Tue 21 Jan 2020

Time for my semiannual mystery hardcover and paperback sale. The prices on the sites below are those as offered on Amazon. If ordered from me directly, take discounts of 10 to 40 percent.

Tue 21 Jan 2020

Time for my semiannual mystery hardcover and paperback sale. The prices on the sites below are those as offered on Amazon. If ordered from me directly, take discounts of 10 to 40 percent.

Tue 21 Jan 2020

THE SWEENEY “Ringer.” ITV, Thames Television. 02 January 1975 (Season 1, Episode 1). John Thaw, Dennis Waterman, Garfield Morgan. Guest Cast: Ian Hendry, Brian Blessed, Jill Townsend. Writers: Trevor Preston, Ian Kennedy Martin. Director: Terry Green.

“The Sweeney” is Cockney slang for London’s Flying Squad, a branch of the Metropolitan Police (short for Sweeney Todd, a rhyming version of ‘Flying Squad’). It was on British TV for four seasons, followed by three theatrical movies. John Thaw (Inspector Morse) played Detective Inspector Jack Regan, while Dennis Waterman (New Tricks) was his second in command, Detective Sergeant George Carter.

I’m not sure why this first episode is titled “Ringer,” but it’s a good one. A car that Regan has borrowed from a sleep-in girl friend to do some surveillance work for the day is stolen, along with his camera and several photos he’d already taken. (He had, unfortunately left the car unlocked.)

The brighter of the two thieves has the clever idea of selling the photos to the subject of Regan’s observations, a highly-connected gangster who has some sort of hush-hush operation about the get underway. and he doesn’t fancy the Flying Squad having any idea that something is going on.

The resulting story has both an abundance of close-up dialogue as well as intense action — not of cars roaring up and down city streets and isolated country roads, as most American cop and PI shows were wont to do — but intense person-on-person action, which is down to earth and certainly a whole lot more, well, personal.

It is also remarkable how well-cast and effective the actors in this 60 minute play are, every single one of them, big parts or small. I wish that my American ears were more used to British accents (no subtitles on the video I saw), but I picked up more than enough to tell you that I really enjoyed this one.

Mon 20 Jan 2020

Sarah Andrews, her husband Damon and son Duncan died in a plane crash that occurred last July 24th. She was the author of eleven mystery novels featuring forensic geologist Em Hansen. Andrews herself had a BA in geology and an MS in Earth Resources from Colorado State University.

The Em Hansen series —

1. Tensleep (1994)

2. A Fall in Denver (1995)

3. Mother Nature (1997)

4. Only Flesh and Bones (1998)

5. Bone Hunter (1999)

6. An Eye for Gold (2000)

7. Fault Line (2002)

8. Killer Dust (2003)

9. Earth Colors (2004)

10. Dead Dry (2005)

11. Rock Bottom (2012)

Plus one additional book in what may have been intended to be the start of another series, this one featuring Val Walker, a master’s student in geology:

In Cold Pursuit (2007)

Mon 20 Jan 2020

PHILIP DePOY – Sidewalk Saint. CPS officer Foggy Moscowitz #4. Severn House, hardcover, December 2019. Setting: Florida.

First Sentence: It doesn’t take long to wake up when there’s a gun in your face.

Nelson Roan demands that Child Protective Services agent Foggy Moscowitz find his 11-year-old daughter Etta. He’s not the only one looking for her. It seems Etta has perfect memory and knows something she shouldn’t. How do you convince a bunch of bad guys that not even Etta doesn’t know what that is? It’s up to Foggy to find her and keep her safe until he can figure out how to neutralize the danger to Etta permanently.

Talk about an effective hook. This is not a book where you read a paragraph for a quick try, planning to sit down with it later. This is a book where you read the first sentence and keep reading. The case is intriguing. One wants to know where it’s going, and the plot twists start very early on.

DePoy not only captures your attention, but his unique descriptions bring the characters to life– “His skin was grey, and his eyes were the saddest song you ever heard, times ten.” His use of language is wonderful– “The camp seemed to have a life of its own. It wasn’t just the leftover smells, cook fires, swamp herbs and tobacco. It was like an eerie echo was still reverberating around the concrete walls. Like old conversations were still hanging in the air. Like ghosts were wandering free.”

As for Foggy, DePoy informs readers of who he is, his background, and how he got where he is and eventually, the meaning of the book’s title. Foggy’s philosophy may make one think– “I was always a big believer in is. Not should be, or ought to. Is. That’s very powerful, because it is the only reality. Whatever it is you were doing, that was the only thing that truly existed. Everything else was a fantasy.”

Foggy also makes an insightful self-observation– “To me that was the weird thing about having a reputation as a good guy. Too many people expected me to be good. Which I wasn’t especially. I was just a guy trying to make up for what he’d done wrong.” A nice explanation of the title helps one to understand Foggy better.

DePoy’s characters, on both sides of the law, are far from ordinary, which is a large part of the appeal. They are quirky, interesting, capable and surprising. His children are refreshingly smart, capable, and astute– “You know you’re too smart for your own good, right?’ I suggested. ‘Oh, yes,’ she said. That’s my main problem.” He really does write some of the best dialogue.

There is a nice element of mysticism. It doesn’t overwhelm the plot, but instead, it adds another interesting layer too it. In a way, it balances the bad stuff. The turns this story takes are more dizzying than a state fair teacup ride. Not just any author can come up with a plot point to destroy a mobster and his business via a phone call

Sidewalk Saint is a fun, twisty book filled with quirky, unique characters. There’s violence, but minimal on-page death, but the story also gives one plenty of ideas to consider.

Rating: Good Plus.

The Foggy Moskowitz series —

1. Cold Florida (2015)

2. Three Shot Burst (2016)

3. Icepick (2018)

4. Sidewalk Saint (2019)

Sun 19 Jan 2020

ZZ Top is a classic blues rock band that was first formed in 1969, but since 1970 the group has consisted of vocalist/guitarist Billy Gibbons, bassist/vocalist Dusty Hill, and drummer Frank Beard. That’s 50 years of performing together. Not many bands can say that!

Sun 19 Jan 2020

THE GREAT HOTEL MURDER. 1935). Edmund Lowe, Victor McLaglen, Rosemary Ames, Mary Carlisle, Henry O’Neill, C. Henry Gordon, John Wray, Madge Bellamy. Based on the novel by Vincent Starrett. Director: Eugene Forde.

Edmond Lowe, the star of two mystery movies recently reviewed here by David Vineyard, plays detective once again in The Grand Hotel Murder. An amateur detective, I should add. In real life he’s a writer of mystery novels, but also one who’s able to make Sherlock Holmes-type deductions just by careful observation of a young girl sitting impatiently in a hotel lobby.

His counterpart in this film is a somewhat slower in the wits department hotel detective, played in good humorous fashion by Victor McLaglen. (This is not the only time that he and Lowe teamed up together, beginning with their Flagg and Quirt series, the first of which was What Price Glory?, a silent film released in 1926, with three or maybe four sequels.)

The dead man whose murder is reflected in the title of the film was a gentlemen who finagled the young girl’s uncle into switching rooms with him over night. The question immediately of course is, who was the actual target?

Lowe and McLaughlin do their best to one-up the other throughout the movie, and it comes as no surprise (without revealing anything) that it is Lowe’s character who almost always come out on top, to good comedic effect, as well as being a fairly decent detective story.

The opening scenes follow Vincent Starrett’s novel fairly closely, but from that point on, the two story lines diverge significantly. I remember reading somewhere, a reference now lost, that after seeing the movie himself, Starrett confessed that the killer’s identity surprised him as much as anyone else.

In conclusion, I will say that it surprised me too, even though I didn’t write the book.

Sat 18 Jan 2020

PAUL CONNOLLY – Tears Are For Angels. Black Gat #24 / Stark Huse Press, paperback, February 2020. First published as Gold Medal #224, paperback original, 1952. Cover art by Barye Phillips.

I’m sure that back in 1952 no one knew that Paul Connolly was a pen name, much less for someone by the name of Tom Wicker. And even if they had, how would they have known what Tom Wicker was going to go on to be, or in other words a highly respected and long-time reporter for the New York Times? But that’s what happened, and even more than that, in terms of the book itself, this one’s a good one.

And it’s also a prime example of what we collectors of old 1950s Gold Medal paperbacks point to when we say that Gold Medal was the greatest publisher of hardboiled/noir pulp fiction of all time, bar none.

The plot is both a complicated one, and a simple one. I’ll try to summarize it, though, in the latter vein. At the beginning of the book one-armed Harry London is living the life of a drunken, unshaven (not to mention unbathed) recluse, regretting the night he found his wife Lucy, the love of his life, in bed with another man.

In what followed, Lucy ended up dead, Harry lost an arm, and the other man? He got away. Now, several years later,along comes Jean, a friend of Lucy’s, wondering what had happened to her. What also happens is that Jean awakens something in Harry, and together they find themselves planning, if not to change the past, then to avenge it.

Their scheme is too complicated to work, but is it? Hatred burns in both them, and though a fake marriage is part of heir plan, neither of them will admit what the reader will know at once, and I’ll wager you do too, right now, without my saying another word.

But make no bones about it. Fate and a sense of doom have taken over them, and part of the fascination in reading on to the end is to discover if they can ever find their way out of the morass of conflicting emotions they find themselves in. It is not at all certain that they will, and may I suggest to you that they do

This is true noir, in other words, and this is a book that’s well enough written that once read, you will not easily forget it. Guaranteed and recommended.

Books by Paul Connolly —

Get Out of Town. Gold Medal 1951

Tears Are for Angels. Gold Medal 1952

So Fair, So Evil. Gold Medal 1955

Sat 18 Jan 2020

DICTE “Personskade (Personal), Part One.” Miso Film/TV2 Danmark, 07 January 2013. 60m. Iben Hjejle (Dicte Svendsen), Lars Brygmann (John Wagner), Emilie Kruse, Dar Salim, Simon Krogh Stenspil. Based on characters in novels by Elsebeth Egholm. Director: Jannik Johansen.

The ending of this one really caught me by surprise. Not because it was a shocker or based on a twist that I didn’t see coming. No it’s a lot simpler than that, and I feel stupid by even bringing it up. I didn’t realize that the story was part one of two, and I wasn’t even watching the clock. Ha! on me.

But one thing’s for sure. As soon as I get done typing this, I’m going to go watch Part Two.

This is the first episode of three seasons of Dicte, consisting of five two-parters per season, or 30 episodes in all. (I probably could have left you to do the math). Dicte Svendsen, recently divorced, is a news reporter who has just moved back to her home town of Aarhus with her daughter Rose, a young lady who appears to be in the equivalent of high school in the US. She is certainly young enough that her mother has to keep a close eye on the friends she is making.

It is by accident, though, that Dicte begins her first brush with a big story. A young girl is found dead, murdered, her body mutilated in such a way that a botched Caesarean must have taken place, and Dicte is the first on the scene.

Photos taken by the news photographer accompanying her are the bargaining chips she needs for John Wagner, the police officer in charge of the case, to allow her to keep investigating the story.

There is a theme here. When younger, Dicte was forced by her parents to give up a child a soon as he was born; now Dicte has problems dealing with her daughter’s new male friend. And the girl who died, probably a prostitute, has forcibly lost the surrogate child she was carrying.

To me, actress Iben Hjejle seems too young to have such a long history behind her, but maybe that’s because I am much older than she. The story is a little darker than Death in Paradise, to take a recent example reviewed here, or The Invisibles, to pick another, but not not as ,much as Dexter or Hannibal here in the US. There will be Much more TV on my agenda this year, I can see that now.

Fri 17 Jan 2020

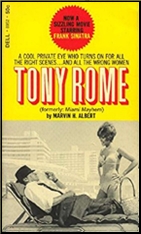

TONY ROME. Fox, 1967. Frank Sinatra, Jill St John, Richard Conte, Gena Rowlands, Simon Oakland, Sue Lyon, Robert J Wilke, Rocky Graziano, Michael Romanoff and Shecky Greene. Screenplay by Richard Breen, based on the novel Miami Mayhem, by Anthony Rome (Pocket Books, 1960); later published by Dell (1967) as Tony Rome, under the author’s true name Marvin H. Albert. Directed by Gordon Douglas.

Required viewing.

The success of Harper (1966) sparked a modest revival of movie PIs, giving us Gunn (1967), PJ (1968) and Tony Rome to liven up the waning decade – not that the 60s needed much enlivening, thank you, but this was a worthy entry in the cycle, a film that flaunts its vulgarity with commendable energy.

Gordon Douglas’s punchy direction helps a lot, and Sinatra approaches the tough PI part… well, not seriously, but he doesn’t phone it in either, and he’s supported by a cast that moves easily through the gaudy squalor. I particularly liked Robert J. Wilke as Rome’s ex-cop ex-partner:

TURPIN: “I saved your life.â€

ROME: “I could square that with a stick of chewing gum.â€

Even Jill St John seems at ease as a much-divorced lady of what we used to call “easy virtue†who makes her entrance walking toward Sinatra as Sue Lyon hisses “SLUT!â€

FRANK: “Well now that we’ve been introduced…”

JILL: “Slut’s just my nick name.”

The story involves… well, I never could get it straight. Something about missing diamonds, shady jewelers, hired killers and unhappy wives. TONY ROME also takes advantage of the loosened restrictions of its time to bring in a few gay characters, all them treated shabbily; standards had grown looser but not matured.

This aside, Tony Rome offers everything a fan of the genre could ask: clever dialogue, brutal fight scenes and sudden shoot-outs (director Douglas’s signature bit was a guy returning fire even as he visibly shudders under the impact of his opponent’s bullets) and an attitude at once flip and gritty. And it all leads to a resolution that recalls the weary disenchantment of Double Indemnity.

Don’t mistake me. Tony Rome is miles away from Wilder’s classic by just about any standard. But its trashy attitude is just perfect for the PI film of a troubled time.

Thu 16 Jan 2020

SARA PARETSKY – Bitter Medicine. V. I. Warshawski #4. Morrow, hardcover, 1987. Ballantine, paperback, 1988.

A sixteen year old Hispanic girl dies while trying to deliver her baby in the emergency room of a wealthy suburban Chicago hospital, and PI V. I. Warshawski finds she has quite a case on her hands. A malpractice suit follows, and a doctor is the next to die.

Slowly the pieces of he puzzle are fit together. Warshawski is a woman who sweats, cares about her friends, and frets when she makes an error in judgment — and she makes a couple of beauties here. All it does is keep her in the same class as Marlowe and Spade.

PostScript: Don’t take this to mean that I think Paretsky is in the same class as Chandler and Hammett as a writer, however. I meant what I said, and I don’t mean what I didn’t say.