WINDY CITY PULP CONVENTION 2021 REPORT

by Walker Martin

A group of about five collectors have been making this trip out to Chicago for over 10 years but this year only three of us made the two day drive out to the convention. One of our group could not make it due to pandemic restrictions and one hurt his back moving bookcases just prior to the show. This injury was especially sad since he always looks forward to the pulp shows and has been attending them since the second Pulpcon in 1973.

We had nice weather driving to and from the show and enjoyed several meals together, especially the ones at the Outback and Longhorn Steak House. The three of us discussed several topics during the drive, including memories of past Pulpcons and my adventures at the first one in 1972, a mere 50 years ago. Somehow it feels like only the other day that I drove out to St Louis and discovered so many great friends and great pulps.

In fact we often hear about people entering their second childhood if they live long enough, and the same rule applies to pulp and book collectors. For instance back in the 1980’s I got rid of my almost complete set of G-8 and His Battle Aces and here I am 40 years later buying a complete set of the 110 issues again. I imagine I will dislike Nippy and Bull just as much as I did decades ago, but I also love the great insane covers just like I did so long ago. Thanks Doug. Just what I needed, another set of G-8 to complain about.

What else did I buy? I have an almost complete set of Sea Stories, over 112 issues and I’ve always wanted an original cover painting. Thanks to Doug (again!) I bought the painting for the cover of the June 20, 1923 issue. True, this is not a great one like the ones Anton Otto Fischer painted, but then again I probably cannot afford such great art anyway.

I’ve been buying paperback cover art by Larry Schwinger for over 30 years, starting in 1989 with two Cornell Woolrich covers. This convention I bought another one, a real bargain at only $100. But my old pal Scott Hartshorn beat me to another bargain by Schwinger, the cover to Hombre by Elmore Leonard. I tried to immediately buy it from Scott, but he’s so greedy that he refused my offer.

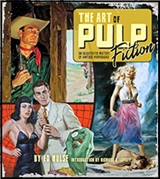

I also bought some books including 3 volumes of the R.A. Lafferty collections presently being published by Centipede Press. They plan to publish 12 volumes but the print runs are only 300 each, so they go out of print fast and are expensive to find. Speaking of books, Ed Hulse had an advance copy of his new history of vintage paperbacks. Go to the Murania Press website to order. The book has over 450 paperback covers in color and will be shipping starting September 28. The title is The Art of Pulp Fiction: An Illustrated History of Vintage Paperbacks.

There were some paintings I wanted to buy but I talked myself out of buying them because I have no space and I don’t want to add to the stacks of art leaning against the walls and bookcases, a common problem that collectors face as they accumulate art. Fred Taraba had a great Frontier Stories cover painting from 1925 and Craig Poole had a McCauley from Amazing Stories but I manage to escape the show without adding to the stacks of art.

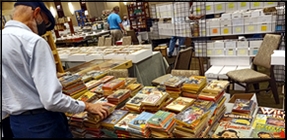

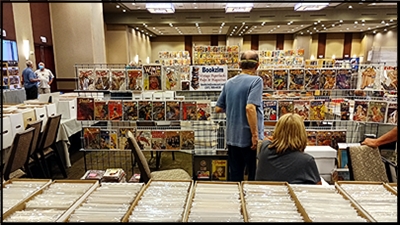

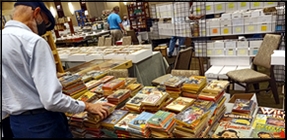

During the old days of Pulpcon in the 1970’s, 1980’s and 1990’s, there were often what we called “feeding frenzies”, where the entire dealer’s room seems to swarm around certain tables with rare and desirable pulps. This no longer happens that often but it did at this Windy City show. Andrew Zimmerli had several tables crammed with hundreds of rare old pulps.

To give you an example of what happened, Matt Moring missed the first day of the feeding frenzy but still managed to find around 50 old Adventure’s that he needs, mainly from the hard to get teens. He now only needs 40 or 50 issues to complete the set of 753 pulp issues, 1910-1953. Non-collectors may not understand this but believe me it is a major achievement.

Doug Ellis mentioned to me that attendance was 500 and there were 168 tables. Despite the pandemic, these are excellent numbers. Masks were required, maid service limited and restaurant hours limited. The auction was the main event for Friday and Saturday evening. In the old days’, Rusty Hevelin believed the comic book dealers should by banned from Pulpcon, but we live in The Brave New World today and so the comic book influence was evident. For instance the so called “bat girl” cover of Weird Tales sold for $11,000 and there were conversations about “slabbing” pulps.

This is the future where we will see rare and expensive pulps slabbed like many comics in plastic. Readers Beware!! I guess we will have to change the old saying, “So many books, so little time” to “So many books, but since they are enclosed in plastic, we have plenty of time”. The “slabbers” say only the expensive books will be slabbed and there will be reprints to read but to me slabbing books is still sacrilege. I get it about slabbing baseball cards but pulps and books?

The auction also included over 300 lots of other Weird Tales, rare pulps, Robert Howard items, and correspondence, including some great letters from Farnsworth Wright, the editor of Weird Tales. Most of the items were from the estates of Robert Weinberg and Glenn Lord.

There were two panels. The Friday night panel discussed upcoming books by Edgar Rice Burroughs and the Saturday night panel discussed the magazine, Black Mask. I talked about how I managed to complete a set of the 340 issues back in the 1970’s and fellow panelists also discussed the Joseph Shaw era and the Ken White years of 1940-1948. The other three collectors on the panel were long time collectors John Wooley, Will Murray, and Matt Moring. We had to be tough and hard boiled to talk about such a subject in only 45 minutes!

There was the usual art show and films. This year Ed Hulse ran the films only during the day and not at night or after the auction. As usual Sunday was New Pulp Sunday with panels discussing the subject. The 20th edition of Windy City Pulp Stories was excellent and all 158 pages dealt with Black Mask and Dashiell Hammett. This is a must buy if you have any interest in pulps or Hammett.

The next Windy City Pulp show will be May 6, 2022 through May 8, 2022. Same hotel and hosted as usual by Doug Ellis and John Gunnison. Thank you for your efforts. I know a lot of work went into this convention. Thanks too to Paul Herman and Matt Moring for allowing me the use of the photos they took for this report. I hope everyone survives the plague and that we all meet again next year!