Wed 27 Sep 2023

PI Mystery Stories I’m Reading: BRETT HALLIDAY “Dead Man’s Clue.â€

Posted by Steve under Stories I'm Reading[5] Comments

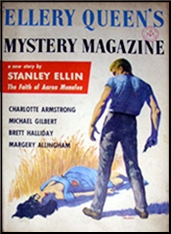

BRETT HALLIDAY “Dead Man’s Clue.†PI Mike Shayne. First published in This Week, 28 November 1954. Reprinted in Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, September 1957 and in Ellery Queen’s Anthology #9, 1965 Mid-Year Edition, in both two latter cases as “Not–Tonight-Danger.â€

As I’m sure most of you who read this blog on a regular basis already know, both “Brett Halliday†and his fictional character Mike Shayne were the brainchildren of author Davis Dresser. Over the years, though, especially after Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine had begun, but including the novels themselves, Dresser started farming out the telling of the tales to other writers, including such luminaries as Ryerson Johnson, Robert Terrall, Dennis Lynds, James Reasoner, Richard Deming, Hal Charles, and more.

But as far as is known now, only one of the stories was written by Dresser’s then wife, Helen McCloy, and by some non-pure coincidence, this is the one. It’s unusual in a way, as it’s almost entirely a puzzle story, making it no surprise that the editors of EQMM picked up it for inclusion in both their magazine and a later anthology they did.

It begins with a client coming to Shayne with a strange confession. To warn his wife about being careless about her purse, he “steals†it from her in a crowd of people, only to discover he’d stolen the wrong one. In one those equally strange coincidences that happen in fiction more often they do in real life, a valuable diamond medallion had been stolen that same evening in the same hotel.

When Shayne’s client is found murdered, though, any idea of coincidence is immediately rejected. The only clue is a strip of paper with writing on it found in the stolen purse belonging to someone else, thus transforming the tale from that of an ordinary PI story to that of a clever puzzle to be unraveled. Shayne is up to the task, however, in the hands of behind the scenes author Helen McCloy, known for her many works of classic detective fiction. It ends perhaps a little more quickly that I might have liked, but this is still a small “gem†of a story,