Fri 7 May 2021

A Book! Movie!! Movie!!! Review by Dan Stumpf: W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM – The Narrow Corner // Film (1933) // ISLE OF FURY (1936).

Posted by Steve under Films: Drama/Romance , Reviews[6] Comments

â— W. SOMERSET MAUGHAM – The Narrow Corner. William Heinemann Ltd., UK, hardcover, 1932.

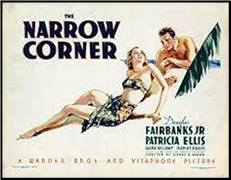

â— THE NARROW CORNER. Warners, 1933. Douglas Fairbanks Jr, Patricia Ellis, Ralph Bellamy, Dudley Digges, Artur Hohl, Reginald Owen, Willie Fung, and Sidney Toler. Screenplay by Robert Presnell. Directed by Alfred E. Green.

â— ISLE OF FURY. Warners, 1936. Humphrey Bogart, Margaret Lindsay, Donald Woods, E.E. Clive, Paul Graetz, George Regas, Tetsu Komai, Miki Morita, and Frank Lackteen. Screenplay by Robert Hardy Andrews and William Jacobs. Directed by Frank McDonald.

The Narrow Corner finds Maugham striding confidently through Joseph Conrad territory, with a Marlow-like narrator recalling his encounter with a young wastrel out cruising the south seas to evade a murder rap in Australia. With the ship laid up for repairs on a remote island, the young man meets a family of simple, decent Dutch traders and finds love (or does he?) when it’s too late (or is it?)

Maugham does a splendid job with the locations, the simple plot and the complex characterizations, but it sometimes seems he’s trying too hard to write a Serious Novel when he could be telling a Good Story. I should also add, in case you’re bothered by it, that this is the homosexiest straight novel I’ve seen in some time: the women are generally predatory or self-absorbed, and Maugham spends a lot of time contrasting the physical beauty and innocence of the young men with the saggy, baggy dissipation of their elders.

Despite the subtext, The Narrow Corner was snapped up by Warners and filmed just a year after publication. In those heady, pre-code days, Hollywood could still exploit the steamy exoticism of the thing, and director Alfred E. Green and writer Robert Presnell did rather well by it, Presnell excising Maugham’s pretensions, and Green slapping the story on screen with pace and style.

Corner offers one of the best storm-at-sea scenes ever in the Movies, plus a cast of able thespians (including Doug Fairbanks Jr. as the wastrel, Patricia Ellis as the love-starved island girl, Dudley Digges and Arthur Hohl as dope-addict doctor and crooked captain, and Sidney Toler as a tough “fixer.â€) delivering some sharp lines. The film falls down only in the casting of Ralph Bellamy, the mere appearance of whom gives away the ending immediately.

A few years later, Warners went to the well again, and to their credit, they made an enjoyable “B†picture out of the thing. True, they tossed out most of Maugham’s novel (He got screen credit anyway, which he may or may not have welcomed.) but they filled it up with crackerjack ideas of their own invention: shifty natives planning robbery and fomenting unrest; a larcenous skipper prone to murder; undersea mayhem, and even a hokey octopus!

Humphrey Bogart, sporting an unflattering mustache, stars as a husband balanced precariously on the edge of cuckoldry when mysterious castaway Donald Woods turns up on his remote tropical island. Wise old Doctor E.E. Clive is quick to intuit the attraction between Woods and Bogey’s bride (lovely Margaret Lindsay, whose star burned steadily in Hollywood but somehow never caught fire) but writers Andrews and Jacobs cut away to the action scenes before things get too syrupy.

They also do a good job of fleshing out the characters to more than B-movie dimensions. Director McDonald lets his actors expand to fit the parts, as his camera moves gracefully through the studio tropics. As for Bogart, well, this was the point in his career when Warners was still wondering what to do with him, the years he spent playing second-leads, vampires and Mexican bandits. He looks a bit as if at any moment the writers might decide to kill off his character, and the uncertainty works well in this context. It’s not Maugham’s novel, but it’s a dandy bit of entertainment in the Warners style.