Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

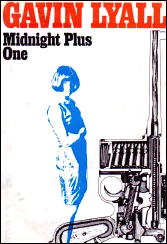

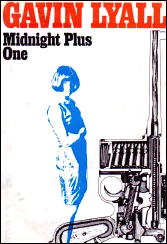

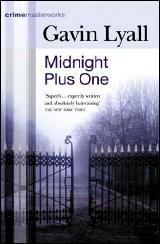

GAVIN LYALL – Midnight Plus One. Hodder & Stoughton, UK, hardcover, 1965. Charles Scribners Sons, US, hardcover, 1965. Paperback reprints include: Pan, UK, 1967; Dell, US, 1969; Orion, UK, 2005.

It’s a cold wet April in Paris, and Lewis Cane is nursing a drink in a small cafe when he is suddenly thrust into his own violent past.

The loudspeaker on the wall said: “Monsieur Caneton, Monsieur Caneton. Téléphone, s’il vous plait.”

Ask me what my wartime code-name was and I’d need a moment to remember. Broadcast it over a café loudspeaker in Paris and I know immediately who you mean. The back of my neck felt cold, as if somebody had touched it with a gun muzzle.

Cane, Caneton was a gunman working with the Resistance. He has old friends and old enemies, but luckily this is a friend, Parisian lawyer Henry Merlin and one time Resistance paymaster. The two men haven’t seen each other since the war, but it is no simple meeting.

Like Cane Merlin is involved in the scheme to get a man named Maganhard from a boat off the coast of Brittany to Lichenstein, where he is to accomplish a dicey bit of business. A simple job as Merlin describes it: “A client wishes to go from Brittany to Liechtenstein. Others wish him not to go. Shooting is possible. You wish to help him get there?”

Maganhard has been framed on a rape charge to delay him getting to Lichenstein for his tricky bit of banking so both police and his enemies want to stop him. Cane will have to take him across country by car.

Cane takes the job and learns he will not be alone, a young American gunman is going with him. Cane’s job is primarily as the driver and to back the American gunman; Harvey Lovell, the third best in Europe, an ex-agent of the American Secret Service.

But Lovell comes with baggage Cane doesn’t need:

It might have been a haunted face, but if so, it was used to its ghosts by now… Not a face that had seen hell — but perhaps one that expected to.

I grabbed for a cigarette. Maybe I was imagining things. I hoped so: I wanted a sensitive gunman as much as I wanted one with two tin hands.

Part of the fun of any Lyall novel is his considerable know how about guns and the business of guns. He neither romanticizes nor fantasizes about them, but presents them as tools in a deadly game.

“You need a thirty-eight round to have any punch,” he said, with careful calmness. “Thirty-eight automatic would be a sight heavier and a sight bigger. Automatics can jam, too.” But by now I was hardly listening. I wasn’t really interested in his opinions on guns — only that he had some. To a man who bets his life on his choice of guns there’s only one True Belief about guns — his own — and the only True Prophet is himself. Every one has a different belief, of course, which is why there are still so many gunmakers in business.

And in Lyall’s sure hand even inanimate objects can become characters:

Once we were clear of the town, I started trying the car out: shoving on the accelerator, throwing it into bends, stamping on the brakes. I hadn’t driven a Citroën DS for a couple of years, and while it’s a damn good car, it’s also a damn peculiar one. It has a manual gear-change but without a clutch; a front-wheel drive — and everything works by hydraulics. Springing, power steering, braking, and gear-change — all hydraulic. The thing has more veins in it than the human body — and when they start to bleed, you’re dying.

Maganhard is accompanied by his secretary Helen Jarmian, and Englishwoman, and she and Lovell are soon drawn to each other in the increasingly dangerous journey through the cold wet French spring.

It soon becomes obvious why Lovell has that haunted look. He has a problem with drinking, a bad habit for anyone, but fatal for a gunman.

Cane finds himself with a dipso gunman, a dubious client, a cranky car, and a woman on a job that would be difficult enough in any case. And the enemy has already shown its hand, murdering the driver that delivered the car.

The journey is dangerous and tense, and soon enough explodes in violence. Violence that pushes Lovell back to the bottle at the worst time.

Harvey shifted in his seat, rubbed his face again and sneaked another look at his fingers. He just spread them open in front of him — not as obvious as stretching them full out at arms’ length the way doctors make you do it, but clear enough if you knew what he was up to. The fingers were shaking like a hula dancer’s hips.

He turned his head slowly and looked at me. His face was blank — as blank as his face could ever be. It was still a face that would know hell when it saw it, but it didn’t show what it knew now.

Except that I could guess. I said: “You need a drink.”

He looked at his spread fingers again, with no more emotion than if he was deciding he needed a manicure. Then he said slowly and simply: “Yes. I’m afraid I need just that.”

But Lovell manages to prove himself an efficient killer even drunk. And worse, the game isn’t as simple as it might seem and as Caneton knew, even if Cane may have forgotten, nothing is ever clean and simple in this violent world, and men play both ends against the middle with the dead bodies collateral damage.

Nor can Cane get around who he is — or was, and as the violent conclusion draws near he finds he can’t just walk away, because of who he once was and what that meant:

But Maganhard is right and Alain is wrong… And me? Then I knew that nothing I could do would ever change either of those things. All I could do was fix the cost — the cost of being right or wrong. And perhaps who paid.

Slowly, very slowly, I lifted my left wrist and laid it across the barrel of the aimed gun and flickered my eyes for an instant at the luminous dial of my watch.

Three minutes. Just time to go back, to say the hell with twelve thousand francs and being Caneton. To tell Maganhard he’ll still be in the right whether he gets through or not, and that what matters is the cost…

But still time enough to fix the cost, to make that right. Because it was still the fight I’d planned and not what Alain was expecting. Because I was still Caneton — and nobody else was that. And I could get round that corner.

The ending is dark and powerful. Lovell has learned he can kill and drink, and Helen Jarmian who loves him, loves him too much to see how deadly that will be for them both. It’s the sort of thing Caneton alone can resolve.

And perhaps she was right. Perhaps I was still Caneton. And perhaps — I looked at her, then at Harvey; at the haunted, lined face that was, in an odd way, so innocent because it showed its guilt so clearly.

I said: “How’re the shakes?”

He stretched his right hand towards me, fingers spread.

They were as steady as carved stone. He smiled down at them.

I said: “Pretty good,” and then swung the Mauser over and down. I heard — and felt — the fingers crack.

It’s a stunning moment, no less to the characters than the reader:

Miss Jarman looked at me, her eyes hard and bright. “You didn’t need to do that.”

“It was cheap, simple, a bit nasty,” I said dully. “What Caneton would have done. If I’d been somebody else maybe I’d’ve thought of something better. But I’m not.”

Harvey half opened his eyes and whispered hoarsely: “You’d better hide good, Cane. Real good. Because I’ll spend a long time looking.”

I nodded. “I’ll be at Clos Pinel — or they’ll know where.”

Somewhere between Ian Fleming and Raymond Chandler, Lyall is one of the masters of the British thriller, combining the poetry of the Buchan school with the action of Alistair MacLean and the toughness of a Hammett.

His books include classics of the form like The Most Dangerous Game, Shooting Script, The Venus Pistol and others, including the critically acclaimed Harry Maxim series.

I’ll grant I’m not the least objective about this book or Lyall. He is simply one of my all time favorites, and Midnight Plus One the best of his many books. I was sixteen when I first read it, and I’m happy to say it holds up as well today as it did then.

If you want to see the British thriller done as it should be by one of the best writers of that genre read this one. Read anything by Gavin Lyall. The man could not pen a bad book, and this one is his masterpiece.

Halfway down the mountain I remembered that I’d never collected the balance of my pay — four thousand francs. I kept on going, but looked at my watch. It was a minute after midnight. Ahead of me, the mountain road was a dark tunnel without any end.

Editorial Comments: According to Wikipedia, the film rights to Midnight Plus One were purchased by actor Steve McQueen not long before he died. If this is so, a great opportunity was lost — just my opinion, of course.

For a lengthy overview of Gavin Lyall and his work, and an abundance of cover images, check out Steve Holland’s Bear Alley blog. (Two of the cover images found here came from there.)

Steve’s essay, written in September of last year, ends by saying, “It’s sad to think that only one of Lyall’s novels (Midnight Plus One) is currently in print.” Has anything changed since then? I don’t believe so.