Fri 26 May 2023

A TV Episode Review by David Vineyard: BOB HOPE CHRYSLER THEATER “A Killing at Sundial” (1963).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , TV Drama[4] Comments

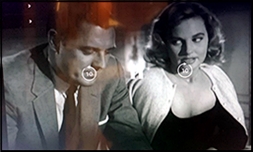

BOB HOPE CHRYSLER THEATER. “A Killing at Sundial” NBC, 04 October 1963 (Season One, Episode One). Stuart Whitman, Melvyn Douglas, Angie Dickinson, Joseph Caliea, Robert Emhardt, Malcolm Atterbury. Teleplay: Rod Serling. Directed by Alex Segal. Currently available for streaming on YouTube (see below).

Sundial is a small Southwestern town slowly wilting under a drought that has bankrupted the town Boss Pat Konkle (Melvyn Douglas) has put most of the residence deep in debt and burdened with unpaid mortgagees. As the hot dusty town threatens to dry up and blow away under the onslaught of poverty and heat, an unlikely savior appears: Billy Cole (Stuart Whitman), an Indian whose father the town lynched before driving Billy out of town years earlier.

Billy is bitter, ironic, and recently oil rich, interested only in putting a burr under Konkle, not even in renewing his one time interest in Konkle’s beautiful daughter Susan (Angie Dickinson).

The only person in the world he cares about is Cagewa (Joseph Caliea), an old chief who was mentor and savior to Billy after his father was lynched, and Cagewa fears what it is Billy has come back for.

That something is revealed at an impromptu service at his father’s unmarked grave Billy invites the town folk to. He has bought all their mortgages and save the town for a price — Pat Konkle dies before morning.

How, who, none of that concerns Billy. All the wants is Konkle dead before the next sunrise.

Cagewa is horrified, as much by the willingness of everyone to do the job. Susan tries to explain her father is a broken man who has lost everything. None of that matters to Billy. He will watch as the day winds down and the long hot night rolls by while Konkle becomes more and more aware his many years of Boss rule have won no champions, no friends.

He is going to die before morning comes.

“Killing at Sundial†was the first episode of the Bob Hope Chrysler Theater in the first season in color in 1963. Aside from a strong cast, it featured a strong teleplay by Rod Serling, touching on familiar Serling elements such as racism, hate, revenge, intolerance, small town prejudice, and broken men, Billy by his hate, Konkle by his arrogance and fear, the town by their greed and desperation.

The anthology format was made for Serling, and throughout the Fifties and Sixties, he and writers like Abby Mann and Paddy Chayevsky brought high drama to the format, with Serling himself becoming a celebrity hosting The Twilight Zone and as screenwriter for films like Seven Days in May.

Despite the usual White men in Red face common to the era, this one has a strong narrative line, and fine performances all around with Douglas getting to do some fine emoting as he falls apart ,and Caliea’s quiet dignified Cagewa stealing the whole thing as he did many a film in his long career.

The finale is powerful even if predictable, ending on a surprisingly dark note for an anthology series episode from this era.

Perhaps too on the nose for modern audiences at the time, there was a freshness and power to this sort of thing, a too rare look at a darker side of the uniform and bright world many of us had grown up in. As the optimism of the era gave way to questions and fears, even the relatively sedate world of the small screen began to acknowledge that the safe prosperous world we grew up in was not the only one.

“Killing at Sundial†offers a glimpse of sunny hell, and as with most things Rod Serling did, it is worth catching.