A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

ELLERY QUEEN, Editor – Masterpieces of Mystery: The Supersleuths. Davis Publications, hardcover, 1976.

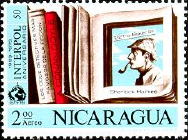

Back in the early 1970s, the country of Nicaragua asked Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine (EQMM) “to set up a poll to establish the dozen greatest detectives of all time” in anticipation of that nation’s issuing a commemorative set of twelve postage stamps to celebrate the 50th anniversary of Interpol. This book is a result — or, perhaps, a by-product of that request.

EQMM conducted three polls of mystery critics and editors, professional mystery writers, and mystery readers. It was from the last group that an unexpected (to Ellery Queen) result came:

“Only one fictional detective was voted for unanimously by mystery critics, mystery editors, and mystery writers — not surprisingly, Sherlock Holmes. But, surprisingly, the vote for Sherlock Holmes by mystery readers was not unanimous: no less than 64 readers out of 1,090 failed to rank Holmes as one of the 12 best and greatest. Surprising, indeed. (Surprising? Incredible!)”

Here are the poll results, in order of popularity:

1-Sherlock Holmes 2-Hercule Poirot 3-Ellery Queen 4-Nero Wolfe 5-Perry Mason 6-Charlie Chan 7-Inspector Maigret 8-C. Auguste Dupin 9-Sam Spade 10-Father Brown 11-Lord Peter Wimsey 12-Philip Marlowe 13-Dr. Gideon Fell 14-Lew Archer 15-Albert Campion 16-George Gideon 17-Miss Jane Marple 18-Philo Vance 19-The Saint (Simon Templar) 20-Roderick Alleyn 21-Luis Mendoza 22-Sir Henry Merrivale 23-Mike Hammer 24-James Bond 25-Sergeant Cuff 26-Inspector Roger West

“This anthology … contains stories by 14 of the 15 top vote-getters in the three combined polls — 14 of the 15 most famous and most popular detective heroes of fiction.”

Ellery Queen includes a note: “Why Charlie Chan Does Not Appear in the Volume.” Can you guess why?

Each story in this volume is introduced by a short biographical paragraph and a cameo photograph of the author(s).

CONTENTS:

1. “The Adventure of the Abbey Grange” (1904) by A. Conan Doyle (1859-1930). Supersleuth: Sherlock Holmes.

… our thoughts were entirely absorbed by the terrible object which lay upon the tiger-skin hearthrug in front of the fire. It was the body of a tall, well-made man, about forty years of age. He lay upon his back, his face upturned, with his white teeth grinning through his short, black beard.

Comment: When a rich but sadistic man is apparently murdered by a gang of burglars, Holmes and Watson are summoned; but the case quickly grows more complex. The solution lies in the presence of three wine glasses and a frayed bell-rope. Holmes remarks to Watson at one point: “Once or twice in my career I feel that I have done more real harm by my discovery of the criminal than ever he had done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather play tricks with the law of England than with my own conscience.” Filmed for TV in 1986 with Jeremy Brett.

2. “The Dream” (1937) by Agatha Christie (1890-1976). Supersleuth: Hercule Poirot.

“My laundress,” said Poirot, “was very important. That miserable woman who ruins my collars was, for the first time in her life, useful to somebody.”

Comment: When a man who dreams that he commits suicide is found dead in a watched room, only Poirot suspects murder. “Motive and opportunity are not enough …. There must also be the criminal temperament.” Filmed for TV in 1989 with David Suchet.

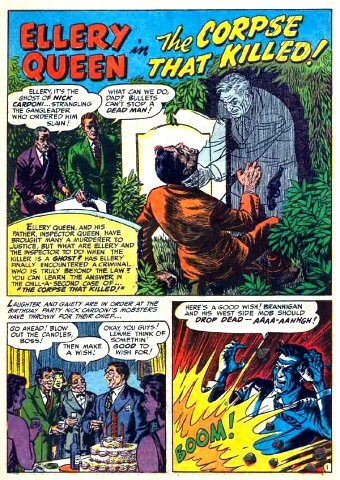

3. “The Case Against Carroll” (1958) by Ellery Queen (1905-1971; 1905-1982). Supersleuth: Ellery Queen.

“The Fancy Dan who weaves an elaborate shroud for somebody else more often than not winds up occupying it himself. The clever boys trip over their own cleverness. There’s a complex pattern here, and it’s getting more tangled by the hour.”

Comment: The case against Carroll — accused of murdering a law firm partner — seems airtight; the noose tightens when someone who can support his alibi is also murdered. This story is a clever variation on alibi-breaking and is perhaps the penultimate example of that theme. Notice how the narrative’s focus shifts from Carroll at the start to Ellery at the end.

4. “The Zero Clue” (1953) by Rex Stout (1886-1975). Supersleuth: Nero Wolfe (with an able — but unwelcome — assist from Archie Goodwin).

That was a funny thing. I’m strong on hunches, and I’ve had some beauts during the years I’ve been with Wolfe; but that day there wasn’t the slightest glimmer of something impending.

Comment: A mathematical genius is murdered and Archie unwittingly visits the crime scene, causing Inspector Cramer and a horde of policemen to invade Wolfe’s inner sanctum ( “The biggest assortment of homicide employees I had ever gazed on extended from wall to wall in the rear ….”) The dying clue involves eight pencils and a broken eraser, and the solution is found in Hindu mathematics — go figure!

5. “The Case of the Crimson Kiss” (1948) by Erle Stanley Gardner (1889-1970). Supersleuth: Perry Mason (with Della Street and Paul Drake).

“Ordinarily I’d spar for time, but in this case I’m afraid time is our enemy, Della. We’re going to have to walk into court with all the assurance in the world and pull a very large rabbit out of a very small hat.”

Comment: “… Carver L. Clements, wealthy playboy, yachtsman, broker, gambler for high stakes, was dead.” And good riddance, too. But why is Fay Allison, who never even met the deceased, on trial for his murder — especially when there are better suspects around like, say, Perry Mason and Della Street? Talk about your kiss of death! Filmed for TV in 1957 with Raymond Burr.

6. “Inspector Maigret Pursues” (1961) by Georges Simenon (1903-1989). Supersleuth: Inspector Maigret.

Had the police one single clue? Nothing. Not one piece of evidence. A man killed during the night in the Bois de Boulogne. No weapon is found. No prints.

Comment: Slogging police work for Maigret and his detectives through the freezing streets and stuffy bars of wintertime Paris. “He didn’t know yet that this dreadful trail was to become a classic, and that for years the older generation of detectives would recount the details to new colleagues.” Yet Maigret came to view it differently: “As things turned out, this case was to be referred to at Headquarters as the one perhaps most characteristically Maigret; but when they spoke of it in his hearing, he had a curious way of turning his head away with a groan.”

7. “The Purloined Letter” (1844) by Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849). Supersleuth: C. Auguste Dupin.

“… I have received personal information, from a very high quarter, that a certain document of the last importance has been purloined from the royal apartments. The individual who purloined it is known — this beyond a doubt; he was seen to take it. It is known, also, that it still remains in his possession.”

Comment: The world’s first armchair detective chain smokes his way to a logical solution to a non-violent crime.

8. “Too Many Have Lived” (1932) by Dashiell Hammett (1894-1961). Supersleuth: Sam Spade.

“Who is this Eli Haven?” “He’s a bad egg. He doesn’t do anything. Writes poetry or something.”

Comment: The world’s first popular gumshoe chain-smokes his way to a logical solution to a very violent crime.

9. “The Man in the Passage” (1913) by Gilbert K. Chesterton (1874-1936). Supersleuth: Father Brown.

The three men looked down, and in one of them at least the life died in that late light of afternoon. It ran along the passage like a path of gold, and in the midst of it Aurora Rome lay lustrous in her robes of green and gold, with her dead face turned upwards.

Comment: Actress Aurora Rome is murdered in her theatre dressing room amidst a group of admirers — and one nondescript Catholic priest. Considering that everyone but the clergyman had experienced amorous impulses exceeding adoration towards her, why would anybody want to kill her? In a courtroom finale, Father Brown clarifies it all, you could say, by holding up a mirror to human nature. (Defense counsel is named Patrick Butler — just a coincidence?)

10. “The Footsteps That Ran” (1928) by Dorothy L. Sayers (1893-1957). Supersleuth: Lord Peter Wimsey (with Bunter).

“No use playing your bally-fool-with-an-eyeglass tricks on me, Wimsey. I’m up to them.”

Comment: Lord Peter Wimsey-cally solves it when a woman is murdered right over his head, one floor up. The assailant has apparently taken flight with the weapon, but the killer’s goose is cooked when Wimsey gets the bird.

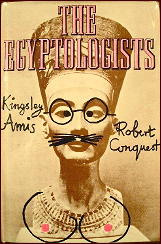

11. “The Pencil” (1959; published posthumously) by Raymond Chandler (1888-1959). Supersleuth: Philip Marlowe.

I had my pipe lit and going well. I frowned down at the one-grand note. I could use it very nicely. My checking account could kiss the sidewalk without stooping.

Comment: Marlowe is hired by “an ex-hood, used to be a troubleshooter for the Outfit, the Syndicate, the big mob, or whatever name you want to use for it.” As he wisecracks his way through the case, he receives — by Special Delivery, no less — the … pencil!

12. “The Proverbial Murder” (1943) by John Dickson Carr (1906-1977). Supersleuth: Dr. Gideon Fell .

“You see,” [Dr. Fell] said, “this crime is very much more ingenious than it looks. A certain person who is listening to me now has created something of an artistic masterpiece.”

Comment: A simple case for Gideon Fell — simple, that is, if, like him, you can correctly connect up the disturbed window curtain, the disappearing stuffed wildcat, dried moss that’s gone missing, and a gun that couldn’t possibly have fired the fatal bullet but did. Archons of Athens!

13. “Midnight Blue” (1960) by Ross Macdonald (1915-1983). Supersleuth: Lew Archer.

Her hair was in curlers. She looked like a blonde Gorgon. I smiled up at her, the way the Greek whose name I don’t remember must have smiled.

Comment: Archer goes target shooting and stumbles across the body of a high school senior, her neck in a noose. Did the crack-brained hobo do it, or the highway patrol dispatcher; or was it the grieving father, or maybe the restaurant cook (a proven killer), or the philandering teacher or his estranged wife? The motive is just about the oldest one in the book, as Sam Hawthorne has been known to say.

14. “One Morning They’ll Hang Him” (1950) by Margery Allingham (1904-1966). Supersleuth: Albert Campion.

“It’s not a great matter — just one of those stupid little snags which has some perfectly obvious explanation. Once it’s settled the whole case is open-and-shut … It’s just one of those ordinary, rather depressing little stories which most murder cases are. There’s practically no mystery, no chase — nothing but a wretched liittle tragedy.”

Comment: On the contrary, Inspector Kenny, the “perfectly obvious explanation” you hope for is an illusion, as Mr. Campion goes on to prove. A shell-shocked war veteran is the prime suspect in the murder of his hot-tempered aunt, but the weapon is missing (it is, in fact, anything but sedentary). Once the killer and the gun are reunited, only then can you say “the whole case is open-and-shut.