WRITING NERO WOLFE,

by Lee Goldberg.

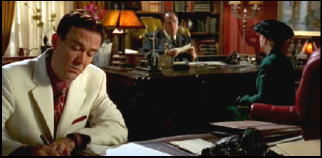

INT. BROWNSTONE — WOLFE’S OFFICE — DAY

Archie sits at his desk, OILING HIS TWO MARLEY .38s. As we hear his voice-over, he switches to OILING HIS TYPEWRITER with the SAME OIL.

ARCHIE’S VOICE

Nero Wolfe is a creature of habit. Every morning, from nine until eleven, he tends his 10,000 orchids and I, Archie Goodwin, his confidential secretary and legman extraordinaire, tend to business. And since there wasn’t any business to tend to, I was preparing for action — if and when it ever came.

The PHONE RINGS. He answers it.

I can’t tell you how much pleasure it gave me to write those words, the opening scene of the A&E adaptation of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe novel “Champagne for One.”

For one thing, I’ve been a fan of Nero Wolfe since I was a kid. The Brownstone on West 35th Street where Nero Wolfe and Archie Goodwin live and work in New York City was as real to me as my family’s suburban tract home in Walnut Creek, California. I read each and every book, reveling in Archie’s amiable narration, his lively banter with Nero Wolfe, and Wolfe’s wonderfully verbose and brilliant speeches. While I may have been underwhelmed, even as a teenager, by Stout’s lazy plotting, I loved the language and, most of all, the relationship between Wolfe and Archie. I never dreamed I’d have a chance to write those characters myself. And, in the case of that opening, to write new words in their voices, at least as I’ve always heard them.

It was a screenwriting assignment unlike any other that my writing partner, William Rabkin, and I had ever been involved with. Because “Nero Wolfe,” starring Maury Chaykin as Wolfe and Timothy Hutton as Archie, was unlike any other series on television. It was, as far as I know, the first TV series without a single original script — each and every episode was based on a Rex Stout novel, novella, or short story. That’s not to say there wasn’t original writing involved, but it was Stout who did all the hard work.

Everyone who wrote for “Nero Wolfe” was collaborating with Rex Stout. The mandate from executive producers Michael Jaffe and Timothy Hutton (who also directed episodes) was to “do the books,” even if that meant violating some of the hard-and-fast rules of screenwriting.

Your typical hour-long teleplay follows what’s known as a four-act structure. Whether it’s an episode of “The West Wing” or “CSI,” the formula is essentially the same. But “Nero Wolfe” ignored the formula, forgoing the traditional mini-cliffhangers and plot-reversals that precede the commercial breaks.

Instead, we stuck to the structure of the book, replicating as closely as possible the experience of reading a Rex Stout novel (which, sadly, few viewers under the age of 50 have ever done).

In the highly competitive world of primetime network television, and in an era of “MTV”-style editing, it helped “Nero Wolfe” stand apart (and, perhaps, sealed its doom). “Nero Wolfe” required the writer to turn off most of his professional instincts and, instead, put all his trust in the material — which was a whole lot easier if you were already a Nero Wolfe fan.

“It’s amazing how many writers got it wrong,” says Sharon Elizabeth Doyle, who was head writer for “Nero Wolfe.” “I mean very good writers, too. Either you get it or you don’t. It’s so important to have the relationships right, and the tone of the relationships right, to get that it’s about the language and not the story. The characters in these books aren’t modern human beings. You have to believe in the characters and respect the formality of the way they are characterized.”

That doesn’t mean writers for the show simply transcribed the book into script form. It can’t be done. There’s no getting past that a novel and a TV series are two distinct, and very different, mediums. The writer’s job on “Nero Wolfe” was to adapt Rex Stout’s stories into scripts that could be produced on a certain budget over a seven-day schedule on a particular number of sets and locations. Beyond that, the writer had to re-tell Stout’s story in the idiom of television. By that, I mean the story had to be shown not told, through actions rather than speech, which isn’t easy when you’re working with mysteries written in first-person that are mostly about a bunch of people sitting in an office and talking. And talking. And talking. It’s very entertaining to read it, but can be deadly dull if you have to watch it.

Our first step in the adaptation process was the most fun — we’d sit down and read the book for pure pleasure, to get the feel and shape of the story (I couldn’t believe someone was actually paying me to read a book that I loved!)

After that, the real work started. We’d sit at the laptop and briefly jot down notes on the key emotional moments of the story, the major plots points, the essential clues, and most importantly, whatever the central conflict was between Wolfe and Archie. We’d also make notes of an obvious plot problems (and there were many). Once we were done with that, we were ready to read the book again, only not as readers but as literary construction workers who had to figure out how to take the structure apart and rebuild it again in a different medium.

We”d go through the book page-by-page, highlighting essential dialogue while writing a scene-by-scene outline on the computer as went along. We used the outline, combined with our previous notes, to get a firm grasp on the story, to see what scenes had to be pared down, combined or removed. Within scenes, we looked for ways the dialogue could be tightened, simplified or re-choreographed to add more momentum, energy and movement to the episode. And we’d do all this while keeping one thought constantly in our minds: stick as closely to the books as you can.

More often than not, that meant loyalty to the dialogue rather than to the structure of the plot or the order, locations, or choreography of the scenes. Because the first thing we discovered as we took apart Stout’s stories and put them back together again was how thin and clumsily plotted the mysteries are — a weakness that seems to be more easily hidden in prose than it can be on camera (which is one reason plots are so often reworked in the movie versions of your favorite mysteries).

“Television does seem to make the plot problems more glaring. The Nero Wolfe mysteries, generally, are very weak,” says novelist Stuart Kaminsky, who adapted the novella “Immune to Murder” into an episode. “Wolfe seldom does anything brilliant. We are simply told he is brilliant and are convinced by his manipulation of people and language. His is a great act.”

Any avid reader of the Stout books soon discovers that there are three ways Wolfe will solve a mystery:

a) Wolfe either calls, mails, or in some other way contacts all the suspects and accuses each one of being the murderer, then waits for one of them to expose him or herself by either trying to steal or retrieve a key piece of evidence — or trying to kill Archie, Wolfe, or some other person Wolfe has set up as bait.

b) Wolfe sends his operative Saul or Orrie to retrieve some piece of evidence that is with-held from Archie (and, by extension, all of us) and revealed in the finale to expose the killer.

c) Wolfe uses actual deduction.

The challenge in adapting the Nero Wolfe stories for television was obscuring those plot problems by playing up the character conflicts and cherry-picking the best lines from Wolfe’s many speeches. The plots became secondary to the relationships and the uniqueness of the language. The vocabulary was never dumbed down or simplified for the TV audience, which is why the series felt so much like the books.

“There is a pleasure in Wolfe’s speeches, what we call the arias,” says Doyle. “Wolfe has lots of them, the trick is isolating that one aria you can’t live without.”

In the novel “Too Many Clients,” which Doyle adapted for the show, there was one Nero Wolfe speech that she knew had to be in the episode:

“A modern satyr is part man, part pig, part jack-ass. He hasn’t even the charm of the roguish; he doesn’t lean gracefully against a tree with flute in hand. The only quality he has preserved from his Attic ancestors is his lust, and he gratifies it in the dark corners of other men’s beds or hotel rooms, not in the shade of an olive tree on a sunny hillside. The preposterous bower of carnality you have described is a sorry makeshift, but at least Mr. Yeager tried. A pig and a jack-ass yes, but the flute strain was in him too, as it once was in me, in my youth. No doubt he deserved to die, but I would welcome a sufficient inducement to expose his killer.”

Where else on television do you find a character who talks like that? No where. Not before “Nero Wolfe,” and not now that it has been cancelled.

“There is one thing we did that nobody else is doing. We played with the language and had a good time doing it,” Doyle says. “Most TV language is very minimalist.”

She’s right. When was the last time you heard a TV character use satyr and bower in casual conversation? I’m not surprised “Nero Wolfe” was canceled. Perhaps the creative choices that were made, while respecting the material, were wrong for TV. Not because audiences are stupid, but because television is, ultimately, not a book, and certainly not one written in the 1940s. By design, the show had a dated feel, one that may have alienated all but the oldest viewers and the most avid Wolfe fans.

That said, and with my obvious biases showing, I think the series, and especially the performances of Maury Chaykin and Timothy Hutton, will be recognized as the definitive dramatic interpretation of “Nero Wolfe,” the one any future movie or TV incarnations will be measured against. And I was honored to be a part of it.

Lee Goldberg was nominated for an Edgar Award by the Mystery Writers of America for his work on “Nero Wolfe.” This article first appeared in Mystery Scene magazine and is reprinted with the author’s permission.