Sun 6 Jun 2010

From the Archives: Four Short Movie Reviews.

Posted by Steve under Mystery movies , Reviews[14] Comments

● ONCE UPON A CRIME. MGM, 1992. John Candy, James Belushi, Cybil Shepherd, Sean Young, Richard Lewis, George Hamilton. Director: Eugene Levy.

The lives of several Americans traveling in Europe converge in Monaco, with several or all of them eventually suspected of murder. A comedy, as if you couldn’t tell from the cast.

I was reminded of some of Inspector Clouseau’s earlier cases; Judy called it French farce. I agree, but I’d recommend this only if you can stand Richard Lewis.

● GOTHAM. Showtime, 1988; made for cable-TV. Tommy Lee Jones, Virginia Madsen, Denise Stephenson, Frederic Forrest. Screenwriter/director: Lloyd Fonvielle.

A down-on-the-heels PI named Eddie Mallard is hired by a man who wants his wife to stop following him around. The problem is that she has been dead for several years. A large box of jewels is also involved.

Is this a ghost story or a mystery? I’m not quite sure, and no one in the movie was either, or so it seemed to me. Jones makes a great private detective, but I lost interest about halfway through.

● SHINING THROUGH. 20th Century Fox, 1992. Melanie Griffith, Michael Douglas, Liam Neeson, Joely Richardson, John Gielgud. Based on the novel by Susan Isaacs. Director: David Seltzer.

A Brooklyn secretary, half-Irish, half-Jewish, somehow becomes a spy at the outbreak of World War II. More than that, since she knows German, she soon finds herself in Berlin trying to track down the factory making U-2 missiles.

While the first hour or so shows some promise, the second half is hardly more than one preposterous escapade after another.

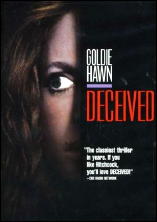

● DECEIVED. Touchstone/Buena Vista, 1991. Goldie Hawn, John Heard, Ashley Peldon, Robin Bartlett, Tom Irwin. Director: Damian Harris.

After five years of being happily married, a woman’s life is shattered when she discovers that her husband, now dead in an automobile accident, had been living a lie, under someone else’s name.

First a detective story, then a thriller, the story doesn’t quite seem to know where it’s headed, but it still packs a pretty good wallop. Goldie Hawn, in a straight role, is fine. (Lots of smudged mascara.)

COMMENT: There are two movie guides that I usually take a look at after seeing a movie. (Sometimes before.) The first, by Leonard Maltin, says, “Hawn’s attempt to play it straight is too derivative (to say nothing of incredible) to carry much clout.” The other, by Steven H. Scheuer, says, “Well-acted, especially by Hawn who’s rock solid…”

What does Maltin say about Melanie Griffith, in Shining Through? “Empathic performance by Griffith make(s) this palatable…” As for Scheuer: “Griffith is thoroughly unbelievable…”

These guys (or whoever’s writing for them) are obviously not seeing the same movies. (Are they on the same planet?)

[UPDATE] 06-06-10. According to my records, I actually wrote these reviews in September of 1993. Do I remember watching any of four? No, only the briefest of scenes come back to me from any of them.

I’m sure I still have these on video cassette, taped from the various premium movie channels we’d signed up for at the time. I’d be most anxious to give Gotham another try, if I could find it. It sounds like my kind of movie.

Maltin, of course, is still around. Scheuer stopped doing his movie guide in 1993, but he started in 1958, long before Maltin was old enough to vote. (He was eight at the time.) What the varying opinions demonstrate is that it never hurts to have two points of view on a movie. When two such devoted film critics as Siskel and Ebert can have diametrically opposed takes on one — many times over — it’s obvious that there can be no such thing as 100% agreement on how good (or bad) a movie is.