A Review by MIKE TOONEY:

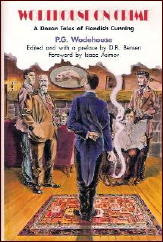

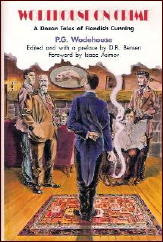

P. G. WODEHOUSE – Wodehouse on Crime: A Dozen Tales of Fiendish Cunning.

Ticknor & Fields, 1981. International Polygonics Library, hardcover/trade paperback: 1991. Editor: D. R. Bensen, with a foreword by Isaac Asimov.

P(elham) G(renville) Wodehouse–“English literature’s performing flea” (Sean O’Casey) and “the funniest guy I ever read” (H & R Block)–was a master of comedy. Now, tastes vary as to what constitutes humor — the eruption of Krakatoa still provokes a laugh in some circles — but P.G. Wodehouse (“Plum”, or just “You, there”) is generally acknowledged as the best-of-the-best.

Wodehouse on Crime collects twelve stories from Wodehouse’s massive output of over six decades of writing. At first blush, you wouldn’t associate innocuous P.G.W. with criminal intent, would you (and why are you blushing)? As the late Isaac Asimov asks in his foreword: “Can there be crime in the never-never-land of P.G.W. idyllatry? Certainly! The tales are saturated with it, and even that does not weaken our love … when one stops to think of it, there is rarely a story in the entire Wodehouse opera which doesn’t feature crime.”

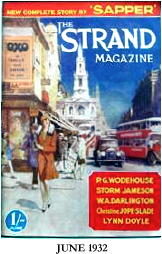

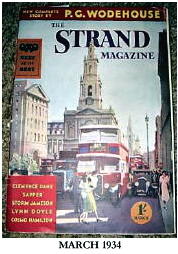

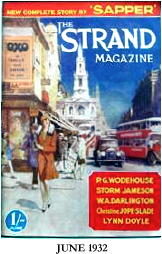

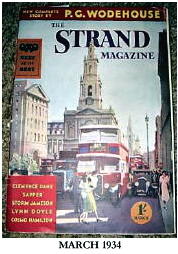

Editor D. R. Bensen adds that “… it would be impossible to present a full collection of those of P. G. Wodehouse’s stories which are concerned with crime. It would be a book of thousands of pages, with a spine about two and a half feet wide, which would make for awkward reading.” He also notes, tongue in cheek, the “baleful” influence that reading the Sherlock Holmes stories in the Strand had on the young and impressionable Plum.

However, be aware that if you’re seeking blood and gore and pick up Wodehouse on Crime, you’re in the wrong venue.

The first story in the collection, “Strychnine in the Soup,” is typically criminous Wodehouse. Plum’s Underwood portable here dispenses a lively story — a gentle spoof of Golden Age Mystery conventions — centering on Mr. Mulliner’s nephew Cyril, a diffident chap who encounters Miss Amelia Bassett at a play. After an awkward introduction — she grabs his leg — Cyril speaks first:

“You are evidently fond of mystery plays.”

“I love them.”

“So do I. And mystery novels?”

“Oh, yes!”

“Have you read Blood on the Bannisters?”

“Oh, YES! I thought it was much better than Severed Throats.”

“So did I,” said Cyril. “Much better. Brighter murders, subtler detectives, crisper clues … better in every way.”

Then, says the author, “The twin souls gazed into each other’s eyes. There is no surer foundation for a beautiful friendship than a mutual taste in literature.”

A little later, Amelia asks apropos of nothing: “Tell me … if you were a millionaire, would you rather be stabbed in the back with a paper-knife or found dead without a mark on you, staring with blank eyes at some appalling sight?” — a question we’ve all asked ourselves, I’m sure; but before Cyril can answer, in walks Amelia’s formidable mother …. but read “Strychnine in the Soup” for yourself, and the eleven other stories, too.

As with H. P. Lovecraft’s fiction, take P.G.W. in small doses for best results — you wouldn’t want to overdo it — in between, say, the disappearance of Mr. Davenheim’s moustache and the murder of Mrs. Twisby-Axleby’s trained albatross in that blood-drenched Golden Age mystery you’re currently reading. (Oh, and by the way, Mr. Mulliner’s solution to The Murglow Manor Mystery, mentioned in passing, is intricate … and completely loopy.)

To die an embittered misanthrope was the sad fate of too many of our great humorists — Mark Twain, S. J. Perelman, Soren Kierkegaard — but not so with P. G. Wodehouse: He reportedly kept a stiff upper lipper to the end, remaining at his post as the fort was being overrun by mutinous Sepoys and seditious Polyglots, a feather duster in one hand and his Underwood portable in the other.

That Plum: What a guy!

Contents:

“Strychnine in the Soup” (1932)

“The Crime Wave at Blandings” (1937)

“Ukridge Starts a Bank Account” (1967; reprinted in EQMM in 1982)

“The Purity of the Turf” (1923)

“The Smile That Wins” (1931)

“The Purification of Rodney Spelvin” (1927)

“Without the Option” (1927)

“The Romance of a Bulb-Squeezer” (1928)

“Aunt Agatha Takes the Count” (1923)

“The Fiery Wooing of Mordred” (1936)

“Ukridge’s Accident Syndicate” (1926)

“Indiscretions of Archie” (1921)

Addendum:

“I seem to keep finding, or I keep seeming to find, trace elements of Doyle in the Wodehouse formulations. I sense a distinct similarity, in patterns and rhythms, between the adventures of Jeeves as recorded by Bertie Wooster and the adventures of Sherlock Holmes as recorded by Dr. Watson ….”

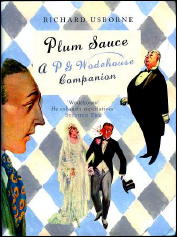

So states Richard Usborne in his Plum Sauce: A P. G. Wodehouse Companion (2002). He goes on: “The high incidence of crime in the Wodehouse farces, especially the Bertie/Jeeves ones, may be an echo of the Sherlock Holmes stories, too — blackmail, theft, revolver shots in the night (Something Fresh), airgun shots by day (‘The Crime Wave at Blandings’), butlers in dressing-gowns, people climbing in at bedroom windows, people dropping out of bedroom windows, people hiding in bedroom cupboards, the searching of bedrooms for missing manuscripts, cow-creamers and pigs. I am not accusing Wodehouse of having concocted his stories deliberately on Doyle’s lines; I am saying that, of all the authors to whom Wodehouse’s debt shows itself, Doyle is second only to W. S. Gilbert. And Wodehouse would gladly have acknowledged both debts.”

That bears repeating: “… Doyle is second only to W. S. Gilbert” as an influence on the foremost humorist of the twentieth century.

Wodehouse admitted as much to a biographer: he “recalled the excitement of waiting for new issues of The Strand Magazine on Dulwich station” containing the latest Holmes adventures.

Another of Wodehouse’s characters was Psmith (pronounced “smith”). Usborne writes that one of the “strongest influences in the rhythms and locutions of the Psmith language was Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories … Wodehouse’s first major conversational parodist, Psmith, is constantly echoing Sherlock Holmes (indeed, the Holmes Valley of Fear influence probably to some extent suggested the plot of Psmith Journalist). Psmith has verbal ‘lifts’ from Sherlock Holmes, with direct quotations of words and copying of manner”; and Usborne produces several examples from the Psmiths and the Jeeves and Woosters.