THE SERIES CHARACTERS FROM

DETECTIVE FICTION WEEKLY

by Monte Herridge

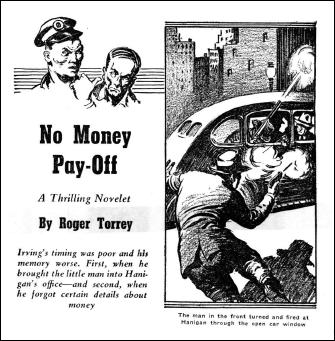

#14. HANIGAN & IRVING, by Roger Torrey.

The Hanigan & Irving stories by Roger Torrey were a short series of eleven stories published in Detective Fiction Weekly from 1937 to 1941. There are two main characters in the series and a number of supporting ones. The main characters are private detective Michael “Mickey†Hanigan and his assistant – Irving Koslowski the taxi driver.

Hanigan is a former cop, probably a detective, before he opened up his agency. “Hanigan had ethics, though of a peculiar sort and often discounted by the police department.†(Suicide Story) Irving usually drives a decrepit old taxi and takes Hanigan wherever he needs to go and also assists when needed. Irving’s last name was Borowski in “The Meter Says Murder†but changes to Koslowski later in the series. (see “Murder Tips the Scales†from 1940)

Supporting characters include Nancy Evans, Hanigan’s girl friend, always ready to try to convince Hanigan to take the day off and relax. But Hanigan usually resists the temptation, insisting that he needs to be in his office in case someone needs him. She tried to help him in the first story in the series, but wound up making a mess of matters, so she refrains from helping him after that unless he asks her.

Various police detectives are also supporting characters in the stories, but they are different in each story.

Irving is introduced in the first story in the series, “Case for a Killer†(DFW, September 17, 1937), and is of assistance to Hanigan in the story. Hanigan just picks his taxi at random, and does not identify Irving by name in his first scene. In a later scene, after Hanigan repeatedly calls him Jack, Irving corrects him and tells him his name.

He also tells Hanigan: “You’re the kind of a guy I like; one that makes up his mind.†Before the two go to a Greek bar, Hanigan tells Irving: “To this Greek spot, and you’re to go in with me. If there’s any dough in this, I’ll see you’re taken care of. If not, you got a steady customer at least.†So it was by sheer accident that the two met up and Irving became hired by Hanigan for future jobs.

In another story (The Meter Says Murder) Hanigan defends his hiring of Irving: “Now about Irving. The guy ain’t making any money hacking and all I’ve got to pay him is enough for him to get along. And the cab’s handy and he’s a handy boy.†Later Hanigan seems to regret his hiring of Irving, for it was said about him: “Irving Kowalski, who drove a taxi part time and who drove Hanigan to desperation practically the remainder of the time. . .†(Suicide Story)

Irving’s description was given in “Suicide Storyâ€: “Irving wasn’t tall but he was built like a Shetland pony. Stocky. There’d been several times when he hadn’t ducked in the right direction and these errors in judgment had given him a slightly lumpy appearance. One ear had been torn and this hung at a slight angle, and the gold teeth he’d chosen to replace originals knocked out by knuckles, shone at Hanigan out of the murk.â€

In the first story in the series, “Case for a Killerâ€, the story is longer than later stories. It is described as a short novel, and the other stories in the series are novelettes. Hanigan is hired to bodyguard Nick Poulas and his young daughter for four days until they sail on a ship for overseas.

Unfortunately, an assassin breaks into the hotel room while Poulas is giving his story to Hanigan and shoots Poulas with a shotgun. Hanigan takes this hard, and promptly shots the assassin while he is trying to escape. He hides the daughter from the police and goes out on an investigation. Poulas had a valuable briefcase that is missing, so Hanigan searches for that too.

There is a big conflict between the police and Hanigan and Irving on one side, and two group of crooks on the other. Irving did a good job helping, and the police captain said about him: “Well, he’s a bearcat.†Hanigan replied: “He’s my boy. He’s going to work for me.†So that incident tied up the connection between Hanigan and Irving.

In the second story, “The Meter Says Murderâ€, Hanigan is in trouble over a murder. He had had an argument with a newspaper journalist, whom he threatened. The journalist shows up dead the next day in Irving’s taxicab, and both Hanigan and Irving wind up down at the police station trying to explain the situation to one of the Homicide detectives. Hanigan then sets out to investigate the case and clear his name.

“You Only Hang Once†starts off with Hanigan being called upon to bail Irving out of jail. Irving has a number of charges against him, which he says he is not guilty of committing. The person putting the charges against Irving winds up murdered the next day, and Hanigan gets involved when an heir to a hefty sum is accused of the crime.

Irving is attacked and both stabbed and slugged, and Hanigan is also attacked when he finds a seriously injured Irving in his taxi. It doesn’t take long for Hanigan to clear up the cases, which are all connected, once he gets a bit of cooperation from friends in the police department.

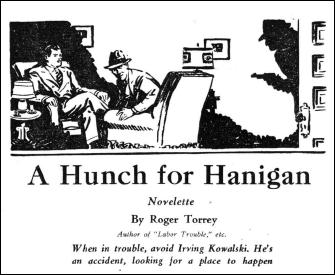

“A Hunch for Hanigan†finds Hanigan searching for and finding a missing heiress. The case becomes complicated when the heiress is mysteriously killed in an automobile accident with a train. Both the police (in the person of Detective-Lieutenant Simpson) and Hanigan find the accident suspicious.

The woman’s husband, who happens to be the number one suspect in the death, asks Hanigan to investigate the crime and find the murderer. In this story, Hanigan works well with Detective-Lieutenant Simpson.

“Suicide Story†starts off quickly, with a woman entering Hanigan’s detective agency office and attempting to shoot him. He disarms her and has her tell him why she shot at him. Her boyfriend committed suicide, she said, because Hanigan was investigating his firm.

Hanigan promises to look into the matter and goes to the seedy hotel where the man had been staying. What he finds convinces him that it is murder, not suicide, and he decides to check further into the case.

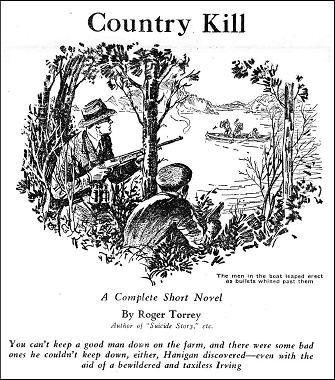

In “Country Kill†Hanigan is called to the country for a case by a landowner who is being sniped by an unseen rifleman. The shooter doesn’t seem to want to hit anyone, just cause a nuisance. His client is an unpopular person in the neighborhood, making matters more difficult.

The case becomes more complicated when not only is a murder committed, but also three city gunmen decide to come to the area supposedly for fishing on the local lake. Hanigan calls Irving to come down to help him, and leave his taxi behind. Irving doesn’t like being separated from his taxi.

“A Bodyguard for Beano†starts off with Hanigan being hired to bodyguard the rich owner’s prize pedigreed English bulldog, and then moves on the real motive for the hiring. Joseph T. Collins, the dog owner, has really hired Hanigan to bodyguard him. He is in fear of his life from his other three partners in his business firm.

One attempt on his life took place on the first day Hanigan arrived at Collins’ house and before Collins told him why he was there.

“No Money Payoff†starts with Irving bringing in a tipster to Hanigan’s office. The tipster claims he knows about a jewelry theft worth ninety thousand dollars that the insurance company would pay to know about. Hanigan, with a hangover from the night before, doesn’t believe him and throws the guy out.

Irving is convinced the guy is telling the truth, and follows him, only to run into the middle of the kidnapping of the tipster by two crooks. Irving is shot, and winds up in the hospital. He tells Hanigan the story, and Hanigan finds out there actually was a jewelry heist that the tipster could know about. Then he is interested in tracking down the tipster and finding the jewels in order to get the insurance company fee.

This is probably the most violent of the stories in the series. Five men are killed (one a policeman) and two are seriously hurt. Only Hanigan’s good detective instincts and experience keep him safe from harm.

In “Murder Tips the Scales†Hanigan and Irving become involved in a plot to kill some ex-politicians. The first politician asks for Hanigan’s help but is killed before Hanigan can do anything or find out any more information than a threatening note stating that three will be killed.

As usual, Irving convoys Hanigan around in his taxi, but he does get in on some of the action. Irving chases a suspect in a scene, but somewhat ineptly. He buys another taxi, but it keeps breaking down and stranding Hanigan and Irving. The murderer turns out to be the least likely suspect.

Police Detective-Lieutenant George Woods was ready to give Hanigan a hard time about virtually anything to do with his current cases. Woods often thought that Hanigan knew some facts about his current criminal case. And Woods was right; Hanigan just didn’t want to tell Woods anything because he was working on the case. Hanigan was in it for the money.

“Frame for a Killer†opens with Hanigan and Irving unknowingly being framed for a jewelry robbery and murder in the same building that Hanigan’s new was located in. Most of the story consists of Hanigan and Irving trying to get out of the frame and get the right criminals.

First Hanigan has to escape from two policemen who have arrested both him and Irving for the crimes. A shootout with the criminals finalizes the case. Then Hanigan has to explain matters to the police, who don’t look too kindly on Hanigan for assaulting their detectives.

This is an above average series, with some good stories. There is an element of humor in the stories, often contributed by Irving’s actions. Irving is actually of some assistance in Hanigan’s cases, even with the humorous situations.

This series deserves to be reprinted. The stories are fairly long, so eleven stories might fill a book.

The Hanigan & Irving series, by Roger Torrey:

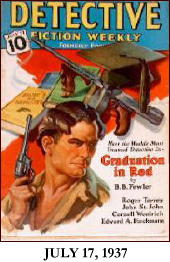

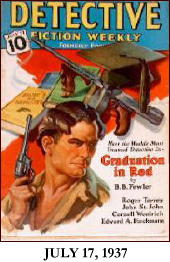

Case for a Killer July 17, 1937

The Meter Says Murder December 11, 1937

You Only Hang Once April 23, 1938

Labor Trouble September 17, 1938

A Hunch for Hanigan November 12, 1938

Suicide Story April 15, 1939

Country Kill May 27, 1939

A Bodyguard for Beano August 26, 1939

No Money Payoff December 16, 1939

Murder Tips the Scales February 24, 1940

Frame for a Killer November 1, 1941

Previously in this series:

1. SHAMUS MAGUIRE, by Stanley Day.

2. HAPPY McGONIGLE, by Paul Allenby.

3. ARTY BEELE, by Ruth & Alexander Wilson.

4. COLIN HAIG, by H. Bedford-Jones.

5. SECRET AGENT GEORGE DEVRITE, by Tom Curry.

6. BATTLE McKIM, by Edward Parrish Ware.

7. TUG NORTON by Edward Parrish Ware.

8. CANDID JONES by Richard Sale.

9. THE PATENT LEATHER KID, by Erle Stanley Gardner.

10. OSCAR VAN DUYVEN & PIERRE LEMASSE, by Robert Brennan.

11. INSPECTOR FRAYNE, by Harold de Polo.

12. INDIAN JOHN SEATTLE, by Charles Alexander.

13. HUGO OAKES, LAWYER-DETECTIVE, by J. Lane Linklater.