Sun 21 Mar 2021

A 1001 Midnights Review: WILKIE COLLINS – The Moonstone.

Posted by Steve under 1001 Midnights , Reviews[7] Comments

by Marcia Muller

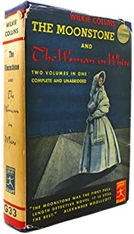

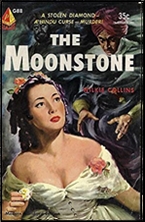

WILKIE COLLINS – The Moonstone. Tinsley, US, hardcover, 1868. Harper, US, hardcover 1868. Serialised in Charles Dickens’s magazine All the Year Round and in the US in Harper’s Weekly, circa 1868. Reprinted many times in both hardcover and soft. (The book has probably never been out of print.) Adapted many times for the stage, movies, radio, TV, comic books and (!) a podcast.

(William) Wilkie Collins was one of the most popular and accomplished writers of the nineteenth century, and The Moonstone is an early classic of the suspense genre. Like Collins’ other criminous works, it contains elements that later became staples of mystery writing: a purloined gemstone, carefully secreted clues, obtrusive red herrings, sinister Indians who lurk threateningly in the background, a blighted love affair, several shakily constructed alibis, numerous cliff-hanging scenes, and a mysterious suicide. Although complicated, the plot is well constructed and the reader’s interest seldom flags.

The yellow diamond known as the “moonstone” was stolen from an Indian religious idol by John Herncastle, a man who chose to ignore the story of bad luck following the diamond should it be removed from the possession of the worshipers of the moon god. Upon Herncastle’s death, the gem was willed to his niece, Rachel Verinder, and the young lady is about to receive it when the story opens (after a prologue and two tiresome chapters filled with background material).

The diamond disappears, of course, on the night Rachel is presented it by solicitor Franklin Blake. And when Inspector Cuff of Scotland Yard appears on the scene, some clues point to Blake, while others indicate Rachel has secreted away her own diamond for some unknown and possibly unbalanced reason.

The story proceeds, divided into two periods, respectively titled “The Loss of the Diamond” and “The Discovery of the Truth” (which in itself is divided into eight narratives), plus an epilogue. In spite of these numerous sections, each broken into various chapters narrated by different characters, the reader finds himself as determined as Cuff to learn the truth. Who are the Indians? Was this caused by the curse of the moonstone? Will Rachel find happiness? Such questions are ever in the forefront. And when the end is finally reached, all clues are tied up, all questions are answered, and — yes — Rachel does find happiness.

Collins’ other works are not nearly as well known as The Moonstone, but a number are just as engrossing and stand the test of time equally well. These include The Woman in White (1860), which seems to have been Collins’ personal favorite; and The Queen of Hearts (1859), a collection that contains the cornerstone humorous detective story “The Biter Bit.”

———

Reprinted with permission from 1001 Midnights, edited by Bill Pronzini & Marcia Muller and published by The Battered Silicon Dispatch Box, 2007. Copyright © 1986, 2007 by the Pronzini-Muller Family Trust.