February 2022

Monthly Archive

Sun 20 Feb 2022

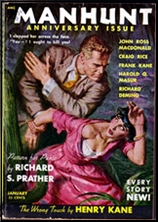

ROSS MACDONALD. “Guilt-Edged Blonde.†Lew Archer. Short story. First appeared in Manhunt, January 1954, as by John Ross Macdonald. Reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, February 1974. Collected in The Name Is Archer (Bantam, paperback, 1955), also as by John Ross Macdonald. Two stories were added to the collection when it was reprinted by Mysterious Press as Lew Archer: Private Investigator in 1977 under the name Ross Macdonald. Reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carrol & Graf, 1988), and in Hard-Boiled: An Anthology of American Crime Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini & Jack Adrian (Oxford Press, 1995). Film: Le loup de la côte ouest (The Wolf of the West Coast), France, 2002. [James Faulkner played protagonist “Lew Millar.â€]

PI Lew Archer is hired for a six day job as a bodyguard for a man who is afraid to leave his house after receiving a phone call that morning. He’s met at the airport by the man’s brother, but the job doesn’t last all that long. When they reach the house, they find his client shot and dying outside on the lawn and a blonde-haired girl driving away in a hurry.

After Archer persuades the brother to pay him to stay on the case, he learns that the dead man had a past. He’d been a treasurer for the mob in his younger days, and it’s apparent that his past had finally caught up with him. The brother, though, is also clearly trying to cover up for the girl.

After tracking down the girl and learning what she tells him, Archer finds himself unlucky with a client a second time. He’s also been shot, and Archer finds him dying outside his home. I won’t go into details, but this is an early version of the stories involving dysfunctional families and their secrets that Ross Macdonald became famous for, and even as short as it is, it’s one told well.

Sat 19 Feb 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[7] Comments

REVIEWED BY DOUG GREENE:

ISAAC ASIMOV – Casebook of the Black Widowers. Doubleday Crime Club, hardcover, 1980. Fawcett Crest, paperback, 1981.

After three books about the Black Widowers, containing 36 stories (and no indication that the series is nearing its end), it’s time to pay tribute to Isaac Asimov’s accomplishment. Though the stories are often compared with Baroness Orczy’s The Old Man in the Corner, they seem to me to belong in a different area of the so-called mystery story.

The Old Man is fundamentally a detective, though an intuitive one who is seldom interested in evidence. Henry, who solves the problems in the Black Widowers stories, interprets word-plays, conundrums, anagrams, without worrying about crimes or indeed rarely about anything more significant than the word-play itself.

Perhaps this point will become clearer if I do two things which The Poisoned Pen has always rightly abhorred: I shall become dryly academic while at the same time, grossly oversimplifying a complex matter.

To pontificate: There is a continuum of types of fiction dealing with the unravelling of a problem:

Riddleâž” Puzzleâž” Mysteryâž” Detection

A Riddle is limited to elucidating a single point, often related to how a word is used, or how a single object or an event can be viewed from an unexpected angle. A Puzzle normally involves more than one occurrence or one word, but it is still usually limited to a small part of the characters’ lives. The Puzzle story shades almost imperceptibly into the Mystery, the main distinct:ton being the significance of the problem to be resolved. Unlike the Puzzle, a Mystery involves most aspects of the characters’ lives, at least as reflected in the story. A Mystery becomes Detection when one character gathers evidence in a systematic (and normally, though not always, active) way.

End of lecture.

Back to the point: The Black Widowers stories are almost always riddles, occasionally puzzles, and never mysteries or detection. As such they fit into the grand line of tales going back to Anglo-Saxon riddles (and probably earlier), and they should not be criticized for being gimmicky or based on tiny points.

When Barzun and Taylor said that the Black Widowers tales are “something of a stunt” (The Armchair Detective, January 1978), they were entirely accurate — but in making such a statement a negative criticism, they were judging riddle stories by the-wrong standard. Asimov’s work should be judged on two· grounds: First, how good a riddle is posed; second, how convincing or entertaining are the surrounding parts of the tale.

To take the latter point first: Asimov’s male-chauvinist club is very well handled. The various characters are well-delineated. The conversations are · not only fascinating for themselves but they often set the tone for the problems; note especially the first Black Widowers volume in which The Iliad is retold in limericks and other lively topics are introduced.

On the other hand, the stories as stories (rather than merely as riddles) are rather static. Despite the presence of a different guest in each tale, the stories vary little and seem rather remote from human worries and from human activities.

Asimov might be wise in future tales to vary the setting or make the riddles more immediate to the Widowers. (But Asimov would probably rightly retort that such changes would produce something entirely different from a riddle story.)

It is in the first point, the riddles themselves, that Asimov shines. The stories are filled with delicious puns and word-twists. The strongest tales are based on new ways of looking at familiar objects.· At times, as with “None So Blind,” the reader should reach the answer before Henry. At other times, as with “The Cross of Lorraine,” “The Missing Item,” and “To the Barest,” the answer is a surprise yet perfectly fair and, once it is revealed, perfectly obvious.

The Black Widowers tales are the best series of riddle-stories now being produced, and perhaps the best ever produced. Long may they continue.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 3, Number 6 (December 1980).

The Black Widowers series —

1. Tales of the Black Widowers (1974)

2. More Tales of the Black Widowers (1976)

3. The Casebook of the Black Widowers (1981)

4. Banquets of The Black Widowers (1984)

5. Puzzles of the Black Widowers (1989)

6. The Return of the Black Widowers (2003)

Fri 18 Feb 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[9] Comments

IT IS PURELY MY OPINION

Reviews by L. J. Roberts

JANE HADDAM – Not a Creature Was Stirring. Gregor Demarkian #1. Bantam, paperback original, 1990. Doubleday, hardcover, 1993.

First Sentence: “Listen,” Myra said, as soon as the phone was picked up, without waiting to find out who had answered it.

Gregor Demarkian, a retired profiler for the FBI “…the most Irish Catholic organization in the U.S. government” is asked for a special favor by his good friend, Father Tibor. Philadelphia Main Line millionaire Robert Hannaford has offered the priest $100,000 for his crumbling church if Gregor will have Christmas dinner at “Engine House,” the Hannaford estate.

What Gregor finds is a house with every inch decorated for Christmas; a group of siblings who don’t like themselves or one another, some of whom are in financial and or legal trouble, and a matriarch crippled with Muscular Sclerosis who never leaves her room. Shortly after arriving, Hanniford is found in his den where a marble bust accidentally fell, killing him. Was it an accident? Gregor doesn’t think so.

Haddam’s voice is one that captivates. With a heading of “PART ONE SUNDAY, DECEMBER 18-SATURDAY DECEMBER 24 THE FIRST MURDER,” it’s clear there’s an interesting story ahead. And it is nice that a floor plan of the house is included at the beginning of the book. The story is filled with subtle, often dialogue-driven humor. There is a cynicism and sharpness to her voice that causes frequent chuckles— “No intelligent psychopath had to murder a dozen little old ladies to get his kicks. He would wreak far more havoc by going into government work.”

After that, it is the character of Gregor and his friend Father Tibor who are the hook. We learn of Gregor’s past and about life within an Armenian community. As for the family/victims, they are a mess. It is hard to work up a whole lot of sympathy for them. It makes one glad to not be wealthy, or at least, overly entitled.

As for the plot, in the end, aren’t all motives really quite basic? The family Gregor is investigating is filled with unpleasant characters, and none more so than the father. As the investigation proceeds, it is understandable why he was murdered.

One point of interest is that each of Haddam’s 30 books, is set against the background of a holiday. This somehow truly fits with her sense of humor.

Not a Creature was Stirring is a familial version of Agatha Christie’s And Then There None. It has a strange, obscure plot of even stranger, mainly unsympathetic people other than those surrounding Gregor. However, what it really has is a delightful voice, eminently quotable lines, and a lot of smoking: one forgets how prevalent smoking was in 1990.

This was one of those books where you feel as though you should have figured it out, but didn’t. It’s also a book that makes one really want to continue the series.

Rating: Good.

Thu 17 Feb 2022

CARTER DICKSON “The Footprint in the Sky.†Short story. Colonel March. First published in The Strand, January 1940, as “Clue in the Snow.†Collected in The Department of Queer Complaints (Morrow, hardcover, 1940). Also collected in Merrivale, March and Murder (IPL, hardcover, 1991) as by John Dickson Carr. Reprinted in Murder in Spades, edited by Ellery Queen (Pyramid, paperback, 1969), also as by Carr.

Strictly speaking, perhaps, not a locked room mystery, but an impossible crime, once you accept the fact that the young girl framed for the crime is innocent, a premise hard to believe, given the facts. A woman living in the house next door, separated by a tall hedge, has been clubbed several times on the head and robbed. It has snowed overnight and the only footprints going back and forth between the two houses are hers. She has size four shoes and the bottoms of hers are soaking wet.

Carr’s books and stories are always permeated with eerie settings and backgrounds, and this one is no exception. The girl is known for sleepwalking and waking up having no idea what she may have done while doing so. For all she knows, she may have done it. Only Colonel March, head of Scotland Yard’s Department of Queer Complaints, believes her story at once, as soon as he’s on the scene.

Carr was also known for playing “fair†with the reader, and again this one is no exception, but only once the reader, as soon as the rather outrageous solution is revealed, says, “Hey! What?†(quoting me exactly) and goes back into the story to discover what it was the March used to base his deductions on. Sure enough, it’s there. Right in plain sight, but totally buried in a paragraph used quite innocuously to describe a room.

Note my use of the word “outrageous†in the paragraph above. I still don’t believe what he says happened could actually be done, but I guess I’d have to grant you that it *could* have.

Wed 16 Feb 2022

QUILLER. “The Price of Violence.†BBC, 60 minutes. 29 August 1975. (Season 1, Episode 1.) Michael Jayston (Quiller), Moray Watson (Angus Kinloch). Guest Cast: Sinéad Cusack, Ed Bishop. Screenplay: Michael J. Bird, based on the character created by Adam Hall (Elleston Trevor). Director: Peter Graham Scott. Currently available on YouTube.

It’s been over five years since the greatly missed Michael Shonk reviewed Adam Hall’s Tango Briefing, the fifth adventure of the master spy known only as Quiller. Along with that review he discussed the BBC TV series based on the books. At that time, only three of the episodes were known to have survived. Lo and behold, the whole season has recently turned up, easily found by doing a search for them on YouTube. I only wish that Michael were still with us to see them.

There is much to like in “The Price of Violence,†the very first episode, but something I found as awfully rough going was that there is no dialogue at all in the first nine minutes, only scenes of some of the usual Mideast violence in Israel and Lebanon. Without knowing who any of the characters are, or — truthfully — no idea of what is happening, it all goes by too vaguely and with no particular context or meaning, then only to be forgotten once the story itself begins.

Which has Quiller home in disgrace, his mission in the war zone a failure. As a penance, he’s not cashiered outright, nor put in a desk job, but put into a state of semi-limbo instead, a situation to which he does not take kindly. But his immediate superior (played impeccably well by Moray Watson), as well as the director of the totally secret “Bureau,†have other plans for him, and he’s ever so subtly nudged into becoming the bodyguard of the head of the World Food Commission, a totally innocuous man who otherwise has no play in the proceedings.

Involved, however, is the man’s legal advisor, played to perfection by Sinéad Cusack, and sparks between Quiller and herself fly immediately. (She was to turn up again in two later episodes.) Quiller is a loner and a cynic, but as a man deeply involved in the spy business, never carries a gun. The sad but steely-eyed Michael Jayston was made for the part. George Segal, who played Quiller in the movies, was not.

The series lasted for only one season of thirteen episodes, all now available, at least for the time being.

Tue 15 Feb 2022

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Crider

DAN CUSHMAN – Jewel of the Java Sea. Gold Medal #142, paperback original, 1951. Cover artist: Barye Phillips. Two later printings. Expanded from the short story of the same title appearing in Adventure, October 1948. [See Comment #5.]

Dan Cushman wrote a number of novels for Gold Medal in the 1950s, most of which were referred to by the publisher as “jungle thrillers.” The books were distinguished for their exotic settings in faraway lands. Jewel of the Java Sea, for example, begins in Borneo, moves to Singapore, and concludes in Sumatra.

The story involves Frisco Dougherty, who has spent the last fifteen years in the tropics, hunting for a fortune in stolen diamonds. He obtains the first diamond easily because of his slightly shady reputation, and he knows there must be others. If he can find and sell them, he can return at long last to San Francisco and feel the cold fog in his face once more.

The search is hampered by the presence of other hunters, including Deering, a murderous American, and his Sikh retainer. And of course, as in any good paperback of the time, there are three beautiful women of doubtful loyalties and morality.

The pace is fast and the local color well done and convincing. The book is slowed somewhat by the dialogue, Dougherty being devoted to reading Boswell’s Life of Johnson and apparently having let his reading affect his speaking, and the relationship between Dougherty and one of the women is a little too spontaneous; but there is a fine treasure story (undoubtedly influenced by The Maltese Falcon), and the ending is satisfactory enough to make one forgive minor quibbles.

Other Cushman “jungle books” include Savage Interlude (1952), Jungle She (1953), Port Orient (1955), and The Forbidden Land (1958).

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Tue 15 Feb 2022

WILLIAM CAMPBELL GAULT “Stolen Star.†Short story. Joe Puma. First published in Manhunt, November 1957. Reprinted in The Mammoth Book of Private Eye Stories, edited by Bill Pronzini and Martin H. Greenberg (Carrol & Graf, 1988). Collected in Marksman & Other Stories (Crippen & Landru, 2003).

I may have this totally wrong, but even though PI Joe Puma’s home base is southern California, I don’t remember many of the novels and other fiction he was in involving Hollywood and the world of glamorous movie stars, beautiful starlets, and famous directors.

I think of him rather as a blue-collar kind of guy, so my sense is that his brushes with the film industry were at the lower ends of it: chiseling movie producers at independent studios, conniving agents, and the like. Maybe I’m wrong, but at least in “Stolen Star†he gets to bump elbows (so to speak) with some of the major players in the industry which keeps all those millions if not billions of entertainment money flowing into the L.A. area.

And even that may be an exaggeration: “Laura Spain had been kidnapped. Laura wasn’t the youngest star in the business, but she still had her figure and enough looks to pull all the men over thirty into any theatre showing one of her pictures. […] The thing had a bad odor right from the first ransom note.â€

Or in other words, maybe Laura thinks she’s slipping. That her career needs a boost, however sketchy the plan may be.

Even though he smells something wrong, Puma agrees to be the go-between in getting the money to the kidnappers. And he’s right. Things do not work out well, and making what goes wrong as right as he can is the rest of the story. As always in these early stories, written just after the pulps died, Gault’s prose is snappy and smooth and goes down awfully easily.

I do wish, though, that he had let the reader know more what Puma learns when he learned it, and even then, there’s a bit of jump between knowing it and knowing exactly who did it and why. I hope I don’t sound overly picky about this. It’s a very good story.

Mon 14 Feb 2022

REVIEWED BY DAVID VINEYARD:

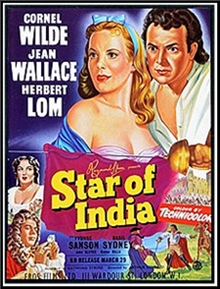

THE STAR OF INDIA. Eros Films, UK, 1954. United Artists, US, 1856. Cornell Wilde, Jean Wallace, Herbert Lom, Basil Sydney, Yvonne Sanson, John Slater, Walter Rilla. Screenplay: Herbert Dalmas, Denis Freeman (additional dialogue), John H, Kafka (uncredited). Directed by Arthur Lubin.

Gorgeous color and the scenic haunting mystery-ridden landscape of the Languedoc region of France are among the highlights of this 17th century swashbuckler featuring Cornel Wilde as Pierre St. Laurent, a French officer recently returned from the wars in India (when the French and Dutch were still vying for an Indian Empire with the British) whose homecoming is spoiled when he finds his home has been sold for taxes and is now occupied by Katrina (Jean Wallace, Wilde’s wife), the widow of an older Count.

When a visit to the ruthless and feline Royal Governor of the region Narbonne (Herbert Lom) yields no relief, Pierre returns to Katrina who informs him the Count sold a family jewel to Narbonne to pay for the estate and that if he will return the jewel, she will return his estates.

That night when Pierre steals a statue of Shiva from Narbonne, he is forced to kill another thief who dies whispering the name of the king, and when the statue in turn houses only an empty compartment, Pierre is convinced Katrina’s story is about a family jewel is a lie — certainly when the jewel in the painting of her grandmother turns out to have been only recently added to the portrait and is a different shape than the hidden compartment in the statue.

Spying on her, he learns that she is an agent of the Dutch government in the person of Van Horst (Walter Rilla), and the jewel is none other than the sacred sapphire known as the Star of India stolen by agents of Narbonne in India from a temple which the Dutch government wishes returned to India, where the jewels theft has stirred riots and unrest and death among native and colonists alike.

Shades of The Moonstone and The Sign of the Four.

Pierre manages to get himself invited to stay with Narbonne by returning the statue of Shiva, claiming to have stopped the thief he killed with a promise from Narbonne he can present his case to Louis XIV (Basil Sydney) himself. But he soon discovers that Louis, who is traveling with his Mistress Madame de Montespan (Yvonne Sanson), wants the jewel for her (and already sent the thief Pierre killed to steal it from Narbonne).

Now Pierre must choose between his king, his conscience, and his growing love for Katrina if he can discover where Narbonne has hidden the jewel, steal it from under the eye of Narbonne, his man Emile (John Slater), and the greedy king (well played by Sydney).

It’s a clever film with an attractive cast made even better by Wilde, a natural swashbucker (Bandit of Sherwood, At Sword’s Point, Forever Amber, Treasure of the Golden Condor, Sword of Lancelot) and a gifted swordsman (he qualified for the 1936 Olympic fencing team but never competed), who was as at ease as Errol Flynn in this type of role.

There were always complaints about Wallace role in Wilde’s films, but while she was no great actress, she was photogenic and competent and certainly the films are better than those Hugo Haas put Cleo Moore in, and I would argue she is better than Sondra Locke in most of Clint Eastwood’s films and at least as good as Jill Ireland in Charles Bronson’s. As nepotism goes it seems a lesser sin.

The film might have fared better with Maureen O’Hara or Rhonda Fleming, but Wallace is more than adequate, and between Wilde’s swashbuckling, Lom’s villainy, a smart script, capable direction by Lubin (Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves with Wilde and many Abbott and Costello films and later television), attractive sets, well staged action, and the too seldom seen Languedoc scenery, the film has more than enough going for it to compensate.

If, like me, you like a good swashbuckler this one is relatively rare and quite worth the effort to see. I don’t know if it is available on DVD, but you can find it streaming on YouTube in English with not too distracting foreign subtitles in a decent enough print.

Sun 13 Feb 2022

ELLERY QUEEN – The Devil to Pay. Stokes, hardcover, 1938. Pocket #270, paperback, 1944. Reprinted many times, including as one of the three novels in the omnibus volume The Hollywood Murders (J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1951). Also note: The Perfect Crime (Grosset & Dunlap, hardcover, 1942) was a novelization of the film Ellery Queen and the Perfect Crime (Columbia, 1941), which in turn was loosely based on this novel.

Ellery, as Hilary “Scoop†King, the wildest type of parody of a newspaperman, solves the murder of a crooked financialist, Solly Spaeth. After disastrous floods in the Midwest, Ohippi hydroelectric project collapsed, leaving all other stockholders ruined, including Spaeth’s partner. There is also the matter of the correct will, so there are plenty of motives.

A smooth, easy flow of words, a well-coordinated plot, and as “unlikely†but fairly obvious choice of murderer makes for enjoyable reading. However, there is nothing much to remember it by – I presumably have read it before, but nothing came back this time. Also included are Ellery’s experiences in trying to see an eccentric Hollywood producer.

Rating: ****

–November 1967

Sat 12 Feb 2022

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[2] Comments

REVIEWED BY BOB ADEY:

BILL PRONZINI – The Vanished. Nameless PI #2. Random House, hardcover, 1973. Pocket, paperback, 1974. Foul Play Press, softcover, 1984.

The second investigation by the nameless detective and the usual polished performance from Pronzini. The prose is a pleasure to read, and the story itself has you reaching for the next chapter. “Nameless” is employed to find a Master Sergeant who has apparently vanished into thin air after returning to his native soil from a final spell of duty in Europe.

The detective interviews those of his friends and former comrades who might be able to help — and falls in love with Cheryl, the sister of one of them. The trail leads.from Oregon to Western, Germany, and from there to Northern California. Along the way Nameless picks up the pieces that eventually complete the jigsaw and uncover the vanished.

The book’s one weakness (if such it be) is that the identity of the criminal can be deduced by reference, not to the clues, but to the inevitability of such a solution in the scheme of things for poor old Nameless.

– Reprinted from The Poison Pen, Volume 3, Number 6 (December 1980).

« Previous Page — Next Page »