THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by Monte Herridge

#16. Detective X. Crook, by J. Jefferson Farjeon.

Detective X. Crook is another of the many series characters in Flynn’s/Detective Fiction Weekly. He appeared in 57 stories from 1925-29, all written by the English detective story novelist J(oseph) Jefferson Farjeon (June 4, 1883-June 6, 1955).

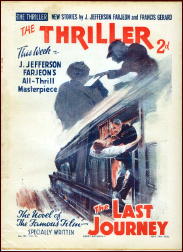

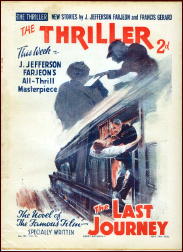

Farjeon was a descendant of Thomas Jefferson, and was named after his maternal grandfather, Joseph Jefferson, a well-known actor of the time. One of his works, “Number 17â€, was originally a stage played that was filmed twice: once in 1928 and the second time in 1932 by Hitchcock. Three other films were also based upon some of his approximately eighty books. He also wrote a novelisation of the thriller movie The Last Journey. This was published in No. 398, July 18, 1936 issue of The Thriller, a weekly fiction magazine published in the UK.

His sister was Eleanor Farjeon, author of works for children. One brother was Herbert Farjeon, a playwright. Another brother was Harry Farjeon, a musician. Their father was novelist Benjamin Farjeon (1838-1903). It is clear that this was a literary family, and to get an idea of the author’s first twenty years see the book written by sister Eleanor: Portrait of a Family (1936) in the US, A Nursery in the Nineties (1935) in the UK. It gives a good insight into their younger years up to about the age of twenty. As teenagers, Jefferson and his brother Herbert edited and wrote a very small circulation magazine, undoubtedly giving them some experience they would use in later years.

The X. Crook stories that appeared in Flynn’s/DFW is an average series that seems to have been popular enough to have run into quite a few tales. The mysteries in the stories are often simple and tame, and their solution by X. Crook is mostly a bit too plodding. However, there are some stories that stand out for their exceptions to the above, and many of these are later in the series.

From what I can determine from very little information, most or all of the stories had previously appeared in the magazines Pictorial Magazine and Pictorial Weekly in Britain. “The Fourth Attempt†appeared in the British magazine Pictorial Magazine, August 28, 1926 issue. It then appeared in the July 9, 1927 issue of Flynn’s.

The main character is something of a two dimensional personality, and really very little is made known about him throughout the series. In fact, his blandness and personality are such that he tends to blend into the background. From his name, it is clear that he is not using his real name. Crook is a reformed criminal who, upon release from prison for some unnamed offense, changes his name and takes up the profession of private detective. He means to start a new life and cut off ties from the old law-breaking ways.

In a number of stories he meets up with former acquaintances, but his real name is not mentioned. He has good relations with the police, after proving his true reformation. His viewpoint in his new life is pointed out in one of the stories: “My second duty is to my clients, my first to justice and humanity.†And “Theoretically they are the same,†he answered, “but as we practice them they sometimes differ…†(Elsie Cuts Both Ways).

Later in the story he tells a criminal he is trying to reform: “. . . and my life’s work is to try and help those who, like myself, are trying to wipe out their old mistakes.†He tends to make optimistic sayings to criminals, trying to convert them. When speaking of time in prison, he states: “There is always hope, when one comes out,†said Crook. “Always.†(The Hotel Hold-Up)

This new life means new ways of thinking and behaving. In one story (Darkness), Crook became involved in trying to prevent a murder, and found himself becoming angry: “Blackguards!†he muttered, and, for a moment, almost saw red. But he stamped out his emotion, for that interfered with clear thought and intelligent action.

In another informative paragraph there is a bit more about his new attitude in this new life of fighting crime:

Detective Crook did not often allow himself relaxation. In his endeavors to wipe out a regretted past, he found it difficult to justify the gift of leisure when it came within his grasp, and he drove himself with a relentless conscience. (Death’s Grim Symbol)

The first story in the series appeared in the June 20, 1925 issue: “Red Eyeâ€. One of the regulars in the early stories was Edgar Jones, Scotland Yard detective. He worked in Crook’s household as a butler under the name William Thomas. He was certain that Crook was still a criminal, and determined to get the evidence.

It is very similar situation to the one in the Lester Leith series written by Erle Stanley Gardner, which also appeared in this same magazine later. And like that series, the employer (Crook) knows that the servant is a detective but does not let him know that.

In the first group of stories from 1925, X. Crook is still developing his reputation and proving to the police that he is really a reformed person. This came to a climax with the story “Thomas Doubts No Longerâ€. In this story some criminals and former associates of Crook give him an ultimatum, demanding that he give up trying to be honest and come back to their gang. He refuses, causing the criminals to try to frame him. He resolves that to the satisfaction of the police, who doubt him no longer. The fake butler becomes Crook’s assistant, but soon disappears from the series.

In the story “Elsie Cuts Both Waysâ€, Crook finds himself the victim of a plot by criminals to revenge themselves upon him. However, Crook is not easily fooled and the criminals wind up captured by the police and himself. Not a totally satisfying story, and it does not bother to explain on what grounds the criminals are arrested because they actually did nothing criminal.

Farjeon presents small puzzles in many of the stories, and Crook usually solves these fairly easily, though occasionally one presents a harder solution. These puzzles are not where the clues are given to the reader in the Golden Age of Detection style. Crook takes on cases of many kinds, from searching for missing persons to catching thieves and murderers. He occasionally becomes involved in crimes by accident, such as in “The Hotel Hold-upâ€. This is a very short story which shows Crook at his best, outwitting a criminal with ease. Though he is now a great believer in honesty, Crook does admire cleverness in his opponents and notes this here.

Unlike many other crime solvers of this period, Crook does not work on cases for only the well off and higher classes (for example, see the Dr. Eustace Hailey series). He will take cases from lower class shopkeepers and ordinary workers. A good example of this kind of case is “The Absconding Treasurer†(July 23, 1927), where the Christmas fund of a number of people is missing. The amount involved is less than one hundred pounds, so this shows Crook does not let this low amount influence his decision to take the case. He doesn’t mention a fee in this case, so he might have done it for a nominal or no fee at all.

He mentions in one story that he “never ate heavily when engaged on a case†(The New Baronet). There is little or no violence in most of the cases he works on, like many other stories in Flynn’s at this time. That degree of violence in the magazine gradually changed over a period of time, until by the early 1930s there was plenty of violence, like many other detective pulps.

However, to show that the Crook stories didn’t need to be violent to be effective, see the September 3, 1927 story, “The Man Who Forgotâ€. While in Dulverley on a case, Crook is sitting on a seashore bench. Another man also on the bench strikes up a conversation with Crook, revealing that he is an amnesiac. The conversation between the two, steered by Crook’s questions, gradually reveals information about the man. The two leave the bench and backtrack the amnesiac’s trail in an effort to learn the truth about him. They uncover the truth and discover a crime, but Crook’s optimism about people gives the story a kind of upbeat ending.

Some of the stories are excellent, without any of the faults noted. “The Stolen Hand Bag†in the March 19, 1927 issue, is an example. Crook overhears a restaurant conversation about a woman’s handbag theft, and shortly afterwards comes the news of the suicide of a baronet nearby. He sees a connection between the two events, and his investigation proves it.

This investigation involves Crook working with the police investigator on the case. In a number of cases, showing his standing and reputation with the police, Crook was called in or called himself in to work on a police case. Crook also worked with the police on a case of apparent suicide in “No Motive Apparentâ€, another of the better stories. In this story, it was noted:

There were police officials who, jealous of Detective Crook’s successes, declared that he was apt to be slow; but behind all his leisurely questions his brain was always acting fast, and when he had made up his mind no man could be quicker.

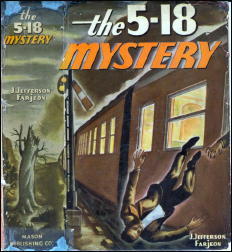

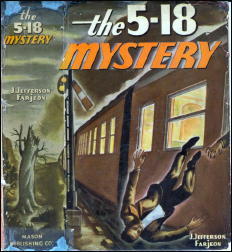

The characters and stories are nothing like Farjeon’s novels. Having read Greenmask and The 5:18 Mystery, the difference is clearly seen. The lead characters in both novels are young men who accidentally happen into mysteries, and also into romantic entanglements. They are caught up in mysterious affairs out of their control, similar to the plots of a number of Alfred Hitchcock’s movies.

Farjeon is noted in one source as “one of the first detective writers to mingle romance with crime.†This may be true of his novels, but not in the Detective X. Crook series. No romance ever creeps into Crook’s life. He seems to have come to terms with the way the world is and has devoted his life to criminology. Sounds like some of the other manhunters of the pulp era.

Other novels were not as the two described above. One of his later novels was Aunt Sunday Takes Command (1940), involving three elderly women taking a trip to visit their niece and inadvertently becoming involved in crime. A rather low-key story, unlike the other two described.

The mystery writer Dorothy Sayers considered Farjeon one of her favorite writers (Crime Time, “Reviewing The Reviewer: Dorothy L Sayers as crime critic 1933 – 1935”, by Mike Ripley). However, nowadays he seems to be a forgotten writer, and the Crook stories seem rather dated in comparison to some of his novels. Not having access to all of his books, it is not known as to whether the stories were ever gathered in collection form, though it would take more than one book to do so. However, Farjeon has quite a long list of published books so one of them may contain some of these stories.

The Detective X. Crook series by J. Jefferson Farjeon:

Red Eye June 20, 1925

The Bilton Safe June 27, 1925

The Way to Death July 4, 1925

Thomas Doubts No Longer July 11, 1925

Fisherman’s Luck July 18, 1925

Where the Treasure Is August 1, 1925

The Hidden Death August 8, 1925

Nine Hours to Live August 22, 1925

Elsie Cuts Both Ways August 29, 1925

Crook’s Code December 19, 1925

Percy the Pickpocket December 26, 1925

A Race for Life January 2, 1926

Seeing’s Believing January 9, 1926

The Deserted Inn January 23, 1926

Death’s Grim Symbol February 6, 1926

Crook Goes Back to Prison April 10, 1926

Who Killed James Fyne April 17, 1926

Caleb Comes Back April 24, 1926

The Vanished Gift May 1, 1926

The Death That Beckoned May 15, 1926

Footprints in the Snow July 17, 1926

The Shadow July 24, 1926

Cats Are Evil August 14, 1926

The Silent House August 28, 1926

The Kleptomaniac September 18, 1926

The Knife October 23, 1926

The Hotel Hold-up November 20, 1926

The Silent Client November 27, 1926

Darkness December 11, 1926

It Pays To Be Honest December 18, 1926

Kidnaped December 25, 1926

Whose Hand? January 8, 1927

The Datchett Diamond January 29, 1927

Vanishing Gems February 5, 1927

The Murder Club February 26, 1927

LQ585 March 5, 1927

The Stolen Hand Bag March 19, 1927

Prescription 93b March 26, 1927

The Thing in the Room May 7, 1927

In the Diamond Line May 28, 1927

The New Baronet June 4, 1927

The Fourth Attempt July 9, 1927

The Absconding Treasurer July 23, 1927

The Man Who Forgot September 3, 1927

No Motive Apparent September 24, 1927

The Cleverness of Crockett October 29, 1927

August 13th September 8, 1928

The Photograph September 15, 1928

Between Calais and Dover September 22, 1928

The Bloodstained Handkerchief October 6, 1928

Wanted October 13, 1928

The Third Act December 29, 1928

The Secret of the Snow February 9, 1929

Open Warfare February 16, 1929

The Photographic Touch March 9, 1929

The “Times” Advertisement March 30, 1929

The Golden Idol April 13, 1929

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

11. INSPECTOR FRAYNE, by Harold de Polo.

12. INDIAN JOHN SEATTLE, by Charles Alexander.

13. HUGO OAKES, LAWYER-DETECTIVE, by J. Lane Linklater.

14. HANIGAN & IRVING, by Roger Torrey.

15. SENOR ARNAZ DE LOBO, by Erle Stanley Gardner.