May 2016

Monthly Archive

Sat 7 May 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

Reviewed by DAN STUMPF:

P. G. WODEHOUSE – Jill the Reckless. Herbert Jenkins, UK, hardcover, 1921. George H. Doran, US, hardcover, 1920. Serialised in Collier’s, US, 10 April to 28 August 1920, as “The Little Warrior,” and in Grand Magazine, UK, September 1920 to June 1921. Reprinted many times.

A sizzling, searing look at the sleazy underside of Broadway and the downtrodden dreamers who dance desperately to the sordid melody of despair.

Well, maybe not quite, but it is a bit different from Wodehouse’s usual thing. We get the customary mismatched engagement, disapproving dowager, silly-ass aristocrat and captivating young things in love, but Wodehouse serves it up with a bit of a change here.

For one thing, the central character in this book is female — a rarity in Plum’s male-centered universe — a well-to-do young lady, Jill Mariner, of a rather impulsive disposition (hence the title of the piece) engaged to tall, handsome and politically rising Derek Underhill, whose domineering mother looks on the planned nuptials with something less than enthusiasm, particularly when Jill is seen chatting with a friend from her childhood, now grown into a bemusing playwright.

With a nod to classical Greek tragedy, Wodehouse engineers a day for Jill that includes being arrested (for assaulting a man who was beating a parrot) getting jilted by Derek, and discovering that her guardian, lovable old Uncle Chris, has spent her trust fund and she is now penniless.

Well, characters in Wodehouse novels are almost always short of cash, but they are never actually destitute and desperate as Jill is here, and in short order, Uncle Chris takes her to upstate New York and berths her with some distant and miserly relations who soon begin treating her like a servant.

Wodehouse, however, is no David Goodis, Jill Mariner is no Jane Eyre, and we soon find her in Manhattan, employed as a chorus girl for a Broadway show-in-the-making, and being romantically pursued by the author of the show, the producer, and her bemused playwright friend who has been hired to re-write and fix it.

But wait, there’s more: Back in London, word has got out that Derek (remember him?) jilted Jill because she went broke; bad show, that, in everyone’s opinion, and when their mutual friend Freddie (the silly-ass of the piece) tries to explain that the break-up arose from a man beating a parrot… well Wodehouse fans know what sort of scenes will ensue, and Freddie is dispatched to America to find Jill and bring her back, only to have his mission run off the tacks when he inadvertently becomes a Broadway star.

You have guessed by now that Wodehouse’s view of struggling in the Big City is never terribly grim; when Plum writes about poverty, he treats it with the same sly humor (or humour, as he would have called it) he applied to his own deprivation in a Nazi internment camp: Keep calm and dither on.

There is also a bit more emotional complexity here than usual. Characters in Wodehouse stories get engaged, disengaged and re-engaged with the metronomic ease of a well-oiled clockwork toy, but here there’s heartbreak to endure and be gotten over. There’s a very telling scene where Jill explains to one of her suitors that her heart is like a room full of old ugly furniture and she won’t have room for anything new there until she can get rid of the old stuff. It’s an apt metaphor, unusually melancholy for Wodehouse, and perfectly sweet.

Fear not, though; this is still a Wodehouse novel, filled with its full quota of laughable situations and colorful characters who seem as briefly real and amusing as usual. Jill the Reckless may surprise Plum’s fans, but it won’t disappoint them.

Sat 7 May 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

ANTHONY BERKELEY – Dead Mrs. Stratton. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1933. First published in the UK as Jumping Jenny, hardcover, 1933. Reprinted by The Hogarth Press, UK, softcover, 1984.

In 1933 mystery writers were still playing around with the conventions of the puzzle aspect of the detective story, with authors having lots of fun playing games with the reader, pulling the wool over their eyes, and otherwise very much playing magician in a literary format. Dead Mrs. Stratton, the US title, is solidly in that tradition.

Which makes it difficult for a reviewer (not a critic) to talk about a book such as this one, for fear of saying too much, giving too much away that the reader would far rather find out for his or her own. My way of compensating for this is by warning you that from this point on nothing I say will be exactly true. Or it may be true, but I won’t tell you whether it is or not. On the other hand, everything may be true.

The protagonist of this tale is noted amateur criminologist Roger Sheringham, in the ninth of ten appearances. Dead is a woman whose mad and outrageous behavior is uniformly despised by all. Her husband, a mild-mannered man who may have loved her once but no longer and is said to love another, but he dare not bring up the subject of divorce, for fear of her reaction and perhaps other secrets about their friends and family that she may reveal.

At a party hosted by her husband’s brother she also threatens suicide, and it is no surprise for the assembled guests to discover toward the end of the evening that she has done precisely that. Roger, a good friend of the host, is suspicious, and realizing that it was murder and the husband is the most obvious suspect, finds himself manipulating the evidence to insure the coroner’s verdict is that of suicide.

Here is where the author steps in and makes sure we know more than Sheringham does, so it becomes extremely amusing to watch the latter eliminate the real killer and discover that he has inadvertently made himself the obvious suspect instead, should the police be intelligent enough to look beyond surface appearances. Which, as it turns out, they are, and they do.

There is much heavy huddling around by Sheringham with the other guests at the party to get their stories to gibe with his, and much smile-provoking consternation on his part as well, when they don’t. This means that there isn’t a lot of action in this novel — practically none — but the plotting is extremely intricate and detailed. This is not a book that is designed for modern day readers, but outdated or not, I found that doing my best to stay abreast of Sheringham’s trials and tribulations was a very enjoyable task, and the ending was just a huge, huge bonus. (At is turns out, Sheringham never does know who the killer is.)

Fri 6 May 2016

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Crider:

G. G. FICKLING – This Girl for Hire. Pyramid G274, paperback original, 1957. Reprinted at least four times by Pyramid. Cover art by Harry Schaare.

G. G. Fickling was the pseudonym of the writing team of Forrest E. (“Skip”) Fickling and his wife, Gloria, creators of Honey West, billed on the front cover, the back cover, and even the spine of This Girl for Hire as “the sexiest private eye ever to pull a trigger!” Honey’s sex is made much of in the course of the book: She spends as much time getting into and out of bathing suits as she does working on the case,and her measurements (38-22-36) are cited both on the back cover and in the text.

The case itself, which involves eight deaths before it ends, begins when Honey is hired by a down-and-out actor whose apparent murder leads to the other killings, all of people involved in the television industry. Despite the setting, there is little actual insight into television, unless the actors, producers, and directors really do spend most of their days and nights drinking and carousing.

The book is filled with incident, even including a strip-poker game, but the plot is so confusing that the reader is unlikely to be convinced by its unraveling, which comes about more by accident than by good detective work. Still, there is a certain pre-feminist charm in seeing the hard-boiled Honey at work in a man’s world, despite Lieutenant Mark Storm (his real name) and his attempts to persuade her to leave the brain work to the men.

Pyramid Books occasionally referred to Honey West as “literary history’s first lady private eye,” and undoubtedly the novelty of a female first-person narrator helped sell the series, but James L. Rubel’s Eli Donavan was playing the same part years earlier in Gold Medal’s No Business for a Lady (1950). Still, it was Honey who wasa success, starring in eleven books and a TV series in which she was portrayed by Anne Francis.

The Ficklings produced one other short-lived series for Belmont Books, this one featuring a male private eye named Erik March, in such titles as The Case of the Radioactive Redhead (1963).

—

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Fri 6 May 2016

REVIEWED BY JONATHAN LEWIS:

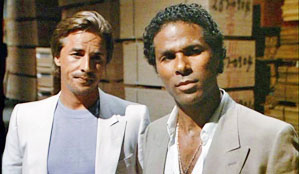

MIAMI VICE. “Heart of Darkness.” NBC, 28 September 1984. (Season 1, Episode 2.) Don Johnson, Philip Michael Thomas, Saundra Santiago, Michael Talbott, John Diehl, Olivia Brown, Gregory Sierra. Guest Cast: Ed O’Neill, Paul Hecht. Created by Andres Carranza & Anthony Yerkovich. Executive producer: Michael Mann. Directed by John Llewellyn Moxey.

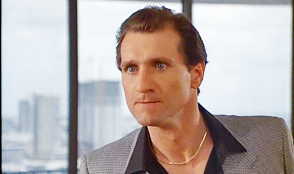

Before he portrayed the crudely affable father on Married with Children, Ed O’Neill guest-starred on this rather neo-noir Miami Vice episode. Entitled “Heart of Darkness,†this first season episode is, unlike many extremely dated 1980s cop shows, still eminently watchable today. Stylishly photographed, the episode feels less like a television show and more like a gritty crime film.

O’Neill portrays Arthur Lawson, an undercover FBI agent tasked with investigating an illicit pornography ring and its concurrent corruption. Problem is: under the alias Artie Rollins, Lawson may be having too much fun with his assignment. So much so that the feds believe that Lawson may have changed sides.

“Heart of Darkness,†the second regular Miami Vice episode to be aired on NBC, served to demonstrate to audiences that the series was not going to be just another police procedural. Undercover work wasn’t all fun and games and sometimes the dividing line between cop and criminal would become blurred. The episode was an opportunity to draw out the personalities of the two main lead characters: Detective James Crockett (Don Johnson) and Detective Ricardo Tubbs (Philip Michael Thomas). While Tubbs is quick to assume that Lawson has gone over to the proverbial dark side, Crockett isn’t so sure. A veteran of numerous undercover operations, Crockett sees himself in Rollins and wants to give the G-Man the benefit of the doubt.

Much as in some neo-noir films, the city itself is a character in the unfolding drama. Nightclubs, restaurants, warehouses, boulevards, and luxury condos are the settings that Miami Vice would turn to time and again.

The final shootout, which takes place at the port, reminded me of a similarly filmed scene in Richard Donner’s Lethal Weapon 2 (1989). There’s little romanticism on display here. The world in which Crockett and Tubbs operate is very much a kill-or-be-killed one. The same goes for Arthur Lawson who comes across less as a villain and more as a tragic figure caught between the normal world of middle class domesticity and the seedy underbelly of 1980s urban life.

Thu 5 May 2016

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Anyone remember a Cornell Woolrich story called “The Fatal Footlights� It first appeared in Detective Fiction Weekly for June 14, 1941 and finally found a hardcover home when I included it in my Woolrich collection NIGHT & FEAR (2004). The setting is a cheap burlesque house on New York’s 42nd Street and the plot kicks off when the featured dancer, who performs with her body painted gold all over, collapses on the runway during a show and dies.

We soon learn that it was the gold paint that killed her, and that someone had stolen the paint remover from her dressing room precisely in order to cause her death without laying a finger on her. Of course, what death by gilding conjures up for most of us is not this obscure Woolrich story but the James Bond movie GOLDFINGER (1964) and Ian Fleming’s 1959 novel of the same name. Fred Dannay had reprinted Woolrich’s story in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine for June 1955 under the new title “Death at the Burlesque,†and if the tale came to Fleming’s attention it was probably by this route.

For the media the megadeath of April 2016 was that of pop icon Prince. But just one day earlier, on the 20th of the month, death claimed the director of GOLDFINGER — and of several other Bond films. Guy Hamilton was born in Paris of English parents in 1922 and entered the British film industry after service in World War II. In 1952, having put in a few years as an assistant director, he made his first film, THE RINGER, based on something — whether a novel, a story, a play or just the character is unclear — by Edgar Wallace.

It wasn’t until his involvement with Sean Connery and GOLDFINGER that he came to prominence, and in later years he directed three other Bond films: DIAMONDS ARE FOREVER (1971), again with Connery, and LIVE AND LET DIE (1973) and THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN (1974), both starring Roger Moore. He also contributed to the more serious type of espionage film as director of FUNERAL IN BERLIN (1966), based on the novel by Len Deighton and starring Michael Caine.

Near the end of his career he helmed two pictures based on Agatha Christie novels and filmed in the manner of MURDER ON THE ORIENT EXPRESS, with a huge budget and tons of guest stars. THE MIRROR CRACK’D (1980) starred Angela Lansbury as Miss Marple, with guest stars including Tony Curtis, Rock Hudson, Kim Novak and Elizabeth Taylor, while Peter Ustinov took the lead as Hercule Poirot in EVIL UNDER THE SUN (1982), with Maggie Smith, Roddy McDowall, James Mason and Diana Rigg among the guest stars.

The actress in GOLDFINGER who met her death by gilding was Shirley Eaton (1937- ). As chance would have it, I met Ms. Eaton twenty-odd years ago, at the Memphis Film Festival. We both happened to pick the same time to have lunch in the convention hotel restaurant and out of the blue she asked if she could sit with me, saying she didn’t like eating alone.

Was I a hot dude in those days or what? No, I didn’t make a pass at her, nor she at me, but in her middle fifties she was still quite lovely. I was interested in Guy Hamilton, GOLDFINGER’s director, and asked if she knew how I could get in touch with him. She told me that she understood he’d retired and moved to Majorca. With no more to go on than that, I wasn’t able to track him down. Now he’s gone for good. Obituaries indicate that Majorca was indeed his final home.

So why was I interested in Hamilton? Not because of GOLDFINGER, or any other Bond film, and not because of the Christie-based pictures either. Just before GOLDFINGER, Hamilton had directed a picture that fascinated me: a commercial failure, not even mentioned in the New York Times obituary, but one that I was using in my Law and Film seminar at St. Louis University and wanted to write about. Odds are that no reader of this column has seen or heard of it.

The literary source of the film was the 1959 novel THE WINSTON AFFAIR by Howard Fast (1914-2003), a super-prolific author who was a Communist and, back in the Red Menace era, served a prison term for contempt of Congress. Among general readers he’s best known as the author of SPARTACUS (1951), source of the blockbuster movie with Kirk Douglas; among mystery fans he’s remembered for the whodunits he wrote as E.V. Cunningham.

No one would call THE WINSTON AFFAIR a mystery but it might be considered a legal thriller. The time is late in World War II and the place is India, which Fast knew well from his work as a war correspondent. Large numbers of British and American troops are serving in the area side by side and tension between the two armies is running high.

Barney Adams, a West Point graduate and wounded combat veteran, is assigned as defense counsel at a court martial. The defendant, Lieutenant Charles Winston, is a middle-aged misfit who at a military outpost in the boondocks cold-bloodedly shot to death a British sergeant in full view of several witnesses.

In order to restore unity with their British allies, the American commanders are determined that Winston be tried promptly and hanged. But since Winston happens to have a Congressman as his brother-in-law, the court-martial must be conducted not in the drumhead style but with the facade of due process preserved. It’s made clear to Adams, however, that he is not to raise the only defense available: insanity.

Everyone with professional expertise admits privately to Adams that Winston was and still is insane but a “lunacy board†with no psychiatric experience has ruled to the contrary. At a press conference before the trial, Adams responds to an Indian journalist’s question with the statement that might does not make right and justice can only exist apart from power. Once the court-martial begins, he jumps the reservation and goes all out to establish an insanity defense, clearly destroying his own military career in the process.

The biggest problem with THE WINSTON AFFAIR is that, like so much “socially conscious†fiction, it’s heavy on earnest rhetoric and light on drama. In MAN IN THE MIDDLE (1963), the movie based on Fast’s novel, the Debate on Great Issues tone is either scrapped or, where kept, is made subordinate to story and character.

Let’s compare the first few paragraphs of WINSTON and the first minute or so of the movie. Fast begins with a banal exchange of dialogue between the area’s commanding general and his sergeant. Guy Hamilton opens the movie with a stunning pre-credits sequence as we watch Winston (Keenan Wynn) stride from his quarters to the tent barracks, walk into the British sergeant’s canvas cubicle, take out a pistol and pump four bullets into him. In the novel we never see the murder.

Barney Adams is the protagonist of both works but his biography differs sharply from one to the other. Fast’s character is a captain, 28 years old, six years out of West Point and an honors graduate of Harvard Law School. The Adams of the movie looks to be in his mid-forties, as Robert Mitchum was when he played the role, and accordingly holds the higher rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

This version of the character knows next to nothing about military law and certainly never went to a civilian law school. He’s invested much more of himself in his career as a soldier than has Fast’s Adams, and if he sacrifices that career trying to save his pathetic and disgusting client, the stakes are much higher than they are for his novelistic counterpart.

The ultimate evil in Fast’s novel is anti-Semitism. Winston is a paranoiac who believes he’s being plotted against by “international Jewry, the Elders of Zion, the whole kit and kaboodle of Nazi filth.†A Jewish officer calls him “a decaying cesspool of every vile chauvinism and hatred ever invented…, who spat in my face and called me a kike and a sheeny….â€

Guy Hamilton and his collaborators drop the anti-Semitism theme, a decision which displeased Fast mightily, and anachronistically replace it with what in the early 1960s was much more timely. You guessed it. Racism. The British sergeant he killed, Wynn tells Mitchum, “was altogether an evil man. He’d sit and spout democracy, then he’d go out….Up into the hills, one of these native villages. He had women up there. Black women. I saw him!….I used to follow him up that hill and watch him with those black witches up there. He was defiling the race, Colonel….He wasn’t fit to live in a white man’s world.â€

As Mitchum is leaving the guardhouse, Wynn is taken out for his daily exercise. Guy Hamilton places us with Mitchum, looking down into the sunken prison yard, watching Wynn pace back and forth in an enclosed stone cube that is a perfect visual correlative for his racism.

I could go on for many more pages — and did just that in a chapter on the movie and Fast’s novel that was first published in the University of San Francisco Law Review and is included in my Edgar-nominated JUDGES AND JUSTICE AND LAWYERS AND LAW (2014) — but space compels me to cut to the bottom line.

The key to understanding the differences between novel and film is that, during the four years between them, two monumental events occurred: the publication of Harper Lee’s TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD (1960) and the release of the classic film version (1962) with Gregory Peck. Hamilton’s movie does what Fast’s novel couldn’t have done.

Robert Mitchum’s version of Barney Adams creates a new type of Atticus Finch figure: tough and laconic, almost a Philip Marlowe in khaki, where Atticus was loving and compassionate; representing not a sympathetic and clearly innocent black man in the South of the 1930s but a guilty white racist of the worst sort. “It’s easy to fight for the innocent,†Mitchum says, perhaps referring subtly to Atticus. “But when you fight for the sick, for the warped, for the lost, then you’ve got justice.â€

His (and Guy Hamilton’s) Barney Adams doesn’t have a license to practice law but, as I see it, offers a more challenging and less reassuring incarnation of the lawyerly ethos that is permanently linked in the public mind with the years of the Supreme Court under Earl Warren.

We’ve come a long way from Cornell Woolrich and death by gilding and it would be hard to end this column neatly by going back. Since many readers of this column are movie buffs, I’ll close by quoting a letter about MAN IN THE MIDDLE sent to me by Howard Fast early in 1996.

Most of the shooting, he said, took place “on Lord Somethingorother’s estate about ten miles out of London. I was in London with my family and I watched a good bit of the filming. Bob Mitchum was wonderful. For me he was the best film actor of his time. Each day he sat quietly on the set, putting away a quart of whisky. When his scene came he never flubbed a word, while the British actors were flubbing all over the place. They never had to do a second take because of Mitchum… I was awed by the ability of the British film makers to reproduce an Indian setting there near London.â€

Wed 4 May 2016

Reviewed by DAN STUMPF:

CRY DANGER. RKO, 1951. Dick Powell, Rhonda Fleming, Richard Erdman, William Conrad, Regis Toomey, Jean Porter and Jay Adler. Written by William Bowers and Jerome Cady. Directed by Robert Parrish.

A tight, fast-moving and witty noir, done by folks who knew how to do it.

Dick Powell stars as Rocky Mulloy, just released after five years in prison for an armed robbery he didn’t do, freed when his alibi is belatedly substantiated by the rather suspect testimony of ex-Marine Delong (Erdman.) Actually, Delong thinks he’s guilty, but he’s angling to cut himself in for a share of the $100,000 still missing from the robbery.

Also involved, in ascending order of importance, are Regis Toomey as Cobb, a dull cop who still thinks Rocky’s guilty but figures he can shake things up by tailing him around town; Castro (William Conrad) the Gang Boss who engineered the heist but kept his hands clean, and Rhonda Fleming as Nancy, an ex-love of Rocky’s now married to his buddy Danny, who is still serving time for the caper.

Now that he’s out, Rocky hopes to clear his own name and that of his friend Danny, and maybe even get a cut of the loot to repay himself for the five years in stir. To this end, he and his new friend Delong move into a trailer court — a wonderful blend of location and studio work that seems really tacky in the way only a 1950s trailer court could — as a base for their operations while Rocky begins following up the loose ends left dangling for five years: the widow of the Security Guard who identified him, Castro’s involvement, and just how innocent his old buddy Danny really was.

By this time in his career, Powell had mastered the cool, hard-boiled, faintly mocking persona that had been his stock-in-Spade since Murder My Sweet (1944) and Writer Bowers (Criss-Cross, The Web, The Law and Jake Wade, etc.) gives him plenty of laconic dialogue to deal out, which he does with perfect deadpan comic timing.

There’s some debate over whether this was directed by Parrish or Powell — both have some fine films to their credit — but whoever did it captured a nice feel for that post-war early 1950s ambiance, evoking atmosphere without letting the pace flag for a minute. Additionally, Cry Danger achieves a moment of some depth and emotional complexity, which I’ll preface with a

SPOILER ALERT! It will come as small surprise to noir buffs that Nancy turns out to be playing a double game, hoping to keep the loot and get Rocky back into her larcenous arms, but we get a nifty spin on it here when Rocky uses her love for him to get her to betray herself. All through the scene we can see him leading her on and hating himself for it, see him crushing his feelings under his own heel, and finally walking away, officially innocent, free and very alone. A fine and unusual moment, written and played to perfection. END OF SPOILER ALERT.

Along the way to this remarkable ending we get a full quota of twists, turns, rough stuff and the kind of tough guys and deadly dames they just don’t make anymore — if they ever did.

Wed 4 May 2016

Reviewed by DAVID VINEYARD:

TWENTY PLUS TWO. Allied Artists, 1961. David Janssen, Jeanne Crain, Dina Merrill, Brad Dexter, Jacques Aubachon, Robert Strauss, Agnes Moorehead, William Demarest. Screenplay by Frank Gruber, based on his novel. Directed by Joseph M. Newman.

Julia Joliet, who runs a clipping service in Hollywood whose chief client is movie star Leroy Dane (Brad Dexter), is brutally murdered and her offices searched. It seems like a pointless crime, but among her clippings is one on Doris Delaney, a debutante who went missing over a decade earlier from her exclusive school and wealthy home in New York, and that catches the eye of Tom Alder (David Janssen) who makes his living finding missing people, and for whom the Delaney case is a sort of obsession.

When Alder casually arranges to run into Dane at a bar he also coincidentally is spotted by Linda Foster (Jeanne Crain), the girl who sent him a Dear John letter while he was in the service in Tokyo recovering from a wound that has healed better than his heart. Linda is there with her latest fiancé, but not averse to reopening the relationship with Tom, and also accompanied by her friend Nikki Kovacs (Dina Merrill) and her wealthy fiancé.

When Alder finds a clue that was meaningless to the police in Joliet’s place it puts him on a plane to New York, surprisingly along with Nikki Kovacs who is getting off in Chicago to see family. There is something about her Alder can’t quiet shake, but he hasn’t time to pursue it. He is also, unknown to him, being followed by a mysterious cultured fat man who he saw outside Joliet’s apartment.

In New York he begins to piece together the pieces of the Delaney case with the help of a drunken reporter (William Demarest), a private eye buddy (Robert Strauss), and Mrs. Delaney (Agnes Moorehead) who suspects he is nothing but another opportunist until he makes the first real break in the case in over a decade. Meanwhile things are moving along on other fronts.

The mysterious fat man is Jacques “Big Frenchy†Pleschette (Jacques Aubachon), a former con man who has spent most of his adult life in prison, and who is willing to pay $10,000 to find his estranged younger brother Auguste who he has not seen since the war. Linda Foster has shown up too, concerned about Nikki Kovacs, who has gone missing and it turns out has no family in Chicago, and also looking to renew romantic relations with Alder. Even Leroy Dane shows up on a publicity tour.

With the pressure on Alder recalls in flashback a girl he met in Tokyo, Lily Brown, while he was recovering from his wound, and fell for.

And as he pieces together all the diverse bits of information he gathers in his investigation it all begins to dovetail together in dangerous ways.

I won’t go any farther, you probably have figured it out anyway. Despite the noirish elements Twenty Plus Two is really just a pretty good little mystery and not film noir. Alder is only mildly haunted and obsessed, and everything falls together a bit too neatly. The film plays mostly as a made for television movie and not a feature, a fact enhanced by the kind of guest stars and cast you would expect on television in the period.

That said, this film, produced by Frank Gruber, from his own novel and screenplay, is still pretty good in a low key way, and notable in that much of the sub plot is borrowed from Eric Ambler’s A Coffin for Dimitrios, which became a film, Mask for Dimitrios, with a screenplay by Frank Gruber. Big Frenchy Pleschette is Mr. Peters, the character played by Sidney Greenstreet in the film, and his brother Auguste the Dimitrios figure he wants to find — and blackmail.

Many of the plot elements were updated and moved from Hollywood and New York to Hong Kong, for The Gold Gap (reviewed here ) another Gruber novel from late in his career, and the missing heir who has changed their life also appears as a key element in Gruber’s Bridge of Sand.

Pulp writers never let anything go unused.

Twenty Plus Two was a better book than film; it plays too much like a two-part episode of a television anthology series to ever really gel as a feature, and noirish elements don’t make noir, but it is professionally done all around, attractive, well written, cogent, and all the elements do tie together neatly even explaining why Julia Joliet had to be killed.

There is nothing exciting about it, but it is a satisfying little mystery film that crosses and dots all the right letters, thanks to Gruber’s expertise in the field, even if the long arm of coincidence in this one at times seems to belong to Plastic Man.

Tue 3 May 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

THOMAS B. DEWEY – Don’t Cry for Long. Simon & Schuster, hardcover, 1964. Pocket, paperback; 1st printing, March 1966.

I posted a review here last October of one of Dewey’s Pete Schofield books, and it was not a very positive one, I’m sorry to say. The good news is that Don’t Cry for Me, the 10th of 17 books in his Chicago-based PI “Mac” series, is as far on the plus side as Nude in Nevada was on the minus side.

There’s no long buildup to the case that Mac is by default given to handle. The murder of a young girl’s bodyguard occurs on page 9 (in reality the third page of the story) and all of the ensuing action takes place in no more than two or three day’s time.

The girl’s father is a Congressman, which means he and therefore his daughter has many enemies. but Mac suspects that the killing is more personal than that.

Along the way Mac meets a woman, the girl’s no-nonsense chaperon who does not flinch an inch in her duties along those lines, and who may become the woman in Mac’s life. One of the threads of concern to the reader is whether or not she will still be that woman by the time the book ends.

Dewey’s prose in this book is terse and hard-boiled, more like Hammett than Chandler, in my opinion, but as a person Mac cares more, and in so doing resembles some of the characters in Chandler’s books more than he does any of the leading characters in Hammett’s. The fact that I’m doing any such comparisons with either author means that really enjoyed this one. If PI fiction is a substantial portion of your usual reading fare, I think you may, too.

Tue 3 May 2016

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marvin Lachman:

ROBERT L. FISH – The Green Hell Treasure. Putnam’s, hardcover, 1971. Hardcover reprint: Detective Book Club, 3-in-1 edition. No paperback edition found.

Though the Edgar-winning Fugitive (1962) was the first of ten mystery novels Robert Fish wrote about Jose Da Silva, The Green Hell Treasure is far more typical of the series. Because The Fugitive is about an escaped Nazi war criminal in South America, it is, of necessity, more serious than its successors.

As his series progressed, Fish would make increased use of Brazil, where Da Silva, a police captain, acts as liaison between the Brazilian police and Interpol. The subject matter of his books became more exotic, and humor played a greater role.

Robert L. Fish knew Brazil intimately, having spent more than ten years there as a consulting engineer with a Brazilian vinyl plastics firm. Fish always preferred to use places in which he had lived or traveled as background for his work. Brazil, a combination of virtually impenetrable jungle and modern cities and resorts, is ideal for a man like Da Silva who is at home in any of these settings.

Early books such as Isle of the Snakes (1963) and The Shrunken Head (1963) emphasize the primitive, especially the exotic and dangerous fauna and Indian headshrinkers. Though on the surface detective stories, they are as much thrillers. By the time of The Green Hell Treasure, the series had become a satisfying blend of sophistication and adventure.

Throughout the series, Wilson, an undercover agent at the American Embassy in Rio de Janeiro, plays “Watson”to Da Silva. If their byplay is not quite in the Wolfe-Goodwin class, it is still very witty indeed. In The Green Hell Treasure, they start out in Brazil, as usual, but then travel to Barbados in pursuit of half a million dollars in stolen jewels, the titular treasure.

In an extremely amusing scene, the intrepid Da Silva is transformed into a nervous wreck due to his fear of flying. If the solution is somewhat obvious, the book is resolved in an exciting climax told in almost cinematic language. This is not surprising when one remembers that Fish, under his Robert Pike pseudonym, wrote Mute Witness (1963), which wasadapted to the screen as the very exciting Steve McQueen film Bullitt (1968).

Nor should the humor in The Green Hell Treasure amaze us when one thinks of Fish as the author of The Incredible Schlock Homes and, under another ichthyological pen name. A. C. Lamprey, an amusing series of comic definitions in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine called “Gumshoe Glossary.”

Fish’s other books under his own name are equally diverse. The novels The Hochmann Miniatures (1967), Whirligig (1970), The Tricks of the Trade (1972), and The Wager (1974), and the short-story collection Kek Huuygens, Smuggler (1976).

—

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 2 May 2016

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

KARL KRAMER – Fair Game. Popular Library #650, paperback original; 1st printing, March 1955.

Karl Kramer was the pen name of Edward A. Morris, (1912?-1996?), about whom little more seems to be known, not even the exact dates of his birth and death. He had one story published in the December 1958 issue of Manhunt, “Wait for Death,” and four paperback crime novels published by Monarch Books between 1959 and 1961.

If Gold Medal was the pinnacle of hard-boiled paperback crime novels in the 1950s, and Monarch was way down on the bottom rung of the latter, that leaves Popular Library as (obviously) somewhere in between. The covers were generally very racy, but whether the stories matched up, I’d say it was doubtful, save for one scene in each and every book that the cover artist was always able to take full advantage of.

On the average I would say that the Popular Library offerings along these lines was higher than those of Ace and the Ace Double line, but that was before I read Fair Game, which no matter what scale you might care to use, most definitely brings that average down.

It starts slow, stays slow for a long time, then ends in a blaze of action that left me slightly bewildered as to who was on what side and why. It didn’t matter all that much: only one of the characters is mildly interesting.

The story is told by Steve Conney, a pilot-for-hire who works exclusively for glamorous magazine publisher Helen Abbott, who uses his services not only in the air but in the bedroom — when it serves her needs. Their present assignment: to track down a mysterious Dr. York. Conney does not know why, nor does Helen deign to tell him — but for the first time, she has brought a gun along with her.

The trail has led them to an isolated resort on lake two-and-a-half hours out of New York City. The place is owned by an old man but managed by his beautiful blonde and widowed daughter-in-law, Eve. Conney’s job as directed by Helen: to get close to her and pump her for information. And eventually that he does — get close to her, I mean, and Helen does not react well.

More: nothing is what it seems, and Conney is the kind of lunkhead who thinks he knows women but in reality doesn’t have a clue. He might be portrayed well by Charlton Heston. Helen, perhaps someone like Ida Lupino — icy when she wants to be and passionate at other times. The initially cold and aloof Eve, why not Grace Kelly, as long as my make-believe budget can handle it.

I hope I didn’t make this story more interesting than it is. It isn’t. It’s slow and tedious, but the author, whoever he was, had a passion for flying that carries over to the reader for a brief couple of pages; this partially outweighs all of the story’s other shortcomings.

« Previous Page — Next Page »