REVIEWED BY CURT J. EVANS:

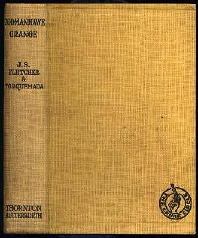

J. S. FLETCHER – Todmanhawe Grange. Thornton Butterworth, UK, hardcover, 1937. US title: The Mill House Murder, Alfred A. Knopf, 1937.

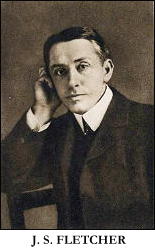

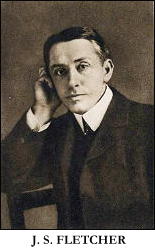

The final mystery novel by the extremely prolific mainstream and mystery genre novelist J. S. Fletcher, Todmanhawe Grange was published posthumously, two years after the seemingly indefatigable author’s death in 1935 at nearly seventy-two years of age.

Completed by Edward Powys Mathers, aka Torquemada, the infamous crossword puzzle creator and crime fiction reviewer for the London Observer (who himself died at the age of forty-six four years later), Todmanhawe Grange is, surprisingly enough, given that it came at the end of a long line of over eighty Fletcher mystery novels, the best Fletcher crime tale I have read.

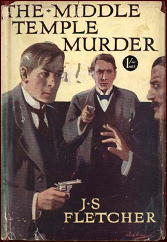

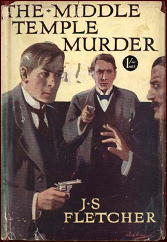

J. S. Fletcher turned to the mystery and thriller genre in 1901, after enjoying some success as a mainstream novelist, particularly as a regionalist in the manner of Thomas Hardy and Eden Phillpotts. Though Fletcher continued to write mainstream novels (largely about his native Yorkshire), mystery tales increasingly dominated his output, especially after the publication in 1919 of The Middle Temple Murder, the mystery famously praised by President Woodrow Wilson.

Alfred Knopf, Fletcher’s canny American publisher, never tired of reminding the reading public of this fact; and whether because of this or some other reason (Knopf’s publicity campaign probably was the best by an American publisher prior to Charles Scribners’ promotion of S. S. Van Dine in the second half of the 1920s), Fletcher became known for a time in the United States as the greatest English mystery writer after Arthur Conan Doyle (this view was not shared in England).

Fletcher, who naturally enjoyed the money this publishing success was bringing in, responded by producing ever more works of mystery fiction, both novels and short story collections. Many of his earlier, pre-Middle Temple Murder mystery novels that had not originally published in the United States were reprinted at this time as well (without informing readers that they were reprints), resulting in the regular publication of four or more Fletcher mystery volumes a year. Not for nothing did critics refer to the “Fletcher Mill.”

By the 1930s the Fletcher vogue had passed and Fletcher was seen even in America as a passe, unexciting writer. Better detective novelists like S. S. Van Dine, Ellery Queen, Agatha Christie, Dorothy L. Sayers, Anthony Berkeley, John Rhode, J. J. Connington, and Freeman Wills Crofts had become well-known, and simultaneously Fletcher’s mysteries, never the most inspired in truth, largely had become ever more mechanical and dull.

After his death, his books quickly fell out of print and today he survives in mystery genre history essentially as a one-work writer, the author of The Middle Temple Murder (praised — did I mention? — by Woodrow Wilson).

So imagine my surprise when I read Todmanhawe Grange and found that it was quite good, succeeding both as a puzzle and a crime novel of atmosphere and local color.

Surely some of the credit for the merit of the puzzle must go to Torquemada (Fletcher tended to be a loose mystery plotter, often eschewing the fair play convention of the Golden Age), yet the novel is as well the most atmospheric and engrossing crime tale that Fletcher had written in some years.

In Todmanhawe Grange, we read of the last exploit of Ronald Camberwell, a private inquiry agent introduced by Fletcher late in his writing career, in 1931. Camberwell himself is not particularly interesting, but the setting, a Yorkshire mill town, is very well-conveyed, as are the people residing there.

The murder centers around the affairs of James Martenroyde, head of wealthy textile manufacturing family. Martenroyde, affianced to a much younger woman, contacts Camberwell’s firm to investigate certain delicate matters. The blustery night of Camberwell’s arrival in the mill town, John Martenroyde is found dead in the mill weir. His death, of course, is not a natural one.

Two additional murders follow — as well as Fletcher’s much-loved lengthy inquests — and the reader is kept engaged throughout all these events, even the inquests (much of the second inquest was written by Torquemada, who provides excellent material and forensic detail that Fletcher himself tended to scamp in his mysteries).

The tale takes a rather Gothic twist and ends up bearing some resemblance, interestingly, to something out of the mind of Ruth Rendell (writing as Barbara Vine).

As pointed out earlier, a goodly share of the credit for the success of Todmanhawe Grange must go to Torquemada, yet he wrote, according to his own admission, only the final quarter of the tale (except for the very last line, which followed Fletcher’s last dictates; the rest of the conclusion followed an outline).

For whatever reason, Fletcher seems to have put some extra effort into the last work, and the effort shows.