Sat 8 Jul 2023

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: SHORT CUT TO HELL (1957).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[4] Comments

SHORT CUT TO HELL. Paramount Pictures, 1957. Robert Ivers, Georgann Johnson (debut of both), William Bishop, Jacques Aubuchon, Murvyn Vye. Screenplay by Ted Berkman and Rafael Blau, based on the screenplay by W. R. Burnett for This Gun For Hire (1942) and the novel A Gun for Sale by Graham Greene. Directed by James Cagney.

With apologies to film critic Bosley Crowther, Short Cut to Hell certainly is.

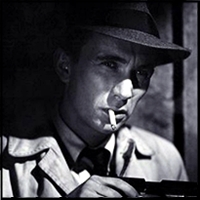

James Cagney’s debut as a director, and his only film as one, is a mess by any measure, not the least the absolute failure of this two stars making their less than stellar debut in two of the least charismatic screen performances imaginable.

Watching this it is hard to believe the legendary Cagney who worked with some of the finest directors in Hollywood like Wellman, Walsh, and Curtiz, could have picked up so little or produced so pedestrian a film, pedestrian being a compliment because this often looks like a bad half hour episodic television cop show of the era.

Whatever Graham Greene thought of the original 1942 version of his novel A Gun for Sale, filmed under its American title This Gun For Hire, there was no denying the extraordinary appeal of its cast: Alan Ladd as the emotionally and physically scarred gun man Raven, Veronica Lake as Ellen, a sexy smart young singer/magician caught up in Raven’s mission, Laird Cregar as the effete double crossing club owner who hires Raven and then betrays him, and Robert Preston as Ellen’s policeman boy friend.

In that version, the plot moved from London to LA, and Raven changed from a man scarred by a cleft lip to one with a twisted wrist, Raven kills to cover up a crime for Cregar’s character who then betrays him to the police. Raven escapes swearing revenge on Cregar and whoever employs him, runs into nightclub performer Ellen on the way to LA for a job and ends up taking her hostage as she awakens his long buried humanity and sense of decency. Meanwhile Ellen’s boyfriend Robert Preston is the policeman hunting Raven, especially once he discovers Ellen is his hostage.

That film made iconic stars of Ladd and Lake, who went on to be teamed in multiple films and was a major success for the studio.

Not so much Short Cut to Hell.

Here we meet Kyle (Robert Iver, changed from Raven and chosen because Chad seemed too tough sounding, I assume) who lives in a rundown hotel with his cat who he obsesses over while violently spurning the advances of the daughter of the manager (Yvette Vickers) who is attracted to and repelled by the slender slight killer.

Kyle cold bloodedly assassinates a young engineer and his secretary who threaten to reveal a crime by his employers and meets effete Jacques Aubuchon at a small restaurant to be paid, not knowing Aubuchon plans to claim the sequential bills he has paid Kyle were stolen from him, and knowing Kyle let him shoot it out with the cops and die.

Enter policeman William Bishop assigned to the case, whose performer girlfriend Glory (Georgann Johnson) is leaving for LA to work in a club rather than marry him.

Kyle escapes and Kyle, Aubuchon, and Glory all end up on the train to LA where Kyle takes Glory hostage.

From there the film pretty much follows the Greene novel and the 1942 film in terms of plot, but only in terms of plot.

Otherwise it bears the same relationship to the classic film that Abbot and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde bears to the Oscar winning Frederic March version directed by Rudolph Mate.

Let’s start with Ivers, a wanna be James Dean type with the charisma and screen presence of unbuttered toast. Perhaps he did better in later performances, but I see no evidence of that here. What is supposed to be a smoldering killer with budding humanity beneath the ice cold mask instead looks slightly petulant and somewhat constipated as if his chewing gum lost its flavor.

I have seldom seen a worst performance in a film from a major studio, or a less compelling one. Compared to Ivers, Alan Ladd was Olivier.

Our other debut Georgann Johnson as Glory isn’t much better though somewhat more animated and certainly better to look at. Without the teasing peek a boo mix of playful sensuality and smoky sexuality that Lake exuded, the character of Glory just doesn’t make much sense. There is no reason for her to feel anything but fear of Iver’s Kyle, so her protection of him and aid seem perverse and a bit stupid. Minus the visible sparks that flowed on screen between Ladd and Lake, the plot doesn’t make much sense without Greene’s novelist voice to carry us through.

No one else fares much better. William Bishop was always better cast as charming bad guys, and Jacques Aubuchon has the unenviable task of following Laird Cregar in the role of the cowardly immoral and effete bad guy , and frankly rather than a sense of menace and vague depravity, he only communicates dyspepsia and the snobbery of a punctilious head waiter at a second rate French restaurant.

Murvyn Vye appears as Aubuchon’s sadistic chauffeur in a noirish touch, but it is so blatant and so flat that it comes across as unintended humor rather than noir. Unintended humor is pretty much the definition of this film that is often laughably off key, thanks to the performers and script.

One dramatic scene where Kyle kills a cat to keep it from revealing his hiding place is supposed to be played for his horror and anguish at what he has done, but plays more like a Monty Python sketch gone horribly wrong.

Painful as it is to write, James Cagney comes in for his full blame for this as well. His direction is unimaginative and pedestrian. He disdains any use of light and shadow beyond the simplest of shots, his camera is objective and cold, mostly in two shots and long shots even when extreme closeups would seem unavoidable, and he shows no sense of pace or suspense much less cinematic flair unfolding his story as static as episodic television at its most unimaginative.

It is not surprising a man of his taste didn’t venture into the director’s chair again after this. I applaud his recognition of his limits.

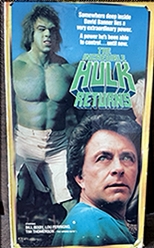

Short Cut to Hell was remade in 1979 as made for TV movie with Robert Wagner and Lou Antonio. I only hope it was better than this.

There is a language of film, and it is always disappointing when someone you expect to know it intimately proves deaf to its rhythms and lyric style. This film is actively bad, perhaps not a bomb, but empty and devoid of any sense of style. It isn’t Ed Wood, and I am not suggesting that, but the combination of James Cagney, Graham Greene, W. R. Burnett, and a classic film should have been more than this.

It is currently on YouTube, and I can only say if your curiosity overcomes you, watch at your own peril.