FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

After completing five novels about William Crane, Latimer took a break from crime fiction and made an attempt to go mainstream. The result was DARK MEMORY (1940), his last hardcover book to appear in the U.S. for fifteen years, offering us what John Fraser in a Mystery*File essay many years ago called “a Hemingwayesque African safari novel†with “no mystery/thriller/crime fiction aspects to it at all….â€

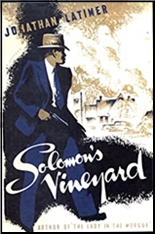

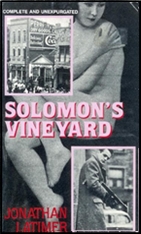

Then Latimer returned to the PI genre, but carelessly and in great haste and with trimmings American publishers seem to have found repulsive. SOLOMON’S VINEYARD (1941) was issued and apparently sold quite well in Blitzkrieg-battered England but on this side of the pond was available for decades only under a different title and in bowdlerized form. I am lucky enough to have copies of both the censored and the uncensored versions and therefore am in a position to compare them in detail.

First however I need to describe what happens in VINEYARD, in which Latimer’s obvious goal was to incorporate as many elements from Dashiell Hammett as was humanly possible. Our first-person narrator, St. Louis-based PI Karl Craven, is both fat and tough like Hammett’s Continental Op, although Craven tells us flat out that he cares about nothing but eating, boozing, fighting and sex, while the Op’s only passion is detective work.

If VINEYARD had made it to the movies he might have been played very effectively by William Conrad as he looked when he portrayed one of the killers in THE KILLERS (1946). Paulton, the Missouri city at which Craven steps off the train as the book begins, is clearly modeled on Poisonville from RED HARVEST, complete with ubiquitous gangsters and corrupt officials and even a sloppy cop in the first chapter.

Several characters, such as fat Chief Piper and the good-hearted hooker Carmel Todd and her tubercular half-brother, come straight out of HARVEST where their names were Chief Noonan (another fat man), Dinah Brand and Whisper Thaler. Events in both novels are (dare I say it?) triggered by the killing of the son of the town’s richest man (Donald Willsson in HARVEST, Caryle Waterman in VINEYARD), although the latter’s death is not a deliberate murder. Like the Op in HARVEST, Craven spends a good part of VINEYARD manipulating the gangster factions in the town so that they wind up killing each other off.

But Latimer doesn’t neglect the other Hammett novels. Deeply involved in the sleazy affairs of the community is a bizarre religious cult such as the one the Op tackled in THE DAIN CURSE, and Craven’s mission in Paulton is to get a young woman out of the Temple’s clutches just as the Op tried to do in DAIN. He was preceded on this mission by his partner, who was shot to death not long before Craven’s arrival, and as we all know from THE MALTESE FALCON, when a PI’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it.

It’s not clear whether Latimer borrowed anything from THE GLASS KEY, but Craven does get punched around several times although, unlike Ned Beaumont, he gives back at least as many blows as he receives. From THE THIN MAN nothing seems to have been lifted, perhaps because Latimer had taken his fill from that final Hammett novel in RED GARDENIAS.

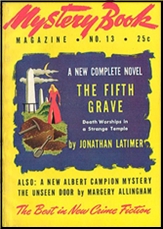

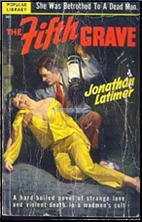

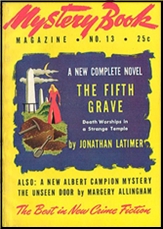

Soon after the war a modified version of VINEYARD was published in Mystery Book Magazine (August 1946) and, a few years later, as a paperback original (Popular Library, pb #301, 1950). Both versions had a new title, THE FIFTH GRAVE, and differed from VINEYARD in several ways, which deserve some exploring:

(1) The most defensible alteration corrects some gaffes. Three of the minor characters in VINEYARD — the hotel porter, the salesman who gets into a fight with Craven in the hotel bar, and the good-hearted whore’s half-brother — -are all named Charley. In the U.S. version the salesman is rechristened Teddy and the half-brother Donnie. (The corrupt police chief in VINEYARD is named Piper and one of the gangsters killed in a shootout is called Piper Sommes, but the American editors missed this overlap and left both names intact.)

An especially huge gaffe takes place in Chapter 15 when Craven searches the temple’s treasure vault and finds more than $50,000 in cash including, I am not making this up, thirty $600 bills. In THE FIFTH GRAVE this becomes thirty-one $500 bills. Both versions tell us that a total of $52,100 was found but if you add up the figures in VINEYARD — 25 $1,000 bills, 30 $600, 27 $200, 62 $100 — the sum total is $54,600. It seems that Latimer was writing so fast he couldn’t even get the math right. At least the American editors could add properly.

(2) The dates on the five gravestones Craven discovers in Chapter 15 of VINEYARD are given as 1937 through 1940, the year the events take place. In the U.S. version, supposedly set when the tale was published in Mystery Book, the years are updated to between 1942 and ‘46. For the same reason the poster Craven notices early in Chapter 17, advertising the Clark Gable movie SAN FRANCISCO (1936), is eliminated.

(3) Early in VINEYARD Craven sends the hotel porter for magazines, specifying: “Film Fun and some of those others with photographs of half-naked babes, and Black Mask.†In Mystery Book, whose editors weren’t interested in plugging other publications, this becomes “Movie magazines and a pulp detective.†The phrase about the half-naked babes remains untouched.

(4) But elsewhere the sexual innuendo is toned down. Compare these sentences from the first pages of the two versions:

1941: “From the way her buttocks looked under the black silk dress, I knew she’d be good in bed….She had gold-blonde hair, and curves, and breasts the size of Cuban pine-apples.â€

Mystery Book and Popular Library: “From the way she looked under the black silk dress, I knew she’d be a hot dame…. She had gold-blonde hair, and plenty of curves.â€

For a much more drastic bowdlerization, take a look at the rough-sex scene in Chapter 9. The “she†is the woman from the first paragraphs, who’s known as the Princess. Everything that was dropped when VINEYARD was published in the U.S. I’ve put in caps:

She slapped me….She hit my arms and my chest. I tried to hold her.

“HIT ME!†SHE SAID.

It was GODDAM queer….She struck my chest.

SHE SAID: “HIT ME.â€

I hit her easy on the ribs. “That’s right! That’s right!†She hit me a couple of hard blows. Her eyes were wild. She hit me a hard punch on the neck. I hit her in the belly…. She kept coming in, punching hard.

I GAVE HER ONE OVER THE KIDNEYS. SHE GRUNTED AND CLENCHED WITH ME. SHE BIT MY ARM UNTIL THE BLOOD CAME. I SLAPPED HER. SHE PUT HER KNEE IN MY GROIN. IT HURT. I LOST MY BALANCE, GRABBED FOR HER, AND WE BOTH WENT DOWN. WE ROLLED AROUND ON THE DIRTY FLOOR OF THE SHACK, BOTH PANTING…. I GOT OVER HER, HOLDING HER DOWN ON THE FLOOR…. She bit my arm again and I slugged her in the ribs. … My hand caught in the scarlet shirt. The silk tore to her navel.

“Yes,†she said.

I GOT THE IDEA. I RIPPED THE SHIRT OFF HER, SHE FIGHTING ALL THE TIME AND LIKING IT. I RIPPED AT HER CLOTHES, NOT CARING HOW MUCH I HURT HER. SHE SQUIRMED ON THE DIRTY FLOOR, PANTING. THERE WAS BLOOD ON HER MOUTH…. IT TASTED SWEET. SUDDENLY SHE STOPPED MOVING.

“Now,†she said. “NOW, GODDAM YOU! Now!â€

(5) You noticed, I’m sure, that among the items eliminated from the quoted passages were two “goddams.†Other words that might offend American readers’ religious sensibilities were also omitted here and there. For example, in Chapter 6 Craven tells us: “Jesus, I was tired!†Three guesses which word was dropped by Mystery Book and Popular Library.

(6) Finally and most significantly, at least for us in the 21st century, the U.S. versions deep-six Craven’s frequent habit of using our least favorite six-letter word, or its first three letters as a diminutive. This form of censorship is defensible, I suppose. But, keeping in mind that VINEYARD is narrated in first person, and that Craven seems the kind of guy who would frequently use these words, to me at least it’s also questionable. In any event it was done and we can’t undo it.

Despite changes the basic story in both versions remains the same. No attempt was made to plug the numerous holes in the plot, so that we never learn why the Princess won’t let Craven kiss her on the mouth, or what his murdered partner’s American Legion button was doing in the temple’s treasure vault.

Whichever version you read is a tribute to Latimer’s carelessness and haste. The Popular Library paperback came out alongside the first wave of Mickey Spillane novels but if the 1941 version had found a U.S. publisher back then, Mike Hammer might not have seemed so shocking after the war.

***

During the run-up to Pearl Harbor Latimer moved to southern California and began concentrating on B movie work including THE LONE WOLF SPY HUNT (1939, starring Warren William) and PHANTOM RAIDERS (1940, with Walter Pidgeon as Nick Carter). After graduating to A pictures and completing the screenplay for the 1942 remake of Hammett’s THE GLASS KEY he enlisted in the Navy, returning to Hollywood and script writing after the war.

Ten of his screenplays were for director John Farrow (1904-1963), with whom he seemed to have a special affinity. The first two established both Farrow’s and Latimer’s credentials in film noir. THE BIG CLOCK (1948) was an excellent noir about the editor of a Time-like true crime magazine (Ray Milland) who discovers that the murder he’s investigating was committed by his media-tycoon boss (Charles Laughton).

NIGHT HAS A THOUSAND EYES (1948) differed radically (due in large part, I suspect, to the devoutly Catholic director) from the 1945 Cornell Woolrich novel of the same name on which it was based, with Edward G. Robinson transformed from Woolrich’s haunted prophet to a sort of Jesus figure who goes to his death to save his quasi-daughter (Gail Russell).

Either before joining the Navy or soon after his discharge, Latimer had moved to La Jolla, California, a genteel suburb of San Diego. Late in 1946 that town became the home of the reigning monarch of his and Latimer’s common genre, Raymond Chandler. The two veterans of PI fiction and the Hollywood studios became friends. Latimer, said his more celebrated and also more reclusive colleague in crime, “knows everybody and likes everybody….†He was one of the few people who attended the funeral service for Chandler’s wife, who died in December 1954.

At the tail end of his screenplay-writing years Latimer published two stand-alone crime novels — SINNERS AND SHROUDS (1955) and BLACK IS THE FASHION FOR DYING (1959) — but these are not in the PI genre and won’t be considered here. During his final period as a writer he concentrated on television, turning out 32 scripts for the PERRY MASON series. Among those based on Gardner novels, I especially recommend “The Case of the Foot-Loose Doll†(24 January 1959); among the originals, “The Case of the Capricious Corpse†(4 October 1962).

As far as I can tell, his final TV script was “The Greenhouse Jungle†for COLUMBO (15 October 1972). He died of lung cancer on 23 June 1983, a few years after my almost conversation with him. He’s been dead almost forty years now but for my money, he and Raoul Whitfield, whom I discussed in previous columns, still rank as the most interesting PI writers between Hammett and Chandler.