Reviewed by DAVID L. VINEYARD:

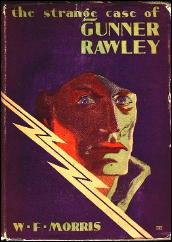

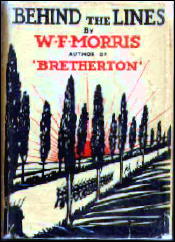

W. F. MORRIS – The Strange Case of Gunner Rawley. Dodd Mead & Co., hardcover, 1930. British edition: Geoffrey Bles, hardcover, 1929, as Behind the Lines.

Tankard, the narrator of the opening chapter of this novel, is a soldier in the British army in the First World War.

He recounts a strange encounter, when, while captured by the Germans, he saw his friend Peter Rawley in civilian clothes about to be executed by the Germans in a chalk quarry near Bapaume:

I was asked the other day … what was the quaintest thing I saw during the war…Had she asked what was the most extraordinary thing I saw I could have answered … that it was Peter Rawley I saw in that chalk pit near Bapaume …

One will say I saw him only for a moment and that it was misty at the time, and that even then I did not recognize the features covered as they were by grime and stubble. I admit all that. The circumstantial evidence is not worth a straw.

Yet I am sure that the taller of the two civilians I saw in the chalk quarry that misty March morning of 1918 was that Lieutenant Peter Rawley, R.F.A., who the official record stated was killed in Arras the previous autumn.

The novel then picks up a year earlier with Peter Rawley before the events at Arras and recounts his own strange story that began with a fellow officer, Rumbald, a charming but reckless fellow of dubious virtue:

“The worst of you fellows is that you don’t enjoy life,” went on Rumbald imperturbably… “Why the hell can’t you take what’s coming to you without being ruddy virtuous about it?”

Rawley has to give Rumbald his point, but when Rumbald later assaults Rawley during a confrontation at a forward post Rawley accidentally kills him, and panicked, deserts, which saves his life when the forward observation post is blown up by a German shell — convincing everyone that Peter Rawley is dead and Rumbald killed by the shell.

The rest of the novel recounts Rawley’s adventures dressed as a civilian behind enemy lines and his encounter with another deserter, Alf Higgins. Morris proves to be a master at depicting the loneliness of the battle zone and its eerie otherworldly quality.

They set off together in the darkness along the narrow muddy pot holed road. There was no sound accept the distant drumming of the guns and the gentle swish of the rain. The darkness hung like a curtain around them, and only once did Rawley see dimly against the sky the skeleton rafters of some shattered homestead.

Rawley’s adventures, and his and Alf’s eventual redemption when the German’s break through the British front, form the rest of the novel ending with Alf and Rawley before a firing squad about to be executed:

That curious feeling of being a spectator clung to Rawley. He heard a shell burst overhead and detonate on the hillside above him, and he noticed with detached interest that it sounded like a British sixty pounder. He also noticed with the same dream like detachment that a party of three British prisoners, including an officer, were being escorted up the road.

Alf’s face was pale under its covering of dirt, and every few seconds he moistened his lips with his tongue.

“I ’ope them blokes ’ave got safety catches,” he whispered hoarsely. “Playin’ about with firearms like that.”

Another shell came whining through the mist: its snoring hum increased rapidly to a savage resonant roar, and it burst on the side of the road with a majestic pillar of spouting earth and vibrant hum of flying metal.

The Strange Case of Gunner Rawley is an entertaining tale with a satisfying resolution, and Morris seemingly had experience in the war which he used to good effect. Though there is no detective interest per se in the book it is clearly marketed as a mystery.

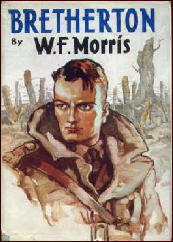

I don’t know anything about W. F. Morris save that in To Catch a Spy, Eric Ambler said of his novel Bretherton that it was one of the best portraits of a spy working behind the lines in wartime. The dust jacket from this one describes a previous novel, G.B. a Story of the Great War, as realistically weird and this one as “… a mystery story from an entirely new angle.”

Morris writes well and underplays the obvious melodrama of his story. with the theme of the loss of identity in the confusion of war dating back to The Odyssey, and well handled here. Rawley is portrayed as a human and likable man who finds himself in circumstances beyond his control and how he extricates himself from his dilemma is a well told story of the confusion of war and a “quaint” tale of wartime adventures.

Note: Though this is a novel of wartime adventure, the Dodd Mead edition is marketed as a mystery, as pointed out above, with ads for books by G.K. Chesterton, Agatha Christie, R. Austin Freeman, John Rhode, and Anthony Gilbert on the back cover; and the book is referred to as a mystery novel in the inside dust wrapper copy. Al Hubin also includes it in Crime Fiction IV.

Editorial Comment: Hubin says this about W. F. Morris, 1893-? Born in Norwich; educated at Cambridge; battalion commander during WWI; was Assistant Master, Priory School. Listed are seven novels published between 1929 and 1939, one marginally. From the titles, several of them also seem to have wartime settings.

[UPDATE] 07-03-10. [1] Earlier today Jamie Sturgeon sent me a link to an article about Morris. Check it out here.

The essay//review is incomplete online, but it’s still very informative, including as it does the year that Morris died, 1969, a small piece of data that I’ll quickly send to Al Hubin for the next installment of his online Addenda to CFIV. Mostly, though, the piece is about Morris’s book Bretherton, and it goes into considerable detail about it.

[2] Thanks to the website that David has steered me to in the Comment he left, I’ve been able to add two covers images to this review he wrote.