March 2024

Monthly Archive

Tue 19 Mar 2024

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

The Amazing Colossal Belgian:

A Quartet of Christie Expansions

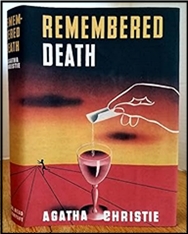

Part 4: Remembered Death

by Matthew R. Bradley

Agatha Christie’s revisions of her Hercule Poirot stories sometimes involved expansion into novels, sometimes involved exchanging one of her many sleuths for another…and, on one occasion, both. “Yellow Iris” (The Strand Magazine, July 1937; Hartford Courant, October 10, 1937, as “Poirot Wins Again”) was first collected in The Regatta Mystery and Other Stories (1939), and it later sprouted into Remembered Death (1945), originally serialized in The Saturday Evening Post (July 15-September 2, 1944) and then published in the U.K. under Christie’s original title, Sparkling Cyanide. Making his final appearance, as the featured detective in that novel, is Colonel Johnnie (aka Johnny) Race.

Despite supplanting him there, Race had been Poirot’s good friend in Cards on the Table (1936) and Death on the Nile (1937), both of which were first serialized in The Saturday Evening Post (May 2-June 6, 1936 and May 15-July 3, 1937, respectively). Embodied by David Niven in the 1978 feature-film version of Nile, Race actually debuted solo in The Man in the Brown Suit (1924), first serialized in the London Evening News, in no fewer than fifty installments (November 29, 1923-January 28, 1924), as Anne the Adventurous. “Iris” was adapted for radio in 1937—by the author, adding the initial article “The” to the title—and 1943, and with David Suchet, in 1991, for Series 5 of Agatha Christie’s Poirot.

Late at night, Poirot receives an urgent call from an unknown woman, a summons to the Jardin des Cygnes, where he is warmly greeted by “fat Luigi.” Having been directed to the “table with yellow irises,” he observes that all others bear pink tulips, and finds it set for six but currently occupied only by his friend Anthony Chapell, who is surprised to see him and mournfully reports that his “favourite girl,” Pauline Weatherby, is dancing with someone else. Soon, they are joined by her; their host, her brother-in-law and guardian, rich American businessman Barton Russell; Lola Valdez, “the South American dancer in the new show at the Metropole,” and Stephen Carter, who is “in the diplomatic service.”

Poirot’s circumspect questions fail to reveal which of the ladies called him, while Barton says it is apt that he has taken the seat left open to honor his wife, Iris, poisoned in New York four years ago that night with the same five present. With the remains of a packet of cyanide found in her handbag, it was presumed a suicide, but Russell says he has long disbelieved it, certain she was murdered by one of those at the table. He leaves to confer with the dance band, and as they launch into the same song that was playing that night in New York, a waiter circles the table in the darkness surrounding the spotlight, filling their glasses with champagne; just as Russell returns, Pauline slumps over, dead the same way.

Finding nothing in her handbag, Poirot announces that there is no need to have everybody searched, and has Tony flip the packet from the pocket of Carter, who said that Lola “had rather a fancy for Barton…in New York”; Russell, in turn, asserts that Iris loved him, and was killed to avoid a scandal. But the ensuing “Resurrection of Pauline” is revealed to be part of Poirot’s plan to expose Russell, who posed as a waiter in the darkness, for a failed murder. Just as in “The Theft of the Royal Ruby” (aka “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding”; 1960), Poirot had conspired with the “victim” to fake her own murder, having deduced that it was she who called, and whispered in her ear when the lights went down.

Poirot tells Russell, “I do not know…whether you killed your wife in the same way, or whether her suicide suggested the idea of this crime to you,” presumably to cover up his misappropriation of funds under his stewardship. Pauline elects not to prosecute Barton, who also dropped the half-empty packet into Carter’s pocket, and is advised by Poirot to “go quickly [but] be careful in the future.” Christie incorporates the lyrics to two original songs: “I’ve Forgotten You” (set to music for ITV’s Suchet adaptation), performed by a hypnotic black girl at Barton’s behest, and “There’s Nothing Like Love for Making You Miserable,” which ends the story as Tony and Pauline happily dance off to “Our Tune.”

Sparkling Cyanide was adapted for television as 1983 and 2003 telefilms and “Meurtre au champagne [Champagne Murder],” a 2013 Series 2 episode of the French Les Petits Meurtres d’Agatha Christie [The Little Murders of…]; for BBC Radio 4 in 2012; and in the Japanese manga album Chimunīzu-kan no himitsu (The Secret of Chimneys, 2006). The novel’s rough analogs are Barton Russell/George Barton, Iris/Rosemary, Pauline/Iris Marle, and Carter/rising M.P. Stephen Farraday. At the Luxembourg restaurant, one year after Rosemary’s death, they are joined by Lady Alexandra Farraday; George’s secretary, Ruth Lessing; and Anthony Browne, who has a “shadowy past and…suspicious present.”

Two couples sit at adjacent tables: Pedro Morales and his girlfriend, Christine Shannon, and Gerald Tollington and his fiancée, Patricia Brice-Woodworth. But before that fateful second dinner party, which begins halfway through the book, Christie devotes chapters to each of the six, explaining their backstories, relationships with Rosemary and/or motives to kill her. When their mother died, 17-year-old Iris went to live with her married sister, who’d inherited a fortune from her godfather, Viola’s failed suitor “Uncle” Paul Bennett; a week before Rosemary died, Iris had interrupted her—recovering from the flu to which her depression was attributed—writing Iris a letter, revealing that it would then go to her.

George suggests that Iris, who inherits on her 21st birthday or marriage, remain living at Elvaston Square and that her paternal aunt, Lucilla Drake (impoverished by the financial claims of black-sheep son Victor), join them to chaperon her in society. Six months later, in a trunk in the attic, Iris discovers Rosemary’s unsent letter to “Leopard,” the lover with whom she planned to go away. Iris believes that he must be either Farraday—said to be a possible future Prime Minister, whose influential in-laws, Lord and Lady Kidderminster, grudgingly let Sandra marry beneath her station—or globe-trotting Browne, unseen since Rosemary’s death, who abruptly reappears only one week after Iris had found that letter.

Tony cultivates Iris, and George, after cautioning her that “nobody seems to know much about the fellow,” begins behaving oddly, buying Little Priors, the Sussex summer house near the Farradays’ Fairhaven. At last, he admits receiving anonymous letters saying that Rosemary was murdered, and if so, it must have been by someone at the table. We learn of Victor planting—or nurturing?—in Ruth’s mind that George should have wed her, not Rosemary; of Browne’s dismay when Rosemary reveals that Victor had outed him as ex-con Tony Morelli, a dangerous secret; and of Stephen’s horror when Rosemary suggested that she and “Leopard” divorce their spouses and marry each other, destroying his career.

While intuiting that Rosemary had a lover, George was uncertain who, and now hopes to ask Race, invited to that first dinner yet unable to attend, his advice about the letters. He tells Sandra that—on a “nerve specialist’s” advice—he is arranging the second to get Iris, never the same since, back onto the metaphoric horse, but admitting her knowledge of the affair to Stephen, she says, correctly, “I think it’s a trap.” Shortly before they are to leave Sussex, Tony surprises Iris by asking her, for reasons she must take on trust, to “come up to London and marry me without telling anybody,” but scoffs at the notion of Rosemary’s being murdered; Tony also sees the arrival of Race, obliquely noting that they “had met.”

George recaps Rosemary’s death, just as in “Yellow Iris,” and admits buying Little Priors because he suspected that her lover was either Stephen or Tony; the latter’s name rings a bell with Race, who wonders what motivated the letters and agrees that, while everybody had a motive, George would be unlikely to rake it all up if he did it. Secretive about his plan, George asks Race, formerly of M.I.5, to attend, yet is warned, “These melodramatic ideas out of books don’t work.” So it seems as Christie takes a hard left and George, who had Ruth deputize Buenos Aires agent Alexander Ogilvie to pay off for embezzler Victor, keels over after toasting, “To Rosemary, for remembrance,” this time sans resurrection…

Race saw nothing suspicious from his table some distance away, and compares notes with Chief Inspector Kemp (who had worked under Superintendent Battle, another second-tier sleuth in Cards on the Table), agreeing that this confirms George’s suspicions. Iris enters as Race interviews Lucilla, announcing her plan to marry Tony, then privately shows him Rosemary’s letter, certain now that “Leopard” was Stephen and she a suicide. Race’s old friend Mrs. Rees-Talbot is the new employer of Barton’s ex-parlourmaid, Betty Archdale, who reports overhearing Tony warn Rosemary she could be disfigured or “bumped off” if she spoke of “Morelli,” a convicted saboteur whom Race realizes is an undercover agent.

Reading of George’s death, actress Chloe Elizabeth West visits Kemp, saying she’d been hired by him to fill the empty seat—coiffed, dressed, and made up like Rosemary—until a call from someone cancelled it; confronted by Kemp about their affair, Stephen insists Sandra knew nothing. A scared Iris tells Tony that in the aftermath, she found planted in her handbag, and ditched under the table, an empty cyanide packet, and he convinces her to fess up to Kemp. After two failed attempts on Iris’s life, both revealed to be the work of Ruth, Tony identifies her as the true target of the second murder, intended to be taken as another suicide, but through a mix-up, George drank from Iris’s glass instead and died.

“Pedro” was Victor, who posed as a waiter while ostensibly making a phone call, and had conspired with Ruth, knowing that if Iris died unwed, her money would go to ever-pliable Lucilla. Christie’s acorn-into-oak job is superb, with the additional suspects and motives well drawn, as are secondary characters such as Lucilla, whose willful self-delusion about Victor is at once amusing and tragic. My only criticism is with the novel’s structure, as it moves backward and forward so often, before and after Rosemay’s death, as to leave this reader (and summarizer) occasionally uncertain as to where he was in that time sequence, a minor quibble in a work that I thoroughly enjoyed, however much I missed Papa Poirot.

— Copyright © 2024 by Matthew R. Bradley.

Editions cited:

“Yellow Iris” in Hercule Poirot: The Complete Short Stories: William Morrow (2013)

Remembered Death: Pocket (1947)

Sun 17 Mar 2024

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

Reviewed by TONY BAER:

MALCOM BRALY – Shake Him Til He Rattles. Gold Medal k1311, paperback original, 1963 (cover art by Harry Bennett). Belmont, paperback, 1971. Stark House Press, softcover, 2006 [published together with It’s Cold Out There].

Hip saxophone player loves his grass. Sick narco cop wants his ass. Tis the story of the cat and mouse between narco and hipster. Spoiler Alert: The hipster wins.

Pros: Told in legit Sixties beat lingo.

Cons: The story is too pat and neat and clean and happy for this noir fan. But hey, nice to see a Gold Medal with a happy ending now and then I guess.

Fri 15 Mar 2024

ROBERT SILVERBERG “Hawksbill Station”. Novella. First appeared in Galaxy SF, August 1967. Reprinted in World’s Best Science Fiction: 1968, edited by Terry Carr & Donald A. Wollheim (Ace, paperback, 1967). First collected in The Reality Trip and Other Implausibilities (Ballantine, paperback, 1973). Expanded to the novel of the same title (Doubleday, hardcover, 1968). Nominated for both the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 1968 for Best Novella of 1967.

Governments of the 21st Century have found Hawksbill Station, located two billions years in Earth’s past, an excellent spot for deported political agitators. Jim Barrett, with greatest seniority, is the acknowledged king whose kingdom is going completely insane. A crisis seems to form with the new arrival of Lew Hahn, who is strangely different.

The ending is a letdown from what goes before, is perhaps too simple in comparison with the masterful construction that precedes. It could be the background for a much longer story.

Rating: ****

— June 1968.

Thu 14 Mar 2024

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[6] Comments

Reviewed by TONY BAER:

RICHARD WRIGHT – The Man Who Lived Underground. Library of America, hardcover, 2021. [Previously unpublished novel from the 1940s. Its only publication in Wright’s lifetime was in Accent, Spring 1942. and then only in drastically condensed form; it was later included as such in the posthumous short story collection Eight Men (1961).] Harper, softcover, 2022.

Black dude gets off work, heading home to his pregnant wife, minding his own business, gets stopped by the cops. Who accuse him of murder.

He’s innocent, but the cops’ll hear nothing of it. They give him the third degree, smack him around til he cannot see, then make him sign a confession.

He escapes custody, leaping into manhole, hiding in the sewers.

While in the sewers, he finds that he’s able to break into basements and get what he needs to survive. And more.

One basement yields a workman’s lunch box with thick pork chop sandwiches and a nice juicy apple. A radio. And a toolbox. Another is the basement of a jewelry store, he pockets a bunch of diamonds and golden rings. Another is a butcher shop where he takes a cleaver. Another has a safe full of cash and coin.

He takes the plunder back to an unused storage basement in a Black church, listening to the hymns, to all the guilt and sighs and cries of the parish as they pray forgiveness for a crime they never done.

What is the meaning of all this plunder, he wonders. The cash has no use for him as he hides out beneath the city. He has all he needs. He wallpapers his dwelling with hundred dollar bills using glue from the tool chest. He hangs the rings on nails he plants in the wall. The diamonds he stamps in the floor, like stars in the sky. In reverse.

Suddenly he realizes that, despite his indignation at being accused of a crime he never committed, we’re all guilty. And the sooner we realize that we’re all guilty, and lay down our arms, our guns, our cleavers, our pride, our defenses, our petty larcenies, our pretense, the sooner this world can be won.

The sooner this world can be one.

So, after a time, he decides to come back up for air. To test his way in the world again.

By this time, the cops have forgotten all about him, having found the actual murderer. But he can’t leave well enough alone. He has to convince the cops that he IS guilty. Perhaps not of that crime but of others. Of taking the jewelry, the rings and the money.

The cops don’t understand him. They figure he’s gone mad. But just the same, can they leave such a madman loose? Or shall he be condemned?

———–

The best thing I’ve read in an awfully long time. Enjoyed it a heckuva lot more than Native Son. It reads like a cross of Cozzens’s Castaway and Kafka’s Trial, with a dash of “The Grand Inquisitor” at the end. It’s realistic enough to be realism, and in fact was based on an actual series of crimes committed underground via a sewer network. But the power of the thing comes from the fact that while it sounds in reality, it sounds equally in allegory. And you (as well as the protagonist) have a sneaking suspicion that something of terrific theological meaning is right at the cusp. This is where Kafka and the Grand Inquisitor come in. Nothing is stated in any express way and no conclusions are reached. But ambiguity yields a power and responsibility split with the reader. You’re left figuring. Forevermore.

The edition I read also had an enlightening essay about the composition of the piece by Wright called “Memories of my Grandmother”. He talks about how, in his work, there are two sections. The first section is BEFORE his character is ‘broken’ and the second section is AFTER they’re broken. Something happens in a novel, perhaps a crime, that rifts the character from their ordinary life. They think they know what life is all about. And then something happens. And they are thrown from their life into a new ambiguity where none of their prior truths hold true.

The character becomes supple in the writer’s hands, like Gumby, and the author can do anything with them at this point. All meaning becomes unhinged and ready to be rehung however you like in a world turned upside down. It’s the best thing I’ve read describing the effectiveness of the crime novel in communicating the experience of absurdity in a world gone noir.

Wed 13 Mar 2024

A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Marcia Muller

LESLEY EGAN – A Case for Appeal. Harper & Brothers, hardcover, 1961. Popular Library, paperback, date?

Lesley Egan is a pseudonym for Elizabeth Linington, who also writes under the name of Dell Shannon. The author is well known for her three series of police procedurals done under these names, and while the procedure is very sound, it is interest in the recurring characters’ lives and personal problems that seems to draw readers to these popular books.

A Case for Appeal introduces Jewish lawyer Jesse Falkenstein and his policeman friend Captain Vic Varallo. Varallo has called Jesse away from Los Angeles to the little southern California valley town of Contera to defend accused murderess Nell Varney — a woman Varallo has arrested, but whose guilt he doubts. As the story opens, Nell has just been convicted and sentenced to death for the murder of two women upon whom she supposedly performed illegal abortions. Jesse — who was called in too late to do any investigation or prepare a solid defense- intends to appeal the case. But to make a case for appeal, he must find the woman resembling Nell who really performed the abortions.

With Varallo’s help, Jesse gets to know the families of the victims and the town of Contera itself — no small chore for a Jewish lawyer from the big city. And as he sifts through the testimony, it becomes apparent that deathbed statements from the aborted women can be taken in more than one way, and that someone is manipulating the interpretation of them. A nice romance between lawyer and client, plus Varallo’s conflict about staying in this town where he has come because of his family, a reason no longer valid — provide the provocative personal background that is typical of Egan.

Falkenstein has an odd style of speaking that at first is confusing, but once the reader becomes familiar with it, the story — told largely through dialogue — moves along nicely.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.

Mon 11 Mar 2024

ROGER ZELAZNY “Damnation Alley.” Novella. First appeared in Galaxy SF, October 1967. First collected in The Last Defender of Camelot (Pocket, 1980). Reprinted in Supertanks, edited by Martin H. Greenberg et al (Ace, 1987). Expanded into the novel of the same title (Putnam, hardcover, 1969). Nominated for a Hugo Award in Best Novella category (placed third). Film: 20th Century Fox, 1977, with Jan-Michael Vincent (as Tanner) and George Peppard.

Damnation Alley is the cross-continent route from Los Angeles to Boston, some years after the Bomb. The plague has hit Boston, and Hell Tanner is one of the drivers sent out with the essential serum [they need]. Armored cars are necessary to avoid radioactivity, mutated monsters, and violent storms.

Tanner is an ex-convict, a Hell’s Angel gangleader, who is forced into leading the caravan with the promise of a full pardon. It is his story, his changing reaction to the job he must do, with side glimpses into the resiliency of man. There is, of course, a tremendous build-up of tension and emotion as Boston gradually becomes reachable.

Zelazny’s picture of a new world is both beautiful and horribly terrifying: do you believe that?

Rating: *****

— June 1968.

Sun 10 Mar 2024

Posted by Steve under

Reviews[3] Comments

Reviewed by TONY BAER:

FREDERICK NEBEL – Fifty Roads to Town. Little, Brown & Co., hardcover, 1936. Mercury Book # 33, digest paperback, date? Film: 20th Century Fox, 1937 (starring Don Ameche & Ann Sothern; director: Norman Taurog).

Bunch of strangers get stranded in an Northwoods hotel in a blizzard. Focus is on a nebbish fire extinguisher salesman who’s gone missing. Very 30’s. The interest comes from the interplay between the various types: flapper, repressed aristocrat bent on murdering his rival, his rival, a rugged independent sort, a drunken Nordic dog sled champion, an overbearing housewife, Gilligan and Skipper running the hotel.

—

Just when you think it’s screwball, it turns melodramatic on you. It’s a fairly light invention, with tight dialogue and well drawn characters drawn from central casting. All dressed and ready to be made into a film. With a bow.

I liked it fine, but it’s not why I went looking for Nebel. It’s not hardboiled crime and only vaguely hints at his Black Mask roots. Action and dialogue is economically worded and the thing moves at a brisk pace.

Sat 9 Mar 2024

Posted by Steve under

Awards[7] Comments

Just announced: Aesop’s Travels [as by Daniel Boyd, a pen name of Dan Stumpf] has just won the SPUR Award from Western Writers of America for Best Traditional Western Novel.

https://www.einpresswire.com/article/694525580/western-writers-of-america-accounces-2024-spur-award-winners-and-finalists

I reviewed it here:

A Western Fiction Review: DANIEL BOYD – Aesop’s Travels.

Fri 8 Mar 2024

REVIEWED BY BARRY GARDNER:

KAREN KIJEWSKI – Honky Tonk Kat. Kat Colorado #7. Putnam, hardcover, 1996. Berkley, paperback, 1997.

I think Kijewski is in the group (along with Barnes, Grant, and Rozan) of female PI writers just below Muller and Grafton, and ahead of Paretsky and everybody else. My only quarrel with her lies in her seemingly gender-linked trait of endowing her heroine with obnoxious friends and/ or relatives.

A childhood friend of Kat’s is a country and western star now, and she’s got troubles. Someone is sending her notes that are disquieting and vaguely threatening, and she wants Kat’s help. She’s not being very forthcoming about her past, though, and Kat is having a hard time getting a handle on it all. There’s an abusive ex-husband, a father that vanished when she was two, and a cousin who’s popped up from out of nowhere who wants to be a star, too, and who knows what else. Then someone is killed.

Interesting that Kijewski and Muller both chose a country and western star background for their latest, though there aren’t many other plot similarities. This is a good, solid PI novel, of a piece with Kijewski’s earlier work except for a welcome lessening of Kat’s personal problems and the presence of her aforementioned obnoxious friends and relatives. See, Karen? You can do it.

Good first-person narration, interesting background, good book.

— Reprinted from Ah Sweet Mysteries #26, July 1996.

The Kat Colorado series —

1. Katwalk (1989)

2. Katapult (1990)

3. Kat’s Cradle (1992)

4. Copy Kat (1992)

5. Wild Kat (1994)

6. Alley Kat Blues (1995)

7. Honky Tonk Kat (1996)

8. Kat Scratch Fever (1997)

9. Stray Kat Waltz (1998)

Thu 7 Mar 2024

REVIEWED BY DAN STUMPF:

COMPTON MACKENZIE – Sublime Tobacco. Chatto and Windus, UK, hardcover, 1957.

Nowadays, when smoking is the eighth deadly sin, and smoking indoors constitutes a 4th degree misdemeanor, it’s oddly refreshing to read a book in praise of pure evil.

According to Wikipedia, Mackenzie was well-known in his day as “a writer of fiction, biography, histories and a memoir, as well as a cultural commentator, raconteur and lifelong Scottish nationalist,” and his name is occasionally resurrected today through the miracle of television, as the author of Whiskey Galore and Monarch of the Glen.

This, however, is something completely different (*). A history and personal memoir of the stuff we set on fire, stick in our mouths, and suck on it.

I should say at the outset, it’s mostly rather dull, then hasten to add that the part that ain’t dull is a really great read. And it comes at the beginning, so you don’t have to plow through a lot of soporifics to get there. Sublime Tobacco opens with a quietly rhapsodic mix of tales from the author’s own life and those of his puffing acquaintances: an autobiographical accolade to the stuff of coffin nails,

I was particularly charmed by the account of how he and his brother used to filch Daddy’s cigar butts from the ashtrays and smoke them in homemade pipes. When the old man got wise to it, he went for the time-honored cure-and-punishment: Gave them each a big cigar and ordered them to smoke it down to a stub. Mackenzie’s description of their delight and father’s dismay as the boys smoked cigars (at age 7 and 9) with pure enjoyment, then asked for another is a joy to read. And just as much fun, in a very different vein is his account of how he saved lives by calmly smoking two cigarettes outside the British Embassy in Athens during an anti-anglo riot.

Sublime segues smoothly from anecdotes to critical evaluation, taking time along the way to throw in personal bits of business involving the various and sundry means and methods of filling one’s lungs with noxious smoke. He concedes the convenience of the cigarette, lauds the luxury of the cigar, but like any intelligent man, he gives primacy of place to the Pipe.

Mackenzie’s catalogue of his own pipes, past and present, his analysis of form and function, shape and texture, and his nuanced descriptions of the tastes and aromas of the tobaccos of the world are vivid enough to discolor teeth in an avid reader. This is the work of a truly skillful writer, and his love of the subject is so evident and tender that I felt myself tearing up at times.

Or maybe smoke got in my eyes.

(*) Thanks, Monty Python

« Previous Page — Next Page »