FIRST YOU READ, THEN YOU WRITE

by Francis M. Nevins

Perhaps I’ve written a bit much lately about Lawrence Block. Perhaps it’s time to return to another of this column’s favorite subjects, classic Golden Age detective fiction. Are you with me?

***

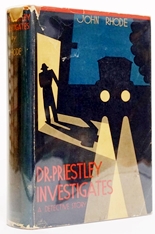

I’ve been reading John Rhode off-and-on since I was a teen, and found that his pre-WWII Dr. Priestley novels were far superior to those that postdate the War. I’ve rarely read one as early as PINEHURST (1930; US title DR. PRIESTLEY INVESTIGATES), one of the early novels in the long-running series. Unlike the later entries, this one offers substantially fewer characters, and that professorial old curmudgeon has a bigger and more active role than he assumes in his postwar outings.

We open on a rainy foggy November night as young Tom Awdrey, much the worse for liquor, drives erratically into the port city of Lenhaven and is stopped by two constables, who haul him into the police station and book him on a drunk driving charge, only to find a dead body, apparently run over by Awdrey’s car, in the dickey (what we’d the call the rumbleseat) of his two-seater. As chance would have it, Superintendent King is at the station chatting with an old friend, Chief Inspector Hanslet of Scotland Yard, who sits in on the next morning’s interrogation.

Awdrey denies the existence of a body in his car and insists that what was in the dickey was a bust, a plaster cast of a sculpture called “The Slave-Trader†which he was bringing to its creator, a well-known sculptor who spends winters in Lenhaven. That cast is nowhere to be found. Awdrey also claims that he picked up a passenger not far from the town and dropped him off at a gate near an out-of-the-way pub called The Smelters’ Arms.

Hanslet visits the pub and learns from the landlord that the gate leads to Pinehurst, a huge and all-but-ruined old house presently owned by a strange old man named Coningsworth who lives there in total isolation with his wife and daughter and sister-in-law and a gardener, a yacht of sorts anchored nearby in the mud of the River Drew and connected with land by a gangway.

Coningsworth apparently spends his evenings prowling around the grounds with a rifle, and on one occasion started shooting unaccountably into the darkness. His daughter tells Superintendent King that someone had fired shots into the house a few nights earlier while the family were at dinner, and the gardener reveals that someone had dug a huge hole in the kitchen garden’s lily-of-the-valley bed. On Hanslet’s return to London he visits Dr. Priestley and gives him an account of the case. Priestley theorizes that there’s something valuable hidden in or around Pinehurst, and that somebody is after it.

A few days later he and his secretary Harold Merefield revisit Lenhaven, which the Professor had first seen in an earlier Rhode novel, THE HOUSE ON TOLLARD RIDGE (1929). That night there’s a burglary at Pinehurst with nothing taken but a hundredweight of brass door-fittings and nothing left behind but some fingerprints that prove the criminal is missing the middle finger of his right hand. Investigating Coningsworth’s bedroom, Priestley and King find a huge assortment of firearms and what seems to be a homemade burglar alarm.

Eventually, and thanks to Priestley’s acumen, the sleuths learn that before Coningsworth was run over he was poisoned by something called convalleramin which I suspect Rhode made up out of (dare I say it?) whole cloth. Late in the proceedings a roughneck sailor takes center stage and tells the investigators the backstory, which involves the hijacking of rum-running vessels off the Atlantic coast. Prohibition, remember, was still in force in the U.S. at the time.

PINEHURST is not without its flaws: the double life of one of the main characters takes a bit of believing, and Rhode for no earthly reason reveals the identity of the murderer in THE HOUSE ON TOLLARD RIDGE. On the plus side, although Priestley freely admits that he has “nothing tangible with which to support†some of his numerous deductions, most of them strike me as better grounded and less speculative than a lot of his conclusions in other novels. That virtue, together with a climax featuring more physical action than we’re accustomed to see in Dr. Priestley novels and some vivid descriptions of the area, lead me to recommend this one as somewhat above average for Rhode.

***

Does the name E. C. R. Lorac ring a bell? The U.S. publisher of the earliest novels to appear under that byline referred to the author as Mr. Lorac but in fact “he†was a woman, Edith Caroline Rivett (1894-1958), who wrote 48 detective novels as Lorac and another 23 as Carol Carnac. Seven of the early Loracs were published on this side of the pond by Macaulay but most of her novels didn’t come out over here until after World War II when as both Lorac and Carnac she became a fixture in the Doubleday Crime Club stable.

Her best-known series character was Scotland Yard sleuth Robert Macdonald, who figures in every one of the four dozen Loracs but, as far as I can tell, is not characterized at all beyond the fact that he’s a Scot. In the entry on Rivett in 20th CENTURY CRIME AND MYSTERY WRITERS (3rd edition 1991), Mary Ann Grochowski describes Macdonald as “physically active, lean, tall, with a penchant for walking the English countryside though a most expert driver when the occasion demands one.â€

THE CASE OF COLONEL MARCHAND (1933) was her fifth novel published in England and third in the U.S., two of the first quintet having never made it across the Atlantic. Detective Chief Inspector Macdonald is called in to investigate the poisoning murder of a wealthy 55-year-old womanizer and patron of the arts while having tea in his elegant Grosvenor Square drawing room with a lovely young lady, identity unknown, who apparently walked out of the house with her music case and some valuable jewelry after her host dropped dead.

Everyone else in the house at the time of the poisoning worked for Marchand—his secretary Richard Lambert, the lordly butler Gibbs, the racing-buff chauffeur Fenton, the young footman Dicks—and all of them except a couple of anonymous menials seem to be concealing something. When the remains of the tea and of the cakes and sandwiches that were served with it are found innocent of poison, and when the substance that killed Marchand is identified as potassium cyanide, which is a solid not a liquid, Macdonald broadens the circle of suspects to include people who weren’t in the colonel’s house at the time of his death, particularly his solicitor John Dillon and his nephew Derrick.

A few days after the murder the mystery woman comes forward and reveals that Marchand was, as we say nowadays, hitting on her, and claims that when she walked out he was alive and well. Macdonald drives her back to her home, a studio in Gower Street mainly inhabited by artistic types, and sees leaving the building none other than Marchand’s nephew, a clear indication that he knows either the young woman or one of the other tenants. Investigating these, he discovers—although Lorac doesn’t tell us this immediately—that one of the others, not an artist but an analytical chemist, is the spitting image of the dead colonel’s nephew. The mystification builds to an action climax in the burial ground of an old London church.

I haven’t read enough Lorac to rank MARCHAND among the Macdonald novels but, thanks not only to the plot but to the echoes of World War I and the Depression and the details of painting and sculpture and music and interior decoration, it did sustain my interest throughout. The murderer however is the most stereotypical culprit imaginable, and the clue that leads Macdonald to the poisoner strikes me as an extremely slender reed on which to build a structure of incrimination. Barzun and Taylor in A CATALOGUE OF CRIME (2nd edition 1989) have nothing to say about this one but tell us that only two of Rivett’s novels are “first-quality performances†and then name only one of them, MURDER BY MATCHLIGHT (1946), which I happen to have. Maybe it’s worth a look.

***

Did anyone guess? After these excursions we return to perhaps the least likely suspect when it comes to Golden Age detective novels. Yes, Lawrence Block again. And for good reason.

There were no more Matthew Scudder novels for three years after A LONG LINE OF DEAD MEN but in his next appearance he might almost have been a different character. Few if any would use the word noir to describe EVEN THE WICKED (1997), in which Block abandons the sense of existential menace and the laser focus on suffering and death to try his hand at something closer to, believe it or not, our old amigo the Golden Age detective novel, complete with references to those masters of the locked room John Dickson Carr and Edward D. Hoch. One character even calls Scudder Monsieur Poirot!

The major storyline involves someone signing himself The People’s Will who has taken to writing letters to a New York Daily News columnist, predicting and then bringing about the violent death of various evildoers. First to be killed is a rapist and murderer of children whom, along with his female accomplice, Scudder describes as “animals—a label we affix, curiously enough, to those members of our own species who behave in a manner unimaginable in many of the lower animals.†The woman had the decency to kill herself; the man, like a certain infamous murder defendant about two years before this novel’s publication, was acquitted thanks to having a fictional counterpart of Johnnie Cockroach as his lawyer.

Next to bite the dust is a Mafia kingpin “who had survived innumerable attempts to put him behind bars,†followed by an anti-abortion fanatic whose rhetoric was responsible for a clinic bombing and the assassination of a doctor and nurse. The subject of the fourth death prediction is a violent Jew-hating black radical, although Will (as he’s come to be known) is saved from following through on this prophecy when his target is beheaded with a ceremonial ax inside his walled compound by one of his entourage.

Then comes a fifth letter, targeting the lawyer who got the child-murderer acquitted, and this (pardon the expression) man calls in Scudder, who arranges round-the-clock protection for him with the large agency he occasionally does per diem work for. Despite a phalanx of bodyguards and a Kevlar vest, the attorney is killed anyway, in his luxury apartment, by cyanide added to a bottle of single-malt whiskey under impossible circumstances. (This accounts for the references to Carr and Hoch.)

In due course Scudder figures out the truth behind all five deaths but there’s a problem, not for him but for his creator: as of this point the book is nowhere near long enough. Block deals with the problem by involving Scudder with another murder, this one occurring before the locked-room poisoning, its victim a former drug addict visibly dying of AIDS with which he was infected by needle-sharing but shot to death in the vest-pocket park across the street from his Greenwich Village apartment by a killer who took pains to verify his victim’s identity before pulling the trigger.

This crime doesn’t fit Will’s MO but arguably was a sort of practice run by the serial killer. After learning a great deal about life insurance (did you know murder is considered an accidental death, triggering a policy’s double indemnity clause?) and the so-called viatical arrangements that were common when AIDS was rampant and fatal, Scudder cracks this case too, encountering that utter rara avis in Block, a somewhat sympathetic murderer.

But the book still isn’t long enough, which is why at the beginning of Chapter 18 a second Will pops up, mailing new threats to the same tabloid columnist the first Will corresponded with. This aspect of the novel is then suspended until the beginning of Chapter 24 when Scudder returns from Ohio, having cleaned up the viatical case, and learns that there’s been a new victim, a vicious New York Times theater critic. (Anyone remember John Simon?)

Scudder solves this murder too, pulling off what is known in hockey as the hat trick. But what a difference from earlier books in the same series! EVEN THE WICKED is so cerebral it’s hard to believe it’s a Scudder novel, and so disunified one could almost believe Block shoehorned into the works two short stories, unrelated to each other or to the main plot, in order to wind up with 328 pages. I suspect he was trying his damndest to escape from what for all its intensity had become something of a formula for him, but I for one wish he’d stayed closer to home and so, I believe, do many of his readers.