Wed 22 Jul 2009

A Review by David L. Vineyard: GEORGE HOPLEY [CORNELL WOOLRICH] – Night Has a Thousand Eyes.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[9] Comments

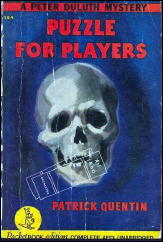

GEORGE HOPLEY – Night Has a Thousand Eyes. Farrar & Rinehart, hardcover, 1945. Reprinted as by William Irish: Dell #679, 1953. Reprinted as by Cornell Woolrich: Paperback Library 54-438, 1967. Many other reprint editions, both hardcover and soft.

Cornell Woolrich, that twisted and tortured man who haunted the novel of suspense like some Twentieth Century Poe, coined the term “line of suspense” to describe the mechanism that drives a good suspense novel.

In the simplest terms it is the element that drives the tale from one incident to the next — perhaps the killer’s motive as in The Bride Wore Black, the heroes amnesia as in Black Curtain, or here, in Woolrich’s masterpiece, the possibility of psychic powers and the inevitability of fate.

Woolrich’s novels are haunted by fate, sheer blind cruel and pointless fate. An unmarried pregnant woman on a train survives an accident and happens to be mistaken for another pregnant woman in the same car whose husband’s wealthy family has never seen her; a night’s drunk finds you facing the hot seat with no memory of what happened; a leopard escaped from an night club act cloaks the twisted mind of a killer; a sailor and a taxi dancer have only until dawn to clear him of a crime…

Fate is always having its little joke in Woolrich’s novels and stories, and in Night Has 1000 Eyes that little joke is at its most effective, and terrible.

Night opens appropriately at night. The hero is a young detective who spots an attractive young woman attempting suicide. He stops her, only to find she is desperate and frightened out of her wits.

Her wealthy father has been threatened, but this is no ordinary threat. A man claiming psychic powers has told her that her father will die at an appointed time and cannot be saved. And this psychic is never wrong.

Never.

Naturally the police take a dim view of this sort of thing, even though the psychic seemingly has asked for no money and committed no crime. But they encounter clever bunco artists all the time and they know that if they look deep enough they’ll find the game behind this one. Besides you can’t go around threatening a cities most wealthy men with blind retribution — it makes the taxpayers nervous.

Meanwhile the clock ticks and the time nears when the appointed hour will come.

And for every step forward there is one back, and still the uncanny predictions of this strange man come true.

When they finally uncover a tawdry romantic triangle involving the psychic, the victim, and the girl’s late mother they are certain they have the key — revenge and extortion. Still, they take no chances. They ring the victim with police and arrest the psychic who insists he means no harm to his old friend, and that he too will die shortly after the first man at his own appointed hour.

Now Woolrich ratchets the horror up to incredible levels. The tension is palpable and the suspense grows as each twist, each revelation comes. The psychic has predicted the man will die between the paws of a lion, and as the hour nears a lion escapes from the zoo, loose in the very area where the victim lives.

Mere coincidence, and yet …

And yet.

Ernest K. Gann coined the term “fate is the hunter” to explain why he left commercial aviation — because at some point in a pilot’s career the laws of simple math catch up with him and it becomes more likely he will crash than that he won’t. Woolrich understood the idea. Fate is a remorseless hunter, but Woolrich knows too you can’t run or hide.

Night Has a Thosand Eyes is a suspense novel and not a horror novel, but rightly has been claimed by both genres because the effect of the accumulation of events and coincidence begins to resemble something supernatural, though at each and every turn Woolrich is careful to eschew the simple explanation.

Again and again he takes the reader right up to the point of madness, and then pulls away, reveals another twist, shows us another possible path, all the while maintaining a palpable line of suspense that is almost unbearable.

Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a fairly long novel, but I have a hard time believing anyone once starting it put it down before it ended. Or slept much afterward.

And that may be where this book most resembles a horror novel and not a suspense novel, because most good suspense novels let you go when they come to the end. There is a build up to incredible tension and then a release.

Not in Night Has a Thousand Eyes.

If anything this book is more disturbing when it is over.

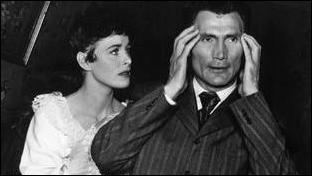

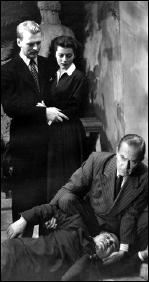

Night Has a Thousand Eyes was well filmed by John Farrow with a fine screenplay by Barré Lyndon and Jonathan Latimer, with Gail Russell perfectly cast as the fey girl, John Lund the hero, Edward G, Robinson the psychic, William Demarest a doubting cop, and Jerome Cowan the doomed victim.

It’s a fine piece of film noir, but it is only a pale shadow of the novel. I don’t know that you could translate on film the tension that Woolrich builds in print. I’m not sure you’d want to, because as I say, Night Has a Thousand Eyes doesn’t let you off the hook. Not even when you have turned the last page and laid the book aside.

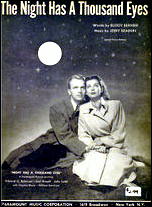

The book also inspired a popular song that warned us “The night has a thousand eyes/ and a thousand eyes can’t help but see…” recorded by Bobbie Vee, and the song from the film by John Brahin was and still is a popular jazz riff. (Follow the link to a YouTube video of the Bobby Vee version.)

That title has the ring of some ancient bit of wisdom or poetry. It has the feel of found wisdom, of something we all knew, but never put into words before this.

The night has one thousand eyes and they are watching us. We cannot run from them, we cannot escape them. Fate will not be denied, nor can any man escape his appointed time. We all will make our own appointment in Samara on time.

And perhaps it is that inevitability that gives this novel its power. We aren’t let off with easy answers, and though the solution leaves itself fully open for rational explanation there is a cold dark corner of the soul that knows that isn’t what Woolrich was telling us.

Woolrich wrote only one other as George Hopley, the majority of his work appearing as by Woolrich or William Irish. Many of his novels deserve to be read and reread, they are masterpieces of suspense, and despite his tendency to overheated prose even the least of them are worth rereading. But Night Has a Thousand Eyes is a special case.

Even among his output of taut and often disturbing novels, this one is a masterpiece. This is the one unforgettable novel in his repertoire.

Read it and you will never forget it.

But don’t read it before bedtime.

Not if you ever want a good night’s sleep again.