REVIEWED BY MICHAEL SHONK:

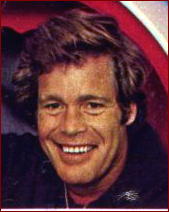

SEARCH. NBC, 1972-73. Leslie Stevens Production in association with Warner Brothers Television. Created and Executive Produced by Leslie Stevens. Cast: Doug McClure as C.R. Grover, Burgess Meredith as V.C. Cameron.

This is the last of four posts examining the TV series SEARCH and its pilot TV Movie PROBE. For earlier posts:

Probe [Pilot/TV Movie]: https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=16030

Search [The Hugh O’Brian episodes]: https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=20990

Search [The Tony Franciosa episodes]: https://mysteryfile.com/blog/?p=21076

Of the featured three Probe agents C.R. (Christopher Robin) Grover’s role was the least defined, but it didn’t start out that way. According to Leslie Stevens, originally Grover was to be the stand-by Probe, unassigned to any unit. He would have been a bit of a goof-off, someone motivated only by a pretty girl. He also would have been an incredible Probe agent, tough, brilliant, eager to solve the case and get back to goofing off.

You can see some of that Grover in his first episode, “Short Circuit,” but that Grover was quickly gone.

The key to Grover became his youth. He was impulsive, unconventional, had a sense of humor, fallible and insecure from a lack of experience. He was respectful to Cameron and women. Doug McClure was able to take these characteristic and make Grover the most likable character of the series.

Sadly, the writers failed to take advantage of McClure’s portrayal in a positive way. Stories and locations should have been aimed to appeal to the younger audience. There were few opportunities for Grover to romance the girl of the week, more often the women were married or committed to another man, and even when there was a girl of the week the scripts did not spend enough time exploring the romantic possibilities.

Without having a purpose such as belonging to a Probe unit, Grover’s cases were generic, dealing with cases that didn’t fit Lockwood or Bianco or worse, were leftovers. For example, the episode “Numbered For Death” where Grover attempts to convince Probe to take a case to help old friends, a married couple. It involved a mobster and blackmail. All of that was more fitting for Nick Bianco than young Grover.

EPISODE INDEX —

Produced by Robert H. Justman. Probe Control Cast (recurring): Ron Castro as Carlos, Ginny Golden as Keach, Byron Chung as Kuroda, Albert Popwell as Griffin, Amy Farrell as Murdock, Tony DeCosta as Ramos, and Mary Cross as June Wilson.

“Short Circuit” (9/27/72) Written by Leslie Stevens Directed by Allen Reisner. Guest Cast: Marianne Mobley, Jeff Corey and Nate Esformes *** One of the scientists that created Probe’s technology has gone mad and threatens to destroy Probe Control with a new devices that causes feedback in electronic systems until they explode.

Logic was not this episodes strong point, but it was entertaining enough. A rare case when Grover gets the girl at the end. Hugh Lockwood would have approved.

“In Search of Midas” (11/8/72) Written by John Christopher Strong and Michael R. Stein. Directed by Nicholas Colasanto. Guest Cast: Barbara Feldon, Logan Ramsey and George Gaynes *** Probe is hired to find out if a reclusive billionaire is still alive. Joining Grover on the case is a female gossip columnist, who is one of the few who knows what the billionaire looks like.

What a mess of a script. Too many characters overwhelmed the Howard Hughes plot. Some scenes were padded while others needed more setting up to work. The romance was neglected and twists were wasted.

“A Honeymoon to Kill.” (1/10/73) Written by S.S. Schweitzer. Directed by Russ Mayberry. Guest Cast: Luciana Paluzzi, Antoinette Bower and George Coulouris *** Heiress is about to inherit a trust that would give her control over her “dying” father’s business that specializes in making military weapons. After her wedding, she is shot at and runs off alone. Her husband hires Probe to find her.

Good action episode with non-stop chases, fights, and twists. McClure and Luciana Paluzzi made the story more watchable than it deserved.

“The Packagers” (4/11/73) Written by Robert C. Dennis. Directed by Michael Caffey. Guest Cast: Xenia Gratsos, Michael Pataki, and John Holland *** After being exiled to Paris with the Country President’s daughter, a failed revolutionary goes missing, Probe is hired to find him.

Typical 70’s TV low budget portrayal of a revolution with the twists obvious, the believability nil and Grover at his most bumbling. Final episode of the series to air.

As prior posts have stated, there was a change in showrunners. Two episodes left over from Stevens as showrunner (red Probe Control), one with Lockwood (Hugh O’Brian) “Suffer My Child” and the other with Grover (“The Packagers”) aired after the eight Spinner produced episodes (blue Probe Control) aired. Spinner produced three Grover episodes.

Produced by Anthony Spinner. Probe Control Cast: Pamela Jones as Miss James and Tom Hallick as Harris.

“Numbered For Death” (1/31/73) Teleplay by S.S. Schiweitzer. Story by Lou Shaw and S.S. Schiweitzer. Directed by Allen Reisner. Guest Cast: Peter Mark Richman, Bert Convy and Luther Adler *** Someone had gotten the numbers to secret Swiss banking accounts and using them for blackmail.

Production values had collapsed with Probe Control looking like it was operating out of World Securities’ break room. The acting was bad, Bert Convy with an alleged English accent bad. The lack of mystery also hurt, but the overly simple way the blackmailer got the information ruined the episode.

“Goddess of Destruction.” (2/21/73) Written by Irv Pearlberg. Directed by Jerry Jameson. Guest Cast: Anjanette Comer, Alfred Ryder and John Vernon *** A murder of a dealer of ancient Indian art may signal the return of the ancient cult of assassins, the Thugs.

The story was mildly entertaining but contains no surprises. Budget cuts show the outdoors of Bombay looking so much like Los Angeles you want to chip in to help the producers buy some stock footage. Probe Control was becoming less and less involved to the point where Burgess Meredith got out from behind his desk to visit the art gallery and client.

“Moment of Madness.” (3/14/73) Written by Richard Landau. Directed by George McCowan. Guest Cast: Patrick O’Neal and Brooke Bundy *** Cameron is kidnapped from Probe Control. Searching for Cameron, Grover realizes how little he knows about him.

Cameron was working nights giving taped orders to various agents around the world. One must wonder if business had gotten so bad Probe laid off the night shift, after all its day somewhere in the world. Seriously, if you have an actor of Burgess Meredith’s talent you need to focus on his character in at least one episode.

Having Cameron snatched from Probe Control, the top secret headquarters for World Securities was just one of three Spinner produced episodes that portrayed World Securities as a bungling inept organization (the others were Spinner produced Hugh O’Brian’s “Countdown To Panic” where World Securities bungled a scientific experience and exposed the world to a killer virus, and Tony Franciosa’s “The 24-Carat Hit” when Probe agents screwed up and a field agent’s wife was killed and daughter kidnapped.)

A man who had served in the Korean War under the command of Government Intelligence Officer Captain V.C. Cameron blamed Cameron for his capture by the enemy. Now he sought revenge by forcing Cameron to endure the same torture he did as a POW.

Grover’s search for Cameron lead him to V.C.’s only surviving family, a niece.

What made this episode worth watching were the talents of Burgess Meredith and Doug McClure.

In my last post I looked at the ratings and how the audience rejected the series, so how did the critics feel? Here are some excerpts from reviews of the first episode (“Broadcasting” 9/25/72).

“It’s a gimmick show and a series can go only so far on a gimmick. Last night it went about two inches.” (Howard Rosenberg, Louisville (KY) Times)

“Unquestionably, there is a lot to say for SEARCH, like contrived, ludicrous, gimmick, and dull.” (Don Page, Los Angeles Times)

“The plots demand more reality, the characters should be less cartoony.”(Morton Moss, Los Angeles Herald-Examiner)

Leslie Stevens’ SEARCH, with the teaming of man and his sidekick technology, tried to recreate the charm of such series as THE MAN FROM U.N.C.L.E. and THE AVENGERS. If he had developed better characters popular enough to overcome the lack of plausibility in the plots and solutions he might have succeed.

Anthony Spinner’s SEARCH stripped the charm from the series and turned it into just another MANNIX with corporate security inept and Probe Control reduced to a minor supporting role for the almighty individual agent. Yet Spinner’s SEARCH might have found an audience if NBC had moved it to a different time slot away from CANNON.

As I remember, SEARCH was a great series, fun and entertaining, but memories are selective. My fondest memory was the character Gloria Harding (Angel Tompkins) who was in two of the twenty-three episodes, and I remembered nothing of Nick Bianco, C.R. Grover or any of the Spinner episodes.

Returning to the past can be a slap of reality. I found SEARCH a watchable show, at times fun and entertaining and at times the opposite, just like much of television then and today.

RECOMMENDED READING:

TV Obscurities: http://www.tvobscurities.com/articles/search

Rap Sheet: http://therapsheet.blogspot.com/4009/06/search-me.html

Warner Bros Press Releases: http://probecontrol.artshost.com/publicity.html