Fri 23 Feb 2018

Reviewed by Jonathan Lewis – LEON M. URIS – The Angry Hills.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[5] Comments

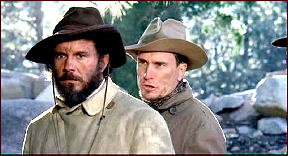

LEON M. URIS – The Angry Hills. Random House, hardcover, 1955. Signet S-1365, paperback, 1956. Several other reprint editions. Film: MGM, 1959 (with Robert Mitchum, directed by Robert Aldrich).

As much part of the men’s adventure fiction genre as it is a spy novel, Leon Uris’s The Angry Hills offers up a panoply of thrilling and romantic scenarios for the reader. Written in an accessible style with little to no literary flair, the novel starts off strong only to peter out midway through. It’s a shame that the work never quite follows through on his promising opening in which developed his protagonist with seemingly great attention to detail.

Michael Morrison is an American writer from San Francisco who finds himself in Greece around the time of the Nazi invasion during the Second World War. A recent widower, he’s in Athens and is saddened when he looks around city and wishes that his wife were there to experience it with him. Soon enough, he becomes embroiled in an international game of intrigue when he is handed a list of names that is vital to the Greek resistance movement and the Allied effort to assist them in the fight against Nazism. Morrison first impersonates a British officer, then a New Zealander. How he would accomplish with an American accent is not remotely plausible and Uris’s attempt to deal with it convincingly falls flat.

The novel continues to pick up its frenetic, adventuresome pace until Morrison gets injured. He finds himself being nursed back to health by a Greek peasant girl. This is where the work begins its slow decline into formula. Enter not only the girl and her hearty Greek villager father who wishes to marry her off, but also a German officer villain with a riding crop who reads like he was written into the novel by Central Casting, and his sleazy overweight Greek collaborator friend.

There’s some good material in The Angry Hills, including Uris’s depiction of the volunteer Palestinian (Jewish) Brigade in the British Expeditionary Force who fought on the Allied side in Greece. Morrison is a character that readers will find themselves rooting for, even if he cannot be completely distinguished from similar ordinary men in adventure fiction who find themselves swept up in a whirlwind of war and women. But the novel as a whole never really distinguishes itself. It’s a light read with little depth and one that gets increasingly predictable as it nears a conclusion that feels like it came straight from a Republic Pictures serial.