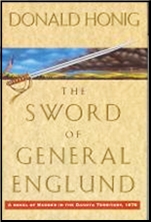

FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

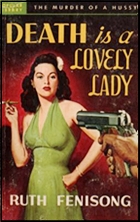

Except for Hammett and Howard Fast I don’t believe I’ve ever written about a writer who was a member of the Communist party. Unlike Hammett and Fast, the subject of this month’s column escaped the HUAC-McCarthy purge, and possible jail time, but only by dying young. His legacy includes a huge pile of non-fiction issued by various labor organizations and the Communist-run International Publishers and, perhaps more relevant to readers of this column, three crime novels.

For those interested in his life, the place to begin is Harry Carlisle’s introduction to our subject’s posthumously published journalism collection On the Drumhead (1948), which has been digitized and is accessible online. Paul William Ryan was born in San Francisco on 6 July 1906 to Irish-American parents who apparently were not well fixed. “My family kept alive by running rooming houses,” he said near the end of his brief life.

He left school at age 15 to enter the work force, initially, so he claimed, as manager of a pool hall. In his twenties and thirties he held down a variety of jobs on ships, in bookstores and elsewhere, but his main occupation was journalism. Under the byline of Mike Quin he wrote an estimated million words a year for all sorts of labor union periodicals and for newspapers like the Daily People’s World, a West Coast paper run by the Communist Party. After the USSR signed a non-aggression treaty with Hitler, who a few months later attacked Great Britain and other countries, he formed a committee to agitate for keeping the U.S. from joining the war on the Brits’ side, a committee that quickly dissolved after Hitler broke his treaty and invaded the Soviet Union.

In 1944 he married the former Mary King O’Donnell and the couple soon had a daughter whom they named Colin Michaela. Shortly after the end of World War II, under the new byline of Robert Finnegan, he turned out three well-received whodunits starring newsman Dan Banion. The series abruptly ended with his death.

There’s nothing overtly Communist in the Banion novels but, like many a 1940s movie, they tend to paint the have-not characters in virtuous colors and the haves as, pardon the expression, toads. The style is readable but, like Hammett’s, unadorned, with the vivid figures of speech we associate with Chandler noticeably absent. If the trilogy had made it to Hollywood, perhaps the ideal star to have played Banion would have been John Garfield, and any number of actors who were blacklisted in the Fifties would have fit well in other parts.

***

From early on there are hints that the first of the trio, The Lying Ladies (1946), takes place not shortly after World War II, as its publication date would suggest, but rather back in the Depression-wracked and socially conscious 1930s. When later in the novel some of the characters listen to a radio broadcast announcing the “peace in our time” agreement between Hitler and Britain’s prime minister Neville Chamberlain, we know that the precise time is late September 1938.

The geographic setting is somewhere in the undifferentiated Midwest — Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, take your pick. We open as a penniless young tramp with a bent for poetry approaches a prosperous-looking suburban house in search of a meal, is invited inside by a vicious-looking woman and, after being fed, is asked to move some furniture in an upstairs bedroom where he’s promptly conked on the head. He wakes up the next morning in a farmer’s pasture, minus his cap, liquor-soaked and with money, jewelry and a bloody clasp knife in his pockets.

It’s no surprise when he’s quickly arrested for the murder of the housemaid who was found stabbed to death in the bedroom in which he claims he was knocked out. From the viewpoint of the reactionary local papers it’s a perfect case to attack soft-on-bums policies. Banion, a reporter in the area’s big city, is sent out to exploit the situation politically but, being a man of good will and friend to those who have no friend, he quickly becomes convinced that the young vagrant has been framed.

The jailed youth’s description of the woman who fed him leads to the madam of the local brothel, which survives by paying off the proper officials, and to a hooker with a heart of gold who sets out with Banion and a compassionate farmer (who could easily have been one of John Steinbeck’s Okies) to clear the young man. Besides the stripped-down prose there’s another feature that recalls Hammett, namely the Thin Man-style sex banter, in which Banion engages not only with his lovely wife Ethel but with just about every attractive woman he meets during the case.

Anthony Boucher in the San Francisco Chronicle (31 March 1946) called Finnegan’s debut a “[l]ong full-bodied story, rich in well-sketched characters and vigorous action,” and described Banion as “having a sense of social responsibility unique in the field.”

***

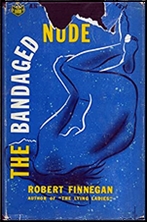

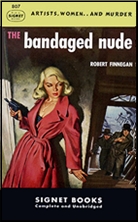

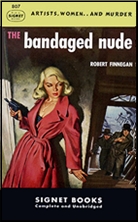

The Bandaged Nude (1946) was published in the same year as The Lying Ladies but was obviously written not long before publication, as witness its setting in post-WWII San Francisco with its housing shortage, rampant inflation and, most striking of all, a specifically postwar malaise, expressed in several ways including some poems written by various characters. Banion has seen combat but Ethel has died while he was in the army and, even though he’s gotten a job as reporter on one of the city’s papers, like so many protagonists of noir novels and movies he’s at an existential loose end.

One morning, while happening to drop in at the Hall of Justice, he’s invited to take a look at a recently discovered dead man, found with a weird green stain on his lips in a crate of ruined spaghetti about to be incinerated. He recognizes the body as that of a young vet and former artist with the Harry Stephen Keelerish name of Kenton Kipper whom he’d encountered in a saloon the previous night, trying to find out what had happened to one of his works, the nude painting of the title, which used to hang over the bar.

For no good reason — or as Tony Boucher described it, “prompted…by an odd sense of human fellowship” — Banion doesn’t identify the dead man but sets out on his own to avenge him. That green stain on his lips is soon discovered to come from a rare poison called leumatine which, turning up no hits on Google, I assume Finnegan concocted ex nihilo. Banion quickly learns that not just the nude but every one of the paintings Kipper sold before going into the army have been bought by a mysterious character who goes by a different name for each transaction.

Easing himself into San Francisco’s rather bohemian arts community, Banion interacts with a number of characters in Kipper’s life including his ex-wife (a Film Noir Woman of the first water), her estranged second husband, an obese homosexual art dealer and a sleazy PI. Eventually there are two more leumatine murders, one of them in Banion’s presence, and he himself narrowly misses becoming a fourth victim.

Between poisonings comes a lot of pursuit through the city, so much so that readers from outside the Bay Area could have profited if a San Francisco street map had accompanied the book. About two-thirds of the way through the novel one may begin to suspect who’s guilty, but few will stop reading until after the climactic fistfight between that person and Banion. Finnegan, said Boucher in his review, “has something affirmative and warming to say about people, and he says it here even better than before….”

That review was published in the Chronicle for 30 March 1947. In May of that year Finnegan was diagnosed with cancer and told he had two months to live. The doctors were not far off: he died on 14 August, age 41. His third and final novel was published the following year.

***

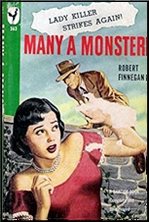

By far the bloodiest of the trilogy, Many a Monster (1948) has been described as one of the first serial-killer novels, although I disagree with the label because all the murders turn out to be connected. We open with the escape of a disturbed WWII vet on his way to an institution for the criminally insane after being convicted of the murder and dismemberment of three young women. (I know he couldn’t have been going to such an institution unless he’d been found not guilty by reason of insanity, but Finnegan is not a lawyer.)

Banion is assigned by his city editor to check out all the people closest to the fugitive: his sister, his ex-wife, his present girlfriend, a Marine buddy, and others. After the brutal murder of the sister he begins to question the escapee’s guilt. His doubts lead him to quit his job, but he carries on as the murders continue, even after a white supremacist gang captures and beats him and comes close to ripping out his fingernails with pliers.

The solution is surprising but is pulled out of a hat, as it were, and leaves a few key questions unanswered. With a total of fifteen fatalities — four before Page 1, another quartet during the course of the novel and seven neo-Nazis gunned down by Banion himself, who also disposes of their Fuhrer in a brutal fistfight — one might almost think our author was setting out to become the left-wing Mickey Spillane if one didn’t know that the first Mike Hammer novel, I, the Jury (1947), came out only shortly before Finnegan’s death.

***

His death, wrote Boucher in the Chronicle, “meant the loss to the mystery field of one of its most up-and-coming new practitioners…. [M]ay he rest in peace.” (31 August 1947).

It’s tempting to speculate on what would have happened to Finnegan had he lived to, say, the biblical three score years and ten. Would he have been imprisoned like Hammett and Fast? Impossible to say. Would he have quit writing as Hammett had done long before he was locked up? Most unlikely. Like Fast, would he have turned out twenty-odd mystery novels in his late years? Perhaps. If so, he might easily have earned for himself a few sentences or a paragraph in the history of our genre instead of a footnote. But a rich and fascinating footnote, yes?