Thu 11 May 2017

COLLECTING PULPS: A Memoir, Part 19, by Walker Martin: PULP ART.

Posted by Steve under Collecting , Columns , Covers , Pulp Fiction[42] Comments

Part 19: Pulp Art

by Walker Martin

I’ve talked before about how I love collecting the original pulp and paperback cover art and illustrations. My feeling is that every book and pulp collector should have at least one example of cover art in their library. I’m not recommending that book collectors go to the extreme that I have gone to with scores of pieces, but it’s a thing of beauty to have a pulp, paperback, or dust jacket cover art framed and hanging on your wall with your book collection.

Recently Steve Lewis was visiting me, and he took over 30 photos, not only of the pulp art but also of other items in my house. This installment should give an example of how one long time collector has dealt with the addiction known as bibliomania. I’ve been at it now since I was a child in 1956. That’s over 60 years!

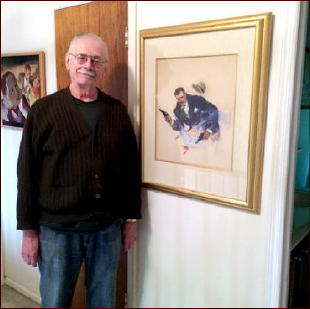

This first photo shows me standing next to my most valuable painting, the cover of Black Mask, for February 1933 by Jes Schlaikjer. Normally, I never would have been able to afford this cover painting because it’s from the classic 1930’s period of Black Mask when the covers showed stark, violent scenes with just a few images. But the seller perhaps did not realize it was a Black Mask cover by Schlaikjer. Over my shoulder is a Lyman Anderson painting for an early 1930’s issue of Alibi.

The second photo is a paperback cover painting by James Avati illustrating a scene from the novel, The Double Door, by Theodora Keogh. Avati was one of the very most influential cover artists in the paperback field, and he was widely imitated. Again, this was a painting that I normally would not be able to afford, but I bought it on credit from an art gallery in NYC.

I’ve often taken out bank loans, used my credit card, paid on the installment plan, in order to feed my art and bibliomania addiction. I’ve never regretted my decision to buy books or art. What I’ve regretted are the books and art that I did not buy!

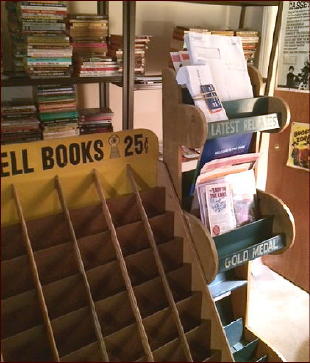

This third photo shows a corner of my mystery paperback room and part of a Dell paperback rack. For decades I hunted for paperback racks from the forties and fifties and finally found five of them at a Windy City show several years ago. They were too fragile to be shipped, and it was two years before the dealer managed to find someone driving across the country in a van to deliver them to my house.

Here below are three more photos of the mystery paperback room. I have the books shelved by alphabetical order except for my Ace Doubles and Dell Mapbacks. The Dell Mapbacks may be complete or close to it. I even found the crossword paperbacks and I wonder how they ever survived? Also pictured is my Bantam Books paperback rack which is in fine condition. The room is very crowded with books, just the way I like it!

This next photo shows two of three large western pulp cover paintings that are hanging by the stairs to the second floor. Back in the 1970’s and 1980’s it was possible to buy western, detective and adventure cover art for very low prices. The three paintings were delivered by a long time collector named Chet Woodrow, who risked driving through a terrible New Jersey snow storm to my house.

Price? A hundred dollars each. Back then I thought such prices were ridiculously low and I still think so. One funny thing about Chet was that he had the worse condition pulp collection that I’ve ever seen. The magazines looked to be in fine condition with nice covers and spines but when you tried to open them the interior pages were very brown and brittle and almost impossible to read.

The Dime Western painting below is from the 1930’s and the artist is the great Walter Baumhofer. Many years ago at an early Pulpcon, I was talking to artist Norman Saunders, and I saw a car drive into the hotel parking lot. I said excuse me to Norman and ran outside where I asked the driver who was not even out of the car if he had any pulp paintings.

He said yes and sold me this painting out of the trunk of his car for only $400. I then went back and showed Norman Saunders the painting that I just had bought in the parking lot and he couldn’t believe that I had just bought an excellent Baumhofer painting out of a car trunk.

We then spent much of the convention in the hotel bar talking about pulp art. I tried to get Norman to sell me some of his paintings, but he was leaving them in his will to his children.

The two bookcases below show part of my extensive DVD collection. I believe these are mainly film noir movies, another my addictions. The crusader painting is from a 1931 Adventure. I got it from the estate of A. A. Proctor, who was the editor of Adventure in the early 1930’s.

Above is one of my favorite pieces of art. It’s a bizarre illustration by Howard Wandrei, the brother of Donald Wandrei. Howard died an early death of alcoholism, but he was a writer of pulp fiction and a sort of outsider artist. This piece fascinates me with its complexity and strangeness. Dwayne Olson has written at least three long book articles on Howard Wandrei, but he is an unjustly forgotten, excellent artist.

The next photo shows me holding the February 1956 issue Galaxy. This is the actual magazine that I bought off the newsstand in Hoscheck’s Deli, and it so impressed me that I became the fiction magazine collector that I am today. It led to my present collection of thousands of pulps, slicks, and digest magazines.

Above is a corner of my son’s former room. For thirty-five years Joe lived with us and then a couple years ago decided to get his own place and moved out. It did not take me long to move into his room and convert it into a library and art gallery!

I have over thirty-five pieces of art in the room and eight bookcases. I think I’m now in every room of the house with art and books. All five bedrooms, the garage which I converted into a library and gallery, the basement, living room, family room. Even the bathrooms and kitchen have art. If I had room I would build another house in the back yard. The large painting is from Detective Fiction Weekly.

This is Paul Herman who has been friends with Steve Lewis and me for quite a while. He’s standing next to a western paperback cover painting.

Above is a corner of dining room with a western painting by Sam Cherry. I love western art, but many collectors seem prejudiced against westerns. They are colorful, full of action, and not as expensive as science fiction or hero art.

Below is another Dime Western painting by Walter Baumhofer showing a girl and cowboy blazing away, back to back. Art dealer Steve Kennedy owned it for many years and would never sell it, but one day he needed money, and I managed to talk him into selling it to me. I seem to remember me whining, begging, and crying. Collectors know no shame!

I’ve told this story before in my article on collecting Western Story Magazine, but the painting below amazingly enough came from my next door neighbor! What’s the odds of a non collector moving next door and having a pulp painting? Took me years to talk him into selling it to me. It’s by Walter Haskell Hinton from Western Storyin the 1930’s.

Above is a row of cover paintings. The first one is from Street & Smith Detective Story. The second one is a Spider cover which was repainted by Raphael Desoto, the original artist. The third one is by Wittmack from People’s.

Another western from one of the Popular Publication pulps. I only paid $400 for it. In the background you can see in the laundry room three of the dozen or so preliminary drawings I have framed. The artist would make a preliminary sketch and if approved would then go ahead and paint the cover. Not many of these survived, but I love them and pick them up whenever I see them. Not many art collectors care about them, but I think they are of great interest.

The next three photos show areas of my basement. The first is an almost complete set of Western Story. Of over 1250 issues, 1919-1949, I need only nine issues.

The second shows some Ace High magazines and the third photo gives an idea of a corner of the basement. The basement is about 60 feet long by 30 feet wide. I’ve filled the entire area with shelving.

In 1989 when I moved into this house I hired a contractor to turn the two car garage into a library and art gallery. These photos show some the area which I’ve filled with artwork, books, and pulps. All the neighbors asked me the same thing. “Why am I turning my garage into a library?” My response was why should I park my cars in my house? But who can understand non readers and non collectors?

More photos of my converted garage taken from different angles. You can see some of the art hanging above the pulps.

The final photo is of me and Steve Lewis. We have been friends for almost 50 years and I’ve been reading the various incarnations of Mystery*File for almost as long. Over Steve’s shoulder is a large painting from The Saturday Evening Post by Harold Von Schmidt. It’s from 1950 and illustrates a scene from a serial starring series characters Tugboat Annie and Glencannon. It was the only time they met in a story, but it has an interesting background.

The Glencannon series were comedies and the Post readers found them hilarious. During the 20 year period of 1930-1950 there were over 60 stories written by the author, Guy Gilpatric. I’ve read them all and they are among my favorite stories. They have all been reprinted in omnibus collections and there was even a British TV series back in the 1950’s.

Unfortunately there was a tragic ending to this comedy series. Gilpatric’s wife was diagnosed with terminal cancer and in a fit of depression they decided on a murder suicide pact. He shot his wife and then took his own life. Later there was a rumor or evidence that the doctors had made a mistake and made the wrong diagnosis.

I obtained the painting from an art gallery by telling the owner that I’d like to get a painting showing my favorite series character, Glencannon. I was stunned when he said he knew where one was, and it turned out to be the best one of them all, the one where Glencannon meets Tugboat Annie. Von Schmidt is a famous western artist, and I’d never be able to afford one of his paintings, but since this was a non-western the price was a lot lower.

So thanks, Steve, for taking these photos and also thanks to Sai Shanker for twice taking photos that unfortunately did not turn out as well. I love reading about the collections of other collectors and maybe this memoir on my art collection will make you decide to become an addicted, out of control bibliomaniac also! I’ve enjoyed the trip and it’s been a great ride…