Sun 26 Apr 2020

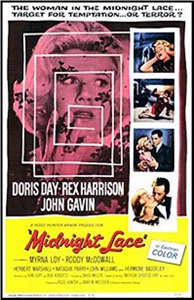

A Movie Review by David Friend: MIDNIGHT LACE (1960).

Posted by Steve under Reviews , Suspense & espionage films[4] Comments

MIDNIGHT LACE. Universal Pictures, 1960. Doris Day, Rex Harrison, John Gavin, Myrna Loy, Roddy McDowall, Herbert Marshall, Natasha Parry, Hermione Baddeley, John Williams, Anthony Dawson. Director: David Miller

Kit Preston (Doris Day) is an American heiress, living with her financier husband Tony (Rex Harrison) in affluent Grosvenor Square. Three months into their marriage, all seems well, but during a night-time walk alone through the foggy London streets, Kit hears a high, ghostly voice which, as well as knowing her name, threatens to kill her. Kit escapes, though her story is received light-heartedly by Tony, who believes a merciless practical joker is behind the incident. Next day, an accident at a construction site nearly kills Kit, and she is saved by good-looking contractor Brian Younger (John Gavin), who also, somehow, knows her name. Things get even more sinister when Kit receives a mysterious telephone call and is terrorised anew by the voice – now vowing to kill her by the end of the month.

At the behest of Kit’s friend and neighbour Peggy (Natasha Parry), Tony takes Kit to Scotland Yard. Inspector Byrnes (John Williams) suspects Kit may be lying in order to receive attention from her busy husband. Kit continues to be terrorised by phone calls and remains on edge whenever she ventures outside. On one such occasion, she again encounters Brian, who reveals he used to suffer blackouts during the war. Kit is later menaced by a scarred man at home (Anthony Dawson), but nobody believes her.

Even Tony thinks she is delusional, particularly when a doctor suggests Kit may be suffering from a split personality and arranging the calls herself. Tony is already distracted by work – an embezzler is stealing funds from his company – but decides to take Kit on holiday to Venice after she breaks down in despair. The caller, though, rings again and promises to kill her that evening. Tony and Kit plan a trap, one that quickly gets out of hand…

Think Doris Day, and most people will think of romantic-comedies like Pillow Talk and That Touch of Mink, the musicals Calamity Jane and Young at Heart, and ‘Que Sera Sera’. But, of course, that song came from Hitch’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, which sometimes seems to be forgotten when considering Day’s catalogue. Perhaps because it was emphatically a Hitchcock film, with no less a titan than James Stewart in the main role, but it at least proved she could perform persuasively in another genre. She did it again, sandwiched between two Rock Hudson pairings, in 1960’s Midnight Lace. Coincidentally, or not, this psychological thriller pulls plenty from the Hitchcock playbook. In fact, it was hard for me to think of it as anything else. Aside from Day, it features three other actors who had been cast by Hitchcock in other films – Anthony Dawson and John Williams from Dial M for Murder, and almost-Bond John Gavin from Psycho.

All of whom are reliably good whatever they are in, and though Dawson has far less to do here, he remains an ominous presence throughout, skulking enigmatically in doorways and giving Day – and us – the shivers. John Williams, happily, is playing more or less the same role as he did six years earlier, remaining every bit the quintessential Scotland Yard detective. Midnight Lace has other similarities too, being set in London and revolving around a wealthy blonde woman, married to a dark-haired Englishman named Tony, while her life is in danger. Grace Kelly, of course, had no warnings, while here Day is given almost nothing else. Relentlessly menaced, and disbelieved by everyone she knows, Kit begins to lose her sanity – something which the audience may already be questioning too.

The films charts this descent, but in broad strokes, making the whole thing seem more like the grim, foreboding Suspicion rather than a psychoanalytical study like Spellbound. Obviously, it also evokes Gaslight, though this is a little less sinister as Kit never truly believes she is mad. The film would today be described as domestic noir.

Though I like this name, it does rather ignore the fact that the genre stretches back at least to the eighteenth century gothic fictions which Jane Austen partially parodied with Northanger Abbey, then onwards into the romantic suspense novels of Mary Stewart, Victoria Holt and V. C. Andrews. The heroines in such things, however, were more independent than Kit is here. She doesn’t investigate the situation, merely suffers it, while a man comes to her aid at the end. There’s a short scene at the opera where she is politely assertive to a creepy, though thankfully furless, Roddy McDowall, and it would have been nice to see her demonstrate such steel elsewhere. Were it remade today, its star would almost certainly demand more fight from the character, though perhaps that would remove the elements of danger and helplessness which otherwise defines this gripping, atmospheric thriller. Highly recommended.

Rating: *****