Wed 28 Oct 2015

A Halloween Movie Review by David Vineyard: BLOODSUCKERS (1970).

Posted by Steve under Horror movies , Reviews[3] Comments

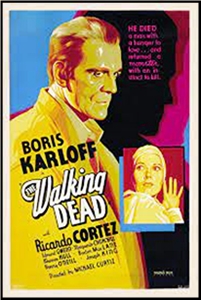

BLOODSUCKERS. Titan Film Distribution Ltd., UK, 1970, as Incense for the Damned. Chevron Pictures, US, 1971. Patrick MacNee, Peter Cushing, Alexander Davion, Patrick Mower, Johnny Sekka, Madeline Hinde, Edward Woodward, and Imogen Hassall as Chriseis. Screenplay by Julian Hoare, based on the novel Doctors Wear Scarlet by Simon Raven. Directed by Robert Hartford-Davis as Michael Burrowes.

Before you get excited about that cast and the bona fides of this film know going in, it is, by any definition, a bomb.

Brilliant Oxford don Richard Fountain (Patrick Mower) is missing in Greece, upsetting his friends back at Oxford including the man who expects him to fill his chair, Peter Cushing. Tony Seymour (Alexander Davion), a fellow friend and former student has arrived asked by the Foreign Office to look into Fountain’s case since there are hints of some trouble in Greece. Along with Penelope (Madeline Hinde) Richard’s fiance and friend and student Bob (Johnny Sekka) Seymour sets out for Greece where he enlists Major Longbow (Patrick MacNee) in the search.

It soon turns out Fountain has gotten in with a fast and nasty set, in particular a silent beauty named Chriseis (Imogen Hinde) and there are a string of bodies in their wake — victims of a vampire. His friends rescue Fountain and return him to England but after consulting an expert on vampire cults (Edward Woodward) realize too late that Fountain himself is infected.

This troubled film was rejected by everyone involved with it, not the least Simon Raven, the brilliant gadfly of low behavior among the upperclasses who wrote the novel it was based on. Raven, best known for the Alms for Oblivion and First Born of Egypt sequences of novels (and a co-author credit on one of the Bond films) following a group of less than noble nobility and upper class types across British society in the post war 20th Century, often wrote borderline genre fiction including the thriller Brother Cain, and the mystery novel Feathers of Death. Doctors Wear Scarlet (the title refers to the robes worn by those at Oxford with a doctorate), a psychosexual vampire novel, was his most successful blend of his subject and genre fiction, a genuine classic among admirers of vampire fiction (chosen one of the 100 Best), and well worth reading for lovers of the form.

Raven’s brand of razor wit, bitchiness, suggested perversion (and actual perversion), the ruthless immorality of the upperclasses, suspense, intrigue, low humor, and gossip is never even suggested here, the best the film manages being a vague suggestion of bi-sexuality which at least was true to the novel. What Raven’s novels brilliantly serve cold and bitter this film doles out in overheated attempts at perversion that, for all the nudity, look like a Mid-Western high school drama class attempt at a production of Tennessee Williams’ Suddenly Last Summer.

Cushing and MacNee do the best they can with guest star roles, but you have to wonder if MacNee was relieved mid-picture when his character plunges to his death at the end of the Greek segment. Woodward has the ungrateful role of explaining Raven’s very sexual take on vampirism (a metaphor for sex to begin with, or at least venereal disease in Stoker) in some attempt to bring reason to this mess of a film.

The title has it half right. This film sucks.