REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

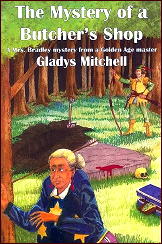

RONALD KNOX – Still Dead. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1934, Pan #223, UK, paperback, 1952. US edition: E. P. Dutton, hardcover, 1934.

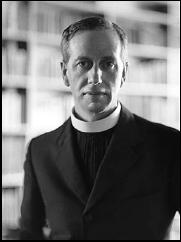

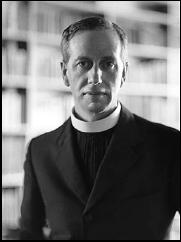

Ronald Arbuthnott Knox typifies many British writers and readers of detective fiction in that period between the World Wars we call the Golden Age of detective fiction.

Although in her recent short genre survey, Talking About Detective Fiction (2009), mystery doyenne P. D. James has written that it was Dorothy L. Sayers in the middle 1930s who made detective fiction intellectually respectable (with such “manners” crime novels as The Nine Tailors and Gaudy Night), in fact intellectuals were attracted, both as readers and writers, to detective tales at the very beginning of the Golden Age (roughly 1920), because of those tales’ ratiocinative appeal as puzzles.

For these individuals, the intellectual appeal of detective novels lay in the quality of their puzzles, not in any attempts on the part of their authors to ape the mainstream “straight” novel with compelling portrayals of social manners and/or emotional conflicts. Indeed, too much emphasis on such purely literary elements initially was often seen by common readers and more lofty genre theorists alike as detrimental in detective novels, because such an emphasis distracted readers’ minds from cold analyses of clues in their attempts to solve mystery puzzles.

One of the major literary standard-bearers for this now obsolescent view of the detective novel was an undoubtedly intellectual mystery fan and mystery writer, Ronald Knox.

Knox, a son of the Bishop of Manchester and an Eton and Oxford educated classical scholar who converted to Catholicism in 1917 (soon becoming a priest and one of England’s most prominent and articulate Anglo-Catholics), published his first detective novel, The Viaduct Murder in 1925.

Two more detective novels appeared in the 1920s (The Three Taps, 1927, and The Footsteps at the Lock, 1928), as well as Knox’s famous Detective Fiction Decalogue, wherein he laid down rules for the writing of detective fiction (all of which emphasized the puzzle aspect, or “fair play”).

On the strength of these accomplishments, Father Knox was invited in 1930 to become a founding member of the Detection Club. Three more detective novels would follow — The Body in the Silo (1933), Still Dead (1934) and Double Cross Purposes (1937) — before Knox gave himself completely over to his religious scholarship.

Less donnishly facetious than the 1920s tales, The Body in the Silo and Still Dead are commonly considered to be Father Know’s best detective novels, though oddly, they are two of the most difficult to find.

(AbeBooks lists the following number of copies for each Knox mystery title: Viaduct Murder, 27; Three Taps, 20; Footsteps, 35; Silo, 7 — all in German or French; Still Dead, 17 — though 12 of these are Pan paperback editions ranging from thirty to fifty dollars; Double Cross Purposes, 12.)

Both novels are worth reading for fans of the pure puzzle sort of detective novel, having rigorously fair play problems that even include numbered footnotes giving the pages where clues were earlier given. My preference goes to Still Dead, for its Scottish setting, over Silo, with its more hackneyed (but perennially popular) country house locale, though admittedly this is a purely literary consideration.

Still Dead concerns the death of Colin Reiver, the thoroughly undesirable heir to the Dorn estate in Scotland. Colin’s dead body was glimpsed by one of the estate’s employees, but had disappeared by the time he had left for help and returned to the spot with others.

Two days later, however, the body reappears at the same spot (still dead, hence the title). Colin is pronounced to have died from exposure, but is that really true and, either way, why were morbid shenanigans played with the corpse?

If Colin was murdered, there is no shortage of suspects. There is another employee, a gardener, whose child was run down by a drunken Colin (the latter was exonerated in court on the strength of false testimony from an Oxford friend). There are several family members, including Colin’s own father, Donald, as well as Colin’s sister, brother-in-law and cousin (truly, nobody liked Colin). There’s a family physician and also a leader of an odd religious sect to which Donald Reiver adheres.

The police write off the case (all to the good, since Father Knox evidently knew nothing about police procedure), but insurance investigator Miles Bredon (Knox’s series detective in five novels and a single, classic, short story, “Solved by Inspection”) is called in, because the question of when Colin actually died bears directly on a crucial insurance settlement (the dissolute Colin was heavily insured in his father’s favor and the Dorn estate is sadly diminished).

Still Dead starkly reveals both Father Knox’s strengths and weaknesses as a detective novelist. Positively, the fair play cluing is exemplary and reading the solution is quite enjoyable. Negatively, human interest is minimal and the plot moves very slowly.

Aside from a gentrified old lady at a hotel, Colin Reiver’s military martinet-ish cousin and a eugenics-professing doctor, none of the characters has a semblance of interest. Even these three aforementioned characters don’t come to life as they might have, given the basic material.

To be sure, Knox provides a little lightly humorous verbal byplay, courtesy of Miles Bredon’s wife, Angela (she always seems to accompany him on his investigations, despite having a child — or children, Knox is inconsistent on this point — at home). Yet Miles and Angela are no Lord Peter and Harriet, despite having preceded them into print as a mystery genre male-female duo by three years.

I found Still Dead rather more slow-moving than novels by Freeman Wills Crofts or John Rhode from this period, because Bredon’s investigation is peripatetic. Knox’s fictional works lack the relentless narrative investigative drive we see in mystery tales by those other, “humdrum”, authors, who focus so resolutely on the problem. Nor is Knox’s problem itself, though well-clued, as interesting as the alibi and murder means conundra presented by Crofts and Rhode, respectively.

In the blurb for Still Dead, Father Knox’s English publisher, Hodder and Stoughton, called Knox “a master of the English language.” Indeed, Knox is a very good writer; yet his strength as a writer is that of an essayist, not a novelist. Scattered throughout Still Dead are some fine scenic descriptions, pithy observations on religion and interesting digressions on the fate of England’s aristocracy, the nature of English gardens, chess, books, caves, hotel, etc., but, while they are interesting in themselves, by themselves they do not sustain the dramatic situation desirable in a crime novel.

Of course Knox would counter that he was merely trying to provide readers with a good puzzle, and this is a perfectly reasonable point. Admittedly, Still Dead is a good puzzle. Yet the basic material here — a dissolute gentry heir having killed a young child while driving inebriated — is interesting enough to have deserved a more serious treatment.

Knox’s handling of the material is too much on the dry side, even in the final chapter when the philosophical implications of the problem are discussed by the characters (though this is a good discussion).

Indeed, just a few years later Nicholas Blake (the pen name of poet Cecil Day-Lewis) took a rather similar plot and injected it with real human pain and suffering, in The Beast Must Die (1938), a tale much better-remembered today than Still Dead.

Even Agatha Christie, one feels, would have made a more compelling tale of Still Dead. There seems to me to have been an evident reluctance on the part of Father Knox to grapple with deeper emotions in his detective novels. (One sees this quirk as well in the half-dozen mild mystery tales by a Knox contemporary, Anglican minister Victor Whitechurch.)

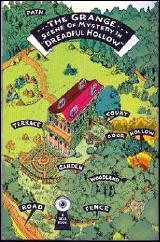

Despite these reservations on my part, Still Dead is well worth reading for admirers of classical British mystery. If you can find a hardcover copy (as least this is true of the British edition by Hodder and Stoughton), you also will find a beautiful endpaper drawing of the Dorn estate and a dramatic frontispiece of stark Dorn House, both by Bip Pares, as well as that footnoted clue page guide.

The Pan paperback editions of Still Dead from 1952 that booksellers want thirty to eighty dollars for lack these graces, so charmingly redolent of the Golden Age detective novel, when many writers in their mystery tales unashamedly emphasized puzzles.

Editorial Comment: In my review of Knox’s The Three Taps earlier on this blog, I included his list of the “Ten Commandments for Detective Fiction,” also referred to by Curt.