Sat 5 Sep 2020

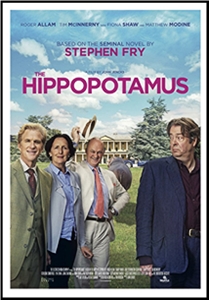

A Movie Review by David Vineyard: THE HIPPOPOTAMUS (2017).

Posted by Steve under Films: Comedy/Musicals[18] Comments

THE HIPPOPOTAMUS. Lightyear Entertainment, 2017. Roger Allam, Mathew Modine, Fiona Shaw, Tim McInnerny, Emily Berrington, Geraldine Sommerville, John Standing, Tommy Knight, Dean Ridge. Screenplay by Blanche McIntyre, Tom Hodgson, John Finnemore, & Robin Hill, based on the novel by Stephen Fry. Directed by John Jencks. Available on DVD, as well as streaming on Amazon Prime.

To begin with, Ted Wallace (Roger Allam) has committed original sin, he’s a poet, worse still he’s a successful published poet even though it has been five years since the wrote a line. These days he makes his living at an even worse crime: he “commits journalism.†He is a theatrical critic.

At least he is until he blows up during a particularly odious production and is escorted out by the police after having sucker punched the director.

Ted is miserable and self destructive, and now he is broke as well, but Ted is about to be thrown a lifeline by an unlikely source, his goddaughter Jane (Emily Berrington) who is dying of cancer and recently in remission.

Jane is convinced she has been saved by a miracle, the nature of which she will not reveal, but wishes Ted to investigate, at her Uncle, Lord John Logan (Mathew Modine)’s estate (“he did something unspeakable for Margaret Thatcher†to earn his knighthood, we are told).

Ted is more than willing for the 25,000 Sterling offered, but things are a bit strained between him and his old school chum John, but then things are a bit constrained between him and Jane’s Mother, John’s sister (Geraldine Sommevile) too. In fact things are a bit strained between Ted and the world, but if he is just careful he can get by claiming to be concerned about his nephew young David (Tommy Knight) who is sensitive, awkward, and wants to be a poet.

Those are just some of the odd things about David, as Ted will soon learn, because though there isn’t a corpse or a murder in sight, The Hippopotamus (Ted) is a manor house mystery in the mode of Agatha Christie replete with eccentric characters, carefully hidden family secrets, and a reluctant but acerbic and quite able sleuth in Ted himself.

John Logan once saw his father save a man’s life, and he has believed his father had a gift all his life. Now he thinks it skipped a generation and is in his son David, who it seems has performed three actual miracles, starting my saving his mother’s life. John wants to protect David from being exploited, but is also a bit too in awe of that supposed gift.

Just how David performed most of those miracles though is among the more hilarious and scandalous things about this tale.

Most of the laughs here are of the quiet variety, but real enough. Despite the constant flow of acid and obscenity from Ted, the film is gentle as very nearly as everyone involved, but Ted has a desperate need to believe in a miracle that ultimately will do more harm than good. He is an unlikely hero, but before it is over he and several others will be saved, though not without cost.

There is even a delightful great detective moment when kicking the bucket puts all the pieces of the puzzle together.

Suspects include Tim McInnerny as a flamboyant homosexual who lives on the estate; Fiona Shaw as David’s protective, and sane, Mother; a house guest and her plain daughter who pose another threat to David; Jane’s mother who still loathes Ted after their breakup; and Simon (Dean Ridge) David’s sane nice brother.

John Standing has a nice bit as Podmore, the aging and rather bored butler.

All in all, it builds up to a satisfying conclusion with Ted even getting to play at Hercule Poirot at a gathering of the suspects when he puts the pieces of the puzzle in the right order that everyone else has jumbled up in their own needs and hopes. As in a Christie novel everyone sees the same things, but only Ted sees them as they are and not as everyone would like them to be.

The novel is by Stephen Fry, himself an acerbic actor, comic, and commentator who has appeared in numerous movies, television shows (a semi regular role on Bones), was teamed with actor Hugh Laurie as Jeeves to Laurie’s Wooster and in a variety series, and who has written several novels, one a modern version of The Count of Monte Cristo. Fry is one of those jack of all literary and artistic trades that seem to appear when needed in British entertainment and enrich us all.

It is almost impossible to describe anything from Fry without the words, wicked, delicious, delightful, playful, sinful, arch, amusing, intelligent, or barbed, and that perfectly sums up this bright tale where the laying on of hands becomes a different kind of miracle in the mind of an oversexed teen than you would ever expect.

Feel the need to escape, but to do so without sacrificing brain cells, then this is perfect for you. Literate, well played, vicious and kind at the same time, arch and human, nasty and heartfelt, it is a delight as novel or film. There is a definite Ealing comedy feel to it, with a touch of Oscar Wilde, the zing of Monty Python, and just enough black humor (or at least dark gray) to leaven the whole thing.

We are in those delightful British waters where dwelt Oscar Wilde, John Mortimer, P. G. Wodehouse, Kingsley Amis, Simon Raven, Iris Murdoch, George Orwell, Timothy Findlay, and in a comic mood Graham Greene, and it is refreshing indeed.