Wed 31 Aug 2016

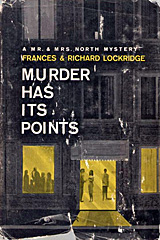

Mystery Review: FRANCES & RICHARD LOCKRIDGE – Murder Has Its Points.

Posted by Steve under Reviews[3] Comments

FRANCES & RICHARD LOCKRIDGE – Murder Has Its Points. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1961. Pocket, paperback, April 1984. (On the latter the two authors’ names are reversed.)

This one begins at a cocktail party at a Manhattan hotel and ends with an attempted shooting by a desperate killer in a suburban Connecticut mansion. Of the two settings, I liked the first one best. The party is hosted by book publisher Jerry North and is filled with all kinds of agents, movie reps, authors and literary critics, playwrights and actors. Following Pam North’s thoughts and broken bits of conversation as she tries to make her way across the room is worth the price of admission in itself:

Toward the end of the party, one literary giant of an author comes storming up to another (but one who is more of a poseur), demanding satisfaction for a crushing review written by the latter of the former’s latest book. A short exhibition of fisticuffs breaks out. Before the day is out, the latter author is dead, shot in the head by what appears to be a random sniper, or so assume the police, since a series of similar events has been happening in recent days. It is New York City, after all.

But such, as it turns out, and not at all surprisingly to the reader, is not the case. It also turns out that the dead man had a entire host of enemies and therefore would-be killers, all of whom seem to have been on the scene or nearby. The ending (see above) is both rather prosaic and muddled — but not so badly as it seems at first — at least in comparison to this brilliantly choreographed opening.

Captain Bill Weigand of the Manhattan homicide squad is, as ever, on hand to help solve the case, but of course it is Pamela North who is the middle of everything at all times, including the attempted shooting up in suburban Connecticut.

The title of this novels comes from a bit of random conversation at the cocktail party. It is Pam’s answer to the question, why does her husband publish detective novels?