Wed 27 Feb 2019

Music I’m Listening To: CHUCK BERRY “You Never Can Tell.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening To[2] Comments

Wed 27 Feb 2019

Mon 25 Feb 2019

EDGE OF DOOM. Samuel Goldwyn, 1950. Released in Britain as Stronger Than Fear. Dana Andrews, Farley Granger, Joan Evans, Robert Keith, Paul Stewart, Mala Powers, Adele Jergens, Harold Vermilyea, Douglas Fowley and Ray Teal. Screenplay by Charles Brackett, Ben Hecht and Philip Yordan, from the novel by Leo Brady. Directed by Mark Robson.

A powerful and moving film noir despite some pasted-in tampering.

Farley Granger stars as Martin Lynn, a hard-working young man up against it: low-pay, a sick mother, and in love with a woman he can’t afford to marry. He has also carried a grudge against the Catholic Church ever since his father’s death by suicide years earlier.

Brackett, Hecht and Yordan sketch out his dilemma in a few pungent scenes as Martin frets over his mom, all but begs for a raise to move her to a healthier climate — and gets warmly refused. Director Robson handles it quickly, in a prosaic, sunlit style, contrasted with Granger’s politely controlled desperation, then moves to moodiness when Mom dies, leaving Martin shadowed in guilt—and determined to give her a fine funeral.

Things progress with a fine scene, written and played perfectly as Martin argues with the parish priest over what is clearly going to be a charity job. He’s up against Harold Verrmilyea, who had a good line in bent lawyers and venal medicos in those days. Here he’s cast as a burned-out priest who has lost the warmth and care Martin so badly needs. His dour refusal clashes with Martin’s growing angst and the young man’s well-bred manners visibly disintegrate when Vermilyea tosses him a buck for cab fare; more frustrated than angry, he clubs the priest to death with a heavy metal cross.

From here on, Edge of Doom moves solidly into noir territory, following Martin through a nightmare of suspicion, dread and guilt like a tortured Raskolnikov, harassed by hard cops (Robert Keith, Douglas Fowley and Ray Teal at their nastiest) befriended by Dana Andrews as Vermilyea’s compassionate successor, and tempted by sardonic Paul Stewart as a petty crook.

Edge is well played and poignantly written, but what struck me most was the steep visual style imparted by director Robson and photographer Harry Stradling. Together they fill the frame with vertical lines: tall buildings, high windows and elongated door frames, imparting a unique and evocative look to visually reinforce Edge’s themes of alienation and redemption.

Vertical lines serve to isolate Farley Granger’s character on the screen, and suggest oppression. But they also convey salvation. The great cathedrals and many other religious structures are traditionally designed with strong vertical lines, lifting the eye upward to the heavens. And so it is here, as the viewer sees on a subconscious level that Martin has a chance to rise from the mess of his life… and wonders if he’ll take it.

I’ll just add here that after some negative preview feedback — and, I suspect (but have no evidence for) pressure from the Church — producer Sam Goldwyn ordered Dana Andrews back for some additional scenes, showing him as a knowing but compassionate priest to further counterbalance Harold Vermilyea’s unsympathetic portrayal. They also added a prologue and epilogue to show us everything’s just fine, go home folks, and don’t worry, your Priest knows best.

And I won’t comment on that except to say it doesn’t spoil a gripping and eloquent film.

Sun 24 Feb 2019

Ken Nordine (April 13, 1920 – February 16, 2019) was the best spoken word jazz musician in the world, bar none:

Sun 24 Feb 2019

Hi Steve

Can you tell me about the two Thursday short stories/novelettes?

“Murder Has Girl Trouble†Mystery Book Magazine, Spring 1950

“The Corpse Walked Away†Two Complete Detective Books, January 1951

Are these stories different from the stories in the six novels? Or were they later expanded into two of the six novels?

Thank you,

Joe

Sun 24 Feb 2019

LESTER del REY, Editor – Best Science Fiction Stories of the Year: Second Annual Edition. E. P. Dutton, hardcover. 1973. Ace, paperback, December 1975.

#5. FREDERIK POHL & C. M. KORNBLUTH “The Meeting.” Short story. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, November 1972. First collected in Critical Mass by Frederik Pohl & C. M. Kornbluth (Bantam, paperback, 1977. Co-winner of the 1973 Hugo Award for Best Short Story.

Most science fiction readers of his era considered Cyril Kornbuth to be of the most gifted writers of them all — myself included — and considered his early death in 1958 at the age of 34 to be an absolute tragedy. He was known largely for his short fiction, starting at the age of 15, but before his death he wrote two novels on his own, plus several more in collaboration with others. “The Meeting” was a story that was finished by Frederik Pohl, working from notes Kornbluth left behind.

A married couple named the Vladeks have a young boy with severe developmental disabilities, and they have just moved to a new town to find a school specializing in students like him. Most of the story takes place during the first PTA meeting of the year, after which Mr. Vladek has a brief moment to talk to the principal about how nine-year-old Tommy is doing. His wife had to stay home, as Tommy has too many emotional issues to be left with a baby sitter.

What makes this a science fiction story comes very nearly at the end. There is a possibility that an experimental brain transplant procedure will solve Tommy’s problems, but a decision has to be made right away. The story ends with Mr. Vladek reaching for the telephone to tell the doctor what they’ve decided.

I don’t think anyone has had any doubt what that decision was going to be. This is a very sentimental, old-fashioned story — the portion that Kornbuth wrote was written in the 50s, after all, with Pohl finishing and polishing it up in 1972. It’s a good, well-structured story and was awarded a Hugo at the time, but I don’t believe it would today.

—

Previously from the del Rey anthology: ISAAC ASIMOV “The Greatest Asset.”

Sat 23 Feb 2019

LAWRENCE BLOCK – When the Sacred Ginmill Closes. Matt Scudder #6. Arbor House, hardcover, 1986. Charter, paperback, 1986. Jove, paperback, 1990.

I have just finished reading When the Sacred Ginmill Closes, in which Matt Scudder remembers a couple of ten-year-old cases that he worked on during his drinking days. I finished this in a rush of adrenalin produced by the excitement a perfect ending always produces in me.

Because, you see, is the less-traveled road on which I find myself these days, and it ha made all the difference. Oh, yes. All the difference.

The reflective, wry meditation on life lived and life changing (but perhaps, not all that much) is an appropriate ending for a novel of reflection on decade-old events. This inevitable conclusion (but inevitable only to a writer of Block’s gifts) is an example of perfect pitch in structure and tone.

It also reminds me of a moment in a recent episode of Inspector Morse (“Cherubims and Seraphims”) in which Morse’s niece, still caught up in the ecstasy of a drug-induced “perfect moment,” comments that life can never be again like that moment. She is short to kill herself, precipitating a search by Morse for answers to a death that has no answers.

I don’t think that Block necessarily had any sense that he had created something he could never achieve again. He’s continued to write, with great success, and probably never greater than in his Matt Scudder series, although this novel seemed to have a resonance that I don’t remember in any of the others. Let’s just say that my imperfect pitch, which certainly varies from one minute to the next, was at that moment in time in perfect tune with Block’s pitch.

However, I don’t feel that this is an experience I won’t have again, although the correspondent for it may be a musical composition, a film, a meal, a moment in a personal relationship. I come down from the highs, but the fall isn’t that intense, and the sense of loss isn’t that devastating. Oh, no. Not at all.

Also, if the ending to this particular Block novel seemed especially satisfying, it’s not profoundly apart from my usual reaction to Block’s work. My experience with mystery fiction is very limited these days, but Block has established in the Scudder series a consistently recognizable style that distinguishes it and him.

Fri 22 Feb 2019

I’ve just updated my website where you can find a list of mystery paperbacks I have for sale on Amazon. If you buy them directly from me, however, I can offer a 30% discount. This list is larger by a third than the one I linked to over a year ago now.

Included is a large collection of Black Lizard “noir” paperbacks from the 1980s. Authors such as David Goodis, Jim Thompson and Charles Willeford. Lots of cozies, too, and everything in between.

Thu 21 Feb 2019

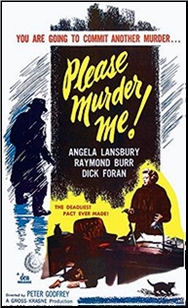

PLEASE MURDER ME!. Distributors Corporation of America, 1956. Angela Lansbury, Raymond Burr, Dick Foran, John Dehner, Lamont Johnson. Director: Peter Godfrey.

Before his role of a lifetime came along as TV’s Perry Mason, Raymond Burr did not have many leading roles in the movies, but here he is in Please Murder Me! as the second billed actor. I have no idea if this is the case, but it’s fun to speculate: If the people who were in charge of casting the role of Mason happened to have seen this movie, they would have said “He’s our guy!,” and signed him up on the spot.

He plays a lawyer in this one, if you hadn’t realized that already, but with a twist. His client is the woman he is in love with (Angela Lansbury), and she is charged with having killed her husband. She claims it was in self-defense, but the D.A. (John Dehner) is making an awfully good case that it was premeditated murder, when Burr’s character makes a confession that turns everything upside down.

It has already been established to the viewer that the dead man was Burr’s best friend, but the friendship has been permanently ruined when Burr tells the husband that he has fallen in love with his wife, and that he will be representing her in terms of a divorce.

This is not as complicated as perhaps I have made it sound, or maybe it is. It is the basis for a very good movie, one that I can definitely recommend. It really ought to have an official release.

While I could not discern any particular chemistry between Burr and Angela Lansbury, they are both well chosen for their respective roles. Before making this film Burr usually played villains, and if I say heavies, he was, but he had definitely slimmed down by the time he appeared in this one.

A late entry noir, and one defintely worth watching.

Thu 21 Feb 2019

HAMMOND INNES – Levkas Man. Collins, UK, hardcover, 1971. Knopf, US, hardcover, 1971. Avon, US, paperback, 1973. Ballantine, US, paperback, 1978.

For Paul Van der Voort, born Paul Scott, returning to his home in Amsterdam is filled with trepidation. His adopted father Dr. Pieter Van der Voort is not an easy man, and their relation is nothing if not frought.

…a young woman named Sonia Winters, whose brother is with Pieter on an expedition, berates him, and now Paul has returned to an empty house on the run and looking for a place to lay low only to find is estranged father is off on an expedition in the Greek islands following a trail of bones.

But all is not well with his father, a difficult and often times dark man, and an elderly teacher and colleague of Pieter’’s, his mentor Dr. Gilmore, fears for his sanity:

With a possible manslaughter or even murder hanging over him Paul is eager enough when he gets and offer to charter a boat, the Coromandel, and get out of the country, picking up a load of antiquities, and if the cargo isn’t entirely honest that’s no problem, and sailing from Malta to Turkey. But before he can leave another colleague of his fathers, Dr. Holroyd, shows up asking questions about his work and he discovers two shocking facts; his father has gone missing after what appears to be a violent attack on Sonia Winters brother in Greece, and Pieter may be his birth father and not just the man who adopted him when his mother and supposed father were killed on their farm in a Mau Man uprising in Kenya.

This is familiar country for Hammond Innes readers, a hero with a complex past, a journey to some place exotic, an older male figure the hero has a difficult relationship with, and the romance of expertise, in sailing, flying, surviving, or even the ancient past.

Once he reaches Greece however his inquiries about his father lead to complications. Pieter’s bizarre theories had meant the Russians were the only ones who would finance him, and though his Communism was merely convenient, and his theories had long since cost him his Russian ties, the police and secret police are far from happy about a former Russian sympathizer missing in their country especially as across the sea in North Africa tensions are rising. Paul finds himself under their watchful eye too, something less than helpful considering his present employment as a smuggler. Then to further complicate things a talkative Greek named Demetrios Kotiadis, claiming to be from some obscure ministry, starts asking questions and attaches himself to Paul and Sonia Winters shows up.

In any Hammond Innes novel there is a mystery to be solved, though it is seldom as simple as who killed whom. The hero, like the protagonist of a John Buchan novel, must go through a rigorous physical ordeal and emerge with new insight in order to solve that mystery, and here Paul Van der Voort must literally descend into the earth in a dangerous cave dive, the ancient past, his own history, an act of academic revenge, and the broken mind of Pieter to discover the truth, whatever the cost.

Hammond Innes’s reputation grew from the time of his earliest works in the shadow of the Second World War to a string of increasingly successful novels and film adaptations until his Wreck of the Mary Deare hit the bestseller list and became a hit film with Gary Cooper, Charlton Heston, and Richard Harris. His reputation continued to grow through the early sixties, until with The Strode Venturer, he not only penned a critical and successful novel but garnered reviews that compared him to Joseph Conrad. After that his novels became longer and more serious, but with no loss of the elements of adventure and suspense of the earlier works.

To some extent he outlived the era of his greatest success and not all of his later novels saw publication in this country, though books like Medusa and Isvik still received sterling reviews and read as well as any of his novels.

Today when you are reading the latest adventure thriller by a James Rollins, Clive Cussler, or whomever your favorite may be, you are reading in the tradition and footsteps of Hammond Innes (a former journalist who began writing thrillers during the war while serving in the British military as an anti-aircraft gunner), the most important and literate of that first generation of descendants of John Buchan like Geoffrey Household, Victor Canning, and Alistair MacLean.

To say he is first among equals is only a pale recognition of the impact and influence of his work in the genre. In 1953 when Ian Fleming penned Casino Royale, the first James Bond thriller, Innes was already selling 40,000 to 60,000 copies in hardcover and more in the Fontana paperback reprints in England according to Mike Ripley in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, his history of British thrillers from Bond to now.

Levkas Man is among many classics in a pantheon of works that includes Atlantic Fury, Gale Force, Campbell’s Kingdom, Blue Ice, The Angry Mountain, The Lonely Skier, White South, Air Bridge, The Killer Mine, The Doomed Oasis, The Land God Gave to Cain, Wreckers Must Breathe, The Big Footprint, The Golden Soak, and many more, but remains a favorite of mine for its dark classical themes, and as a fine novel of adventure and mystery.

Anyone who has never read Innes is in for a fine experience and a great deal of entertainment with a writer who brought to the adventure novel his seven league boots travel experiences, endless curiosity about the world and its environs, and the skills of a novelist and not just a storyteller.

Thu 21 Feb 2019

WEB OF DANGER. Republic Pictures, 1947, Adele Mara, Bill Kennedy, Damian O’Flynn, Richard Loo, Victor Sen Yung, Roy Barcroft. Director: Philip Ford.

In spite of the title, Web of Danger is not a crime film at all, and to tell you the truth, I can’t even tell you what the title means. In a small, rather slight degree, you might possibly call this a thriller, but since the danger caused a bridge-building crew by flooding far upriver, except for one specific scene, any suspense that’s conjured up is more in the mind of the viewer than from anything seen onscreen.

What it is, more than anything else, is a romantic drama, with the supervisor and foreman of the crew (Bill Kennedy and Damian O’Flynn) fighting it out (literally) over the hand of waitress Peg Mallory (Adele Mara) — as if she had no say in the matter.

Except for the accidental death of one of the crew members (see above), the story plays out in light and frothy fashion. Another exception is the rescue of the families whose homes are threatened by the levees about to break, which is perfunctory and anticlimactic. The part that’s light and frothy is well done, though!