Thu 5 Jan 2017

A Movie Review by Jonathan Lewis: THE MECHANIC (1972).

Posted by Steve under Crime Films , Reviews[6] Comments

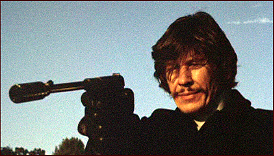

THE MECHANIC. United Artists, 1972. Charles Bronson, Jan-Michael Vincent, Keenan Wynn, Jill Ireland, Linda Ridgeway, Frank DeKova. Director: Michael Winner.

For the first sixteen minutes, there is no dialogue. None. Just a sequence in which we see Charles Bronson or, more accurately, a character portrayed by him, plan and execute an assassination of an older man living in a rundown Los Angeles hotel room. But there’s music accompanying the action, a score composed by Jerry Fielding. Unfortunately, the music overwhelms everything else, making it more obtrusive than artistic.

In many ways, this initial sequence is indicative of the film as a whole. It tries to be artistic and deep, but fails nearly on every level. And the overwhelming, out of place soundtrack doesn’t help matters, either.

Now, some may see this criticism as overly harsh. After all, what’s not to like about the pairing of Charles Bronson and a youthful Jan-Michael Vincent as a skilled hitman and his apprentice? Both are good actors for the genre, and there’s actually some personal chemistry between the two (an earlier version of the script apparently hinted at a forbidden romance between these two men who live outside societal norms).

But it’s not the acting, nor the script per se that makes this a rather dreary affair. It’s the fact that The Mechanic tries so hard, so very hard, to say something profound about what it must be like to be a hitman that it verges into self-parody. Bronson’s character, the titular mechanic, is a brooding, philosophical sort who lives alone in a giant Hollywood Hills home and who has a penchant for martial arts and seemingly little connections with other people, aside from a girlfriend portrayed by Bronson’s wife Jill Ireland. By trying too hard to make a statement, The Mechanic ends up saying very little.