A 1001 MIDNIGHTS Review

by Bill Pronzini

NICHOLAS BLAKE – The Beast Must Die. Harper, hardcover, 1938. US paperback editions include: Crestwood / Black Cat Detective Series #7, digest-sized, 1943; Dell D227, Great Mystery Library #15, 1958; Berkley F971, 1964; Perennial Library, 1978. First published in the UK by Collins, hardcover, 1938.

British Poet Laureate (1968-72) and novelist Cecil Day Lewis, writing as Nicholas Blake, published a score of popular detective and suspense novels from 1935 to 1968, all but four of which feature an urbane amateur sleuth named Nigel Strangeways. For the most part, the Blake novels are fair-play deductive mysteries in the classic mold and are chock-full of literary references and involved digressions, which makes for rather slow pacing. But they are also full of well-drawn characters and unusual incidents, and offer a wide variety of settings and information on such diverse topics as sailing, academia, the British publishing industry, and the cold war.

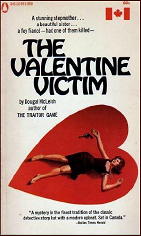

The Beast Must Die is considered by some to be Blake’s finest work and a crime-fiction classic. When the young son of mystery novelist Felix Cairnes (a.k.a. Felix Lane) is killed by a hit-and-run driver, Lane, who doted on the boy, vows to track down and kill the man responsible. A trail of clues leads him to a film star named Lena Lawson, who was a passenger in the death car, and finally to its driver, George Rafferty, the obnoxious part owner of a Gloucestershire garage.

Lane insinuates himself into Rafferty’s household as Lena’s new lover, and makes preparations to exact his revenge via a sailing “accident.” But things don’t quite go as he (or the reader) anticipates. And when murder finally does strike, it does so in a wholly unexpected fashion.

The plot is tricky and ingeniously constructed: the first third is told first-person in the form of Felix Lane’s diary; there is a brief middle section, called “Set Piece on a River,” which is done third-person from Lane’s point of view; and the last half is a straightforward, third-person narrative that introduces Nigel Strangeways (and his wife, Georgia, and Inspector Blount of Scotland Yard) and follows Strangeways as he unravels a tangled web of hatreds and unpleasantries. Blake builds the suspense nicely in the first half, makes good use of a subplot involving Lane’s affection for Rafferty’s own son, Phil, and even spices his narrative with a little sex — an unusual ingredient for mystery novels during the Golden Age.

But The Beast Must Die also has its share of flaws. The manner in which Lane tracks down Rafferty — and the ease with which he is able to meet and seduce a popular actress seem both convenient and contrived; once Strangeways (who is something of a colorless and priggish sort, at least in this novel) arrives on the scene, the narrative becomes talky and slow, diluting suspense; a physical attack on Strangeways is poorly motivated; and the final revelations, intended as a stunning surprise, are neither stunning nor particularly surprising.

This is a good novel, certainly, one worth reading — but it’s not a mystery classic.

A film version of The Beast Must Die was produced in France in 1969 under the title This Man Must Die. Directed by Claude Chabrol, it is faithful to the novel except in one major (and curious) point: It excludes Nigel Strangeways completely and tells the tale as a straightforward thriller.

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.