Thu 3 Jun 2010

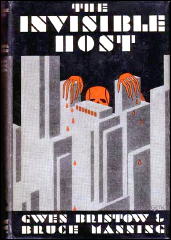

A Review by Jim McCahery: GWEN BRISTOW & BRUCE MANNING – The Invisible Host.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[4] Comments

GWEN BRISTOW & BRUCE MANNING – The Invisible Host. Mystery League, hardcover, 1930. Play: The Ninth Guest, by Owen Davis (on Broadway Aug-Oct 1930). Film: Columbia, 1934, as The Ninth Guest (with Genevieve Tobin & Donald Cook; director: Roy William Neill). Paperback reprint: Popular Library, 1975, as The Ninth Guest.

Two of the earliest and most popular writers for the highly successful Mystery League were the husband-and-wife team of Gwen Bristow and Bruce Manning, both one-time reporters on rival newspapers in New Orleans.

This first work is sheer melodrama at its best (if such is possible) as a cast of eight guests is invited by telegram to attend a penthouse surprise party in New Orleans; each guest is led to believe the party is in his/her honor. The only problem is that none of them are permitted to leave and death awaits each in turn, as their host explains to them over the radio.

Any comparison with Dame Christie’s And Then There Were None stops here. There is a definite undercurrent of hostility between various members of the ill-fated gathering, and suspicion runs high as to who is actually behind the macabre dinner.

The host challenges them to his life-or-death game over radio station WITS, promising himself as a final victim if he fails to kill them all, each of whose secrets and idiosyncrasies he seems to know so thoroughly.

Against the prerequisite background of thunderstorm and candlelight with all avenues of escape blocked and eight coffins awaiting them on the patio, the guests fall one by one by various pre-arranged death devices, including poison, electricity, needles and (Pen readers take note) a final death by a poisoned pen.

The host cleverly counts on his guests’ known habits to plan and even predict their various deaths.

While necessarily shy on characterization, and requiring a more-than-normal amount of suspension of disbelief on the reader’s part, it would be unfair not to admit to some good surprises and a good overall job of construction on the part of the authors.

You may recall having seen the 1934 Columbia film on television which was made from the play version, both of which were entitled The Ninth Guest — and there was one, by the way, but you’ll have to read the book if you want to find out who it was.

Note: David Vineyard reviewed this book a few posts back. Follow the link to find it. In the same issue of Poisoned Pen, Jim also reviewed Bristow and Manning’s The Gutenberg Murders, another Mystery League adventure. Look for it posted on this blog sometime soon.

Editorial Comment: Jim McCahery died in 1995 at the age of 61, far too young. He lived in New Jersey and was an avid reader and collector of mystery fiction. He was also the author of two crime-solving cases of Lavina London, a retired radio star and amateur detective, books that were both published in the 1990s.

I met Jim in person once or twice as a fellow member of DAPA-Em, and he was a close friend of Jeff Meyerson, who published The Poisoned Pen, and who has given me permission to reprint not only this, but other reviews that Jim wrote for him over the years.