Bow Street magistrate Sir Henry Lovejoy in digging around the crypts looking for clues while Paul Gibson, ex-army doctor with a surgery in Tower Street, examines the body since “nobody knows more about dead bodies …â€

Meanwhile St. Cyr’s father the Fifth Earl of Hendon, current Chancellor of the Exchequer, has been approached by the Regent to form a government, which will throw him again into conflict with a powerful enemy the king’s physically and politically powerful cousin Charles, Lord Jarvis.

And all St. Cyr has to work with is Tom, his thirteen year old sharp faced protege and aide, and of course Hero, the daughter of Lord Jarvis and the Prince Regent’s greatest enemy. And just to complicate things, Hero is pregnant with St. Cyr’s child and heir.

The stage set St. Cyr sets about some creditable detective work in a Sherlockian vein — St. Cyr, we are told, is tall, lean, and possessed of “feral yellow eyes†— as a not so simple murder winds back thirty years earlier to the days of Sir Francis Dashwood and the infamous Hellfire Club as well as to the government in contemporary Whitehall.

Action, atmosphere, politics, genuine detective work, a historically accurate and beautifully drawn portrait of a fascinating era, smart likeable heroes, dangerous conspiratorial villains, and a desperate murderer driven by fear. What more could you ask for?

Noble families, including St. Cyr’s own, prove to have desperate secrets to keep, the government may not want certain things brought to light, there is a ruthless killer on the loose, the romantic subplot spins out of control, and St. Cyr proves to be a likeable if reluctant and somewhat roguish swashbuckling sleuth perhaps just a little over-matched by Hero Jarvis, who is not looking to trade a father for a husband even if she is with child.

Will Thomas, author of the Barker and Llewelyn novels, called Harris last a “ripping read,†and if you know his work he is no shirker at ripping reads himself. This has a little bit of everything, and I am certainly going to look into the other books in the series.

Harris also writes contemporary thrillers as C.S. Graham, and I’ll be looking for those as well. While her plot and style are not Carrian and she eschews miracle problems, at her best the atmosphere, historical accuracy, mysteryfying, and well drawn characters true to their time — all remind me of John Dickson Carr’s better historical mysteries, no small praise from me.

The highest recommendation I can personally give a book is ‘Damn good read.†What Remains of Heaven is a damn good read.

The Sebastian St. Cyr series —

1. What Angels Fear (2005)

2. When Gods Die (2006)

3. Why Mermaids Sing (2007)

4. Where Serpents Sleep (2008)

5. What Remains of Heaven (2009)

6. Where Shadows Dance (2011)

7. When Maidens Mourn (2012)

8. What Darkness Brings (2013)

9. Why Kings Confess (2014)

Mon 12 May 2014

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

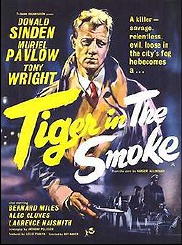

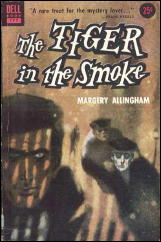

TIGER IN THE SMOKE. J. Arthur Rank, UK, 1956. Donald Sinden, Muriel Pavlow, Tony Wright, Laurence Naismith and Beatrice Varley. Screenplay by Anthony Pelissier, from the novel by Margery Allingham. Directed by Roy Ward Baker.

First off, you should know that I watched this quite by accident. Maybe even by mistake; after reading Never Come Back, I ordered the movie supposedly made from it (Tiger by the Tail) but the dealer sent me this instead — and I’m very glad he did.

Fans of Margery Allingham (I know you’re out there; I can hear you knitting your tea-cosies) may be disappointed to find that the makers of this film dispensed completely with Albert Campion, but lovers of tricky, off-beat movie-making will be delighted by it—or at least the first half, which opens with a visual symphony worthy of Welles or Vorkapich.

It’s all set in a thick London smog, through which the characters pursue one another, appearing and vanishing at odd moments, lurking half-seen, or unseen, or maybe-seen with eerie precision. Director Baker (or maybe Cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth deserves the credit) knows just when to generate suspense by looming a shifty shape up in the background, and just when to lose it in the mist. And there’s a remarkably fine extended business with a band of sinister performing street beggars, who wander in and out of frame in movements that look to have inspired the opening stretch of Touch of Evil.

The film itself is as intriguing plot-wise as visually: As the story opens, Meg Elgin (the delightful Muriel Pavlow) is being escorted by the police to rendezvous with a mystery man who may be her presumed-dead-in-the-war husband. Her helpful/hopeful fiancé (Donald Sinden) is also along, as the party make their way through the treacherous smog, dogged by those oddly menacing (and horribly off-key) street performers, and discover that the man who arranged the meeting is an only actor who resembles her late husband — but he’s wearing the dead man’s coat!

From here things diverge, with Sinden trailing the actor and getting caught up with the malignant cacophonists, while Pavlow and the cops try to find out how the actor got the coat. Along the way we find that a bad guy called Jack Havoc has broken jail and is out there searching for… we don’t know for what yet, but we do know it has something to do with the late husband, and Havoc is willing — even eager — to kill for whatever it is. As one of the detectives comments, “He’s pure evil.â€

Eventually Jack Havoc makes his appearance, and at this point the film falters badly. Tony Wright, who plays the part, may have been a capable actor for all I know, but he simply doesn’t project the menace we’ve been led to expect. Moreover, the fog dissipates and the visuals quiet down as the plot eventually moves off to sun-drenched Brittany and a conclusion that recalls the endings of Saboteur and North by Northwest.

There’s a surprising scene at the three-quarter mark where the heroine’s vicar father tries to reclaim Havoc’s soul, intelligently done and well-played, but it somehow misses the pathos and emotion it should have carried.

Ah well. There is, however, one surprisingly effective character: one Lucy Cash, a respectable, church-going and totally repellant creation who sucks blood out of the local poor people, and she’s played with quiet assurance by Beatrice Varley, whom you may remember from Horrors of the Black Museum. At any rate, she leads us to a minor plot twist where (SPOILER ALERT!) it turns out she’s Jack Havoc’s mum. Which makes his real name Johnny Cash, so you can see why he changed it.

Editorial Comment: David Vineyard reviewed both the book and the film nearly four years ago on this blog. Check out what he had to say here.

Sun 11 May 2014

Reviewed by JONATHAN LEWIS:

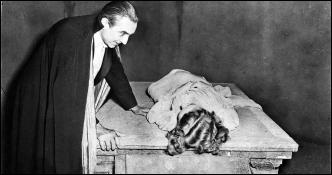

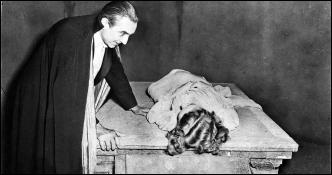

THE RETURN OF THE VAMPIRE. Columbia Pictures, 1943. Bela Lugosi, Frieda Inescort, Nina Foch, Miles Mander, Roland Varno, Matt Willis. Director Lew Landers.

The Return of the Vampire is a 1943 Columbia Pictures horror film directed by Lew Landers (The Raven) and starring Bela Lugosi (Dracula). Viewers with even a cursory knowledge of twentieth-century European history will especially appreciate the significance of the film’s historical context, while Lugosi fans will certainly enjoy the Hungarian-born actor’s portrayal of the vampire Armand Tesla, Count Dracula in all but name.

The film, which runs just under 70 minutes, benefits from good pacing, well-developed and believable characters, and the theme of free will in the face of cosmic evil. The latter is something that audiences at the time would likely have implicitly associated with the ongoing campaign against Nazism.

The plot is fairly straightforward, making the film not particularly difficult to follow. We begin in October 1918, a month shy of the end of the Great War. The vampire Tesla and his werewolf assistant, Andreas, inhabit a misty graveyard outside London. Tesla attacks and bites the neck of a young girl named Nikki, who lives in an estate not far from the vampire’s earthly domain.

Nikki’s grandfather, Professor Walter Saunders (Gilbert Emery), and Lady Jane Ainsley (Frieda Inescort), a scientist, soon realize that Nikki’s wound has a dark, supernatural origin. They’re determined to do something about it. Together, they enter the graveyard, find Tesla’s tomb, and drive a stake through the vampire’s heart. This entire sequence is best be interpreted as an allegory of the conclusion to the violent and culturally disruptive First World War.

Unfortunately, peace with Tesla, much like Britain’s peace with Germany, was not built to last. The film shifts forward in time to the Second World War. Lady Jane’s son, John, is engaged to Nikki (Nina Foch) and Andreas (Matt Willis), no longer a werewolf, is working in her laboratory.

But Britain is at war and the Luftwaffe’s bombing raids are taking their toll on London. One such aerial raid directly hits the cemetery and ends up freeing the monstrous Tesla from his coffin. Apparently, the stake through the heart didn’t take.

Tesla transforms Andreas back into a werewolf. He seeks revenge against Lady Jane and sets out to transform Nikki into a vampire. Lady Jane is once again tasked with the unenviable job of battling Tesla who, for a time, passes himself off as Hugo Bruckner, German scientist eager to defect to the United Kingdom. She has the cooperation, if not the full assistance of Scotland Yard investigator, Sir Frederick Fleet (Miles Mander), who simply doesn’t believe in vampires.

Although the film is nominally about Tesla, the character of Andreas plays a prominent role as well. One can interpret his story as either an allegory of the perils of addiction or as previously alluded to, of free will in the face of evil.

The viewer first encounters Andreas as a werewolf, lumbering through a spooky graveyard, completely beholden to his master, Tesla. Andreas’s first on-screen transformation occurs when Professor Saunders drives a stake through Tesla’s heart, freeing him from the vampire’s control and transforming him back into his natural, human form.

Later, Tesla transforms Andreas back into a werewolf. Finally, at the end of the film, Andreas plays the hero and is transformed back into a man. Each transformation represents a turning point in the film’s narrative structure.

In conclusion, The Return of the Vampire is as much a horror film as an allegory about Britain’s two conflicts with Germany. Although the film isn’t a classic, the acting is decent and there is a worthwhile message involved. Most importantly, however, is the fact that it’s actually quite fun, the type of movie one can enjoy on the couch, late at night, lights off and popcorn in hand.

« Previous Page — Next Page »