Thu 6 May 2021

Music I’m Listening To: POSTMODERN JUKEBOX “All About That Bass.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Just for fun:

Thu 6 May 2021

Just for fun:

Wed 5 May 2021

PATRICIA MOYES – Angel Death. Inspector Henry Tibbett #15. Collins Crime Club, UK, hardcover, 1980. Holt, Rinehart &Winston, US, hardcover, 1981. Henry Holt & Co, US, paperback, 1982.

Angel Death is a gripping suspense novel set in Moyes’s fictitious group of Caribbean islands. Inspector Henry Tibbett and wife Emmy are on vacation at the small hotel operated by their friends, the Colvilles; they plan a week’s sailing in a rented boat as well. At the Colvilles also is Miss Betsy Sprague, an interesting and lively old lady. On her first leg of the journey back to Britain she unaccountably disappears after making a phone call to tell the Colvilles that she has spotted the daughter of an old friend, a young woman who is supposed to have gone down with her boat.

Convinced that Betsy has been murdered, the Tibbetts set out to find her killers. In the course of this Henry suddenly changes. His behavior becomes both manic and paranoid. He won’t let Emmy stay on the boat with him; he sends a telegram to Scotland Yard resigning; he takes off sailing with two young couples.

Does he have a plan which depends on this weird behavior? Or has he been drugged? The Governor and police of the islands suspect him of being subverted by drug smugglers, and issue a warrant for his arrest. While this reader was breathlessly wondering how and when Henry would get back to normal, not one but two hurricanes strike the islands.

Emmy has an unwonted opportunity to be a detective on her own. Henry turns up on a foundered boat after the first hurricane, his memory for the intervening time confused and mostly lost. The second hurricane brings it back, Together, he and Emmy foil a plot that is much grander than the smuggling of drugs. As usual Moyes brings her people to life and makes all of this wild action seem quite believable.

Wed 5 May 2021

RED LIGHT. United Artists, 1949. George Raft, Virginia Mayo, Gene Lockhart, Raymond Burr, Henry (Harry) Morgan, Barton MacLane, Ken Murray, William Frawley. Directed by Roy Del Ruth.

Watching old movies like this one, you begin to wonder all sorts of strange things, such as how some actors and actresses became well-known stars, and others didn’t. Take George Raft, for example. Take Virginia Mayo, for another , Neither one could act their way out of a dark room, not if you take this movie as a prime example of their work (and quite possibly you shouldn’t).

Admittedly it’s a low budget crime drama, but that doesn’t stop all of the lower ranked players in the list of credits from showing them how it should be done, if they were paying attention. As the owner of a trucking company whose brother is killed in a bit of gangland revenge, George Raft is as dapper a dresser as ever, but he’s stiff as a board in any small matters such as facial expressions or simply walking across a room.

As for Virginia Mayo, she had the looks and figure to be a star, I suppose, but her delivery here is as wooden as the board that Raft is as stiff as. The real star of this movie is Raymond Burr. In fact this was shown on TNT as part of a afternoon-long Salute to Raymond Burr, which shows that the people at TNT know what they are doing.

Burr is the hoodlum who’s been sent up by Raft, and he’ s the one who hires Harry Morgan to wipe out Raft’s brother. Burr was a little overweight at this time of his career, but his dark, glowering eyes made him a perfect villain in any number of films of this same caliber. Morgan, before he began to make a name for himself in comedy roles, was also perfect as a series of dim-witted killers or former boxers who’d taken one too many on the chin.

Whenever Burr is on screen, the story takes on life. Whenever he’s not, the temptation is to find the fast-forward button. Not a ”noir” film, except on occasion, but in reality an inspirational type of movie, a testament to the practice of leaving Gideon Bibles in every hotel room in the country. (*)

(*) And speaking of Gideon Bibles, it reminds me that the shooting (and a good deal of the subsequent investigation) takes place in the Carlton Hotel, San Francisco. Trivia question: what long-running radio/TV series was there that began almost every episode in the same hotel?

Tue 4 May 2021

HARRINGTON HEXT (EDEN PHILLPOTTS) – Number 87. Thornton Butterworth, UK, hardcover, 1922. Macmillan, US, hardcover, 1922. Wildside Press, US, hardcover/trade paperback, 2008, as by Eden Phillpotts. Prologue Books, US, trade paperback, December 2012.

The first sighting of the creature the world will come to know as the Bat in London is little but a curiosity, but soon it will become a world wide sensation of terror and horror, a monster striking from the sky and leaving death and destruction in its wake.

Eden Phillpotts, who under the pseudonym Harrington Hext penned fantastic thrillers, was a considerable literary light in his day well respected by critics for his regional novels; a recognized master of the mystery novel whose The Red Remaynes (1922) stands with Trent’s Last Case by E. C. Bentley as one of the first novels to create the Golden Age of the Classic Detective Novel; the man who convinced a discouraged Agatha Christie to keep writing because he saw something in her work; who partnered with notable writer Arnold Bennett (Doubloons); wrote early Science Fiction (Saurus and others); lost worlds (The Golden Feitch); and had more literary honors than we can list here, was born in 1862 (and died in 1961).

In the late Victorian Era he made his debut with a pamphlet for a railroad line that both pioneered and popularized an entire sub genre the railroad mystery with My Adventure on the Flying Scotsman, and one of his last novels (1951) featured a murder involving an experimental nuclear physicist . That would be a full career for any writer in any age.

But back to the central question, what is the Bat, and what is the secret of its reign of terror?

Alexander Skeat is the first victim, no mark on him but a tiny red spot. Yes, because this one is no fair play detective novel, a drug unknown to science is the culprit. Indeed in the tradition of the thriller mysterious drugs, monstrous bat winged flying creatures, and enough thrills, horrors, and mysterious doings for a dozen weird pulps fill the pages of this unrepentant extravaganza. Even Edgar Wallace could take a few notes from Phillpotts.

Our narrator is Ernest Granger, the Secretary of the Club of Friends and agent of the Apollo Life Insurance Company, both of who are intimately involved in the history of the Bat. His fellow club members General Fordyce and his scientist brother Sir Bruce, Rev, Walter Blore, Leon Jacobs Stockbroker, and Jack Smith, a barrister all figure in the action.

Drawn into the case by the death of Skeats, a scientific charlatan, the drama will take the men from London to New York, to Yugoslavia (Jugo-Slavia here), Russia, and China in a race to discover what the Bat is and who is behind it, and why it has targeted the relatively new Christian Science movement.

Like many books of the Post WWI era, Number 87 is concerned with the future, the fear of another Great War, and how to avoid that fearful fate.

That voice is key to the solution of the novel, a modern Prometheus (and no, the Mary Shelley reference is no accident) who reaches too far and through mere humanity becomes a monster rather than a hero of mankind is the culprit and the Miltonian figure at its center.

Like much popular fiction of the era the villain is no Fu Manchu or Bond villain, but a flawed superman of sorts, a figure both ultimately admired and feared, and in the end both he and his creation Number 87, the Bat, suffer exile rather than destruction more on the model of Nemo or Robur than the less noble villains to come.

Phillpotts is hardly hard-boiled or pared down as a prose stylist, but he can write and his works, while dated, are often still quite good reads. This brief scene when our narrator first spies the creature for himself is a good example.

Revelations, horrors, and terrors are to come before Granger and his friends find the remarkable solution to what the Bat is and who lies behind it much less why. It is admittedly old fashioned, but not bad for that. Certainly not to everyone’s taste, but well worth taking the time to find (easy in e-book edition if not hard copy).

Splendid blood and thunder that.

Tue 4 May 2021

ROBERT J. RANDISI – Alone with the Dead. Joe Keough #1. St Martin’s, hardcover, 1995. Leisure Books, paperback, 1999. Perfect Crime, trade paperback, 2014.

I think somebody told me this will be a series, but I’m not sure. I’ve been neither a booster nor a buster of Randisi’s books. I think he’s a pretty good writer, but I also think he gets a bit sloppy sometimes with his plots and background, and has yet to write the book he could write. Could this be it?

Joe Keough is a NYC detective, banished to a Brooklyn precinct because he lost his temper at the wrong time. He catches a case involving a rape and murder of a young girl, similar to a series of killings by a killer nicknamed “The Lover”. Joe doesn’t think it’s the same killer, but his superiors do, and overrule him. Subsequent murders convince Joe he’s right, but no one wants to look for a second serial killer but him.

Well, I still don’t think he’s written the best book he can write, but this one isn’t bad at all. Randisi is a thoroughly competent storyteller in terms of pacing and action, and he moves this one right along. It isn’t padded, and that’s a real plus – I’ve read a number of books this year with no more story that were 150 pages longer. And it’s a type of story I like, the one-good-man-against-the-system kind.

So why am I not giving it a higher rating? Keeping in mind that the grade I gave it is better than average, it’s not higher yet because his prose is workmanlike but not exceptional, and there were no characters that I thought had any depth beyond the ordinary. It’s “just†an entertaining, well-told story.

There should be more such.

Editorial Comment: Barry graded this one a “happy face smiley plus.” I’m not sure exactly what that means, but as he explains in the review, it’s somewhere above average.

The Joe Keough series —

1. Alone With the Dead (1995)

2. In the Shadow of the Arch (1997)

3. Blood on the Arch (2000)

4. East of the Arch (2002)

5. Arch Angels (2004)

… so yes, Barry was right. This book was the first in a series.

Mon 3 May 2021

RAYMOND J. HEALY & J. FRANCIS McCOMAS, Editors – Famous Science-Fiction Stories: Adventures in Time And Space. The Modern Library G-31; hardcover, 1957, xvi + 997 pages. First published as Adventures in Time in Space, Random House, hardcover, 1946. Bantam F3102, paperback, 1966, as Adventures in Time and Space (contains only 8 stories). Ballantine, paperback, 1975, also as Adventures in Time and Space.

Part 6 can be found here.

ROBERT A. HEINLEIN “The Roads Must Roll.†Novelette. A “Future History†story. Heinlein foresaw the present automobile traffic problem and proposed moving cross-country strips as a solution. The actual plot suffers in comparison to the details of the economic and sociological consequences. (3)

Update: First published in Astounding Science-Fiction, June 1940. First collected in The Man Who Sold the Moon (Shasta, hardcover, 1950). Also collected in The Past Through Tomorrow (Putnam, hardcover, 1967). Reprinted many times. Awarded a Retro Hugo as best novelette in 2016 for works published in 1940.

A. E. van VOGT “Asylum.†Short novel. Earth is pictured as a sanctuary maintained for mankind by beings with much bigger IQ’s. Two aliens with a need for fresh blood land and involve reporter William Leigh in their conflict with Earth’s guardians. This preliminary involvement is interesting, but although van Vogt does have a great knack for telling a story, the ending degenerates rapidly into confusion on a galactic scale. (3½)

Update: First published in Astounding Science-Fiction, May 1942. First collected in Away and Beyond (Pellegrini & Cudahy, hardcover, 1952). Reprinted in The Great Science Fiction Stories Volume 4, 1942, edited by Isaac Asimov & Martin H. Greenberg (Daw #405, paperback original, October 1980), among others.

LEWIS PADGETT “The Twonky.†Short story. A strange invention disguised as a radio console destroys initiative then life if uncooperative. Better than Padgett’s more humorous stories in this volume. (4)

Update: First published in Astounding Science Fiction, September 1942. Lewis Padgett was a pen name used by the prolific husband-and-wife team Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore. First collected in A Gnome There Was (Simon & Shuster, hardcover, 1950). Reprinted in The Great Science Fiction Stories Volume 4, 1942, edited by Isaac Asimov & Martin H. Greenberg (Daw #405, paperback original, October 1980), among others. When adapted to the film of the same name (United Artists, 1953, written and directed by Arch Oboler), the radio in the original story was updated to a television set.

TO BE CONTINUED.…

Mon 3 May 2021

(Give Me That) OLD-TIME DETECTION. Autumn 2020/Winter 2021. Issue #55. Editor: Arthur Vidro. Old-Time Detection Special Interest Group of American Mensa, Ltd. 36 pages (including covers). Cover image: The Radfords’ Who Killed Dick Whittington?

As is his usual wont, in this latest edition of Old-Time Detection Arthur Vidro has once again delivered a valuable compendium of information about classic detective fiction, resurrecting long-forgotten pieces as well as showcasing up-to-date commentary about the genre.

When, in 1951, Howard Haycraft and Ellery Queen (the editor) got together to compile a list of what they considered to be a “Definitive Library of Detective-Crime-Mystery Fiction,” they probably had no idea that their compilation (commonly called the “Haycraft-Queen Cornerstones”) would still be worth consulting seventy years later. One of their choices for the list is Clayton Rawson’s locked room classic Death from a Top Hat (1938), which receives Les Blatt’s scrutiny. Another “cornerstone” is Somerset Maugham’s Ashenden (1928), which Michael Dirda, in contrast to the usual consensus opinion, does not regard as “the first modern espionage novel.”

Two now largely forgotten detective fiction novelists worth spotlighting are the married writing team of E. and M. A. Radford; they receive their due attention in Nigel Moss’s essay, which sadly notes that despite a long writing career “the U.S. market eluded them.” Moss also highlights the play, that rare theatrical bird, an honest-to-goodness whodunnit, derived from the Radfords’ sixth novel, Who Killed Dick Whittington? (1947).

While he was still living, impossible crime expert Edward D. Hoch turned his attention to Agatha Christie’s short fiction and found most of it praiseworthy: “If the short stories often are not the equal of the best of her novels, they still sparkle on occasion with her vitality and ingenuity, reminding us anew of the pleasure of a well-crafted tale.”

Dr. John Curran, the world’s foremost expert on all things Christie, has nice things to say about Mark Aldridge’s Poirot: The Greatest Detective in the World, in his opinion a “must-have book for the shelves of all fans of the little Belgian and his gifted creator.” Curran also includes little-known facts about Agatha, only a few of which yours truly was aware.

Continuing with the Christie theme is a talk by Leslie Budewitz aptly entitled “The Continued Influence of Agatha Christie”; “she was,” says Budewitz, “first and foremost a tremendous storyteller.”

Then come a couple of apposite reviews, both by Jay Strafford: Sophie Hannah’s The Killings at Kingfisher Hill (2020), starring Hercule Poirot; and Andrew Wilson’s I Saw Him Die (2020), the fourth in a series of novels making the most of that Queenian fictional trope of featuring a detective fiction writer as, well, an amateur detective.

The center piece of this issue of OTD, both figuratively and literally, is Stuart Palmer’s entertaining story “Fingerprints Don’t Lie” (1947), in which Hildegarde Withers, sans Inspector Piper, solves a knotty murder in Las Vegas.

Continuing with Charles Shibuk’s series of paperback reprints from the ’70s (at the time a noteworthy and welcome trend for classic mystery buffs), he highlights works by Nicholas Blake (Mystery*File here), Charity Blackstock (Mystery*File here), John Dickson Carr (of course!; Mystery*File here ), Agatha Christie (also of course!; Mystery*File here), Raymond Chandler (ditto; Mystery*File here), Henry Kane (Mystery*File here), Patricia Moyes (Mystery*File here), Ellery Queen (Mystery*File here), Dorothy L. Sayers (Mystery*File here), Julian Symons (Mystery*File here), Josephine Tey (Mystery*File here), and editor Francis M. Nevins’s (Mystery*File here) nonfictional The Mystery Writer’s Art, “obviously the logical successor to Howard Haycraft’s The Art of the Mystery Story (1946) . . .”

Several pages of contemporary reviews of (mostly) classic mysteries follow: Jon L. Breen about Robert Barnard’s School for Murder (1983/4) and Evan Hunter’s “factional” Lizzie (1984); Harv Tudorri about Ed Hoch’s Challenge the Impossible (2018); Ruth Ordivar about Erle Stanley Gardner’s The Case of the Angry Mourner (1951); and two reviews from Arthur Vidro about Barbara D’Amato’s The Hands of Healing Murder (1980) and John Ball’s In the Heat of the Night (1965): “with maturer re-reading, I am dazzled . . .”

The issue wraps up with letters from the readers and a befitting puzzle about Agatha Christie.

All in all, Issue 55 is definitely worth adding to your collection.

If you’d like to subscribe to Old-Time Detection:

Published three times a year: spring, summer, and autumn. – Sample copy: $6.00 in U.S.; $10.00 anywhere else. – One-year U.S.: $18.00 ($15.00 for Mensans). – One-year overseas: $40.00 (or 25 pounds sterling or 30 euros). – Payment: Checks payable to Arthur Vidro, or cash from any nation, or U.S. postage stamps or PayPal. – Mailing address: Arthur Vidro, editor, Old-Time Detection, 2 Ellery Street, Claremont, New Hampshire 03743.

Web address: vidro@myfairpoint.net

Sun 2 May 2021

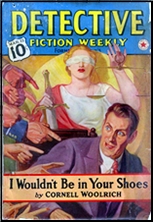

â— CORNELL WOOLRICH “I Wouldn’t be in Your Shoes.” Novelette. First published in Detective Fiction Weekly, 12 March 1938. Collected in I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes (Lippincott, hardcover, 1943), as by William Irish. Reprinted many times.

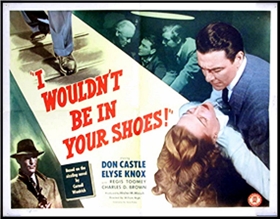

◠I WOULDN’T BE IN YOUR SHOES. Monogram, 1948. Don Castle, Elyse Knox, Regis Toomey, and Robert Lowell. Screenplay by Steve Fisher. Produced by Walter Mirisch. Directed by William Nigh.

At his worst, Woolrich could be wordy, verbose, prolix, repetitive, redundant, tiring and tedious. He could take a metaphor, strap it to the rack, and stretch it till the reader screamed for mercy. But at his best, he could wring poetry out of plot twists and make the pages sing with strange, melancholy music.

This is Woolrich at his best.

Tom Quinn starts out on a hot August night as a working stiff, married, and living on the ragged edge of poverty. By the story’s end, it will be Christmas, and he’ll sit on Death Row, framed by circumstances that could only occur in Woolrich’s dark Universe. It begins with him throwing his shoes out the window at noisy cats, builds as the shoes disappear and are mysteriously returned, then twists when he finds money on the street — money taken in a robbery-and-murder committed by someone wearing his shoes. Even his wife begins to doubt his innocence.

Whereupon Woolrich picks up a familiar theme: The Cop who pinched him begins to doubt his guilt and sets out to find the real killer, a feat achieved with fast-moving prose and a bit of genuine pathos. So Tom is free again. But fate and Woolrich have one last surprise for him….

In 1948, a producer named Walter Mirisch at Monogram foresaw the end of B-Movies as second-features and began the lengthy and sporadic process of transforming the runty little studio into the less-runty Allied Artists. Mirisch went on to things like West Side Story, Allied Artists gave us Cabaret, but in the meantime, there were still a lot of B’s to churn out, and I Wouldn’t Be in Your Shoes was one of them.

The thing is, Shoes shows some of the extra care and attention of a producer and studio aiming just a little bit higher. Don Castle and Elyse Knox take the leads as married dancers whose careers have stalled out — not unlike the careers of Castle and Knox themselves — and when he finds the money, they react believably. Screenwriter Steve Fisher wisely keeps in as many of the characters and as much of the Woolrich dialogue as the budget will allow, and he even rings in a familiar twist of his own to skew things a bit more.

What impressed me most about this, though, was the acting. Everyone involved, down to Second Detective, sounds convincing. And Robert Lowell (who he?) makes a lasting impression as the unlucky guy ultimately tracked down by gumshoe Regis Toomey.

Don’t get me wrong. This is still a B-Movie programmer, with most of the faults attendant on that art form. But it’s interesting and entertaining to see everyone giving it so much.

Sat 1 May 2021

After completing his first three novels as by A.A. Fair about the PI team of Bertha Cool and Donald Lam — actually his first four novels, with THE KNIFE SLIPPED remaining unpublished until more than forty years after his death — Erle Stanley Gardner felt the need to reconfigure his odd couple. This is why, between GOLD COMES IN BRICKS (1940) and the next book in the series, Bertha was hit simultaneously with the flu and pneumonia and spent quite a bit of time in a Salt Lake City sanitarium where she lost about 100 pounds, although at between 150 and 160 she’d hardly be mistaken for a sylph.

At the beginning of SPILL THE JACKPOT! (1941), which takes place and was apparently written shortly after the 1940 presidential election which gave FDR his third term, a not yet reconfigured Donald is about to take her home by plane, with a brief stopover in Las Vegas so that he can confer with the firm’s newest client. Ad agency owner Arthur Whitewell has retained Bertha’s outfit to locate the young woman his son Philip was about to marry, who vanished shortly before the wedding after receiving a mysterious letter from a woman in Vegas named Helen Framley.

Donald finds Helen’s apartment quickly enough but she isn’t home and he decides to kill a little time at a nearby casino. In something of a Keeler Koinkydink, the woman playing the slot machine next to him is, you guessed it, Helen — and both she and the tough guy on the other side of her have gimmicked their machines so that they produce one jackpot after another. An attendant on the watch for just such trickery accuses the two of them and Donald too.

The tough guy and Helen manage to escape, but Donald is knocked down and arrested. He clears himself by proving his identity and agrees not to sue the casino in return for some co-operation. The attendant who socked Donald, a punch-drunk ex-boxer who if there had been a movie based on this book would probably have been played by Mike Mazurki, takes a huge liking to the little guy and offers to teach him some tricks of the pugilism trade, an offer which, as we’ll see, opens the door to Donald’s reconfiguration.

That evening Donald boards the night train to Los Angeles, but in the wee hours he’s hauled out of his sleeping compartment by the police and taken back forcibly to Las Vegas where Helen’s accomplice has been found shot to death in her apartment. Donald was at the railroad station at the time, waiting for his train, but can’t prove it, and soon he and Helen and the ex-pug go on the run.

The plot this time is less involuted than most of Gardner’s, and suffers here and there from careless plotting; Donald, for example, locates the vanished bride-to-be only because she’s going by a name no rational person in her position would have used. Without slowing the pace, Gardner punctuates the novel with side excursions, in the first of which we learn perhaps more than we want to know about the gimmicking of slot machines.

But the later excursions are much more rewarding. I especially liked the sequence where Donald and Helen and the ex-pug Louie Hazen, on the run from the police, camp out on the desert as their creator loved to do most of his life. “There has never been anything quite as soul-satisfying, quite as filled with the promise of life, as the smell of coffee out in the open when the fresh air has done its work and you realize that you’re ravenously hungry.â€

I also enjoyed the later scenes where the three hole up in a one-cabin wilderness motel — with how many bedrooms remains murky — and Louie teaches Donald to be a boxer. Gardner, you may remember, fought in a number of unlicensed matches in his salad days. At the climax Donald finds a confession letter from the murderer (who actually killed in self-defense), lets that person go free and frames one of the other characters who is much more of (forgive me, all you critters who bear the noble name of Bufo bufo) a toad, although the frame would fall flat on its kiester unless Donald and the dead guy happen to be of the same blood type. I challenge anyone to find an ending so cynical in a Perry Mason novel.

From its title you might guess that gambling would also figure prominently in DOUBLE OR QUITS (1941). But the first word in the title of the fifth (or, if you count THE KNIFE SLIPPED, the sixth) Cool & Lam exploit actually refers to that old standby of crime fiction, double indemnity — and to the legal difference between accidental death, which doesn’t pay double the face amount of a life insurance policy, and death by accidental means, which does.

On a fishing excursion Donald and Bertha meet a prosperous doctor who immediately hires the firm to investigate the theft of his wife’s jewels from a wall safe in his study to which he alone knew the combination — or so he thought — and the simultaneous disappearance of his wife’s secretary.

Donald spends that evening at the doctor’s house meeting his family, which includes a niece and nephew of the wife who are living with their aunt and uncle. Later the doctor goes out to make a couple of house calls, leaving Donald in his study. Close to midnight, during a Santa Ana windstorm, Donald finds him dead in his garage, apparently a victim of carbon monoxide poisoning while tinkering with his car, whose motor is running and whose glove compartment contains a valuable ring belonging to his wife plus the cases for all the stolen jewelry.

Unfortunately for the widow, who’s the beneficiary of his life insurance policy, if the situation is what it seems his death was accidental but not by accidental means. Result: no double indemnity.

The complications keep piling up along with suspicious characters like the vanished secretary’s roommate, the niece’s ex-husband and her lawyer, a sinister chauffeur and a suave oil speculator. Eventually Donald sets up a test in the garage, trying to establish that the Santa Ana winds might have slammed down the overhead door, which would constitute accidental means and require the insurance company to pay double.

But everything goes wrong and Donald winds up in a fistfight with the insurance adjuster in which, thanks to Louie Hazen’s training in SPILL THE JACKPOT!, he acquits himself handily. He also makes out very well in his employment situation, literally quitting the firm in mid-case until Bertha promotes him to full partner.

Back on the job he finds another body, this one clearly a murder victim, strangled with string from a girdle tightened around the neck by, I am not making this up, a potato masher. DOUBLE OR QUITS earned a rave from Barzun & Taylor in A CATALOGUE OF CRIME (2nd ed. 1989): “One of the best of the A.A. Fair stories. It is witty, reasonably simple, and brilliantly told….â€

Personally I found it no more witty or brilliantly narrated than any other book in the long-running series, with a plot not simple but all too complicated, characters with confusingly similar names (would you believe Timken, Timley and Harmley?), and at least one crucial fact — that the two doctors in the cast live within walking distance of each other — kept concealed from us until too late. But it’s readable enough and plays at least partially fair, so let’s give it one thumb up.

Between DOUBLE OR QUITS and the next C&L novel, Pearl Harbor was attacked, the U.S. went to war, and every mystery writer with a male series character below middle age had to face the question Why is my man not in uniform? Gardner didn’t have to worry about Perry Mason, whose age was never given and whom most readers probably thought of as in his forties, but with Donald Lam, who had been established as in his late twenties, it was a different story.

OWLS DON’T BLINK (1942), which takes place a few months after Pearl Harbor, opens in medias res and in the middle of the night with Donald in New Orleans trying to track down yet another vanished woman, whose apartment in the French Quarter he’s rented for a week.

In the morning Bertha arrives in town by train along with the firm’s latest client, a New York lawyer who had hired these Los Angeles PIs to find a vanished woman in New Orleans but refuses to explain why he wants to find her. Donald locates the woman easily enough but soon discovers that she was using another woman’s name

and winds up in the middle of a Machiavellian legal maneuver to invalidate a wealthy Californian’s divorce on the ground that it wasn’t his estranged wife but another woman who was served with process.

Then the lawyer who dreamed up the scheme is shot to death in the present apartment of the woman Donald was looking for, and the trail of the woman she was impersonating leads him first to Shreveport and then back to L.A.

The plot has a little bit of everything: scams within scams, gun switching, legal issues, a consignment of silk stockings that exists only in Donald’s imagination, ju-jitsu, and a love song to that classic New Orleans dish, oysters Rockefeller. “The shells are placed in rock salt. There’s a little touch of garlic and a special sauce….And then they’re baked, right in their shells.â€

It’s such a rich assortment of ingredients that few will object to the Keeler Koinkydink that everything hinges on the two women in the dead man’s life living across an apartment-house corridor from each other.

During the middle stretches Donald discovers that Bertha has surreptitiously started a second business and wangled a contract to build military housing, apparently to keep him from being drafted on the ground that he works in a defense industry, and angrily retaliates, after solving the case, by enlisting in the Navy.

That decision brings the first sequence of C&L adventures to an abrupt end. How Gardner managed to continue the series while his male hero was in Navy whites must be saved till later this year.

Fri 30 Apr 2021

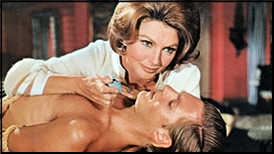

DEADLIER THAN THE MALE. Rank, UK, 1966. Universal, US, 1967. Richard Johnson (Hugh Drummond), Elke Sommer, Sylva Koscina, Nigel Green, Suzanna Leigh, Steve Carlson. Screenwriters: Jimmy Sangster, David Osborn) & Liz Charles-Williams, based on a original story by Jimmy Sangster and the character Bulldog Drummond created by Herman C. McNeile (as Sapper) & Gerard Fairlie. Directed by Ralph Thomas.

By the late 1960s, almost everyone was cashing in on the wildly successful Bond films and seeing if they could make their own without breaking the international copyright laws. This splurge of spy movies gave us the two Derek Flint films with James Coburn, the four Matt Helm films, questionably starring Dean Martin, and – closer to home – the so-called ‘Euro-spy’ films. These were badly-dubbed Italian and French films which featured a Bond-like character.

Here in Britain, we also had the Harry Palmer films, The Quiller Memorandum, Hot Enough for June and Modesty Blaise, along with comedies like Carry On Spying and that one with Morcambe & Wise.

So it was only expected that some bright spark would dust off the old Bulldog Drummond adventure novels by 1920s writer ‘Sapper’ which were partly responsible for Bond in the first place. The original character is considered to be a racist bigot now, but he was more or less Bertie Wooster with a penchant for brutal justice and initially went up against criminal mastermind Carl Peterson.

This film, however, strips Drummond of his nick-name, military rank, character, backstory, supporting cast and storylines and makes him a smooth, wryly-amusing insurance investigator with a Rolls Royce and a passion for karate. Richard Johnson would always be a respected actor and is perfectly likeable here as Drummond, but he was clearly cast because he bears a passing resemblance to Sean Connery.

That’s no bad thing, of course. I would’ve cast someone who looked like Connery too (I wouldn’t, however, have cast Connery’s brother, as Italian director Alberto De Martino did that same year).

I had big hopes for this film, not least because it managed to spawn a sequel, but mainly because I had seen so much love for it on the internet.

First, the good: there’s the two glamorous female assassins, Irma and Penelope, played by Elke Sommer and Sylva Koscina. There’s an outrageously Avengers-like scene near the beginning in which they emerge from the ocean, clad in bikinis and armed with spear-guns, and kill a sunbather. There’s a cigar which fires bullets into whoever smokes it. There is the excellent Nigel Green.

Also, Leonard Rossiter (whose ability and work, of course, there isn’t a superlative strong enough to describe) dies in another Avengers-like scene in which our pair of saucy slaughterers paralyses him with a mysterious spy-fi drug and send him tumbling off the balcony of his fifteen-storey apartment building.

There’s also a great bit where Drummond meets his old army friend, the crime boss Boxer, who is lying low in a tropically-themed flat after faking his own death. It’s one of those instances in which the character seems to live beyond the confines of the scene he’s in.

Finally, there’s the climax, where Drummond and his nemesis creep around a life-size chess board in a duel to the death. Again, very Avengers. So, how come I don’t like the film as a whole?

Well, the plot is dull and unimaginative. It’s all about a company named Phoenecian Oil and a merger which one man on the board of directors, Henry Keller, opposes. A third party has offered to resolve the issue, via an undisclosed method, within six months and asks to receive a million pounds in return. Subsequently, Keller dies in a plane explosion, the merger can go ahead and this mysterious problem-solver demands payment. It is, of course, villain Carl Peterson and he wants to take his murderous solution to every corporation in the world.

Drummond is tasked with finding out what is going on. His only lead is an inch of audio tape which Keller had recorded a message, but only half of one sentence remains. It could well reveal the answer to the mystery, if Drummond can only make sense of the jumble of words.

Unfortunately for Drummond, and indeed the viewer, his American nephew Robert has come to stay with him. Now, in order to secure distribution in the states, many British films cast an American actor in a role. This is one such example. As the ‘60s was a decade obsessed with youth, perhaps it seemed like a good idea to cast one in the film. Arguably, the result isn’t a good one, as the Robert character brings next to nothing to the film and distracts from the story it is trying to tell.

The whole movie can be divided between the first half, set in London, and the second half, which moves to Northern Italy. Here, the film seems to come to a crashing halt. Drummond meets Peterson, yes, and we get to see his castle lair, but nothing really happens. It’s this half which I have always struggled with during three previous efforts to appreciate the film.

I must reiterate, however, that the film seems popular enough with other people, and is certainly better than a couple of other Bond-pastiches of the era, such as Death Is a Woman (1966) and Hot Enough for June (1964), both of which I found to be utterly unwatchable.

Despite this, I’ll check out the sequel [Some Girls Do (1969) was the second], while I’m always in the mood to watch the older Bulldog Drummond films, and indeed the books.

Rating: **