Sat 6 Oct 2012

Archived Review: ROBERT PATRICK WILMOT – Blood in Your Eye.

Posted by Steve under Bibliographies, Lists & Checklists , Characters , Reviews[13] Comments

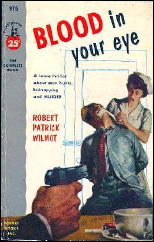

ROBERT PATRICK WILMOT – Blood in Your Eye. J. B. Lippincott, hardcover, 1952. Pocket 975; paperback, October 1953. Cover illustration by James Meese.

Blood in Your Eye is the first of three cases cracked by New York City private eye Steve Considine, and for the record, here’s a list of all three:

Blood in Your Eye. Lippincott, 1952; Pocket 975, Oct 1953.

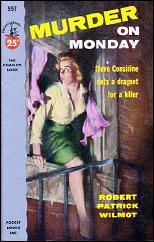

Murder on Monday. Lippincott, 1953; Pocket 997, March 1954.

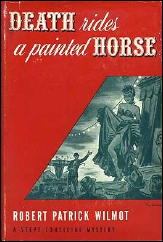

Death Rides a Painted Horse: Lippincott, 1954; Jonathan Press #80, abridged, no date.

You’re much more likely to like this one if you’re a fan of hard-boiled tough guy detective fiction; it really isn’t one that’s going to convert you. The cover of the paperback is (um) an eye-catcher, and the first 100 or so pages are terrific. By that time, though, while the pace hasn’t let up, the air has started to leak out of the tires, and by the time the book is over, you may have cause to wonder from where solution came, far left field?

To start at the beginning, though, Considine is hired to wet-nurse an actively practicing but generally amiable alcoholic on a plane trip to England, where a doctor is waiting for him. On the night before their departure, Charlie Gillespie, given in the past to hallucinatory and (hence) quite invalid misinterpretations of everyday events, claims to have seen a murder committed, and soon after, goes underground and disappears completely.

Considine’s job: find him, and thus we have a story. What I think I’ll do is give you two long quotes, both of which caught my attention in no uncertain terms, but in not exactly the same way. First, from pages 36-37, where Considine is alone in a bedroom with a girl who’s involved — and of course there is:

She bit hard and it hurt like hell and I went crazy mad, for a moment. I got my right hand into her hair and gripped it and spun her around and slapped her across the mouth with the flat of my bloody left hand. Then we were locked in tearing, panting embrace, me trying to hold her hands while she clawed at my face and jerked her knees up into my body, until I got both her arms pinned and pulled her so close that she couldn’t use her hands or knees, and I could feel her breasts swelling firm and big against my chest, and her curved long thighs against my thighs.

Desire and rage were so completely mingled within me that I twisted her wrist even as I kissed her lips — and I kissed her lips hard. Her head went back and she gave a long, sighing, panting breath, and for an instant her lips met mine wide and warm, and her body seemed to melt in a yielding movement that made it part of my own… Then she butted me solidly on the cheek with her head and twisted loose from my hands.

It’s quite a first date, even for a kindergarten teacher, which in fact she is, although Considine doesn’t know that yet. He continues:

The girl’s name is Carla Paul, and later on — here’s the other quote coming up now — Considine is talking the case over with the cop on the case. From pages 65-66:

“Sometimes,” I said, wondering what-the-hell.

“You know how it is in those stories,” Christie said. “They got a regular formula. The hero is always a bright gum-shoe, with ideas, and he’s always getting fouled up with a lot of stupid, sadistic city cops who do everything they can to prevent him from solving the crime.”

“I bet you could write yourself,” I said. “How do you know, if you haven’t ever tried?”

Christie ignored my remark. “So, because of the dumb cops, our Shamus hero has to more or less take the law into his own hands. In order to bring the villain to book, it’s necessary for our hero to break every law in the book, himself.”

“Tell me more,” I said.

“Take a case like this,” Christie went on. “The cops might wanna case Carla Paul’s room, just to see what they could see. But they’d need a warrant, because if Carla or the landlady came in while they were shaking down the place, there’d be hell to pay. If it did happen to be a case of mixed identity, I’d hate to be the cop who happened to be caught with a handful of her unmentionables.”

“Time presses,” I said, “so suppose I just take the story from here. The Shamus in your story isn’t inhibited by legal red tape or bothered by stupid principles against the search. Right?”

“Oh, so right,” Christie cooed.

“So he waits until Paul isn’t home,” I said, “and he opens her door with a skeleton key, or maybe a strip of celluloid because that makes it sound harder. He goes into the room and combs it good, and maybe he finds something — a letter or something — that gives him a line on Mr. Blair? Okay so far?”

“Perfect,” Christie answered, avoiding my eyes. “I doubt if Raymond Chandler himself could do better.”

“There’s only one thing wrong,” I said, “and that’s the possibility that someone may come in and catch the bold hero in shaking down the apartment. Someone like a big, tough policeman, for instance. Or a two hundred and fifty pound wrestler, who doubles as a janitor.”

“That ain’t in the script,” Christie said, “but I’ll admit it would be awkward if it happened.”

“Yes, wouldn’t it? And then our Shamus gets carted off to the nearest police station and placed in a backroom where a lot of uncouth persons ask impertinent questions about him having been in the apartment. And then maybe Shamus gets so indignant that he gives a discourteous answer, and loses some of his teeth.”

I flipped my cigarette at the cuspidor and grinned at Christie. “I need my teeth, lieutenant. I might be sent out on a job that paid so well I could afford to eat steak.”

Christie rolled a pencil around on the desk top and looked at me thoughtfully. “Of course,” he said, “the Shamus could always ask to speak to Lieutenant Christie.”

“No doubt he could,” I said, “and by the time he got to talk to Christie, our hero would have a pocket full of teeth. See you later, Chris.”

We went out, and as we closed the door, Christie sighed again.

I don’t know about you, but for me, that was worth the price of admission, right there. I also have to admit that there was a time, about half way through, that I had absolutely no idea where the story was going next, and that’s doesn’t happen, or at least not very often.

You may take that as a good thing — I do — but what it also means it that it takes a full final chapter that’s ten pages long, after the bad guys have been named and identified, to tie up all of the loose ends, or at least all but one, a huge, massive coincidence that Wilmot dares not even mention, but I will. Possible? Sure, but without it, it all falls apart.

[UPDATE] 10-06-12. I’ve not been able to find any personal information about the author online, but I did come across a reference to one quote that’s interesting. From the cover or jacket flap of a British edition of Death Rides a Paper Horse: “Robert Patrick Wilmot has been compared by Anthony Boucher of the New York Times to the young Dashiell Hammett.” I have not found the quote from the Times itself, but it does suggest that reading the book again may be in order, or even all three of them.