October 2018

Monthly Archive

Wed 10 Oct 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[8] Comments

LAWRENCE BLOCK – Time to Murder and Create. Matt Scudder #2. Dell, paperback original, 1977. Avon, paperback, 1991. Dark Harvest, hardcover, 1993.

This book was published relatively early in Block’s career, hence the fact that when it first came out, it was as a lowly paperback original. The first hardcover edition didn’t come along until many years later, well after later books in the series had started to gather quite a lot of critical attention and acclaim.

Many people like to go through a series in order, and because there has been some question about that, it was Block himself who has verified that Time to Murder and Create was the second to be written but the third to be published. Having that additional insight into the growth of a fictional character is a big plus to many fans, and Matt Scudder has become a guy who has lots of them.

But just in case he’s someone who’s new to you, Scudder is an ex-cop who quit the force soon after accidentally killing a small child by a ricocheting bullet in the line of duty. He manages a small living acting as an unlicensed private investigator.

In this book he’s approached by an acquaintance generally known as Spinner. Spinner is not really a friend, but recently he seems to be doing well, as if he has come into some money.

He has a favor to ask of Scudder, who after agreeing is given an envelope to be opened on the occasion of Spinner’s death.

Not surprisingly, that’s exactly what happens. When Spinner’s body is pulled from the East River, Scudder opens the envelope and … you may be ahead of me. If you’ve already guessed that Spinner had been doing some blackmailing, you’d be right.

He’d had his hooks into three people, as a matter of fact, and in all likelihood, one of them is responsible for his death. Scudder decides that it’s up to him to find out which one it is.

It’s easy to tell that Block is the author of both the Scudder books and his “Burglar†series — the voice is exactly the same — but even as early in the series as this one is, it has a harder edge to it than any of the Bernie Rhodenbarr ever had.

As always, or so it’s been my experience, the mystery itself may not be your primary reason for reading a book by Block. It’s the voice, the rhythm, the attitude, the take you out of your everyday problems, even if only for a short time. Two or three hours will do for me.

Any of his books, including this one.

Tue 9 Oct 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[10] Comments

JOHN CREASEY – Model for the Toff. Richard Rollinson (The Toff) #36. Pyramid R-1134, paperback; 1st US printing, February 1965. Originally published in the UK by Hodder & Stoughton, hardcover, 1957.

The first third of this 1950s Toff thriller is quite readable, but even then I was wondering if there was enough to the story to fill an entire book. It turned out that I was right. There wasn’t.

Richard Rollinson, that upper class gent who dabbles in crime solving much as a dashing adventurer would, is hired by a famous dress designer who has been plagued by models quitting on him and others refusing to work for him. Someone is obviously trying to frighten them away, and succeeding. The question is, who? And why?

The person responsible is vicious. Some of the models have had acid thrown on them. Others have been attacked by dogs. Even the Toff’s life is in danger, once he has taken the job. There are only a limited number of suspects, however, and any suspense that the story may have is mitigated severely by the fact that the stakes are so low.

I’ve enjoyed other books in the series, but this one, not so much.

Sun 7 Oct 2018

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

DENNIS LEHANE – A Drink Before the War. Patrick Kenzie & Angie Gennaro #1. Harcourt & Brace, hardcover, 1994. HarperTorch, paperback, July 1996. Reprinted several times since.

This is a first novel. Lehane was born and raised in Dorchester, Massachusetts, and still lives in the Boston area. He has worked as a teacher of writing and a counselor of abused children, and that’s all we know about him.

Patrick Kenzie and Angie Gennaro are private detectives who are natives of Boston’s blue-collar Dorchester section, and still live there. The case that will change their lives starts simply enough: according to a prominent local politician, a black cleaning woman has stolen some important Statehouse documents from his office. He wants her found, and he wants them back.

Finding the woman isn’t that difficult; that’s their profession. Finding the “documents” and staying alive are two other stories entirely. The crime leads to other crimes, everybody’s a victim, and Boston’s ghettos threaten to erupt into an apocalyptic gang war — with our intrepid stalkers in the middle of it.

Well, hell. I thought I has my choice for Best First Novel of 1994 locked in months ago, with Mallory’s Oracle. Now along comes Lehane with A Drink Before the War, and all of a sudden the short list has grown by one, and I have to at least think about re-opening the polls.

This is a powerful story and a superbly written one. It doesn’t break any new ground in the private detective patch, and the plot is a little more cowboy than I usually like, but my goodness it’s well done.

Lehane does everything well, but what he does best are characters and prose. Kenzie and Gennaro are beautifully crafted protagonists. They have depth, and they come alive on the page. The book’s other characters are equally well crafted, though in less depth, with not a false note struck among them.

It’s all done with some of the best prose I’ve read this year. It’s not lyrical, but it’s witty, strong, and evocative. The dialogue rings true, and Lehane brings the meaner, seedier part of Boston into the living room of your mind. The book is about damaged people and a damaged society, and who does what to whom, and how, and why.

It’s bloody, and it’s hard, and I think it’ll stay with you a while. What it is more than anything else is good; astonishingly so for a first novelist, and I can’t wait for the encore, If this doesn’t win a First Novel Shamus the PWA will lose what little credibility they have with me.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #17, January 1995.

[UPDATE.] A Drink Before the War was not nominated for an Edgar, but as Barry suggested it should, it did win a Shamus from the PWA as Best First Novel for the year 1994.

The Patrick Kenzie & Angie Gennaro series —

A Drink Before the War (1994)

Darkness, Take My Hand (1996)

Sacred (1997)

Gone, Baby, Gone (1998)

Prayers For Rain (1999)

Moonlight Mile (2010)

Sun 7 Oct 2018

THE UNHOLY NIGHT. MGM, 1929. Ernest Torrence, Roland Young, Dorothy Sebastian, Natalie Moorhead (and Boris Karloff, uncredited). Director: Lionel Barrymore.

This movie, only 60 years old [and now nearly 90], has almost everything. (If it were rated today, it would get a “G”, and so it can’t have everything.) What it does have is: a fog covering all of London, a series of murders — the victims all members of a British regiment from 1915 …

… as well as a wealthy mansion, suspicious butlers, a legendary “green ghost,” a seance, a major with a scarred face, and a million pound legacy of hatred (left to the surviving members of the regiment by a former officer who was booted out). Stir and boil.

— Reprinted and very slightly revised from Movie.File.8, January 1990.

Fri 5 Oct 2018

RICHARD LUPOFF – The Comic Book Killer. Bantam, paperback; 1st printing, February 1989. Previously published in hardcover by Offspring Press, 1988. This earlier edition also contains bound-in black & white comic pages and a separate full color comic book “Gangsters at War” in a slip case. (This specially created comic book has a crucial role in the story.) Also published by Borgo Press, paperback, 2012.

I’m of two minds about this one. As the title indicates, this first real mystery that insurance adjuster Hobart Lindsey has ever had to deal with has to do with comic books, and comic book collecting in particular.

Right up my alley! I’ve been collecting comics in one way or another since I was five — but not necessarily as “collectibles,†if you see what I mean, not hardly. This one begins when a comic book shop insured by Lindsey’s company reports the theft of $250,000 worth of comics.

Lindsey is so unknowledgeable about comic books that he thinks the thief must have needed a truck to haul them away. The proprietor of the shop quickly disabuses of that idea. Only 35 books were stolen, and all of them could have fit in a single briefcase.

Trying to make a good impression with his superiors, Lindsey decides to take an active role in the investigation. This puts him in close contact with Marvia Plum, the black (and definitely female) detective assigned to the case. An immediate attraction develops, which leads to more.

Of two minds, I said. Making this one more difficult than I expected to enjoy is that I did not find Hobart Lindsey a very engaging protagonist. In the first few chapters especially I found him both callow and not particularly likeable.

And we learn even less about Marvia Plum. An unanswered question I kept asking myself is what does she see in him. Worse, the only character I really related to is the first murder victim. There is also one huge coincidence that needs to be swallowed as well. For me, it didn’t spoil the book, but it didn’t go down all that easily either.

A mixed bag, then, but there is no doubt that author Richard Lupoff knows his comic book history, and that was a big plus. If that’s a subject matter you’re interested in, I think you’ll find as much to like in that regard as I did.

The Hobart Lindsey / Marvia Plum series —

The Comic Book Killer (1989)

The Classic Car Killer (1991)

The Bessie Blue Killer (1994)

The Sepia Siren Killer (1994)

The Cover Girl Killer (1995)

The Silver Chariot Killer (1997)

The Radio Red Killer (1997, Marvia Plum alone)

One Murder at a Time: The Casebook of Lindsey & Plum (2001; story collection)

The Emerald Cat Killer (2010)

Thu 4 Oct 2018

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

RICHARD BEN SAPIR – The Far Arena. Seaview Books, hardcover, 1978. Dell, paperback, 1979.

The body was quiet as an unborn thought in a dark universe, stopped on the bare side of life, stilled on its way to death by the cold.

Lucius Aurelius Eugenianus, Roman gladiator and soldier has just been found in a state of suspended animation in the ice beneath the Queen Victoria Sea by a North Sea Oil drill bit that tears a bit of flesh from his thigh. The Texas born geologist who found the body carries it to Dr. Semyon Petrovitch an expert in cyronics in Oslo as a curiosity, but when Petrovich finds the body still has workable veins and frozen before death everything he has worked on for years seems to be coming to fruition.

By a miracle when the body is thawed and normal temperature restored, it appears to live, though a tense several days are spent desperately trying to save the frozen specimen. It is at this point in the preceding we are introduced to our narrator, Eugenianus, who is about to wake up into a world beyond his comprehension and the worst case of jet lag in the history of the planet.

Why am I not dead? Where is my death? I know death. It is a proud and free thing in a quiet place.

Alternating at first with the third person narration of the attempt to bring this time traveler to life and the first person narration gradually introducing us to Eugenianus and his story, the thing that makes this novel work is just how compelling and interesting a character he is, a man who was both in and out of time in his own world even before reaching ours.

The man dubbed John Carter by the doctors trying to keep him a secret until he can be awakened, Petrovitch hires a nun named Sister Olav who is a linguist to interpret his ravings, but all Eugenianus sees when he does awaken is a giant hovering over him, since he is of average size of his time and almost everyone in the modern world seems a giant to him, certainly the statuesque nun.

The first half of the book when the doctors are struggling to save him and we are seeing his life unfold in his memories is fascinating enough, but the book really picks up when Eugenianus awakens and finds himself in a world as alien as another planet among people who have nothing in common with him. It’s here where Sapir manages the best of his satirical jabs at the pretenses and hypocrisy of the modern world as this simple creature from the past seeks some kind of peace in a world he neither wants nor understands.

A nice balance is kept up between the techno-scientific side of the story (which for reasons Sapir likely didn’t take into account is uncomfortably close to the resurrection of Captain America in the Silver Age of Marvel Comics) and the personal stories of the main characters, Eugenianus, the geologist, Petrovitch, and Sister Olav.

Sapir, who co-created Remo Williams, the Destroyer (co-writing at least sixty of the series), with Warren Murphy, left the series as Murphy did and turned to writing on his own using the name recognition from the critically praised men’s action series as a stepping stone. His first big title, The Quest, about a modern secret war over the Holy Grail, got great reviews and had big sales and was followed up by The Body (filmed with Antonio Banderas) about a shocking archaeological discovery, a spy novel, and this one, Far Arena.

I’m not sure if this is his last book, but it is one of his last and had hardcover, book club, and paperback editions. While structured as a thriller, Far Arena is often a sharp satirical jab at modern society and a historical novel with a unique perspective as a modern thriller.

The characters are well drawn, and the relationship that develops between Eugenianus and Sister Olav believably drawn. Eugenianus’s shock when he returns to Rome is one of the novel’s highlights, possibly the most devastating lesson in “you can’t go home again†you will encounter in a thriller.

Far Arena is different, a variation on the Berkeley Square theme or Edwin Lester Arnold’s Phra the Phoenician (the John Carter reference has to do with the Edgar Rice Burrough’s character’s penchant for traveling across time and space in ethereal form) certainly, but an entertaining and even thoughtful read, just the sort of thing for a cool fall night on the run up to Halloween.

Wed 3 Oct 2018

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Something unusual happened to me last month. For no particular reason I had decided that the subject of my September column should be that jolly old warhorse Bulldog Drummond. No sooner was the column ready for posting than, likewise for no particular reason, I pulled down from my shelves one of the earliest of the almost 600 novels written by John Creasey (1908-1973).

Would you believe? That book was so closely related to what I’d just finished writing up that I could easily have tacked several hundred words about it onto my previous column if I’d felt like supersizing the thing. Well, I didn’t. Here those words are now.

FIRST CAME A MURDER (London: Andrew Melrose, 1934) was Creasey’s fifth published novel and the third in his long-running series about Department Z or, as he called it in the early years, Z Department. All 28 Z novels contain an occasional scene in the office of Department head Gordon Craigie but in most of their pages we follow one or more of Craigie’s agents.

In FIRST CAME A MURDER the name of the agent is Hugh Devenish, who with minimal change might easily have been another gentleman adventurer of the period with the same first name and seven different letters after the initial of his last—a gentleman who happens to have been the subject of my previous column. I don’t have the hardcover edition of 1934 nor the revised U.S. paperback (Popular Library pb #445-01533-075, 1972) but I do own a copy of the British paperback (Arrow pb #937, 1967) for which Creasey revised the original text.

We open, as the title unsubtly suggests, with a murder. In the reading room of the Carilon Club in London’s Pall Mall, a certain Mr. Carruthers who had recently suffered heavy losses in the stock market is stabbed in the neck with a hypodermic needle filled with a poison called adenia which I gather Creasey made up out of (dare I say it?) whole cloth.

There’s no mystery about who done it: the murderer is Rickett, the Club secretary. A week later, that prosperous man-about-town Hugh Devenish happens to have a casual conversation at the same club with Hon. Marcus Riordon, a wealthy obese financier who seems to have been made in the image of the young Charles Laughton. Discussing the recent murder in the club, Marcus describes the locus of the fatal stab as Carruthers’ neck.

Instantly Hugh’s ears prick up; for, as we learn a few pages later, every newspaper report of the crime falsely declared that the injection had been in Carruthers’ wrist. Don’t ask why this deception on the part of the British press, which is never explained or even discussed, but it’s the springboard for everything that happens from then forward including an attempt to run down Devenish that same evening by an automobile near the Admiralty Arch.

As chance would have it, Department Z is investigating the murder for its own reasons, and soon Hugh is eyebrows-deep in a rather vague plot by Hon. Marcus and a gaggle of henchmen to convert their ill-gotten gains into gold and jewels and sneak the loot out of England in a high-powered boat disguised as a tramp steamer. The final chapter, like that of the original BULLDOG DRUMMOND (1920), finds the Hugh D. of this novel marrying the young woman he saved from the brink earlier in the book.

According to a brief foreword to my edition, Creasey made his revisions in 1967, at a time when he’d become rich and famous and a household name among mystery lovers. This doesn’t mean he revised it very carefully. We are told in Chapter 1 that the newspaper Carruthers is reading just before his death is the Star but, according to an official report summarized in Chapter 3, the paper he was perusing was the Sun.

At the beginning of that chapter the structures surrounding Department Z’s headquarters are described as “towering precipices of brick and mortar.†I can imagine Creasey in 1934 writing at such white heat that instead of “edifices†he inadvertently used a sound-alike, but why didn’t he catch the gaffe a third of a century later?

At one point Hon. Marcus plots to have a car similar to Hugh’s and bearing his license plate set on fire with an unrecognizable body inside which was supposed to be identified as Devenish, but the point of the ploy is impenetrable because the real Hugh remains untouched.

FIRST CAME A MURDER was reviewed in the London Times by none other than Dorothy L. Sayers, who described it as a representative specimen of “the thriller with all its gorgeous absurdities full blown.†She said nothing about any of the flaws I’ve mentioned but pointed out that under the British nobility’s nomenclature rules it was impossible for Marcus, “the son of a dope-sniffing baronet,†to be an Honourable. Creasey left his villain’s title as it was: “I confess to a positive liking for those ‘gorgeous absurdities’, and I could not bring myself to remove any of them.†Which leaves us wondering what if anything he did remove or replace. Sayers’ comments about this book in 1934 apply just as surely to the 1967 version I read.

The earlier chapters of FIRST CAME A MURDER are perhaps a little light on action but the second half, where something is happening on virtually every page, more than makes up the deficit. The exact opposite is true of the next book I pulled down from my shelves, John Rhode’s THE FATAL POOL (1960), in which almost nothing happens, and the little that does has all the flavor of boiled grass.

In the first two pages, which required me to construct two family trees in order to keep track of everyone, we are introduced to (if I’ve counted right) sixteen characters, of whom six are dead and several more are alive but seldom or never appear. (One of the latter is said to be 55 years old — in other words, to have been born in or around 1905 — and also to have served in World War I. What, did they have drummer boys in that war?)

The most recently dead among the cast is a young woman whose drowned body is brought into the dining room of Framby Hall at the bottom of page three. Yvonne Bardwell, notorious for getting engaged to men and then breaking up with them for no reason, has been one of the guests at a house party along with several other relatives of Col. Gayton, the Hall’s present owner, and a few non-relatives such as the professional birdwatcher who loves to go out at dawn and take home movies of rarae aves.

Marks on Yvonne’s shoulders suggest that she was held underwater in the Hall’s outdoor swimming pool, originally part of a moat, in which she was accustomed to take a dip every morning before breakfast. The baffled local officials call in the Yard, and that afternoon Superintendent Jimmy Waghorn makes the first of a staggering number of train journeys from London to the town of Pegworth near which the crime took place. There follows an orgy of talk talk talk, in which nothing much is learned and no destination reached.

On each of the next several Saturday evenings Waghorn reports his lack of progress to the other dinner guests of Rhode’s long-running series character, that ancient curmudgeon Dr. Priestley. At last there comes a development — the murder of the birdwatcher, perhaps as the result of trying to blackmail whoever drowned Yvonne Bardwell — and things begin to move, albeit at a snail’s pace, until at Priestley’s suggestion Waghorn confronts one of the cast, who confesses handily in abundant detail, revealing one of the least plausible murder motives I’ve ever seen, before conveniently giving the book’s title a new meaning.

There are some who love the plodding British whodunit writers that detractors like to call the humdrums and there are some who can’t abide them. Everyone agrees, however, that in the forefront of the group stands Major Cecil J.C. Street (1884-1964), the author of 70-odd novels as John Rhode and another 60-odd as Miles Burton.

(May I pause here to pat myself on the back? More than half a century ago I was the first to point out that Rhode and Burton must inhabit the same body. I based this conclusion on the fact that in every book under either byline, whenever anyone is asked a question the answer is always always always followed with the information that he or she “replied.â€)

My own view, which I’ve expressed in several columns over the years, is that many of the Rhode novels of the Thirties and early Forties are quite readable and interesting but most of the others are dreadful. THE FATAL POOL, apparently second-last in the long-running Dr. Priestley series, has been trashed even by the staunchest fans of the humdrums. Barzun & Taylor in CATALOGUE OF CRIME (2nd edition 1989) called it “The dullest conceivable Rhode…. Well-nigh unreadable.â€

With his usual hard-wired kindness, Anthony Boucher in the New York Times Book Review (26 February 1961) described it as “a moderately good example†of the long-running Priestley series. For my money the line that best does justice to it is one Tony himself perpetrated a number of years earlier, labeling a different Priestley novel “the dreariest Rhode I have yet traversed.â€

There are many such Rhode’s, I fear. To maximize your chances of finding a satisfactory book by this author, best stick with the ones dating from when FDR slept in the White House.

Wed 3 Oct 2018

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

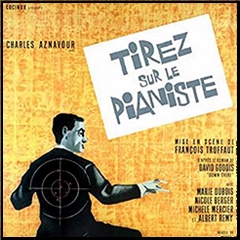

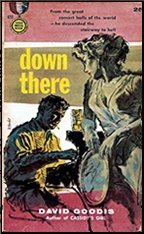

DAVID GOODIS – Down There. Gold Medal #623, paperback original; 1st printing, January 1956. Also published as: Shoot the Piano Player, Black Cat, 1962. Reprinted several times under both titles.

SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER. Les Films de la Pléiade, France, 1960, as Tirez sur le pianiste. Astor Pictures Corporation, US, 1962 (subtitled). Charles Aznavour, Marie Dubois, Nicole Berger and Serge Davri. Adapted by Francois Truffaut from the novel Down There by David Goodis. Directed by Francois Truffaut.

In substance, Down There is pretty typical Gold Medal stuff, what with fist-fights, chases, mobsters, broads, and other rugged manly stuff –- the story is something about a threadbare piano player (Eddie in the book, Charlie in the film) at a seedy bar getting involved with gangs and a waitress — but flavored here with the boozy poetry unique to David Goodis. Goodis could hear the circular logic of a drunk and find in it the awesome redundancy of a Beethoven composition. His characters keep trying to grapple with the meaning of it all, keep losing, keep grappling….

Oftentimes they succeed in resolving whatever the plot is – they catch the killer, foil the criminal, rescue the damsel – only to lose some more important objective, stuck in whatever personal swamp they started out the book in. So the final lesson of Down There is not just that You Can Go Home Again: your destiny was to never really leave.

Shoot the Piano Player takes the fatalism of the novel and infuses it with director Francois Truffaut’s soft heart and Charles Aznavour’s masterful sang-froid.o The circular story is still there, faithfully filmed from the novel down to small detail, but it seems somehow more human, as if it isn’t fate so much as the characters themselves that leads them to their predestined ends.

Aznavour dominates the film, but along the way there are plenty of pauses for the bit players to get out and stretch their legs a bit –- stock characters in Goodis novels and Truffaut films simply refuse to behave like stock characters -– so when Charlie (Aznavour) and Lena (Marie Dubois) are kidnapped by gangsters early on, their captors end up swapping jokes with them. And later on, a thuggish bartender muses aloud about his bad luck with women as he’s trying to choke Charlie to death.

The point, if there is one (it’s never quite safe to go looking for a moral lesson in Truffaut films or Goodis novels) may be that no one is really ordinary: not in pulp novels, B-movies or what we call Real Life; skid-row bums might be heroes, goons can feel tenderness, and a spear-carrier in the back row of Aida may actually be singing an aria, if we listen closely.

“Charlie old buddy – may I be familiar? – Charlie old buddy, I’m going to kill you.â€

Mon 1 Oct 2018

ROBERT SHECKLEY – Live Gold. Stephen Dain #3. Bantam J2401, paperback; 1st printing, July 1962.

I’m not sure, but Live Gold may be unique in the annals of detective fiction. We know the villain from very early on. In fact over 90 percent of the story follows along with him on his latest arduous journey across northern Africa, circa 1951-52, with a contingent of perhaps 400 very indigent Muslims on their once in a lifetime pilgrimage to Mecca.

Or so they believe. What they do not know is that their guide, Mustapha ibn Harith, is leading them instead straight into slavery. Live gold.

What we the reader do not know is which one the seven Europeans traveling with them is the international agent Stephen Dain. Each and every one might be the man, but neither Harith nor his sycophant assistant, a Greek named Prokopulous, can determine which one he is — and their attempts to do so form the thrust of the story.

Robert Sheckley was, of course, far better known for his long career of writing witty and often outright comic science fiction, usually in the short story form. The wit is often present in this, Dain’s third recorded adventure. I don’t think Sheckley could have stopped himself if he had tried. It’s subtle, though, and a reader unfamiliar with his style of writing may not even notice.

What I found amusing personally, for example, was Sheckley’s apparent fondness for place name dropping, a trend that takes place every so often throughout the book. Take this passage from page 109:

[On] the third day of Dhu ’l-Hijja, the train had reached Kosti on the White Nile and was speeding eastward past the cotton fields of the Gezra. At noon the train passed Sennar Dam on the Blue Nile and turned north toward Medani and Khartoum.

After a while one begins to wonder if Sheckley had ever been near any of these places. The alternative, of course, is that he had a really good atlas at his disposal.

The Stephen Dain series —

Calibre .50 (1961)

Dead Run (1961)

Live Gold (1962)

White Death (1963)

Time Limit (1967)

« Previous Page