Mon 11 Jan 2016

Music I’m Listening To: JENNIFER TRYNIN “Better Than Nothing.”

Posted by Steve under Music I'm Listening ToNo Comments

From this Boston-based rock singer’s 1994 CD, Cockamamie:

Mon 11 Jan 2016

From this Boston-based rock singer’s 1994 CD, Cockamamie:

Sun 10 Jan 2016

THE LONE WOLF RETURNS. Columbia Pictures, 1935. Melvyn Douglas, Gail Patrick, Tala Birel, Henry Mollinson, Thurston Hall, Douglas Dumbrille, Raymond Walburn Screenplay Joseph Krumgold, Lionel Houser, Bruce Manning. Characters created by Louis Joseph Vance. Directed by Roy William Neill.

ARSENE LUPIN RETURNS. MGM, 1938. Melvyn Douglas, Virginia Bruce, Warren William, John Halliday, Nat Pendleton, Monty Woolley, E. E. Clive, George Zucco, Vladimir Skoloff, Ian Wolfe, Tully Marshall. Screenplay by Howard Emmett Rogers, James Kevin McGuinness, George Harmon Coxe based on their story. Character created by Maurice Leblanc. Directed by George Fitzmaurice. (*)

You can be forgiven if these two films leave you more than a bit confused when it comes to gentleman cracksmen since both films feature perpetual second lead, Melvyn Douglas as the questionably reformed title hero making yet another foray into crime and detection. In The Lone Wolf Returns he is reformed jewel thief Michael Lanyard, a Parisian-born American jewel thief who famously changed his ways for the love of a woman. The back story for his adventures dated to the silent era where actors like Jack Holt played him, and indeed this 1936 outing is a remake of the 1926 film.

The plot is simple here; Lanyard, retired in America, is lured out of retirement by a fabulous emerald owned by Gail Patrick while under the watchful and distrustful eye of Inspector Crane (Thurston Hall, who would remain a regular in that role in the Warren Williams Lone Wolf series that followed). Lanyard, easily the most easily unreformed and re-reformed crook in fiction, toys with taking the jewel, falls for the girl, and then falls afoul of a gang determined to use his skills to get the jewel for themselves. He isn’t called the Lone Wolf for nothing though, and he manages to foil the gang, rescue himself and the girl, and stay semi reformed, at least until the next film in the series.

The Lone Wolf was the creation of Louis Joseph Vance, a popular American novelist whose work appeared in the early pulps and slicks of his day. He had a number of bestsellers, often as not works of romance, adventure, and crime, and continued the adventures of Michael Lanyard until his death adding a son and daughter of the Lone Wolf along the way.

The Lone Wolf not only added a phrase to popular fiction with his name, he also managed to keep going through silent film, radio, talkies, and a syndicated television series, starring former film Saint, Louis Hayward, in which Lanyard had reformed enough to work as an insurance investigator — not that anyone was ever completely convinced of his reform, including Lanyard who had an eye for a shapely karat as well as an ankle.

This well done outing features fine direction by Roy William Neill and a simple straightforward script that benefits from Douglas’s droll underplaying of the reformed crook. Even he never really seems sure until the last minute whether he is going to steal the jewel or not, and that helps.

Despite the title The Lone Wolf Returns was the first of a new series and not a sequel, whereas Arsene Lupin Returns is a sequel to the 1934 film Arsene Lupin, which starred John Barrymore in the title role versus Inspector Ganimard in the person of Lionel Barrymore (one of only a handful of films they worked together in) and Karen Morley a shapely police agent.

Whether a series was contemplated (another Lupin film Enter Arsene Lupin was made in 1944 with Charles Korvin), the notable cast of the first film was kept in mind and this time the brilliant Lupin is up against canny ex-FBI agent turned private detective, Steve Emerson (Warren William, shortly to be Michael Lanyard the Lone Wolf and himself a screen Perry Mason to confuse things more) in a Parisian adventure, though you would never know it by the accents.

Emerson may be no match for Lupin, but he is far from the lunk-headed tecs usually pitted against the hero, enough so you could easily pull for him. His chief drawbacks are his assistant Nat Pendleton, and the authorities like Prefect of Police George Zucco and Monty Woolley who insist Arsene Lupin is dead and gone, lo these many years.

Again there is a fabulous emerald, this time the property of Baron de Grissac (John Halliday) and adorning the bosom of the baron’s beautiful daughter Loraine (Virginia Bruce). Lupin is around as retired gentleman Rene Farrand, who Emerson suspects is far more than a bored gentleman farmer and indeed the notorious Arsene Lupin, and when an attempt is made on the jewel it begins to look as if Lupin is up to his old games.

Created by French journalist Maurice Leblanc, Arsene Lupin had an even grander career than the Lone Wolf, with his adventures appearing in just about every form of media from newspaper serials to animated cartoons to this day. While he is not as well known as he once was in this country (he was President Theodore Roosevelt’s favorite detective), in the rest of the world he as been featured in countless reprints, pastiche (continued by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narjeac of Diabolique and Vertigo fame), film, television series, comic books, manga, animation (including the adventures of his grandson Lupin III in Japanese manga and anime as well as live action film), a 2004 film, and even a television series from the Philippines loosely based on his adventures.

There is even a stylish animated series available on DVD and YouTube done in recent years known as Night Mask or Arsene Lupin. Most episodes of the stylish live action French television series from the 1970‘s can be watched on YouTube in French or sets purchased on line.

Like most gentleman adventurers Lupin eventually becomes as much a crime solver as criminal, but unlike Michael Lanyard he never really makes much effort to reform. He enjoys being Arsene Lupin and thumbing his nose at police and crooks, rescuing ladies in distress, and distressing anyone who deserves it. He is the most unrepentant criminal in all fiction who still manages to be a good guy and not an antihero.

Sad to say, for all its good qualities, Arsene Lupin Returns largely wastes Halliday, Zucco, and Woolley (in all fairness, it was an early role and they didn’t quite know what to do with Woolley yet). There isn’t a lot of suspense, Lupin will get the girl, save the jewel, and Emerson will take his defeat like a gentleman wishing Lupin, his rival for the girl, merrily on his way. The greatest pleasure is watching Douglas matched against William, a bit fairer battle than usual in this sort of film, though not as fair as a better script might have had it.

Truth is, American film and media didn’t quite know how to handle Lupin. He isn’t deprived or depraved, he has no long sad story to tell, he chose to become a criminal because it was a good way to make money and have fun, and while he isn’t above avenging the wronged or pursuing evil he’s not really a Robin Hood. He goes to considerable length over his career to acquire the treasures of the Kings of France, and not for the public good. He is also very French, and his combination of ego, arrogance, and Gallic brio can be a bit hard on American audiences brought up on phlegmatic American and British heroes.

Arsene Lupin Returns avoids that side of his personality, but because it does he is never quite Lupin, just as no one and nothing in the film is quite French.

Still, you really should see both of these if possible. They are well done pictures with attractive casts and better than average performances, scripts, and direction. Douglas has considerable charm as does William, and both films are good examples of a kind of film Hollywood used to make effortlessly. If The Lone Wolf Returns is the slightly better picture, it is also the slightly less interesting one of the two. They really should be seen in tandem to appreciate them, though.

(*) I thought it worth noting both films had an actual mystery writer working on the screenplay. Bruce Manning co-wrote mysteries with his wife Gwen Bristow, and of course George Harmon Coxe who worked on Arsene Lupin Returns, was one of the Black Mask Boys creator of Flash Casey and Kent Murdock.

Sun 10 Jan 2016

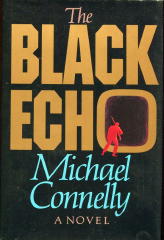

MICHAEL CONNELLY – The Black Echo. Hieronymous Bosch #1. Little Brown, hardcover, 1992. St.Martin’s, paperback, July 1993. Reprinted many times since.

This is Connelly’s first novel, and if it has any value as a predictor I think we have some good books to look forward to. According to the publicity, he is at work on the second novel featuring Harry Bosch. Bosch is an ex-“star” LAPD homicide detective, more or less in exile and disgrace after shooting an unarmed man. He is a Vietnam vet, an ex-tunnel rat, and has been an outsider and a loner all his life.

As the book opens he is called to a homicide involving a murdered man in a long pipe around the reservoir, a tunnel, if you will. The victim turns out to be another ’Nam tunnel rat, with whom had Harry served. Harry still alternates between nightmares and insomnia from his war experiences, and this doesn’t bode well for his future peace of mind.

As the case develops, the murdered man appears to have been involved in a major robbery in which the city’s sewer system was used to tunnel into a bank vault As Harry pursues this, he discovers that the FBI had suspected the dead man, and indeed know about Harry as well. Rather than acceding to his request for cooperation, they try to use pressure within the LAPP to force him off the case.

When this fails, he is assigned to work with one of the FBI agents, Eleanor Wish, full time. Do I reveal too much by saying that there is a mutual attraction? The plot becomes very complex, with links back to Vietnam and possible corruption within the law enforcement agencies. The ending may or may not surprise you.

This is not really a cop novel, though it is about cops and has many procedural aspects. Indeed, it is almost anti-cop in that aside from Bosch and Wish, nearly all of the law enforcement agents are not attractively portrayed at all. It is as much as anything else a book about some of the things that war does to people; and, of course, it is a book about Harry Bosch.

Connelly writes very effectively, with a lean narrative style that moves the story along but still leaves room for adequate characterization. As in most books, characters other than the main few are merely sketched in, but Bosch himself is well-drawn. I didn’t like the culmination of the plot. I just didn’t believe that things would have realistically happened that way, with those people; not quite deus ex machina, but something similar.

I thoroughly enjoyed the book until the end, and even then was not sorry I had read it. I think Connelly has a bright future, and look forward to seeing more of Harry Bosch. Recommended.

Sat 9 Jan 2016

In French classical tragedy, a major “don’t” is the intrusion of the supernatural. One of classical tragedy’s less elevated offspring, the puzzle detective story, has kept to that tradition and it has always seemed to me that readers of detective fiction, in general, abhor a mixture of the “real” and the ghostly.

However, I must confess that I am perhaps inordinately fond of a dash of the supernatural in a film or tale of detection and/or mystery. I don’t require that the spooks be dispelled by a rational explanation and I’m happy even if the threat is fake spookery as long as it keeps me in a state of shivery suspense for an hour or so.

One of my favorite varieties of this kind of fiction/film is that of the menacing house in the country where a faceless (i.e., masked) horror keeps popping out of secret passageways and stretching out a fearsome claw from a panel over the heroine’s bed. I think I can trace my affinity to two sources: the thirties serials The Green Archer and The Iron Claw and a delightfully wacky 1939 version of the archetypical example of the genre, The Cat and the Canary, starring Bob Hope and Paulette Goddard (Paramount, 1939).

Forty some years later, I remember with unabated delight the scary confrontation of hero and villain in a cobweb-bedecked passage. I haven’t seen it since then and perhaps it is just as well. I might be disappointed and, at my age, such disappointments can provide graceless coups de grace to pleasurable childhood memories.

I did see, on television, the 1981 version directed by Hadley Metzger. The cast was decent (Wendy Hiller, Edward Fox, Wilfrid Hyde-White and Honor Blackman, among others) but the spooky old house was clean as a whistle, and no spider ever survived long enough on that pristine set to spin an atmospheric web or two in a dark corner (of which there were also depressingly few to be glimpsed). Atmosphere is crucial in this kind of film and the scrubbed-up, glossy technicolor versions just won’t do.

(I might add that I have never seen the highly regarded silent version directed by Paul Lent and am glad to know that this particular pleasure lies in wait for me.)

TO BE CONTINUED…

Sat 9 Jan 2016

This is the title track from bluegrass singer Claire Lynch’s 1995 CD from Rounder Records:

Fri 8 Jan 2016

ENEMY OF WOMEN. Monogram, 1944. Re-released as The Mad Lover. Wolfgang Zilzner (as Paul Andor), Claudia Drake, Donald Woods, H. B. Warner, Ralph Morgan, Gloria Stuart, Robert Barra, Byron Foulger. Written and directed by Alfred Zeisler.

A real oddity.

An independent production picked up and distributed by Monogram, this was written and directed by Alfred Zeisler, who was born in Chicago but rose to prominence in the German film industry of the 1920s and 30s, with memorable hits like Gold (1934) and Viktor und Viktoria (1933) on his resume. Like many other talents, he was forced out of Germany with the rise of the Nazis and ended up back in America, where he worked mostly on “B†products like this story of the rise and (anticipated) fall of Paul Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s Minister of Propaganda and brief successor.

Given that background, one would expect a strident film here, but Enemy is surprisingly restrained, even gentle at times. It doesn’t try to make Goebbels sympathetic or even likable, and yet ….

Goebbels is played by Wolfgang Zilzner, an actor usually cast as a sinister Nazi underling in films like Invisible Agent and All Through the Night; the guy standing behind Peter Lorre, with a sullen look and no lines. But here he’s the star, and the film opens on him, with a smooth night-time tracking shot in the rubble of a recently-bombed Berlin neighborhood (tellingly evoked by photographer John Alton, one of the architects of film noir.) Goebbels’ car arrives on the scene and he enters one of the smoldering ruins, preparing a radio broadcast to the effect that the damage was “negligible†but there’s something strange about his manner, and as he slumps into what’s left of a chair, we flash back ….

What follows is a rather staid account of the fortunes of Joseph Goebbels, starting off with him as a tutor spurned by his young student (Claudia Drake, the woman no one remembers in Detour) and hooking up with the rising Nazi Party more to recover his self-esteem than from any political conviction.

There are some understated (and economical) vignettes as Goebbels takes power and publishers and broadcasters find themselves out of work or under arrest, usually done in a single scene on one set—an approach that heightens the sense of ruthless Nazi efficiency and saves money at the same time—and a surprisingly lavish bit at a swanky party used by Goebbels to push more propaganda.

There’s also an unexpected and quite suspenseful sequence where he finds himself scheduled for a visit from the SS and has to get next to Hitler before he can be spirited away by his rivals. It’s one of those moments like the car-sinking scene in Psycho where the viewer finds himself suddenly identifying with a killer.

In fact, as Enemy of Women goes on, it becomes less about the Nazis and more about Goebbels’ ruthless pursuit of the woman he loves (the Claudia Drake character) a pursuit punctuated by murder, kidnapping and detention, but with none of the gloating villains or noble martyrs so common in movies those days.

The conclusion is skillfully and intentionally tipped off ahead of time as we suddenly recognize the room where Claudia Drake awaits her unwanted lover and this becomes, of all things, a story of losing the thing one loves by trying to possess it. The flashback ends as the master propagandist of the Third Reich delivers his prepared lies, and his close-up reveals the face of a man who realizes he is the herald of a fallen angel.

No, there are no brave patriots here, no stirring speeches or beastly villains, but despite the trashy title, Enemy of Women hits its target by humanizing it.

Fri 8 Jan 2016

FRANK GRUBER – Swing Low, Swing Dead. Belmont L92-586, paperback original, April 1964. Cover art: Victor Kalin. Reprinted several times, including Belmont B75-2039, 1970.

Once again through no fault of their own, Johnny Fletcher, masterly and maybe masterful bookseller who specializes in one title, and Sam Cragg, the strongest man in the world, are living hazardously. Sam has won all rights to a rock-and-roll song called “Apple Taffy,” the first line of which is “I love apple taffy, sweet, sweet, sticky sticky apple taffy.”

Johnny claims this song is better than most, and adds: “The whole point and purpose of rock and roll music is to see how childish, how infantile you can make it.”

Several people are seeking the original manuscript, some for a consideration, others for nothing, except, perhaps, the lives of Johnny and Sam. After all, someone has poisoned the original composer, and that someone is not likely to let a few more lives stand in his or her way.

Fletcher has street smarts and Cragg has no smarts. Both of them would like to be rich, but Fletcher knows such a change in fortune would take all the fun out of their lives, such as it is, though Cragg may have a different opinion since he likes to eat regularly. Gruber`s Fletcher and Cragg novels are great fun if not sampled too often.

The Johnny Fletcher & Sam Cragg series —

The French Key. Farrar 1940.

The Laughing Fox. Farrar 1940.

The Hungry Dog. Farrar 1941.

The Navy Colt. Farrar 1941.

The Talking Clock. Farrar 1941.

The Gift Horse. Farrar 1942.

The Mighty Blockhead. Farrar 1942.

The Silver Tombstone. Farrar 1945.

The Honest Dealer. Rinehart 1947.

The Whispering Master. Rinehart 1947.

The Scarlet Feather. Rinehart 1948.

The Leather Duke. Rinehart 1949.

The Limping Goose. Rinehart 1954.

Swing Low Swing Dead. Belmont 1964.

Thu 7 Jan 2016

HALF A SINNER. Universal Pictures, 1940. Heather Angel, John King, Constance Collier, Walter Catlett, Clem Bevans, Henry Brandon. Based on a story by Dalton Trumbo. Director: Al Christie.

What a pleasure it is to start watching a movie you know nothing about, only to discover that against all expectations you’re enjoying yourself immensely. And when that happens it’s also sometimes difficult to put into words what magic of movie-making it was that made a small visual treat as Half a Sinner such a pleasant way to spend on hour, or at 59 minutes, just a hair less.

The players themselves were not stars then, nor did they ever become stars.. Heather Angel may be best remembered, at least in some circles, as Bulldog Drummond’s girl friend Phyllis Clavering in several of the former’s movie adventures, while John King is remembered in some quarters as Ace Drummond in the 1936 13-chapter serial (no relation, I don’t imagine). He was perhaps even better known as John “Dusty” King in a host of early 40s B-westerns.

In any case, they certainly make a fine pair together in this definitely screwball mystery comedy in which Heather Angel plays a prim and proper schoolteacher who decides to kick up her heels one day, buy a nice dress and new hat, add some silk stockings and have some fun for a while.

What she doesn’t expect is to end up stealing a car (trying to escape a wolf who’s really a small time gangster) that has (she discovers later) a corpse in the back seat. As she’s making a getaway, she’s flagged down by John King’s character, who decides to play along with her as the two of them try to elude both the police and the gang of crooks who stole the car in the first place.

Of course the plot doesn’t make any sense, and the crooks are about as ineffectual as a gang of crooks could ever have been, but everybody in the fast-paced flim-flam of a movie plays it with all the gusto they’ve got. And it shows.

Thu 7 Jan 2016

JAMES SHEEHAN – The Law of Second Chances. St. Martin’s Press, hardcover, March 2008; paperback, September 2009.

This book has been sitting in a stack next to my bed ever since I bought it, over six years ago. This week I finally got my money’s worth from it. While it’s not a knock-your-socks-off kind of novel, it does have some good moments, and once started, it kept me up last night well beyond my usual bedtime.

I didn’t realize it when I began, but it turns out that this is the second book about Florida attorney Jack Tobin, the first being The Mayor of Lexington Avenue (2005). There since has since been a third, The Lawyer’s Lawyer (2013).

His story is one awfully common in fiction, perhaps not so in real life. He had once been a very successful civil trial attorney, but having pocketed a twenty million dollar buyout after one case, he’s changed his way of living around, as of course we all would. What he does now, though, is work on behalf of clients who have been unjustly accused or convicted and would like a second chance to prove themselves, hence the title.

This is a lengthy book, over 400 pages long and is made up of two separate cases, two that somewhat overlap, but they’re really quite different. In the first half of the book, Tobin finds himself negotiating a new trial for a convict who’s been on Death Row for seventeen years. The second half has him defending a (very) small time hoodlum who is charged with murder, with eye witnesses to prove it. Bennie is also the estranged son of a friend of Tobin’s, back in high school days in New York City.

Sheehan writes in a flat but engaging style that gets the job done. He’s particularly effective when it comes to matters relating to Tobin’s personal life, including flashbacks to his boyhood in New York City. But Sheehan knows his law, too, and that’s what kept me reading far into the night last night. On the minus side, I think the stakes grow far too high in the second matter at hand, nor did I ever think that [SPOILER ALERT!] Tobin’s affair with a new girl friend was anything but far too soon.

Wed 6 Jan 2016

THE DOOLINS OF OKLAHOMA. Columbia Pictures, 1949. Randolph Scott, George Macready, Louise Allbritton, John Ireland, Virginia Huston, Charles Kemper, Noah Beery Jr., Dona Drake , Robert Barrat, Lee Patrick. Director: Gordon Douglas.

Suffice it to say, there’s nothing new under the Western skies in The Doolins of Oklahoma. Starring Randolph Scott as real life outlaw Bill Doolin, this docudrama/Western has its moments, but is an overall average movie that begins and ends pretty much as you would expect it to.

What makes it worth a look, particularly for those with fond memories of this type of movie that they certainly don’t make anymore, is the presence of co-star George Macready as the U.S. Marshal on Doolin’s trail. Character actors John Ireland and Noah Beery (Jr.) feature prominently as members of Doolin’s gang. Scott, not yet the star of films directed by Andre De Toth and Budd Boetticher, portrays Doolin as a man who wants nothing more than to leave his criminal past behind him and start a new life working the land as a farmer.

Problem is: Scott’s Doolin is just too darn nice. One can hardly imagine him as a bank robber or the leader of The Wild Bunch, let alone a killer. As far as Doolin’s wife, as portrayed in the film by Virginia Huston, she hasn’t a clue. She’s nice and pretty, but that’s about as far as it goes. Still, if you happen to like Scott as a Western star – and I very much do – he’s not all bad here and does his best with the rather mediocre script.

There’s some dry humor, genuine pathos, and wit here, all delivered in Scott’s distinguished Southern gentleman’s accent. It’s just not enough to make this movie particularly memorable.