Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

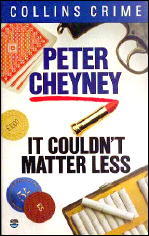

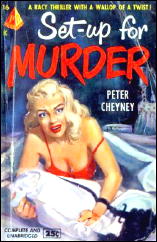

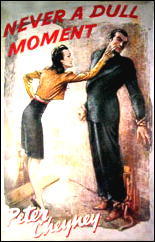

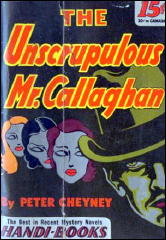

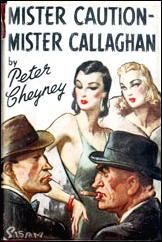

PETER CHEYNEY – It Couldn’t Matter Less. William Collins & Sons, UK, hardcover, 1941. Reprinted in the UK in paperback many times since. Mystery House, US, hardcover, 1943. Also published as: The Unscrupulous Mr. Callaghan. Handi-Books #18, pb, 1943. Also published as: Set-Up for Murder. Pyramid #16, pb, 1950.

Film: (France), 1954, as Plus de Whisky pour Callaghan! (with Tony Wright as Slim Callaghan; director: Willy Rozier).

Callaghan — sole occupant of the downstairs bar at the Green Paroquet Club — tilted his chair back against the wall, put his hands in his pockets, gazed solemnly, with eyes that were a little glazed, at the chromium fittings of the bar-counter at the other end of the room. The bartender, wearily polishing glasses, wondered when he would go.

His biographer, Michael Harrison, subtitled his book on Peter Cheyney, “The Prince of Hokum.” In many ways it isn’t far off. Cheyney was a reporter and public relations man who worked the West End club scene in London and had briefly been the secretary to Sir Oswald Mosley of the BUF (British Union of Fascists), though in fairness Cheyney got out well before Mosley and his Blackshirts turned to outright treason.

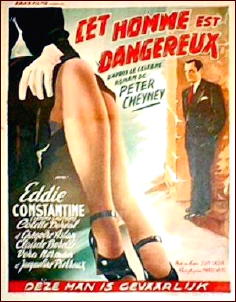

Having dropped out of school at fourteen to become a writer in 1933 he turned to mystery fiction and in 1936 he wrote This Man is Dangerous about American G-Man Lemmy Caution, a British turn on the hard-boiled school and like nothing anyone else had tried.

The language and the style of the Caution books is unique. Even Cheyney’s imitators never managed to ape it. Caution put Cheyney on the map. Along the way Cheyney also created Alonzo MacTavish a Saint like adventurer, and began his “Dark” series of spy novels that received high praise from the likes of Anthony Boucher and helped to inspire Ian Fleming and James Bond.

Considering his career only lasted from 1936 to his death in 1951, he turned out 35 novels and 150 short stories.

But most would agree his single greatest creation is Slim Callaghan, the British answer to the American hard boiled private eye who made his debut back in 1938 in Urgent Hangman. Slim belongs to the Sam Spade school of tough cynical and money obsessed eyes, less a knight in tarnished armor than a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

It Couldn’t Matter Less is his fifth outing, and was the first I read, way back in 1970. It isn’t the best of the Callaghan novels but is still one of my favorites.

The setting is wartime London. Inspector Gringall of the Yard, longtime friendly rival of Callaghan’s, has been clubbing and happens to call Slim to ask if he’s seen Doria Varette, a torch singer at Ferdie’s Place.

It’s Slim’s birthday but Callaghan knows Gringall has something up his sleeve . He goes anyway. Backstage Doria asks him to take on a job, to find her boyfriend Lionel Wilbery, a poet with the wrong friends and a drug problem:

“He was fearfully interested in writing poetry,” she went on. “… He used to write verse, mainly about the sea. He was very fond of the sea …”

Callaghan cocked an eyebrow.

“Perhaps he drowned himself in it,” he said.

Slim has hardly agreed to take the case before a slick Cuban accented thug, Santos, confronts him outside Varette’s flat, but such things don’t faze Slim.

Back at the office, Slim puts his loyal, and jealous, secretary Effie and his assistant, a long winded Canadian Windemere “Windy” Nichols, on the case and contacts Wilbery’s well-to-do Mother — might as well get paid twice for the same chore. That leads to Wilberys’ beautiful sister (beautiful women pass in and out of Slim’s life at a remarkable rate) Leonore.

Meanwhile he meets a pair of Russian refugees running the publishing house that publishes Wilbery’s poetry (one of them of course the beautiful Sabine) who tell him Varette is the poet’s drug connection. At an illegal gambling joint he runs into Santos D’Inazzi, the Cuban who tried to warn him off Varette, who slugs him, and might have finished him off if Windy Nichols hadn’t stepped in.

And of course there are the Cheyney women, as famous in their day as the Bond Girls have been in ours:

As he crossed the room he took a long look at Lenore. He thought she was definitely breathtaking …

She wore a black watered silk coat and skirt of exquisite cut. The coat was tailored on the rather severe lines of a man’s lounge jacket with a single diamond button at the waist…

A hell of a woman thought Callaghan. A woman who could start a packet of trouble any time she felt like it — and finish it too.

Things really get interesting when Callaghan breaks into Varette’s apartment and finds her dead. So he frames Santos and calls the cops. After all the guy tried to kill him. One good turn deserves another:

“You’re such a slippery character.”

“Shocking,” agreed Callaghan, “Unscrupulous too …”

“I know,” said, Gringall.

From this point on the action seldom slows. Callaghan romances Lenore, slugs it out in a West End nightclub with a pair of Santos partners, burgles the Russian publishers offices, and literally stumbles across Lionel Wilbery.

Along the way he discovers why Gringall introduced him to Doria Varette, breaks up a Nazi spy ring, and collects his considerable fees and the delicious Lenore, usually while three sheets to the wind, breaking every law in the book, and planting evidence left and right — when he isn’t concealing it from the police:

The world was a hell of a place, thought Callaghan, a hell of a place. Wars and rumours of wars. Yet underneath the great battles raging over the surface of the earth, were smaller battles, the sort of guerilla warfare in which he, Callaghan, was engaged at that moment; the kind of guerilla warfare for which, he, the ‘private investigator’ — that title which covered a multitude of activities, cleverness, slickness — and Gringall, the police-officer, found themselves, for once, allies.

Originality wasn’t Cheyney’s strength, but he did the hard-boiled patter, the tough guy stuff, and the atmosphere surrounding it as well as anyone working in the genre. Slim is in the mode of Sam Spade, Michael Shayne, Kurt Steel’s Hank Heyer, Cleve Adams Rex McBride, and Jonathan Latimer’s Bill Crane, narrated in the third person and a good deal tougher and less sentimental than the Chandler school.

Slim’s style is direct and to the point, and he could give Spade pointers on saying what he thinks:

“You can’t realize how ridiculous you sound.”

“That never worries me,” said Callaghan cheerfully. “So long as I don’t think ridiculously. For instance I should be ridiculous if I thought your mother was paying me a thousand pounds just to hang around on the off-chance of finding Lionel. She could have had Lionel found for nothing. She could have gone to the police. Well — why didn’t she …”

Care for it or not, the atmosphere of a Cheyney novel is distinct, smoky night clubs, good whiskey, and a hint of Narcisse Noir in the air. You can almost hear the torch singer and just make out the swarthy type in the dinner jacket waiting in the shadows with a knife meant for your gizzard.

But don’t worry, order another slug of rye, light another cigarette, brush off your impeccable dinner jacket, don that soft black felt hat with the dashing brim, and go into battle knowing you are sure of eye and hand — despite the amount you’ve had to drink:

Callaghan, one hand in the cigarette box, saw, out of the corner of his eye, the shape of a knuckle-duster on Wulfie’s knuckles, showing against the soft cloth of his trousers. He lifted his knee and kicked Wulfie in the stomach.

Wulfie uttered a horrible little shriek. He slithered down on to the carpet. Callaghan stooped, picked up the cigarette box, threw it as Salkey who was going for his hip pocket. The box hit Salkey in the shoulder, knocked him off balance for a moment. Just long enough for Callaghan to shoot out of the chair.

He takes Salkey’s gun away from him and kicks Wulfie in the head. Then he takes the gun and a drink and calls Effie. Cool customer, Mr. Callaghan.

Slim consumes heroic amounts of booze throughout his adventures. If you are impressed with the half a fifth of vodka James Bond consumes, or Philip Marlowe’s bottle of bourbon in his office desk, you will be in shock that Slim can even get out of his silk pajamas and into action, much less romance beautiful women and battle nasty thugs.

He does laze around and stretch his long legs a good deal, but really, Slim has to be the Olympic champion of the genre when it comes to drinking. John J. Malone and his pals the Justus’s couldn’t hold a candle to him — they wouldn’t dare. It’s a wonder he doesn’t blow himself to kingdom come just lighting a cigarette.

Slim was well played on screen by Michael Rennie in Uneasy Terms and on the West End stage by Terence De Marney and on screen by Derek De Marney in Meet Mr. Callaghan.

Eddie Constantine, who was Cheyney’s Lemmy Caution on screen, had a few outings as Slim first. Probably his best incarnation however was the principle inspiration for Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective.

Neither Cheyney nor Slim ever found much of an American audience, but he was hugely popular in England, with sales of up to five million copies a year of his books, and also loved in Europe and especially France.

Cheyney’s novel Dark Duet, was the first book published in France after the Nazi occupation, the book smuggled in from occupied Holland, and on the streets while German soldiers were fleeing Paris. Jean-Luc Goddard later borrowed Lemmy for his New Wave science fiction film Alphaville.

Anthony Boucher edited an anthology of Cheyney’s “Dark” novels, The Stars Are Dark, during the war, and Raymond Chandler praised his novel Dark Duet.

Long, lean, and angular, Slim, with a cigarette hanging from his lip and a drink or a beauty never far from his lips, is Cheyney’s best creation. There may not be a lot of surprises in his oeuvre, but his books are fun and well worth reading, and no one ever did the atmosphere of the London club scene like Cheyney.

Reading any of his books is the equivalent of a night of West End clubbing — just watch out for the hangover. Slim’s liver must be a wonder to behold.

Note: Whatever Cheyney’s pre-war politics were, he made up a little for them with many of the 150 short stories, often featuring Slim or Lemmy, that were distributed to the troops in little chapbooks of a few short tales each. The output was huge and greatly appreciated by the troops.